Deutsch-Chinesische Enzyklopädie, 德汉百科

Jilin Sheng-JL

Jilin Sheng-JL

Beijing Shi-BJ

Beijing Shi-BJ

Belarus

Belarus

Berlin

Berlin

Brandenburg

Brandenburg

Bremen

Bremen

China

China

Germany

Germany

France

France

Gansu Sheng-GS

Gansu Sheng-GS

Hamburg

Hamburg

Hebei Sheng-HE

Hebei Sheng-HE

Heilongjiang Sheng-HL

Heilongjiang Sheng-HL

Henan Sheng-HA

Henan Sheng-HA

Hubei Sheng-HB

Hubei Sheng-HB

Hunan Sheng-HN

Hunan Sheng-HN

Iran

Iran

Italy

Italy

Jilin Sheng-JL

Jilin Sheng-JL

Kasachstan

Kasachstan

Liaoning Sheng-LN

Liaoning Sheng-LN

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Netherlands

Netherlands

Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

North Rhine-Westphalia

North Rhine-Westphalia

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Russia

Russia

Saxony

Saxony

Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shandong Sheng-SD

Shandong Sheng-SD

Shanxi Sheng-SX

Shanxi Sheng-SX

Sichuan Sheng-SC

Sichuan Sheng-SC

Spain

Spain

Turkey

Turkey

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

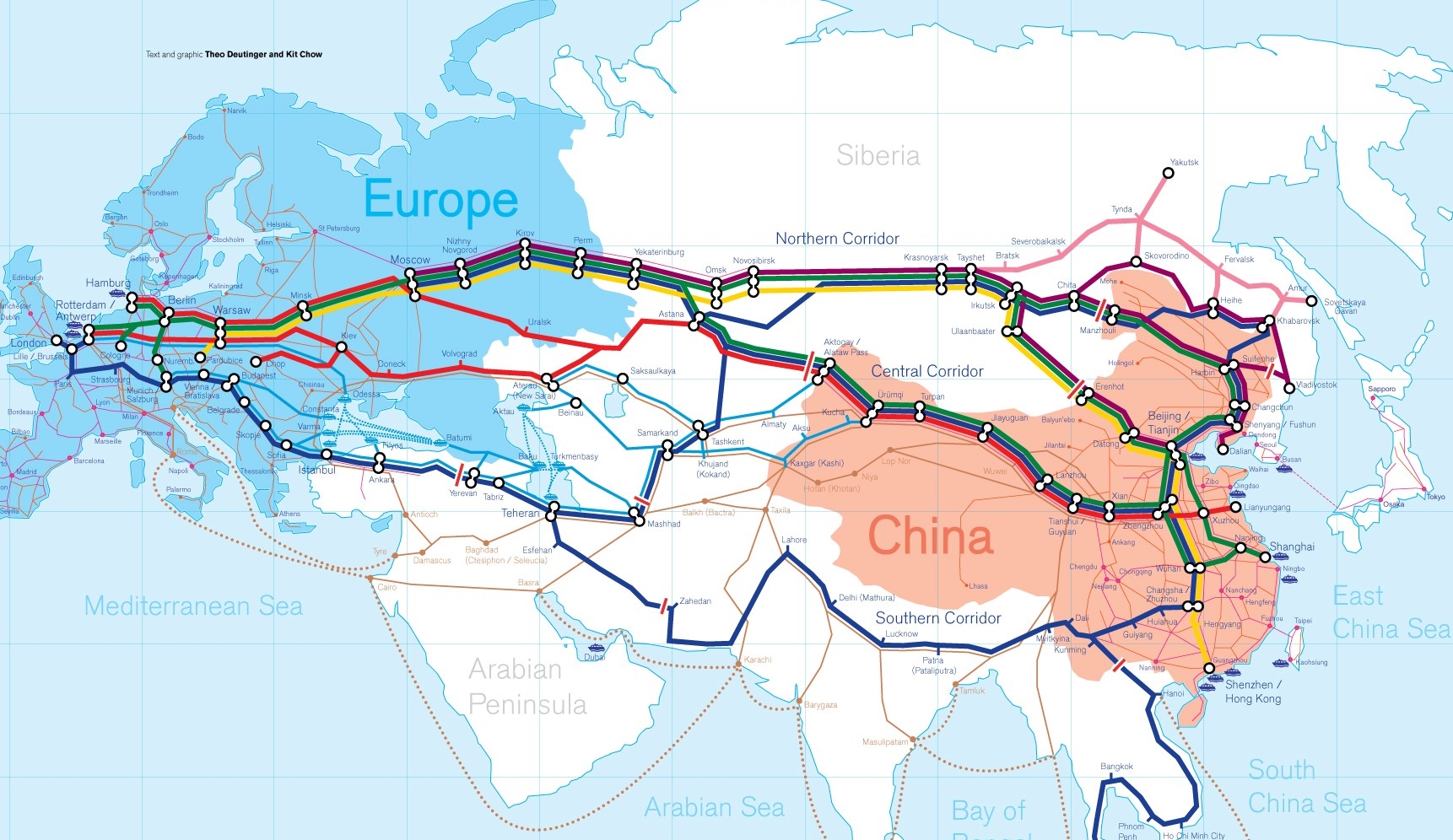

Die Neue eurasische Kontinentalbrücke (chinesisch 新亚欧大陆桥, Pinyin Xīn Yà-Ōu Dàlù Qiáo, englisch New Eurasian Continental Bridge), die auch Zweite eurasische Kontinentalbrücke (第二亚欧大陆桥, Dì'èr Yà-Ōu Dàlù Qiáo, englisch Second Eurasian Continental Bridge) genannt wird, ist eine 10.870 Kilometer[1] lange Eisenbahnverbindung, die Rotterdam in Europa mit der ostchinesischen Hafenstadt Lianyungang in der Provinz Jiangsu verbindet.

Sie besteht seit 1990 und führt durch die Dsungarische Pforte (Grenzbahnhof Alashankou). Die Lan-Xin-Bahn (chinesisch 兰新铁路, Pinyin Lán-Xīn Tiělù), also die Strecke von Lanzhou nach Ürümqi (in Xinjiang), ist ein Teil von ihr.

Es gibt eine nördliche, mittlere und südliche Route.[2] Die mittlere Strecke verläuft durch Kasachstan über Dostyk, Aqtogai, Astana, Samara, Smolensk, Brest, Warschau, Berlin zum Hafen von Rotterdam.[3] Vom slowakischen Košice soll auch eine Abzweigung in den Großraum Wien führen, siehe Breitspurstrecke Košice–Wien.

The New Eurasian Land Bridge, also called the Second or New Eurasian Continental Bridge, is the southern branch of the Eurasian Land Bridge rail links running through China. The Eurasian Land Bridge is the overland rail link between Asia and Europe.

Due to a break-of-gauge between standard gauge used in China and the Russian gauge used in the former Soviet Union countries, containers must be physically transferred from Chinese to Kazakh railway cars at Dostyk on the Chinese-Kazakh border and again at the Belarus-Poland border where the standard gauge used in western Europe begins. This is done with truck-mounted cranes.[1] Chinese media often states that the New Eurasian Land/Continental Bridge extends from Lianyungang to Rotterdam, a distance of 11,870 kilometres (7,380 mi). The exact route used to connect the two cities is not always specified in Chinese media reports, but appears to usually refer to the route which passes through Kazakhstan.

All rail freight from China across the Eurasian Land Bridge must pass north of the Caspian Sea through Russia at some point. A proposed alternative would pass through Turkey and Bulgaria,[2] but any route south of the Caspian Sea must pass through Iran.[1]

Kazakhstan's President Nursultan Nazarbayev urged Eurasian and Chinese leaders at the 18th Shanghai Cooperation Organisation to construct the Eurasian high-speed railway (EHSRW) following a Beijing-Astana-Moscow-Berlin.[3]

The Eurasian Land Bridge (Russian: Евразийский сухопутный мост, Yevraziyskiy sukhoputniy most), sometimes called the New Silk Road (Новый шёлковый путь, Noviy shyolkoviy put'), or Belt and Road Initiative is the rail transport route for moving freight and passengers overland between Pacific seaports in the Russian Far East and China and seaports in Europe. The route, a transcontinental railroad and rail land bridge, currently comprises the Trans-Siberian Railway, which runs through Russia and is sometimes called the Northern East-West Corridor, and the New Eurasian Land Bridge or Second Eurasian Continental Bridge, running through China and Kazakhstan. As of November 2007, about 1% of the $600 billion in goods shipped from Asia to Europe each year were delivered by inland transport routes.[1]

Completed in 1916, the Trans-Siberian connects Moscow with Russian Pacific seaports such as Vladivostok. From the 1960s until the early 1990s the railway served as the primary land bridge between Asia and Europe, until several factors caused the use of the railway for transcontinental freight to dwindle. One factor is that the railways of the former Soviet Union use a wider rail gauge than most of the rest of Europe as well as China. Recently, however, the Trans-Siberian has regained ground as a viable land route between the two continents.[why?]

China's rail system had long linked to the Trans-Siberian via northeastern China and Mongolia. In 1990 China added a link between its rail system and the Trans-Siberian via Kazakhstan. China calls its uninterrupted rail link between the port city of Lianyungang and Kazakhstan the New Eurasian Land Bridge or Second Eurasian Continental Bridge. In addition to Kazakhstan, the railways connect with other countries in Central Asia and the Middle East, including Iran. With the October 2013 completion of the rail link across the Bosphorus under the Marmaray project the New Eurasian Land Bridge now theoretically connects to Europe via Central and South Asia.

Proposed expansion of the Eurasian Land Bridge includes construction of a railway across Kazakhstan that is the same gauge as Chinese railways, rail links to India, Burma, Thailand, Malaysia and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, construction of a rail tunnel and highway bridge across the Bering Strait to connect the Trans-Siberian to the North American rail system, and construction of a rail tunnel between South Korea and Japan. The United Nations has proposed further expansion of the Eurasian Land Bridge, including the Trans-Asian Railway project.

El Nuevo Puente de Tierra de Eurasia es también llamado el Segundo o Nuevo Puente Continental de Eurasia. Es la rama meridional de las conexiones ferroviarias del Puente de Tierra de Eurasia (también conocido como "Nueva Ruta de la Seda") que se extienden a través de la República Popular China, atravesando Kazajistán, Rusia y Bielorrusia. El Puente de Tierra de Eurasia es el enlace ferroviario terrestre entre Asia Oriental y Europa.

La Nueva Ruta de la Seda (en ruso, Новый шёлковый путь, Noviy shyolkoviy put), o Puente Terrestre Euroasiático, es la ruta de transporte ferroviario para el movimiento de tren de mercancías y tren de pasajeros por tierra entre los puertos del Pacífico, en el Lejano Oriente ruso y chino y los puertos marítimos en Europa.

La ruta, un ferrocarril transcontinental y puente terrestre, actualmente comprende el ferrocarril Transiberiano, que se extiende a través de Rusia, y el nuevo puente de tierra de Eurasia o segundo puente continental de Eurasia, que discurre a través de China y Kazajistán, también se van a construir carreteras entre las ciudades de la ruta. A partir de noviembre de 2007, aproximadamente el 1% de los 600 millones de dólares en bienes enviados desde Asia a Europa cada año se entregaron por vías de transporte terrestre.1

Terminado en 1916, el tren Transiberiano conecta Moscú con el lejano puerto de Vladivostok en el océano Pacífico, el más largo del mundo en el Lejano Oriente e importante puerto del Pacífico. Desde la década de 1960 hasta principios de 1990 el ferrocarril sirvió como el principal puente terrestre entre Asia y Europa, hasta que varios factores hicieron que el uso de la vía férrea transcontinental para el transporte de carga disminuyese.

Un factor es que los ferrocarriles de la Unión Soviética utilizan un ancho de vía más ancho en los rieles que la mayor parte del resto de Europa y China, y el transporte en barcos de carga por el canal de Suez en Egipto, construido por Inglaterra. El sistema ferroviario de China se une al Transiberiano en el noreste de China y Mongolia. En 1990 China añadió un enlace entre su sistema ferroviario y el Transiberiano a través de Kazajistán. China denomina a su enlace ferroviario ininterrumpido entre la ciudad portuaria de Lianyungang y Kazajistán como el «Puente terrestre de Nueva Eurasia» o «Segundo puente continental Euroasiático». Además de Kazajistán, los ferrocarriles conectan con otros países de Asia Central y Oriente Medio, incluyendo a Irán. Con la finalización en octubre de 2013 de la línea ferroviaria a través del Bósforo en el marco del proyecto Marmaray el puente de tierra de Nueva Eurasia conecta ahora teóricamente a Europa a través de Asia Central y del Sur.

La propuesta de ampliación del Puente Terrestre Euroasiático incluye la construcción de un ferrocarril a través de Kazajistán con el mismo ancho de vía que los ferrocarriles chinos, enlaces ferroviarios a la India, Birmania, Tailandia, Malasia y otros países del sudeste asiático, la construcción de un túnel ferroviario y un puente de carretera a través del estrecho de Bering para conectar el Transiberiano al sistema ferroviario de América del Norte, y la construcción de un túnel ferroviario entre Corea del Sur y Japón. Las Naciones Unidas ha propuesto una mayor expansión del Puente Terrestre Euroasiático, incluyendo el proyecto del ferrocarril transasiático.

Новый шёлковый путь (Евразийский сухопутный мост — концепция новой паневразийской (в перспективе — межконтинентальной) транспортной системы, продвигаемой Китаем, в сотрудничестве с Казахстаном, Россией и другими странами, для перемещения грузов и пассажиров по суше из Китая в страны Европы. Транспортный маршрут включает трансконтинентальную железную дорогу — Транссибирскую магистраль, которая проходит через Россию и второй Евразийский континентальный мост[en], проходящий через Казахстан[1]. Поезда по этому самому длинному в мире грузовому железнодорожному маршруту из Китая в Германию будут идти 15 дней, что в 2 раза быстрее, чем по морскому маршруту через Суэцкий канал[2].

Идея Нового шёлкового пути основывается на историческом примере древнего Великого шёлкового пути, действовавшего со II в. до н. э. и бывшего одним из важнейших торговых маршрутов в древности и в средние века. Современный НШП является важнейшей частью стратегии развития Китая в современном мире — Новый шёлковый путь не только должен выстроить самые удобные и быстрые транзитные маршруты через центр Евразии, но и усилить экономическое развитие внутренних регионов Китая и соседних стран, а также создать новые рынки для китайских товаров (по состоянию на ноябрь 2007 года, около 1 % от товаров на 600 млрд долл. из Азии в Европу ежегодно доставлялись наземным транспортом[3]).

Китай продвигает проект «Нового шёлкового пути» не просто как возрождение древнего Шёлкового пути, транспортного маршрута между Востоком и Западом, но как масштабное преобразование всей торгово-экономической модели Евразии, и в первую очередь — Центральной и Средней Азии. Китайцы называют эту концепцию — «один пояс — один путь». Она включает в себя множество инфраструктурных проектов, которые должны в итоге опоясать всю планету. Проект всемирной системы транспортных коридоров соединяет Австралию и Индонезию, всю Центральную и Восточную Азию, Ближний Восток, Европу, Африку и через Латинскую Америку выходит к США. Среди проектов в рамках НШП планируются железные дороги и шоссе, морские и воздушные пути, трубопроводы и линии электропередач, и вся сопутствующая инфраструктура. По самым скромным оценкам, НШП втянет в свою орбиту 4,4 миллиарда человек — более половины населения Земли[4].

Предполагаемое расширение Евразийского сухопутного моста включает в себя строительство железнодорожных путей от трансконтинентальных линий в Иран, Индию, Мьянму, Таиланд, Пакистан, Непал, Афганистан и Малайзию, в другие регионы Юго-Восточной Азии и Закавказья (Азербайджан, Грузия). Маршрут включает тоннель Мармарай под проливом Босфор, паромные переправы через Каспийское море (Азербайджан-Иран-Туркменистан-Казахстан) и коридор Север-Юг.Организация Объединенных Наций предложила дальнейшее расширение Евразийского сухопутного моста, в том числе проекта Трансазиатской железной дороги (фактически существует уже в 2 вариантах).

Для развития инфраструктурных проектов в странах вдоль Нового шёлкового пути и Морского Шёлкового пути и с целью содействия сбыту китайской продукции в декабре 2014 года был создан инвестиционный Фонд Шёлкового пути[5].

8 мая 2015 года было подписано совместное заявление Президента РФ В. Путина и Председателя КНР Си Цзиньпина о сотрудничестве России и Китая, в рамках ЕАЭС и трансевразийского торгово-инфраструктурного проекта экономического пояса «Шёлковый путь». 13 июня 2015 года был запущен самый длинный в мире грузовой железнодорожный маршрут Харбин — Гамбург (Германия), через территорию России.

萨满是分布于北美洲和北亚、中亚一类巫觋宗敎,包括满族萨满、蒙古族萨满、中亚萨满、西伯利亚萨满、北美洲萨满。萨满(珊蛮)曾被认为有控制天气、预言、解梦、占星以及旅行到天堂或者地狱的能力。萨满目前最盛行于美国,美音美洲的原住民(尤其是北美洲)非常相信,即使是被基督教的美国征服以后。在亚洲的传统始于史前时代并且遍布世界。最崇拜萨满的地方是伏尔加河流域、芬兰人种居住的地区、东西伯利亚与西西伯利亚。满洲人的祖先女真人,也曾信奉萨满,直到公元11世纪。[1]清代以前一直在中国东北甚至蒙古地区大范围流传,清朝皇帝把萨满和满族的传统结合起来,运用萨满把东北的人民纳入帝国的轨道,同时萨满在清朝的宫廷生活中也找到了位置。目前,满族、鄂温克族等民族有很多信奉萨满的人群,并且有萨满。

Schamanismus bezeichnet:

- Im engen Sinne die traditionellen ethnischen Religionen des Kulturareales Sibirien (Nenzen, Jakuten, Altaier, Burjaten, Ewenken, auch europäische Samen u. a.), bei denen das Vorhandensein von Schamanen von europäischen Forschern der Expansionszeit als wesentliches gemeinsames Kennzeichen erachtet wurde.[1] Zur besseren Abgrenzung werden diese Religionen häufig „klassischer Schamanismus“ oder auch „sibirischer Animismus“ genannt.[2]

- Im weiten Sinne alle wissenschaftlichen Konzepte, die aufgrund von ähnlichen Praktiken spiritueller Spezialisten in verschiedenen traditionellen Gesellschaften die kulturübergreifende Existenz des Schamanismus postulieren. Nach László Vajda[3] und Jane Monnig Atkinson[A 1] sollte aufgrund der Vielzahl unterschiedlicher Konzepte treffender von Schamanismen im Plural gesprochen werden.

Sibirische Schamanen und verschiedene Geisterbeschwörer anderer Ethnien – die ebenfalls häufig verallgemeinernd als Schamanen bezeichnet werden – hatten oder haben in vielen traditionellen Weltanschauungen angeblich Einfluss auf die Mächte des Jenseits. Sie setzten ihre Fähigkeiten vorwiegend zum Wohle der Gemeinschaft ein, um in unlösbar erscheinenden Krisensituationen die „kosmische Harmonie“ zwischen Diesseits und Jenseits wiederherzustellen. In diesem weiten Sinne bezeichnet Schamanismus eine Reihe unscharf bestimmter Phänomene „zwischen Religion und Heilritual“.[4][5][6][7][8][9][Anmerkung 1]

Eine nähere allgemeingültige Bestimmung ist nicht möglich, da die Definition verschiedene Betrachtungsweisen aus Sicht der Ethnologie, Kulturanthropologie, Religionswissenschaften, Archäologie, Soziologie und Psychologie enthält.[10][11] Dies hat unter anderem zur Folge, dass Angaben zur räumlichen und zeitlichen Verbreitung der „Schamanismen“ erheblich voneinander abweichen und in vielen Fällen umstritten sind.[12][13][14] Der amerikanische Ethnologe Clifford Geertz sprach daher bereits in den 1960er Jahren dem „westlich idealistischen Konstrukt Schamanismus“ jeglichen Erklärungswert ab.[A 2]

Einig ist man sich lediglich bei der „engen Definition“ des klassisch sibirischen Schamanismus – dem Ausgangspunkt der ersten „Schamanismen“. Dazu gehört vor allem die genaue Beschreibung der dort praktizierten rituellen Ekstase, eine weitgehend übereinstimmende ethnische Religion sowie eine ähnliche Kosmologie und Lebensweise.[15][11][16]

Nach weiter gefassten Definitionen wird Schamanismus bis in die 1980er Jahre als frühe, kulturübergreifende Entwicklungsstufe jeglicher Religion betrachtet.[15] Vor allem das Konzept des Core-Schamanismus von Michael Harner ist hier zu nennen. Diese Auslegung gilt jedoch mittlerweile als nicht konsensfähig.[14] Seit den 1990er Jahren steht häufig der Aspekt des „Heilens“ im Mittelpunkt des Interesses (und der jeweiligen Definition).[10]

Da bereits der klassische Schamanismus Sibiriens etliche Varianten aufweist, werden weiter reichende geographische oder historische Auslegungen, die solche Phänomene aus ihrem kulturellen Kontext gelöst betrachten und verallgemeinern, von vielen Autoren als spekulativ kritisiert.[17][13] In der zeitgenössischen Literatur – populärwissenschaftlichen (insbesondere esoterischen) Büchern, aber auch wissenschaftlichen Schriften – wird in diesem Zusammenhang oftmals nicht deutlich gemacht, auf welche Ethnien sich Darstellungen zu bestimmten schamanischen Praktiken konkret beziehen, so dass regionale (oft sibirische) Phänomene auch in anderen Kulturen verortet werden, in deren Traditionen sie tatsächlich jedoch fremd sind. Beispiele dafür sind der Weltenbaum und die gesamte schamanische Kosmologie: in Eurasien verankerte mythologische Konzepte, die hier mit ähnlichen Archetypen anderer Weltgegenden gleichgesetzt werden und so das irreführende Bild eines einheitlichen Schamanismus erzeugen.[13]

Insbesondere die äußerst erfolgreichen Bücher von Eliade, Castañeda und Harner haben den „modernen Mythos Schamanismus“ erzeugt, der suggeriert, dass es sich dabei um ein universelles und homolog entstandenes religiös-spirituelles Phänomen handeln würde. Im Hinblick auf das große Interesse in der Bevölkerung[18] weisen einige Autoren darauf hin, dass Schamanismus keine einheitliche Ideologie oder Religion bestimmter Kulturen ist, sondern um ein wissenschaftliches Konstrukt aus eurozentrischer Perspektive handelt, um ähnliche Phänomene rund um die Geisterbeschwörer unterschiedlichster Herkunft zu vergleichen und zu klassifizieren.[14][19][20]

シャーマニズムあるいはシャマニズム(英: Shamanism)とは、シャーマン(巫師・祈祷師)の能力により成立している宗教や宗教現象の総称であり[1]、宗教学、民俗学、人類学(宗教人類学、文化人類学)等々で用いられている用語・概念である[1]。巫術(ふじゅつ)などと表記されることもある[1]。

シャーマニズムとはシャーマンを中心とする宗教形態で、精霊や冥界の存在が信じられている。シャーマニズムの考えでは、霊の世界は物質界よりも上位にあり、物質界に影響を与えているとされる[2]。

シャーマンとはトランス状態に入って超自然的存在(霊、神霊、精霊、死霊など)と交信する現象を起こすとされる職能・人物のことである[1]。 「シャーマン」という用語・概念は、ツングース語で呪術師の一種を指す「šaman, シャマン」に由来し[1][注釈 1]、19世紀以降に民俗学者や旅行家、探検家たちによって、極北や北アジアの呪術あるいは宗教的職能者一般を呼ぶために用いられるようになり、その後に宗教学、民俗学、人類学などの学問領域でも類似現象を指すための用語(学術用語)として用いられるようになったものである[1]。

Shamanism is a practice that involves a practitioner reaching altered states of consciousness in order to perceive and interact with what they believe to be a spirit world and channel these transcendental energies into this world.[1]

A shaman (/ˈʃɑːmən/ SHAH-men, /ˈʃæmən/ or /ˈʃeɪmən/)[2] is someone who is regarded as having access to, and influence in, the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits, who typically enters into a trance state during a ritual, and practices divination and healing.[2] The word "shaman" probably originates from the Tungusic Evenki language of North Asia. According to ethnolinguist Juha Janhunen, "the word is attested in all of the Tungusic idioms" such as Negidal, Lamut, Udehe/Orochi, Nanai, Ilcha, Orok, Manchu and Ulcha, and "nothing seems to contradict the assumption that the meaning 'shaman' also derives from Proto-Tungusic" and may have roots that extend back in time at least two millennia.[3] The term was introduced to the west after Russian forces conquered the shamanistic Khanate of Kazan in 1552.

The term "shamanism" was first applied by Western anthropologists as outside observers of the ancient religion of the Turks and Mongols, as well as those of the neighbouring Tungusic and Samoyedic-speaking peoples. Upon observing more religious traditions across the world, some Western anthropologists began to also use the term in a very broad sense. The term was used to describe unrelated magico-religious practices found within the ethnic religions of other parts of Asia, Africa, Australasia and even completely unrelated parts of the Americas, as they believed these practices to be similar to one another.[4]

Mircea Eliade writes, "A first definition of this complex phenomenon, and perhaps the least hazardous, will be: shamanism = 'technique of religious ecstasy'."[5] Shamanism encompasses the premise that shamans are intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds. Shamans are said to treat ailments/illness by mending the soul. Alleviating traumas affecting the soul/spirit restores the physical body of the individual to balance and wholeness. The shaman also enters supernatural realms or dimensions to obtain solutions to problems afflicting the community. Shamans may visit other worlds/dimensions to bring guidance to misguided souls and to ameliorate illnesses of the human soul caused by foreign elements. The shaman operates primarily within the spiritual world, which in turn affects the human world. The restoration of balance results in the elimination of the ailment.[5]

Beliefs and practices that have been categorised this way as "shamanic" have attracted the interest of scholars from a wide variety of disciplines, including anthropologists, archaeologists, historians, religious studies scholars, philosophers and psychologists. Hundreds of books and academic papers on the subject have been produced, with a peer-reviewed academic journal being devoted to the study of shamanism. In the 20th century, many Westerners involved in the counter-cultural movement have created modern magico-religious practices influenced by their ideas of indigenous religions from across the world, creating what has been termed neoshamanism or the neoshamanic movement.[6] It has affected the development of many neopagan practices, as well as faced a backlash and accusations of cultural appropriation,[7] exploitation and misrepresentation when outside observers have tried to represent cultures they do not belong to.[8][9]

Le chamanisme est une pratique centrée sur la médiation entre les êtres humains et les esprits de la nature ou les âmes du gibier, les morts du clan, les âmes des enfants à naître, les âmes des malades à guérir, la communication avec des divinités, etc. C'est le chamane qui incarne cette fonction, dans le cadre d'une interdépendance étroite avec la communauté qui le reconnaît comme tel.

Le chamanisme, au sens strict (chamane vient étymologiquement de la langue toungouse), prend sa source dans les sociétés traditionnelles sibériennes. Partie de la Sibérie, la pensée chamanique a essaimé de la Baltique à l'Extrême-Orient et a sans doute franchi le détroit de Béring avec les premiers Amérindiens. On observe des pratiques analogues chez de nombreux peuples, à commencer par les Mongols, les Turcs et les Magyars1 (avant leur christianisation), qui seraient tous originaires de Sibérie, mais aussi au Népal, en Chine, en Corée, au Japon, chez les Scandinaves, chez les Amérindiens d'Amérique du Nord, en Afrique, en Australie, chez les Amérindiens d'Amérique latine2 et également chez les Celtes (druidisme orthodoxe).

Sciamanesimo (o sciamanismo) indica, nella storia delle religioni, in antropologia culturale e in etnologia, un insieme di credenze, pratiche religiose, tecniche magico-rituali, estatiche ed etnomediche riscontrabili in varie culture e tradizioni[1].

El chamanismo se refiere a una clase de creencias y prácticas tradicionales similares al animismo que aseguran la capacidad de diagnosticar y de curar el sufrimiento del ser humano, y en algunas sociedades, la capacidad de causarlo. Los chamanes creen lograrlo contactando con el mundo de los espíritus y formando una relación especial con ellos. Aseguran tener la capacidad de controlar el tiempo, profetizar, interpretar los sueños, usar la proyección astral y viajar a los mundos superior e inferior. Las tradiciones de chamanismo han existido en todo el mundo desde épocas prehistóricas.

Algunos especialistas en antropología definen al chamán como un intermediario entre el mundo natural y espiritual, que viaja entre los mundos en un estado de trance. Una vez en el mundo de los espíritus, se comunica con ellos para conseguir ayuda en la curación, la caza o el control del tiempo. Michael Ripinsky-Naxon describe a los chamanes como «personas que tienen fuerte ascendencia en su ambiente circundante y en la sociedad de la que forman parte».

Un segundo grupo de antropólogos discuten el término chamanismo, señalando que es una palabra para una institución cultural específica que, al incluir a cualquier sanador de cualquier sociedad tradicional, produce una uniformidad falsa entre estas culturas y crea la idea equívoca de la existencia de una religión anterior a todas los demás. Otros les acusan de ser incapaces de reconocer las concordancias entre las diversas sociedades tradicionales.

El chamanismo se basa en la premisa de que el mundo visible está impregnado por fuerzas y espíritus invisibles de dimensiones paralelas que coexisten simultáneamente con la nuestra, que afectan todas a las manifestaciones de la vida. En contraste con el animismo, en el que todos y cada uno de los miembros de la sociedad implicada lo practica, el chamanismo requiere conocimientos o capacidades especializados. Se podría decir que los chamanes son los expertos empleados por los animistas o las comunidades animistas. Sin embargo, los chamanes no se organizan en asociaciones rituales o espirituales, como hacen los sacerdotes.

Geography

Geography

Transport and traffic

Transport and traffic

Military, defense and equipment

Military, defense and equipment

Automobile

Automobile

Religion

Religion