漢德百科全書 | 汉德百科全书

Turkey

Turkey

Die türkische Sprache – auch Türkeitürkisch oder Osmanisch-Türkisch[1] – ist eine agglutinierende Sprache und gehört zum oghusischen Zweig der Turksprachen. Als meistgesprochene Turksprache ist sie die Amtssprache in der Türkei und neben dem Griechischen auch auf Zypern (sowie in der international nicht anerkannten Türkischen Republik Nordzypern). Außerdem wird das Türkische als lokale Amtssprache in Nordmazedonien, Rumänien und im Kosovo verwendet. Eigenbezeichnungen sind Türk dili, Türkçe [tyɾkt͡ʃe] und Türkiye Türkçesi.

Die türkische Sprache selbst weist eine Reihe von Dialekten auf, von denen der Istanbuler Dialekt von besonderer Bedeutung ist. Seine Phonetik ist die Basis der heutigen türkischen Hochsprache.[2] Bei der Einführung des lateinischen Alphabets für die türkische Sprache im Jahr 1928 wurde nicht auf die historische Orthographie des Osmanisch-Türkischen zurückgegriffen, sondern die Aussprache von Istanbul als Grundlage der Verschriftung herangezogen[3]. Die Dialekte innerhalb der Türkei werden in Gruppen der Schwarzmeerregion (Karadeniz Şivesi), Ostanatolien (Doğu Anadolu Şivesi), Südostanatolien (Güneydoğu Anadolu Şivesi), Zentralanatolien (İç Anadolu Şivesi), Ägäis (Ege Şivesi) und Mittelmeerregion (Akdeniz Şivesi) eingeteilt.

Die Alternativbenennung „Türkeitürkisch“ umfasst aber nicht nur die Türkei, sondern auch alle Gebiete des ehemaligen Osmanischen Reichs. Das bedeutet, dass auch die Balkan- oder Zyperntürken ein „Türkeitürkisch“ sprechen.[4]

土耳其语(Türkçe;[ˈtyɾctʃe] (![]() 聆听) ),是一种现有7300万到8700万人使用的语言,属突厥语族,主要在土耳其本土使用,并通行于阿塞拜疆、塞浦路斯、希腊、北马其顿、罗马尼亚、乌孜别克和土库曼斯坦,以及在西欧居住的数百万土耳其裔移民(主要集中在德国)。土耳其语是突厥语族诸语中使用人数最多的语言。

聆听) ),是一种现有7300万到8700万人使用的语言,属突厥语族,主要在土耳其本土使用,并通行于阿塞拜疆、塞浦路斯、希腊、北马其顿、罗马尼亚、乌孜别克和土库曼斯坦,以及在西欧居住的数百万土耳其裔移民(主要集中在德国)。土耳其语是突厥语族诸语中使用人数最多的语言。

土耳其语起源于中亚,其最早期的文字纪录可上溯至1200年前。随着奥斯曼帝国扩张,今日土耳其语的先驱奥斯曼土耳其语的影响力亦一同往西扩张。早期的土耳其语文字采用阿拉伯字母纪录,但在1928年,土耳其国父穆斯塔法·凯末尔·阿塔土克建立共和国后着手改革国家的语言,用以标志新国家与旧有奥斯曼帝国的分别,于是改用拉丁字母,直至现今。伴随这个改革的,还包括在新国语中去除旧有从波斯语及阿拉伯语借用的词汇,改为从土耳其语原有的字根去重新组合出有关借词所代表的意思。

土耳其语一个显著的特色,其元音和谐及大量胶着语的词缀变化,句法采用主宾动词序。土耳其语有着极严谨的尊称和敬语体系,但是词汇中没有名词类别和语法性别。

トルコ語(トルコご、Türkçe)は、アゼルバイジャン語やトルクメン語と同じテュルク諸語の南西語群(オグズ語群)に属する言語。

テュルク諸語のうち最大の話者数をもつ。トルコ語の話者が最も多いのはトルコ共和国であり、人口の約3分の2を占めるトルコ人の母語であるほか、公用語ともなっているため約7500万人のトルコ国民のほとんどはトルコ語を話すことができる[4]。キプロス共和国もギリシャ語と並んでトルコ語を公用語としている[5]が、実際にはキプロス紛争の結果1974年に国が南北に分断され、南部のみを領するようになったキプロス共和国内にはほぼトルコ人が存在しなくなったため、名目のみの公用語となっている。逆に島の北部を領有している北キプロス・トルコ共和国は約33万人の国民のほとんどをトルコ人が占めるようになったため、トルコ語が唯一の公用語となっている。

このほか、ブルガリアに約100万人[4]、ギリシャに約15万人、そのほかマケドニア共和国やコソボにも母語話者がいる。ドイツ・オーストリア・スイス・リヒテンシュタインなど西ヨーロッパ東部〜中央ヨーロッパのトルコ系移民社会(250万人以上)でも話されているが、現地で生まれてトルコ語が満足に話せない若者も増えている[4]。

アラビア語・ペルシア語からの借用語が極めて多い他、日常語にはブルガリア語・ギリシャ語など周辺の言語からの借用語も多く、近代に入った外来語にはフランス語からのものが多い。

主に中央アジア・トルキスタンを中心に広がるトルクメン語・カザフ語・キルギス語・ウイグル語などのテュルク諸語とは近縁関係にあり、中でも同じオグズ語群に属するアゼルバイジャン語とはかなりの部分相互理解が可能である[6]。

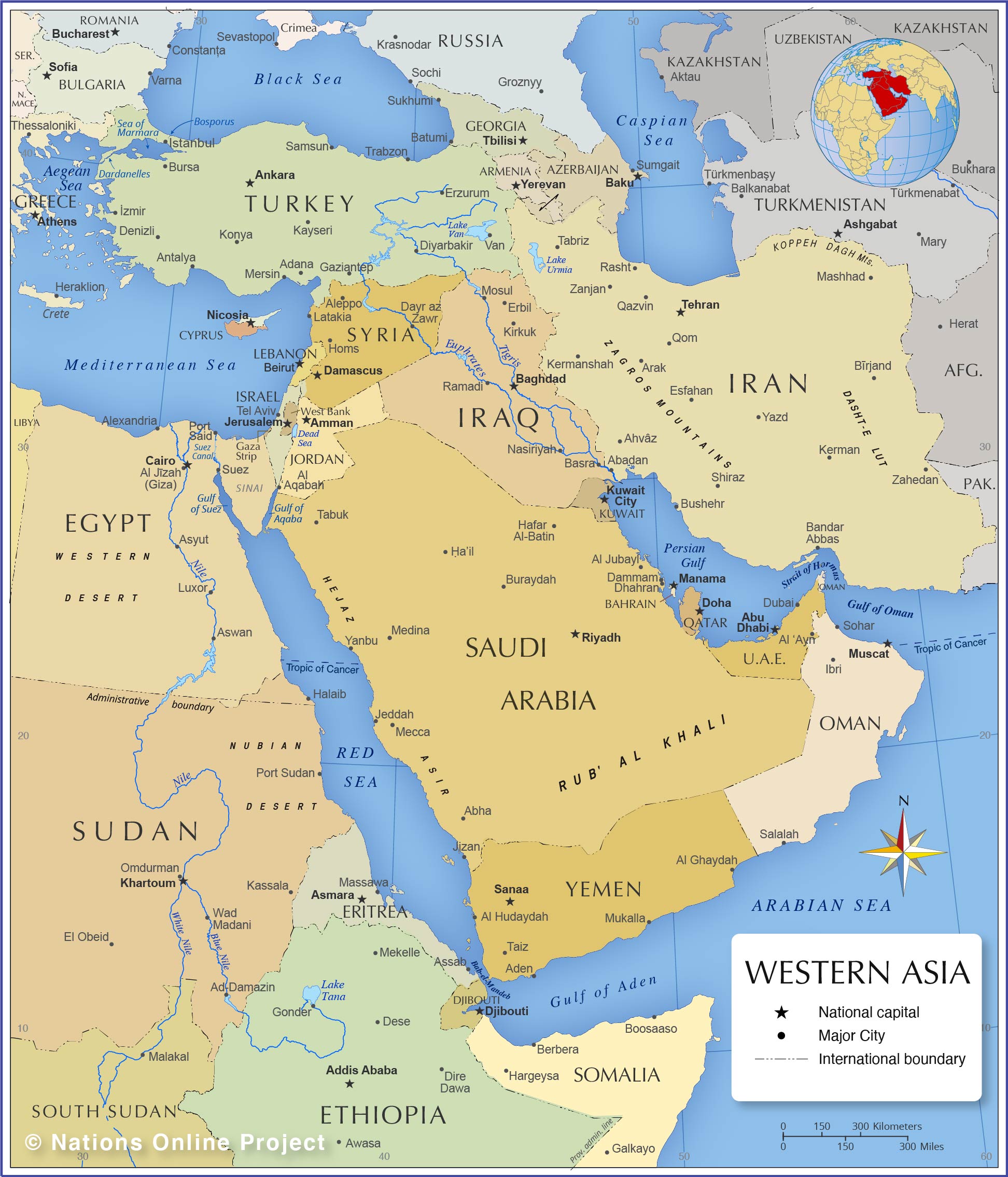

Turkish (Türkçe (![]() listen), Türk dili), also referred to as Istanbul Turkish[8][9][10] (İstanbul Türkçesi) or Turkey Turkish (Türkiye Türkçesi), is the most widely spoken of the Turkic languages, with around 70 to 80 million speakers, the national language of Turkey. Outside its native country, significant smaller groups of speakers exist in Iraq, Syria, Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, North Macedonia,[11] Northern Cyprus,[12] Greece,[13] the Caucasus, and other parts of Europe and Central Asia. Cyprus has requested that the European Union add Turkish as an official language, even though Turkey is not a member state.[14]

listen), Türk dili), also referred to as Istanbul Turkish[8][9][10] (İstanbul Türkçesi) or Turkey Turkish (Türkiye Türkçesi), is the most widely spoken of the Turkic languages, with around 70 to 80 million speakers, the national language of Turkey. Outside its native country, significant smaller groups of speakers exist in Iraq, Syria, Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, North Macedonia,[11] Northern Cyprus,[12] Greece,[13] the Caucasus, and other parts of Europe and Central Asia. Cyprus has requested that the European Union add Turkish as an official language, even though Turkey is not a member state.[14]

To the west, the influence of Ottoman Turkish—the variety of the Turkish language that was used as the administrative and literary language of the Ottoman Empire—spread as the Ottoman Empire expanded. In 1928, as one of Atatürk's Reforms in the early years of the Republic of Turkey, the Ottoman Turkish alphabet was replaced with a Latin alphabet.

The distinctive characteristics of the Turkish language are vowel harmony and extensive agglutination. The basic word order of Turkish is subject–object–verb. Turkish has no noun classes or grammatical gender. The language makes usage of honorifics and has a strong T–V distinction which distinguishes varying levels of politeness, social distance, age, courtesy or familiarity toward the addressee. The plural second-person pronoun and verb forms are used referring to a single person out of respect.

Le turc (autonyme : Türkçe ou Türk Dili) est une langue parlée principalement en Turquie et en Chypre du Nord. Il appartient à la famille des langues turques. Bien que les langues d'autres pays turcophones, principalement des républiques de l'ancienne URSS, soient proches du turc (surtout l'azéri et le turkmène), il existe d'importantes différences phonologiques, grammaticales ou lexicales entre ces langues.

Au-delà de la Turquie elle-même, le turc est utilisé dans l'ancien territoire de l'Empire ottoman par des populations d'origine ottomane, turcique ou des populations musulmanes qui ont adopté cette langue. Ces turcophones sont nombreux en Bulgarie, en Grèce (concentrés en Thrace occidentale), dans les Balkans (Bosnie-Herzégovine et Kosovo), dans la partie nord de l'île de Chypre (République turque de Chypre du Nord), dans le nord de l'Irak (surtout à Kirkouk), en Macédoine et en Roumanie (essentiellement en Dobroudja). C'est pourquoi le turc de Turquie est aussi nommé « turc osmanlı » (Osmanlı Türkçesi).

Le turc est, typologiquement, une langue agglutinante. Elle utilise principalement des suffixes et peu de préfixes. C'est une langue SOV (sujet-objet-verbe). Elle comporte un système d'harmonie vocalique.

La lingua turca (nome nativo Türkçe o Türk dili, Türkiye Türkçesi) è una lingua appartenente al ceppo Oghuz delle lingue turche, con circa 85 milioni di madrelingua[1] in Turchia, a Cipro, in Germania e sparsi per il mondo. Il turco era parlato nell'Impero ottomano usando, per la forma scritta, una versione modificata dell'alfabeto arabo. Nel 1928 Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, nei suoi sforzi per modernizzare la Turchia, rimpiazzò l'alfabeto arabo con una versione modificata dell'alfabeto latino. Ora il turco è regolato dall'Organizzazione linguistica turca. Il turco è parlato in Turchia e da minoranze di 35 altri paesi. È usato in stati come l'Azerbaijan, la Bulgaria, la Grecia, la parte settentrionale di Cipro, occupata dalla Turchia fin dal 1974, la Macedonia del Nord, il Kosovo e l'Uzbekistan.

El idioma turco (![]() Türkçe (?·i) o Türk dili) pertenece a la familia lingüística de las lenguas túrquicas, cuya área geográfica se extiende desde el occidente de China hasta los Balcanes. Las lenguas más próximas al turco son el azerí, el gagauzo y el turcomano.

Türkçe (?·i) o Türk dili) pertenece a la familia lingüística de las lenguas túrquicas, cuya área geográfica se extiende desde el occidente de China hasta los Balcanes. Las lenguas más próximas al turco son el azerí, el gagauzo y el turcomano.

Es oficial en Turquía, donde se habla desde la época medieval, cuando los turcos procedentes de Asia Central se instalaron en Anatolia, que entonces era parte del Imperio bizantino. Es oficial también en Chipre, donde comparte cooficialidad con el griego, así como en la autoproclamada República Turca del Norte de Chipre. En algunas zonas balcánicas se habla una variedad conocida como turco otomano (Osmanlı Türkçesi), que tiene diferencias con el turco de Turquía. En varios países de la Europa occidental existen importantes comunidades de hablantes de turco, emigradas de Turquía en fechas recientes.

Es una lengua aglutinante, como lo son el quechua, el finés, el japonés o el vasco, y por tanto se basa en un sistema de afijos añadidos a la raíz de las palabras que permiten expresar gran cantidad de significados con pocas palabras. El turco usa casi exclusivamente sufijos. Su morfología no suele tener excepciones y es altamente regular. Otras importantes características son la ausencia del género gramatical, el orden sintáctico es SOV, que es una lengua de núcleo final y que usa postposiciones.

Ha tenido varios sistemas de escritura. Se escribió con caracteres árabes (alfabeto turco otomano) adaptados desde el siglo XIII hasta la reforma ortográfica emprendida en los años 1920 por el gobierno de Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, que emprendió varias iniciativas de occidentalización del país para contribuir a su modernización. La reforma ortográfica vino acompañada de un intento de "depuración" nacionalista, es decir, de sustituir la ingente cantidad de préstamos lingüísticos (sobre todo árabes) por vocablos de raíz turca, objetivo vigente hoy en día que no ha cosechado los éxitos esperados.[cita requerida]

Está regulada por la Türk Dil Kurumu (TDK), la Sociedad de la Lengua Turca.

Туре́цкий язы́к (самоназвание: Türk dili (кратко: Türkçe [ˈt̪yɾktʃe] ![]() слушать), рус. историч. турской языкъ) — официальный язык Турции, входящий в тюркскую языковую семью. В качестве альтернативного названия в тюркологии используется также Türkiye Türkçesi («турецкий тюркский»).

слушать), рус. историч. турской языкъ) — официальный язык Турции, входящий в тюркскую языковую семью. В качестве альтернативного названия в тюркологии используется также Türkiye Türkçesi («турецкий тюркский»).

Современный турецкий язык относится к юго-западной (или западно-огузской) подгруппе тюркских языков. Языками, наиболее близкими к турецкому в лексическом, фонетическом и синтаксическом отношении, являются прежде всего балкано-тюркский язык гагаузов, распространённый на территории современных Молдавии, Румынии и Болгарии (собственно гагаузский и балкано-гагаузский), и южный диалект крымскотатарского языка. Чуть далее отстоит от литературного турецкого азербайджанский[3][страница не указана 536 дней] (сохранивший немало архаизмов и персидских заимствований и образующий с восточно-анатолийскими диалектами турецкого языка диалектный континуум) и, ввиду ряда фонетических и некоторых грамматических отличий, туркменский язык. Турецкий язык и в особенности его северо-западные диалекты, и гагаузский — оба сближаются с печенежским языком: ср. переходы в печенежском языке g/k > y в конце слов (beg > bey), k/g > в v интервокальной позиции (между гласными, напр., kökerçi > küverçi), t > d в начале слов (tağ > dağ), с полной аналогией в турецком и гагаузском языках: bey, güvercin, dağ/daa.

Der Topkapı-Palast (osmanisch طوپقپو سرايى Topkapı Sarayı, „Kanonentor-Palast“) in Istanbul, im Deutschen auch Topkapi-Palast oder Topkapi-Serail, war jahrhundertelang der Wohn- und Regierungssitz der Sultane sowie das Verwaltungszentrum des Osmanischen Reiches.

Mit dem Bau wurde bald nach der Eroberung Konstantinopels (1453) durch Sultan Mehmed II. begonnen. Zunächst ließ er einen Palast auf dem heutigen Beyazıtplatz (Beyazıt Meydanı) errichten. Wenig später entschied er sich dann aber für ein zweites Projekt an anderer Stelle. Seit 1459 wurde auf der heute Sarayburnu genannten Landspitze zwischen Goldenem Horn und Marmarameer ein neuer, zunächst aus zwei Höfen (heute 2. und 3. Hof) bestehender Palast errichtet, der 1468 vollendet war. Dabei wurden Teile des byzantinischen Mangana-Palastes überbaut. 1478 wurde eine Wehrmauer im Abstand um den Palast fertiggestellt, die u. a. den Raum für den heutigen ersten Hof bildete. Damit war die Grundstruktur des Palastes bereits im 15. Jahrhundert in den wesentlichen Zügen festgelegt. Der Bau ist somit auch nach den späteren Umgestaltungen eines der bedeutendsten Architekturzeugnisse der Renaissanceepoche in Europa.

Ihr heutiges Aussehen erhielt die Anlage durch umfangreiche Renovierungen und Erweiterungen bis zum Anfang des 18. Jahrhunderts. Die letzte große Ergänzung war der Große Pavillon (Mecidiye Köşkü), der 1840 vom armenischen Architekten Sarkis Balyan errichtet wurde. Seit Mehmed II. residierten alle osmanischen Herrscher im Topkapı-Palast, bis Sultan Abdülmecid I. im Jahre 1856 das neue Dolmabahçe Sarayı auf der anderen Seite des Goldenen Horns am Ufer des Bosporus bezog. Beide Paläste sind heute Museen.

Der Palast besteht nicht aus einem einzelnen, sondern getreu der türkischen Tradition aus mehreren Gebäuden in einem großen Garten. Mit einer Fläche von über 69 Hektar und bis zu 5000 Bewohnern war der Palast eine eigene Stadt. Man nannte ihn anfangs Saray-ı Cedîd-i Âmire / سرای جديد عامره oder Yeni Saray / يکی سرای / ‚Neuer Palast‘, bevor sich im 18. Jahrhundert der Name Topkapı Sarayı durchsetzte, der sich von der palasteigenen Kanonengießerei ableitete.

Der Palast ist in vier Höfe unterteilt, die jeweils durch eigene Tore erreicht werden. Mit seiner Lage auf einer Landspitze bietet er eine beispiellose Panoramasicht auf Istanbul, den Bosporus und das Goldene Horn.

托普卡珀皇宫(土耳其语:Topkapı Sarayı,奥斯曼土耳其语:طوپقپو سرايى)是位处土耳其伊斯坦布尔的一座皇宫,自1465年至1853年一直都是奥斯曼帝国苏丹在城内的官邸及主要居所[2]。托普卡珀皇宫是昔日举行国家仪式及皇室娱乐的场所,现今则是当地主要的观光胜地。托普卡珀皇宫翻译过来成为“大炮之门”,昔日碉堡内曾放置大炮,故以此命名[3]。

征服拜占庭帝国君士坦丁堡的苏丹穆罕默德二世在1459年下令动工兴建托普卡珀皇宫[4]。皇宫由四个庭院及其他矮小的建筑物组成[5],昔日有大约四千人居住[6],以往的皇宫覆盖着一个广大的海岸地区。在多个世纪以来,皇宫经过扩建和整修,例如1509年的地震及1665年的火灾后[7][8],皇宫都进行过维修。

托普卡珀皇宫在十七世纪的重要性下降,那时的苏丹较喜欢到博斯普鲁斯海峡附近的新宫廷。1853年,苏丹阿卜杜勒-迈吉德一世把皇宫迁至新落成的朵巴马切皇宫[9],杜马伯爵皇宫是伊斯坦布尔内第一个欧式宫廷[10]。托普卡珀皇宫的帝国宝库、图书馆、清真寺及造币局都一并保留。

奥斯曼帝国在1921年灭亡。1924年4月3日,托普卡珀皇宫在政府政令下变成帝国时代的博物馆[11]。托普卡珀皇宫博物馆由文化旅游部管理。皇宫里有大量的屋宇和厅堂,但现今只有最重要的部分开放给公众,皇宫由部门的职员以及土耳其军方的武装守卫把守。托普卡珀皇宫是奥斯曼建筑的代表作,包含大量的瓷器、官服、武器、盾牌、盔甲、奥斯曼细密画、伊斯兰的书法原稿、壁画以及奥斯曼的珠宝宝物。

托比卡皇宫与邻近的其他历史遗产同属“伊斯坦布尔历史地区”,该区在1985年成为联合国教育、科学及文化组织的世界遗产,托普卡珀皇宫被描述为“奥斯曼帝国时期皇宫的表率。”[12]

トプカプ宮殿(土:Topkapı Sarayı、「大砲の門宮殿」の意)は、15世紀中頃から19世紀中頃までオスマン帝国の君主が居住した宮殿。イスタンブール旧市街のある半島の先端部分、三方をボスポラス海峡とマルマラ海、金角湾に囲まれた丘に位置する。

発音は「トプカプ」(トルコ語発音: [ˈtopkapɯ saraˈjɯ])が正しいが、日本語ではしばしば「トプカピ宮殿」と表記されることがある[1]。

トプカプ宮殿と呼ばれるようになったのは19世紀の皇帝が去った後からで、それ以前はベヤズットスクエア(英語版)に元々あった宮殿(旧宮殿)に対する「新宮殿」ということで、新宮殿を意味する「イェニ・サライ」、帝国新宮殿を意味する「サライ・ジェディード」(オスマン語: سراى جديد عامره)と呼ばれた。また、イスタンブールに営まれた多くの宮殿のうちの正宮殿として「帝王の宮殿」(サライ・ヒュマーユーン)とも呼ばれた。

宮殿はよく保存修復され、現在は博物館として公開されているが、15世紀に建設されて以来増改築を繰り返しており、現在見られる姿を保ちつづけているわけではない。

The Topkapı Palace (Turkish: Topkapı Sarayı[2] or in Ottoman Turkish: طوپقپو سرايى, Ṭopḳapu Sarāyı),[3] or the Seraglio,[4] is a large museum in Istanbul, Turkey. In the 15th century, it served as the main residence and administrative headquarters of the Ottoman sultans.

Construction began in 1459, ordered by Mehmed the Conqueror, six years after the conquest of Constantinople. Topkapı was originally called the "New Palace" (Yeni Saray or Saray-ı Cedîd-i Âmire) to distinguish it from the Old Palace in Beyazıt Square. It was given the name Topkapı, meaning Cannon Gate, in the 19th century.[5] The complex was expanded over the centuries, with major renovations after the 1509 earthquake and the 1665 fire. The palace complex consists of four main courtyards and many smaller buildings. Female members of the Sultan's family lived in the harem, and leading state officials, including the Grand vizier, held meetings in the Imperial Council building.

After the 17th century, Topkapı gradually lost its importance. The sultans of that period preferred to spend more time in their new palaces along the Bosphorus. In 1856, Sultan Abdulmejid I decided to move the court to the newly built Dolmabahçe Palace. Topkapı retained some of its functions including the imperial treasury, library and mint.

Following the end of the Ottoman Empire in 1923, Topkapı was transformed into a museum by a government decree dated April 3, 1924. The Topkapı Palace Museum is administered by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. The palace complex has hundreds of rooms and chambers, but only the most important are accessible to the public today, including the Ottoman imperial harem and the treasury, called hazine where the Spoonmaker's Diamond and Topkapi Dagger are on display. The museum collection also includes Ottoman clothing, weapons, armor, miniatures, religious relics, and illuminated manuscripts like the Topkapi manuscript. The complex is guarded by officials of the ministry as well as armed guards of the Turkish military. Topkapı Palace is part the Historic Areas of Istanbul, a group of sites in Istanbul that were added to the UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985.[6]

Le palais de Topkapı (en turc : Topkapı Sarayı [top.kɑ.'pɯ sɑ.ɾɑ.'jɯ], ou en turc ottoman : طوپقپو سرايى) est un palais d'Istanbul, en Turquie. De 1465 à 1853, il est la résidence urbaine, principale et officielle, du sultan ottoman. Le palais est construit sur l’emplacement de l’acropole de l’antique Byzance. Il domine la Corne d'Or, le Bosphore et la mer de Marmara. Le nom de « Topkapı Sarayı » signifie littéralement « palais de la porte des canons », d'après le nom d'une porte voisine aujourd'hui disparue. Il s'étend sur 700 000 m² (70 ha), et est entouré de cinq kilomètres de remparts.

La construction commence en 1459, sous le sultan Mehmed II, conquérant de la Constantinople byzantine. Par la suite, le palais impérial connaît de nombreux agrandissements : la construction du harem au cours du XVIe siècle, ou les modifications après le séisme de 1509 et l'incendie de 1665. Le palais est un complexe architectural composé de quatre cours principales et de nombreux bâtiments annexes. Au plus fort de son existence comme résidence impériale, il abritait plus de 4 000 personnes et s'étendait sur une zone encore plus vaste.

Le palais de Topkapı perd progressivement de son importance à partir de la fin du XVIIe siècle, lorsque les sultans lui préfèrent un nouveau palais, le long du Bosphore. En 1853, le sultan Abdülmecid Ier décide de déplacer sa cour vers le palais de Dolmabahçe, premier palais de style européen de la ville, dont la construction vient de se terminer. Certaines fonctions, comme le trésor impérial, la bibliothèque, les mosquées et la monnaie restent à Topkapı.

Après la fin de l'Empire ottoman en 1921, le palais de Topkapı est transformé en musée de l'ère ottomane par décret du nouveau gouvernement républicain du 3 avril 1924. Le musée du palais de Topkapı est, depuis, placé sous l'administration du ministère de la culture et du tourisme. Si le palais comporte des centaines de pièces et de chambres, seules les plus importantes sont habituellement ouvertes aux visiteurs. Le complexe est surveillé par des fonctionnaires du ministère ainsi que des gardes de l'armée turque. Il offre de nombreux exemples de l'architecture ottomane et conserve d'importantes collections de porcelaine, de vêtements, d'armes, de boucliers, d'armures, de miniatures ottomanes, de manuscrits de calligraphie islamique et de peintures murales, ainsi qu'une exposition permanente du trésor et de la joaillerie de l'époque ottomane.

Le palais de Topkapı est répertorié parmi les monuments de la zone historique d'Istanbul. Il a été inscrit sur la liste du patrimoine mondial de l'UNESCO en 1985, où il est décrit comme « un ensemble incomparable de bâtiments construits sur quatre siècles, unique par la qualité architecturale de ses bâtiments autant que par leur organisation qui reflète celle de la cour ottomane »1.

Il Palazzo Topkapı, o Serraglio di Topkapı (in tu. Topkapı Sarayı; ot. طوپقپو سرايى) è il complesso palaziale che fu a un tempo residenza del sultano ottomano e centro amministrativo dell'Impero ottomano dalla seconda metà del XV secolo al 1856.

Costruito per volontà di Maometto II sul c.d. "Promontorio del Serraglio" (tu. Sarayburnu) per dominare sulla città di Costantinopoli (attuale Istanbul), era originariamente conosciuto come Yeni Saray, anche Saray-ı Cedîd-i Âmire, lett. "Nuovo Serraglio/Palazzo" in contrapposizione al "Vecchio Palazzo" che i turchi avevano ereditato dagli imperatori bizantini. Venne ribattezzato "Topkapı" (lett. "Cancello del Cannone") solo nel XIX secolo[2]. Il complesso fu oggetto di numerosi ampliamenti e restauri per oltre tre secoli (i più noti dei quali successivi al Terremoto d'Istanbul del 1509 ed al grande incendio che devastò il palazzo nel 1665), salvo poi il venir progressivamente abbandonato dai sultani in funzione di più moderne residenze nel corso dell'Ottocento. Ridimensionato a semplice sede della tesoreria (hazine), della libreria imperiale e della zecca di stato per volontà del sultano Abdülmecid I nel 1856, divenne il primo grande museo della Repubblica di Turchia nel 1924.

Il Museo del Palazzo Topkapı è oggi amministrato dal Ministero della Cultura e del Turismo turco. Delle centinaia di stanza e camere del complesso, solo le più importanti sono accessibili al pubblico: l'harem, la tesoreria (ove sono conservati il Diamante del fabbricante di cucchiai e la Daga Topapı), ecc. Il patrimonio museale comprende anche un vastissimo assortimento di vestiario, armi, armature, miniature, reliquie religiose e manoscritti illustrati (es. il c.d. "Rotolo Topkapı"). A guardia del museo sono preposti sia ufficiali del ministero sia guardie armate dell'esercito turco.

Il Palazzo Topkapı è parte delle "Aree storiche d'Istanbul", un insieme di siti archeologico-museali facenti parte del Patrimonio dell'umanità UNESCO dal 1985[3].

El Palacio de Topkapi (Topkapı Sarayı en turco, literalmente el 'Palacio de la Puerta de los Cañones' — por estar situado cerca de una puerta de ese nombre), situado en Estambul, fue el centro administrativo del Imperio otomano desde 1465 hasta 1853. La construcción del palacio fue ordenada por el sultán Mehmed II en 1459 y fue completada en 1465. El palacio está situado sobre el Sarayburnu, entre el Cuerno de Oro y el Mar de Mármara, desde él se tiene una espléndida vista del Bósforo. Está formado por muchos pequeños edificios construidos juntos y rodeados por cuatro patios.

El palacio está construido siguiendo las normas de la arquitectura seglar turca, siendo su máximo ejemplo. Es un entramado complejo de edificios, unidos por patios o jardines siendo la superficie total del complejo de 700.000 m2, rodeados por una muralla bizantina.

En 1853, el sultán Abdulmecid decidió trasladar su residencia al recién construido y moderno Palacio de Dolmabahçe. En la actualidad, el Topkapi es un museo de la época imperial, siendo una de las mayores atracciones turísticas de Estambul.

Топкапы́ (Топкапи; тур. Topkapı), устар. Сераль (фр. Serail) — главный дворец Османской империи до середины XIX века. Расположен в историческом центре Стамбула, на мысе Сарайбурну, в месте впадения Босфора и Золотого Рога в Мраморное море.

После падения Османской империи дворец превращён в музей — один из крупнейших по площади в мире. Число экспонатов, выставленных для общего обозрения, достигает 65 000 единиц (и это только десятая часть коллекции).

Общая площадь дворцово-паркового ансамбля, окружённого высокими стенами, со всеми примыкающими садами и пристройками, составляет более 700 тыс. кв. м. Это один из исторических районов Стамбула, включённых в 1985 г. в список Всемирного наследия.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan

Egypt

Egypt

Armenia

Armenia

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan

Bahrain

Bahrain

Georgia

Georgia

Iraq

Iraq

Iran

Iran

Israel

Israel

Yemen

Yemen

Jordan

Jordan

Katar

Katar

Kuwait

Kuwait

Libanon

Libanon

Oman

Oman

Palestine

Palestine

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

Syria

Syria

Turkey

Turkey

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates

Cyprus

Cyprus

Beijing Shi-BJ

Beijing Shi-BJ

Belarus

Belarus

Berlin

Berlin

Brandenburg

Brandenburg

Bremen

Bremen

China

China

Germany

Germany

France

France

Gansu Sheng-GS

Gansu Sheng-GS

Hebei Sheng-HE

Hebei Sheng-HE

Heilongjiang Sheng-HL

Heilongjiang Sheng-HL

Henan Sheng-HA

Henan Sheng-HA

Hubei Sheng-HB

Hubei Sheng-HB

Hunan Sheng-HN

Hunan Sheng-HN

Iran

Iran

Italy

Italy

Jiangsu Sheng-JS

Jiangsu Sheng-JS

Jilin Sheng-JL

Jilin Sheng-JL

Kasachstan

Kasachstan

Liaoning Sheng-LN

Liaoning Sheng-LN

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Netherlands

Netherlands

Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

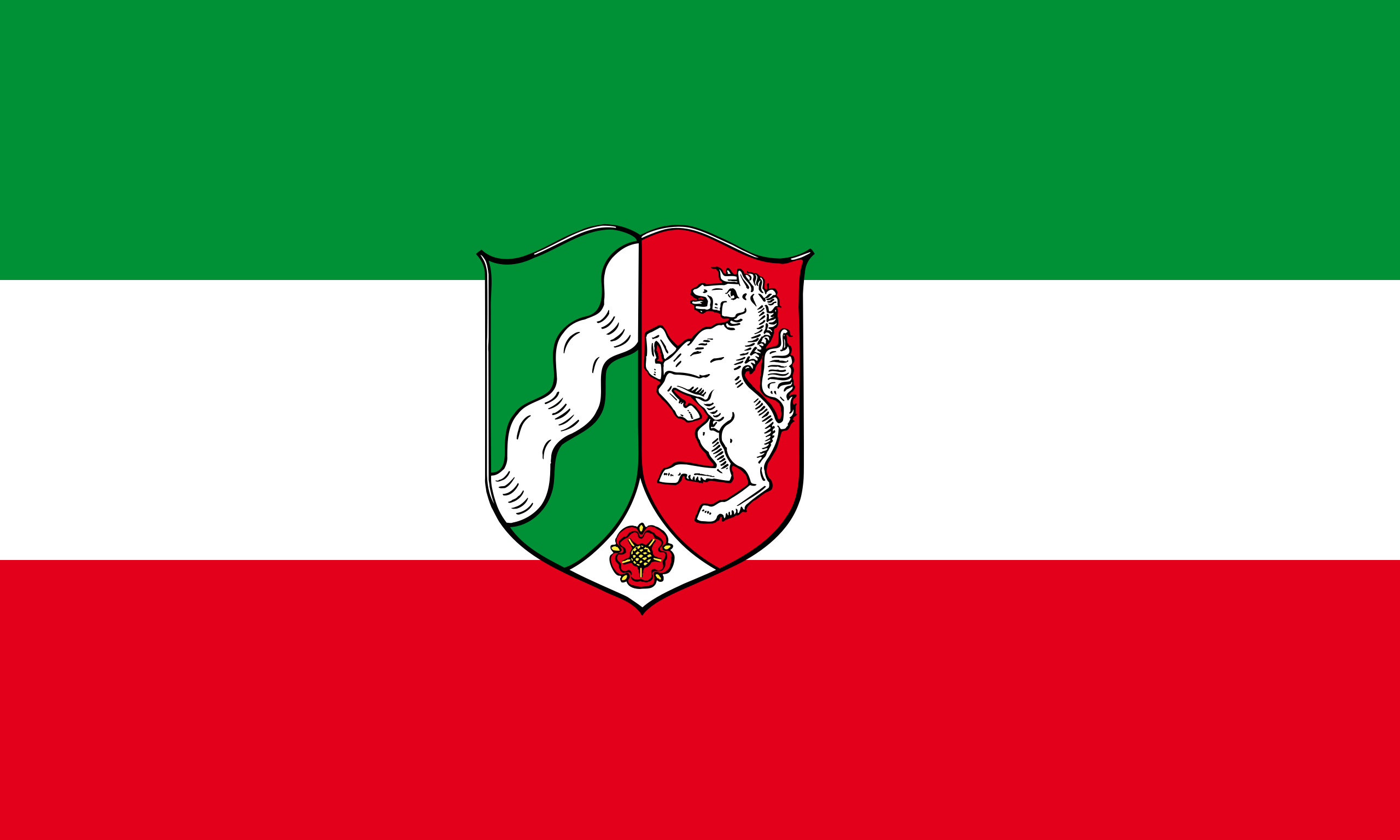

North Rhine-Westphalia

North Rhine-Westphalia

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Russia

Russia

Saxony

Saxony

Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shandong Sheng-SD

Shandong Sheng-SD

Shanxi Sheng-SX

Shanxi Sheng-SX

Sichuan Sheng-SC

Sichuan Sheng-SC

Spain

Spain

Turkey

Turkey

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

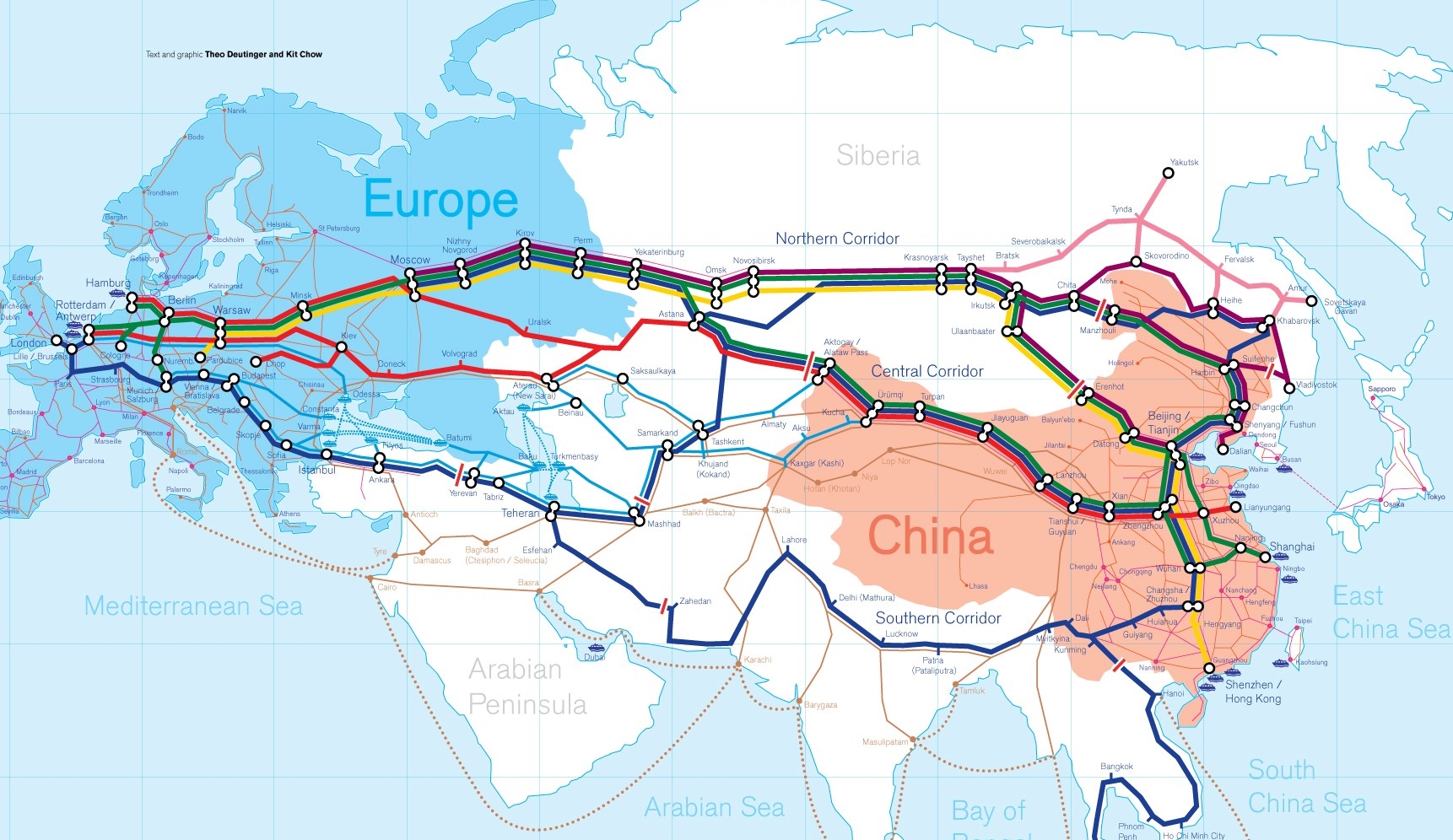

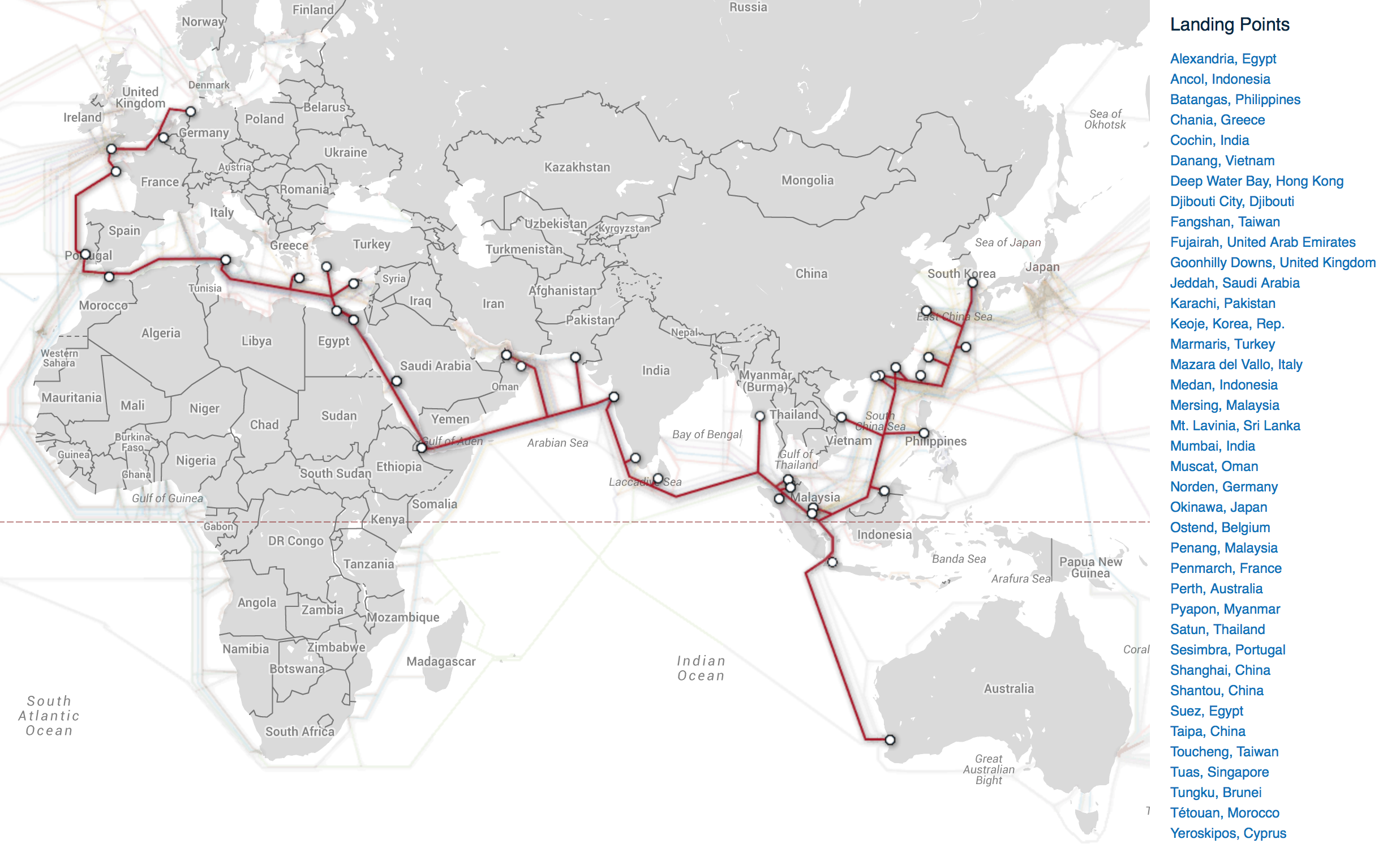

Die Neue eurasische Kontinentalbrücke (chinesisch 新亚欧大陆桥, Pinyin Xīn Yà-Ōu Dàlù Qiáo, englisch New Eurasian Continental Bridge), die auch Zweite eurasische Kontinentalbrücke (第二亚欧大陆桥, Dì'èr Yà-Ōu Dàlù Qiáo, englisch Second Eurasian Continental Bridge) genannt wird, ist eine 10.870 Kilometer[1] lange Eisenbahnverbindung, die Rotterdam in Europa mit der ostchinesischen Hafenstadt Lianyungang in der Provinz Jiangsu verbindet.

Sie besteht seit 1990 und führt durch die Dsungarische Pforte (Grenzbahnhof Alashankou). Die Lan-Xin-Bahn (chinesisch 兰新铁路, Pinyin Lán-Xīn Tiělù), also die Strecke von Lanzhou nach Ürümqi (in Xinjiang), ist ein Teil von ihr.

Es gibt eine nördliche, mittlere und südliche Route.[2] Die mittlere Strecke verläuft durch Kasachstan über Dostyk, Aqtogai, Astana, Samara, Smolensk, Brest, Warschau, Berlin zum Hafen von Rotterdam.[3] Vom slowakischen Košice soll auch eine Abzweigung in den Großraum Wien führen, siehe Breitspurstrecke Košice–Wien.

亚欧大陆桥,或新世纪亚欧大陆桥,是在中国大陆的新闻报道中经常出现的一个词语,特指从中国东部的沿海港口(有时特指连云港),沿陇海铁路、兰新铁路、北疆铁路,通过中亚、西亚到达欧洲的铁路路线。这条铁路在中国境外的具体走向,并没有任何官方文件精确指明,一说是经哈萨克斯坦、乌兹别克斯坦、土库曼斯坦、伊朗到达土耳其;一说是经俄罗斯、白俄罗斯、波兰、德国到达荷兰鹿特丹。全长10,800.32公里,1990年9月12日贯通。

The New Eurasian Land Bridge, also called the Second or New Eurasian Continental Bridge, is the southern branch of the Eurasian Land Bridge rail links running through China. The Eurasian Land Bridge is the overland rail link between Asia and Europe.

Due to a break-of-gauge between standard gauge used in China and the Russian gauge used in the former Soviet Union countries, containers must be physically transferred from Chinese to Kazakh railway cars at Dostyk on the Chinese-Kazakh border and again at the Belarus-Poland border where the standard gauge used in western Europe begins. This is done with truck-mounted cranes.[1] Chinese media often states that the New Eurasian Land/Continental Bridge extends from Lianyungang to Rotterdam, a distance of 11,870 kilometres (7,380 mi). The exact route used to connect the two cities is not always specified in Chinese media reports, but appears to usually refer to the route which passes through Kazakhstan.

All rail freight from China across the Eurasian Land Bridge must pass north of the Caspian Sea through Russia at some point. A proposed alternative would pass through Turkey and Bulgaria,[2] but any route south of the Caspian Sea must pass through Iran.[1]

Kazakhstan's President Nursultan Nazarbayev urged Eurasian and Chinese leaders at the 18th Shanghai Cooperation Organisation to construct the Eurasian high-speed railway (EHSRW) following a Beijing-Astana-Moscow-Berlin.[3]

The Eurasian Land Bridge (Russian: Евразийский сухопутный мост, Yevraziyskiy sukhoputniy most), sometimes called the New Silk Road (Новый шёлковый путь, Noviy shyolkoviy put'), or Belt and Road Initiative is the rail transport route for moving freight and passengers overland between Pacific seaports in the Russian Far East and China and seaports in Europe. The route, a transcontinental railroad and rail land bridge, currently comprises the Trans-Siberian Railway, which runs through Russia and is sometimes called the Northern East-West Corridor, and the New Eurasian Land Bridge or Second Eurasian Continental Bridge, running through China and Kazakhstan. As of November 2007, about 1% of the $600 billion in goods shipped from Asia to Europe each year were delivered by inland transport routes.[1]

Completed in 1916, the Trans-Siberian connects Moscow with Russian Pacific seaports such as Vladivostok. From the 1960s until the early 1990s the railway served as the primary land bridge between Asia and Europe, until several factors caused the use of the railway for transcontinental freight to dwindle. One factor is that the railways of the former Soviet Union use a wider rail gauge than most of the rest of Europe as well as China. Recently, however, the Trans-Siberian has regained ground as a viable land route between the two continents.[why?]

China's rail system had long linked to the Trans-Siberian via northeastern China and Mongolia. In 1990 China added a link between its rail system and the Trans-Siberian via Kazakhstan. China calls its uninterrupted rail link between the port city of Lianyungang and Kazakhstan the New Eurasian Land Bridge or Second Eurasian Continental Bridge. In addition to Kazakhstan, the railways connect with other countries in Central Asia and the Middle East, including Iran. With the October 2013 completion of the rail link across the Bosphorus under the Marmaray project the New Eurasian Land Bridge now theoretically connects to Europe via Central and South Asia.

Proposed expansion of the Eurasian Land Bridge includes construction of a railway across Kazakhstan that is the same gauge as Chinese railways, rail links to India, Burma, Thailand, Malaysia and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, construction of a rail tunnel and highway bridge across the Bering Strait to connect the Trans-Siberian to the North American rail system, and construction of a rail tunnel between South Korea and Japan. The United Nations has proposed further expansion of the Eurasian Land Bridge, including the Trans-Asian Railway project.

El Nuevo Puente de Tierra de Eurasia es también llamado el Segundo o Nuevo Puente Continental de Eurasia. Es la rama meridional de las conexiones ferroviarias del Puente de Tierra de Eurasia (también conocido como "Nueva Ruta de la Seda") que se extienden a través de la República Popular China, atravesando Kazajistán, Rusia y Bielorrusia. El Puente de Tierra de Eurasia es el enlace ferroviario terrestre entre Asia Oriental y Europa.

La Nueva Ruta de la Seda (en ruso, Новый шёлковый путь, Noviy shyolkoviy put), o Puente Terrestre Euroasiático, es la ruta de transporte ferroviario para el movimiento de tren de mercancías y tren de pasajeros por tierra entre los puertos del Pacífico, en el Lejano Oriente ruso y chino y los puertos marítimos en Europa.

La ruta, un ferrocarril transcontinental y puente terrestre, actualmente comprende el ferrocarril Transiberiano, que se extiende a través de Rusia, y el nuevo puente de tierra de Eurasia o segundo puente continental de Eurasia, que discurre a través de China y Kazajistán, también se van a construir carreteras entre las ciudades de la ruta. A partir de noviembre de 2007, aproximadamente el 1% de los 600 millones de dólares en bienes enviados desde Asia a Europa cada año se entregaron por vías de transporte terrestre.1

Terminado en 1916, el tren Transiberiano conecta Moscú con el lejano puerto de Vladivostok en el océano Pacífico, el más largo del mundo en el Lejano Oriente e importante puerto del Pacífico. Desde la década de 1960 hasta principios de 1990 el ferrocarril sirvió como el principal puente terrestre entre Asia y Europa, hasta que varios factores hicieron que el uso de la vía férrea transcontinental para el transporte de carga disminuyese.

Un factor es que los ferrocarriles de la Unión Soviética utilizan un ancho de vía más ancho en los rieles que la mayor parte del resto de Europa y China, y el transporte en barcos de carga por el canal de Suez en Egipto, construido por Inglaterra. El sistema ferroviario de China se une al Transiberiano en el noreste de China y Mongolia. En 1990 China añadió un enlace entre su sistema ferroviario y el Transiberiano a través de Kazajistán. China denomina a su enlace ferroviario ininterrumpido entre la ciudad portuaria de Lianyungang y Kazajistán como el «Puente terrestre de Nueva Eurasia» o «Segundo puente continental Euroasiático». Además de Kazajistán, los ferrocarriles conectan con otros países de Asia Central y Oriente Medio, incluyendo a Irán. Con la finalización en octubre de 2013 de la línea ferroviaria a través del Bósforo en el marco del proyecto Marmaray el puente de tierra de Nueva Eurasia conecta ahora teóricamente a Europa a través de Asia Central y del Sur.

La propuesta de ampliación del Puente Terrestre Euroasiático incluye la construcción de un ferrocarril a través de Kazajistán con el mismo ancho de vía que los ferrocarriles chinos, enlaces ferroviarios a la India, Birmania, Tailandia, Malasia y otros países del sudeste asiático, la construcción de un túnel ferroviario y un puente de carretera a través del estrecho de Bering para conectar el Transiberiano al sistema ferroviario de América del Norte, y la construcción de un túnel ferroviario entre Corea del Sur y Japón. Las Naciones Unidas ha propuesto una mayor expansión del Puente Terrestre Euroasiático, incluyendo el proyecto del ferrocarril transasiático.

Новый шёлковый путь (Евразийский сухопутный мост — концепция новой паневразийской (в перспективе — межконтинентальной) транспортной системы, продвигаемой Китаем, в сотрудничестве с Казахстаном, Россией и другими странами, для перемещения грузов и пассажиров по суше из Китая в страны Европы. Транспортный маршрут включает трансконтинентальную железную дорогу — Транссибирскую магистраль, которая проходит через Россию и второй Евразийский континентальный мост[en], проходящий через Казахстан[1]. Поезда по этому самому длинному в мире грузовому железнодорожному маршруту из Китая в Германию будут идти 15 дней, что в 2 раза быстрее, чем по морскому маршруту через Суэцкий канал[2].

Идея Нового шёлкового пути основывается на историческом примере древнего Великого шёлкового пути, действовавшего со II в. до н. э. и бывшего одним из важнейших торговых маршрутов в древности и в средние века. Современный НШП является важнейшей частью стратегии развития Китая в современном мире — Новый шёлковый путь не только должен выстроить самые удобные и быстрые транзитные маршруты через центр Евразии, но и усилить экономическое развитие внутренних регионов Китая и соседних стран, а также создать новые рынки для китайских товаров (по состоянию на ноябрь 2007 года, около 1 % от товаров на 600 млрд долл. из Азии в Европу ежегодно доставлялись наземным транспортом[3]).

Китай продвигает проект «Нового шёлкового пути» не просто как возрождение древнего Шёлкового пути, транспортного маршрута между Востоком и Западом, но как масштабное преобразование всей торгово-экономической модели Евразии, и в первую очередь — Центральной и Средней Азии. Китайцы называют эту концепцию — «один пояс — один путь». Она включает в себя множество инфраструктурных проектов, которые должны в итоге опоясать всю планету. Проект всемирной системы транспортных коридоров соединяет Австралию и Индонезию, всю Центральную и Восточную Азию, Ближний Восток, Европу, Африку и через Латинскую Америку выходит к США. Среди проектов в рамках НШП планируются железные дороги и шоссе, морские и воздушные пути, трубопроводы и линии электропередач, и вся сопутствующая инфраструктура. По самым скромным оценкам, НШП втянет в свою орбиту 4,4 миллиарда человек — более половины населения Земли[4].

Предполагаемое расширение Евразийского сухопутного моста включает в себя строительство железнодорожных путей от трансконтинентальных линий в Иран, Индию, Мьянму, Таиланд, Пакистан, Непал, Афганистан и Малайзию, в другие регионы Юго-Восточной Азии и Закавказья (Азербайджан, Грузия). Маршрут включает тоннель Мармарай под проливом Босфор, паромные переправы через Каспийское море (Азербайджан-Иран-Туркменистан-Казахстан) и коридор Север-Юг.Организация Объединенных Наций предложила дальнейшее расширение Евразийского сухопутного моста, в том числе проекта Трансазиатской железной дороги (фактически существует уже в 2 вариантах).

Для развития инфраструктурных проектов в странах вдоль Нового шёлкового пути и Морского Шёлкового пути и с целью содействия сбыту китайской продукции в декабре 2014 года был создан инвестиционный Фонд Шёлкового пути[5].

8 мая 2015 года было подписано совместное заявление Президента РФ В. Путина и Председателя КНР Си Цзиньпина о сотрудничестве России и Китая, в рамках ЕАЭС и трансевразийского торгово-инфраструктурного проекта экономического пояса «Шёлковый путь». 13 июня 2015 года был запущен самый длинный в мире грузовой железнодорожный маршрут Харбин — Гамбург (Германия), через территорию России.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan

Egypt

Egypt

Algeria

Algeria

History

History

K 500 - 1000 AD

K 500 - 1000 AD

Iraq

Iraq

Iran

Iran

Yemen

Yemen

Jordan

Jordan

Katar

Katar

Comoros

Comoros

Libanon

Libanon

Libya

Libya

Malediven

Malediven

Morocco

Morocco

Pakistan

Pakistan

Religion

Religion

Islam

Islam

Republic of the Sudan

Republic of the Sudan

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

Somalia

Somalia

Syria

Syria

Tajikistan

Tajikistan

Tunisia

Tunisia

Turkey

Turkey

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

Verteilung muslimischer Glaubensrichtungen: Grün: sunnitische Gebiete; Rot: schiitische Gebiete; Blau: Ibaditen (Oman)

Die Sunniten bilden die größte Glaubensgruppe im Islam. Ihre Glaubensrichtung selbst wird als Sunnitentum oder Sunnismus bezeichnet. Die Bezeichnung ist von dem arabischen Wort Sunna (‚Brauch, Handlungsweise, überlieferte Norm, Tradition‘) abgeleitet. Diejenigen, die der sunnat an-nabī, der „Sunna des Propheten“ (sc. Mohammed), folgen, werden im Arabischen als ahl as-sunna („Leute der Sunna“) und im Türkischen als Ehl-i Sünnet bezeichnet, was im Deutschen üblicherweise als „Sunniten“ wiedergegeben wird. Neben ahl as-sunna wird im Arabischen auch der erweiterte Ausdruck ahl as-sunna wal-dschamāʿa (arabisch أهل السنة والجماعة, DMG ahl as-sunna wal-ǧamāʿa ‚Leute der Sunna und der Gemeinschaft‘) verwendet. Die Glaubenslehren der Sunniten werden in verschiedenen Glaubensbekenntnissen dargestellt, die sich je nach dogmatischer Ausrichtung der Autoren unterscheiden.

Heute gelten die Schiiten als die wichtigste Gegengruppe zu den Sunniten, allerdings hat sich das sunnitische Selbstbewusstsein im Mittelalter nicht nur in Absetzung zu den Schiiten, sondern auch zu den Charidschiten, Qadariten und Murdschi'iten herausgebildet. Über die Frage, welche dogmatischen Lehrrichtungen dem Sunnitentum angehören, besteht unter den muslimischen Gelehrten keine Einigkeit. Eine der wenigen internationalen Initiativen zur Klärung der sunnitischen Identität war die Sunnitenkonferenz von Grosny im August 2016. Auf ihr wurden die Takfīrī-Salafisten und andere extremistische Gruppen wie der Islamische Staat aus dem sunnitischen Islam ausgeschlossen.[1]

逊尼派(阿拉伯语:أهل السنة والجماعة,ʾAhl ūs-Sunnah wa āl-Ǧamāʿah,简称أهل السنة ʾAhl ūs-Sunnah),又译素尼派,原意为遵循圣训者,为伊斯兰教中的最大派别,自称“正统派”,与什叶派对立。一般认为,全世界大约有85~91%穆斯林隶属此派别[1][2][3]。

スンナ派(アラビア語:(أهل السنة (والجماعة 、ラテン文字転写:Ahl as-Sunnah (wa’l-Jamā‘ah))、あるいはスンニ派(日本では報道などでこちらが一般的に知られる)は、イスラム教(イスラーム)の二大宗派のひとつとされる。他のひとつはシーア派である。イスラームの各宗派間では、最大の勢力、多数派を形成する。

Sunni Islam (/ˈsuːni, ˈsʊni/) is the largest denomination of Islam, followed by 87–90% of the world's Muslims, characterized by a greater emphasis upon the prophet, the sahabah (in particular the Rashidun), and customs deduced thereof.[1][2] Its name comes from the word sunnah, referring to the behaviour of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[3] The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagreement over the succession to Muhammad and subsequently acquired broader political significance, as well as theological and juridical dimensions.[4]

According to Sunni traditions, Muhammad did not clearly designate a successor and the Muslim community acted according to his sunnah in electing his father-in-law Abu Bakr as the first caliph.[4] This contrasts with the Shia view, which holds that Muhammad announced his son-in-law and cousin Ali ibn Abi Talib as his successor, most notably at Ghadir Khumm.[5][6][7][8][9] Political tensions between Sunnis and Shias continued with varying intensity throughout Islamic history and have been exacerbated in recent times by ethnic conflicts and the rise of Wahhabism.[4]

The adherents of Sunni Islam are referred to in Arabic as ahl as-sunnah wa l-jamāʻah ("the people of the sunnah and the community") or ahl as-sunnah for short.[10][11] In English, its doctrines and practices are sometimes called Sunnism,[12] while adherents are known as Sunni Muslims, Sunnis, Sunnites and Ahlus Sunnah. Sunni Islam is sometimes referred to as "orthodox Islam",[13][14][15] though some scholars view this translation as inappropriate.[16]

The Quran, together with hadith (especially those collected in Kutub al-Sittah) and binding juristic consensus, form the basis of all traditional jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. Sharia rulings are derived from these basic sources, in conjunction with analogical reasoning, consideration of public welfare and juristic discretion, using the principles of jurisprudence developed by the traditional legal schools. In matters of creed, the Sunni tradition upholds the six pillars of iman (faith) and comprises the Ash'ari and Maturidi schools of rationalistic theology as well as the textualist school known as traditionalist theology. Sunni Islam is not a coherent line of tradition, but a consolidation of doctrines and positions worked out over time in discussions and writings.[17]

Le sunnisme1 est le principal courant religieux de l'islam représentant 90 % des musulmans du monde2. Constituant l'un des trois grands courants de l'islam avec le chiisme et le kharidjisme, le sunnisme se distingue des autres courants de l'islam par son interprétation de la religion. Les sunnites sont désignés en arabe comme les gens de la « sunna » et de la majorité religieuse (ahl al-sunna wa'l-djama‘a). Par opposition aux chiites et aux kharidjites, on les appelle parfois « musulmans orthodoxes »3.

Il sunnismo (in arabo: أهل السنة والجماعة, ahl al-sunna wa l-jamāʿa[1], "il popolo della Sunna e della Comunità") è la corrente maggioritaria dell'Islam, comprendendo circa l'85% dell'intero mondo islamico[2]. Essa riconosce la validità della Sunna (consuetudine[3], identificata coi Sei libri) e si ritiene erede della giusta interpretazione del Corano[1], articolata giuridicamente in 4 scuole o madhhab. Queste si dividono in Hanafismo, Malikismo, Sciafeismo, Hanbalismo. Mentre il cristianesimo è la maggiore religione del mondo (con 2,1 miliardi di aderenti) e l'Islam la seconda (con 1,8 miliardi), come confessioni il sunnismo (1,6 miliardi) supera il cattolicesimo (1,2 miliardi). Nell'islam, oltre al sunnismo, le principali confessioni sono rappresentate dallo Sciismo e dal Kharigismo. Sono presenti inoltre numerose forme minori (vedi denominazioni islamiche).

Nel sunnismo, così come nelle altre confessioni islamiche, ci sono divisioni interne tra i credenti sufi e coloro che rifiutano l'approccio sufico.

Los suníes1(en idioma árabe, سنّة) ʾAhlu-s-Sunnati wa-l-Jamāʿah (en árabe, أهل السنة والجماعة) son el grupo musulmán mayoritario en la comunidad islámica mundial. Su nombre procede del hecho de que, además del Corán, son devotos de la Sunna, colección de dichos y hechos atribuidos al profeta Mahoma. Aunque el Islam sunita se compone de una variedad de escuelas teológicas y legales que se desarrollaron a través de entornos históricos, localidades y culturas, los sunitas de todo el mundo comparten algunas creencias comunes: la aceptación de la legitimidad de los primeros cuatro sucesores del profeta Mahoma (Abu Bakr, Omar , Uthman y Ali), y la creencia de que otras sectas islámicas han introducido innovaciones (bidah), partiendo de la creencia mayoritaria.

Sunni Islam se desarrolló a partir de las luchas en el Islam temprano sobre el liderazgo. Las posiciones políticas y religiosas surgieron de las disputas sobre la definición de la creencia "verdadera", la libertad y el determinismo. Los sunitas tienden a rechazar el racionalismo excesivo o el intelectualismo en cuestiones de credo, centrándose en el espíritu y la intención de las fuentes primarias y utilizando argumentos racionales, cuando sea necesario, para defender la ortodoxia y refutar la herejía.23

Сунни́ты, ахль ас-су́нна ва-ль-джама‘а (от араб. أهل السنة والجماعة — «люди сунны и согласия общины») — последователи основного и наиболее многочисленного направления в исламе.

Egypt

Egypt

Australia

Australia

Belgium

Belgium

Brunei Darussalam

Brunei Darussalam

China

China

Germany

Germany

Djibouti

Djibouti

France

France

Greece

Greece

Guangdong Sheng-GD

Guangdong Sheng-GD

Hongkong Tebiexingzhengqu-HK

Hongkong Tebiexingzhengqu-HK

India

India

Indonesia

Indonesia

IT-Times

IT-Times

Late Classical, Romantic (Early, Middle, Late)

Late Classical, Romantic (Early, Middle, Late)

Italy

Italy

Japan

Japan

Malaysia

Malaysia

Morocco

Morocco

Myanmar

Myanmar

Oman

Oman

Pakistan

Pakistan

Philippines

Philippines

Portugal

Portugal

Republic of Korea

Republic of Korea

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

Shanghai Shi-SH

Shanghai Shi-SH

Singapore

Singapore

Singapore

Singapore

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

Taiwan Sheng-TW

Taiwan Sheng-TW

Thailand

Thailand

Turkey

Turkey

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Vietnam

Vietnam

Cyprus

Cyprus

Afghanistan

Afghanistan

Egypt

Egypt

Armenia

Armenia

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan

Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Australia

Australia

Bangladesh

Bangladesh

Beijing Shi-BJ

Beijing Shi-BJ

Brunei Darussalam

Brunei Darussalam

China

China

Denmark

Denmark

Demokratische Republik Timor-Leste

Demokratische Republik Timor-Leste

Germany

Germany

Fidschi

Fidschi

Financial

Financial

International Bank for Cooperation

International Bank for Cooperation

Finland

Finland

France

France

Georgia

Georgia

Hongkong Tebiexingzhengqu-HK

Hongkong Tebiexingzhengqu-HK

India

India

Indonesia

Indonesia

Iran

Iran

Ireland

Ireland

Iceland

Iceland

Israel

Israel

Italy

Italy

Jordan

Jordan

Cambodia

Cambodia

Kasachstan

Kasachstan

Katar

Katar

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan

Laos

Laos

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Malaysia

Malaysia

Malediven

Malediven

Malta

Malta

Mongolei

Mongolei

Myanmar

Myanmar

Nepal

Nepal

New Zealand

New Zealand

Netherlands

Netherlands

Norwegen

Norwegen

Oman

Oman

Austria

Austria

Pakistan

Pakistan

Philippines

Philippines

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Republic of Korea

Republic of Korea

Russia

Russia

Samoa

Samoa

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland

Singapore

Singapore

Spain

Spain

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

South Africa

South Africa

Tajikistan

Tajikistan

Thailand

Thailand

Turkey

Turkey

Hungary

Hungary

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Vietnam

Vietnam

Important International Organizations

Important International Organizations

Economy and trade

Economy and trade

Economic and political research

Economic and political research

Cyprus

Cyprus

Anlass zur Initiative der Gründung war insbesondere die Unzufriedenheit Chinas über eine Dominanz der US-Amerikaner im Internationalen Währungsfonds, der keine faire Verteilung der globalen Machtverhältnisse aus Sicht Chinas widerspiegelte.[2] Da sich die US-Amerikaner strikt weigerten, eine Änderung der Stimmverhältnisse zu implementieren, begann China 2013 mit der Gründung der Initiative. Neben den 21 Gründungsmitgliedern haben im Jahr 2015 auch unter anderem Deutschland, Italien, Frankreich und das Vereinigte Königreich ihr Interesse bekundet, als nicht-regionale Mitglieder die neue Entwicklungsbank zu unterstützen.[3]

Die Gründungsurkunde der AIIB wurde am 29. Juni 2015 von Vertretern aus 57 Ländern in Peking unterzeichnet.[4] Die Bank nahm im Januar 2016 ihre Arbeit ohne Beteiligung der USA und Japan auf.[5]

Joachim von Amsberg ist der "Vizepräsident für Politik und Strategie".

亚洲基础设施投资银行(英语:Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank,縮寫:AIIB),简称亚投行,是一个愿意向亚洲国家和地區的基础设施建设提供资金支持的政府间性质的亚洲区域多边开发机构,成立的目的是促进亚洲区域的互联互通建设和经济一体化的进程,並且加大中國與其他亚洲國家和地区的合作力度。总部设在中国北京,法定资本为1,000亿美元。[2]

中华人民共和国主席习近平于2013年10月2日在雅加达同印度尼西亚总统苏西洛举行会谈时首次倡议筹建亚投行。[3]2014年10月24日,中国、印度、新加坡等21国在北京正式签署《筹建亚投行备忘录》。[2]2014年11月25日,印度尼西亚签署备忘录,成为亚投行第22个意向创始成员国。[4]

2015年3月12日,英国正式申请作为意向创始成员国加入亚投行,[5]成为正式申请加入亚投行的首个欧洲国家、主要西方国家。[6]随后法国、意大利、德国等西方国家纷纷以意向创始成员国身份申请加入亚投行。[7]接收新意向创始成员国申请截止日期3月31日临近,韩国[8]、俄罗斯[9]、巴西[10]等域内国家和重要新兴经济体也抓紧申请成为亚投行意向创始成员国。

各方商定将于2015年年中完成亚投行章程谈判并签署,年底前完成章程生效程序,正式成立亚投行。[11]

アジアインフラ投資銀行(アジアインフラとうしぎんこう、英: Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, AIIB、中: 亚洲基础设施投资银行,亞洲基礎設施投資銀行)は、国際開発金融機関のひとつである。

中華人民共和国が2013年秋に提唱し主導する形で発足した[1]。「合計の出資比率が50%以上となる10以上の国が国内手続きを終える」としていた設立協定が発効条件を満たし、2015年12月25日に発足し[2][3]、2016年1月16日に開業式典を行った[1][4]。

57か国を創設メンバーとして発足し[1][5]、2017年3月23日に加盟国は70カ国・地域となってアジア開発銀行の67カ国・地域を超え[6][7]、一方で日本、アメリカ合衆国などは2017年の現時点で参加を見送っている[8]。 創設時の資本金は1000億ドルである[9]。

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) is a multilateral development bank that aims to support the building of infrastructure in the Asia-Pacific region. The bank currently has 93 members from around the world [7]. The bank started operation after the agreement entered into force on 25 December 2015, after ratifications were received from 10 member states holding a total number of 50% of the initial subscriptions of the Authorized Capital Stock.[8]

The United Nations has addressed the launch of AIIB as having potential for "scaling up financing for sustainable development"[9] and to improve the global economic governance.[10] The starting capital of the bank was $100 billion, equivalent to 2⁄3 of the capital of the Asian Development Bank and about half that of the World Bank.[11]

The bank was proposed by China in 2013[12] and the initiative was launched at a ceremony in Beijing in October 2014.[13] It received the highest credit ratings from the three biggest rating agencies in the world, and is seen as a potential rival to the World Bank and IMF.[14][15]

La Banque asiatique d'investissement dans les infrastructures (BAII ou AIIB), est une banque d'investissement proposée par la République populaire de Chine dans le but de concurrencer le Fonds monétaire international, la Banque mondiale et la Banque asiatique de développement1 pour répondre au besoin croissant d'infrastructures en Asie du Sud-Est et en Asie centrale. Cette banque s'inscrit dans la stratégie de la nouvelle route de la soie, développée par la Chine.

La Banca Asiatica d'Investimento per le infrastrutture (AIIB), fondata a Pechino nell'ottobre 2014, è un'istituzione finanziaria internazionale proposta dalla Repubblica Popolare Cinese. Si contrappone al Fondo Monetario Internazionale, alla Banca Mondiale e all'Asian Development Bank[1], le quali si trovano sotto il controllo del capitale e delle scelte strategiche dei paesi sviluppati come gli Stati Uniti d'America.[2] Scopo della Banca è fornire e sviluppare progetti di infrastrutture nella regione Asia-Pacifico attraverso la promozione dello sviluppo economico-sociale della regione e contribuendo alla crescita mondiale.

El Banco Asiático de Inversión en Infraestructura (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank o AIIB) es una institución financiera internacional propuesta por el gobierno de China. El propósito de este banco de desarrollo multilateral es proporcionar la financiación para proyectos de infraestructura en la región de Asia basado en un sistema financiero de préstamo1 y el fomento del sistema de libre mercado en los países asiáticos.

El AIIB está considerado por algunos como una versión continental del FMI y del Banco Mundial, y busca ser un rival por la influencia en la región del Banco de Desarrollo asiático (ADB), el cual esta alineado a los intereses de potencias, tanto regionales (Japón), como globales (Estados Unidos, la Unión Europea).2

El banco fue propuesto por Xi Jinping en 2013 e inaugurado con una ceremonia en Pekín en octubre de 2014. La ONU se a mostrado entusiasta con la propuesta china, a la que a descrito como el FMI del futuro y a señalado como "una gran propuesta para financiar el desarrollo sostenible" y "mejorar la gobernanza económica mundial". La entidad constó inicialmente con 100 mil millones de dolares, es decir, la mitad del dinero de que posee el Banco Mundial.

La entidad a recibido inversión por parte de corporaciones financieras estadounidenses como la Standard & Poor's, Moody's o Fitch Group34. Actualmente la entidad consta de 87 miembros, incluyendo los 57 miembros fundadores. Bélgica, Canadá, y Ucrania están barajando unirse al AIIB. Estados Unidos, Japón y Colombia no tienen intención de participar. China a prohibido a Corea del Norte unirse, instigando además una política de aislamiento contra esta por parte del AIIB.

Азиатский банк инфраструктурных инвестиций (АБИИ) (англ. Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, AIIB) — международная финансовая организация, создание которой было предложено Китаем. Основные цели, которые преследует АБИИ, — стимулирование финансового сотрудничества в Азиатско-Тихоокеанском регионе, финансирование инфраструктурных проектов в Азии от строительства дорог и аэропортов до антенн связи и жилья экономкласса[1].

По заявлениям вице-премьера России Игоря Шувалова, AБИИ не рассматривается как потенциальный конкурент МВФ, Всемирного банка и Азиатского банка развития (АБР). Однако эксперты рассматривают AIIB как потенциального конкурента базирующихся в США Международного валютного фонда (МВФ) и Всемирного банка. После сообщений об успехах AIIB американский министр финансов США Джейкоб Лью предупредил, что международным финансовым организациям в США, таким как ВБ и МВФ, грозит потеря доверия [2][3].

Китай, Индия и Россия возглавили организацию, оказавшись в тройке крупнейших владельцев голосов. При этом на важнейшие решения КНР имеет фактическое право вето[4].

Afghanistan

Afghanistan

Egypt

Egypt

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan

Bahrain

Bahrain

China

China

Hand in Hand

Hand in Hand

India

India

Iraq

Iraq

Iran

Iran

Israel

Israel

Jordan

Jordan

Cambodia

Cambodia

Kasachstan

Kasachstan

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan

Mongolei

Mongolei

Pakistan

Pakistan

Palestine

Palestine

Republic of Korea

Republic of Korea

Russia

Russia

Tajikistan

Tajikistan

Thailand

Thailand

Turkey

Turkey

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates

Vietnam

Vietnam

Geography

Geography

Literature

Literature

Sport

Sport

Automobile

Automobile

Companies

Companies

Architecture

Architecture

Museum

Museum

World Heritage

World Heritage

Ski vacation

Ski vacation

Transport and traffic

Transport and traffic

Party and government

Party and government