Deutsch-Chinesische Enzyklopädie, 德汉百科

History

History

Amberg (Ausspracheⓘ/?) ist eine kreisfreie Stadt im Regierungsbezirk Oberpfalz in Ostbayern und gehört zur Metropolregion Nürnberg. Sie liegt an der Bayerischen Eisenstraße, die zwischen Pegnitz und Regensburg historische Industrie- und Kulturdenkmäler verbindet.

安贝格(德语:Amberg,德语:[ˈambɛrk] (ⓘ))是德国巴伐利亚州东部的一座非县辖城市, 位于纽伦堡以东约60千米的菲尔斯河畔,是欧洲现存最完好的中世纪城市之一。

安比奥里克斯( 高卢语: Ambiorix,意为“在各个方位皆为王”)是罗马共和国末期高卢东北部(比利时高卢地区)贝尔盖人的一位王子,也是当地厄勃隆内斯部落的领袖。在十九世纪,由于在恺撒高卢征伐过程中对后者的顽强抵抗(见恺撒的高卢战记),安比奥里克斯逐渐成为比利时的民族英雄 。

Ambiorix war ein Doppelkönig des keltischen Stammes der Eburonen. Zusammen mit Catuvolcus regierte er in der Zeit um 54/53 v. Chr.[1] Unter seiner Führung lehnten sich die Eburonen im November 54 v. Chr. gegen die römische Besatzungsmacht auf. Bei Atuatuca wurden dabei eineinhalb Legionen vernichtet. Im Herbst 53 v. Chr. und erneut im Jahr 51 v. Chr. plünderten, verwüsteten und entvölkerten römische Kriegstruppen unter Gaius Iulius Caesar das Siedlungsgebiet der Eburonen zwischen Rhein und Maas.

阿梅莉亚·玛丽·埃尔哈特(英语:Amelia Mary Earhart,1897年7月24日-1937年7月2日失踪,1939年1月5日被宣布死亡)是一位美国女性飞行员和女权运动者[1][2]。埃尔哈特是第一位获得飞行优异十字勋章[3]、第一位独自飞越大西洋的女飞行员[4]。她还创了许多其他纪录[5],将自身的飞行经历编写成非常畅销的书籍,并协助建立了一个女飞行员组织[6]。

1937年,当她尝试全球首次环球飞行时,在飞越太平洋期间失踪。至今为止,她的生活、生涯和消失一直使人神往[7]。

Amelia Mary Earhart (* 24. Juli 1897 in Atchison, Kansas; verschollen am 2. Juli 1937 im Pazifischen Ozean, für tot erklärt am 5. Januar 1939) war eine US-amerikanische Flugpionierin und Frauenrechtlerin.

美国革命是指在后半18世纪导致了北美洲十三个州的殖民地脱离大英帝国并且创建了美利坚合众国的一连串事件与思想。美国独立战争(1775年-1783 年)是革命的其中一部分,然而革命在莱辛顿(Lexington)与康考德(Concord)打响的第一发子弹之前就已经开始了,并且在英国于约克镇投降之后还持续下去。

1. California did not have the first gold rush in American history.

That honor actually belongs to North Carolina. Fifty years before gold was discovered at Sutter’s mill, the first gold rush in American history got underway after a 17-pound gold nugget was found in Cabarrus County, North Carolina. Eventually, more than 30,000 people in the Tar Heel state were mining for gold, and for more than 30 years all gold coins issued by the U.S. Mint were produced using North Carolina gold.

2. The Gold Rush was the largest mass migration in U.S. history.

In March 1848, there were roughly 157,000 people in the California territory; 150,000 Native Americans, 6,500 of Spanish or Mexican descent known as Californios and fewer than 800 non-native Americans. Just 20 months later, following the massive influx of settlers, the non-native population had soared to more than 100,000. And the people just kept coming. By the mid 1850s there were more than 300,000 new arrivals—and one in every 90 people in the United States was living in California. All of these people (and all of this money) helped fast track California to statehood. In 1850, just two years after the U.S. government had purchased the land, California became the 31st state in the Union.

3. The Gold Rush attracted immigrants from around the world.

In fact, by 1850 more than 25 percent of California’s population had been born outside the United States. As news of the discovery was slow to reach the east coast, many of the first immigrants to arrive were from South America and Asia. By 1852, more than 25,000 immigrants from China alone had arrived in America. As the amount of available gold began to dwindle, miners increasingly fought one another for profits and anti-immigrant tensions soared. The government got into the action too. In 1850 California’s legislature passed a Foreign Miner’s tax, which levied a monthly fee of $20 on non-citizens, the equivalent of more than $500 in today’s money. That bill was eventually repealed, but was replaced with another in 1852 that expressly singled out Chinese miners, charging them $2 ($80 today) a month.

4. The Gold Rush proved dangerous and deadly for non-white people.

During the Gold Rush, violence against foreign miners increased, with beatings, rapes and even murders becoming commonplace. However no ethnic group suffered more than California’s Native Americans. Before the Gold Rush, the state's native population numbered roughly 300,000. Within 20 years, more than 100,000 would be dead. Most died from disease or mining-related accidents, but more than 4,000 were murdered by enraged miners.

5. The Gold Rush was a male-dominated event.

Hundreds of thousands of people flocked to California to make their fortunes in the Gold Rush, but almost none of them were women. In 1852, 92 percent of the people prospecting for gold were men. The few women who did travel to the west eked out a living in the growing boomtowns, working in the restaurants, saloons and hotels that seemingly popped up every day. Some women’s journals back east, fearful of the trouble the men might get into without the civilizing influence of women, published stories and ran ads encouraging educated, morally minded young women to travel west to tame these men. Few took them up on this offer. The percentage of women in gold mining communities did eventually increase somewhat, but even in 1860 they numbered fewer than 10,000—just 19 percent.

6. Early sections of San Francisco were built out of ships abandoned by prospectors.

The Gold Rush conjures up images of thousands of “’49ers” heading west in wagons to strike it rich in California, but many of the first prospectors actually arrived by ship—and few of them had a return ticket. Within months, San Francisco’s port was teeming with boats that had been abandoned after their passengers—and crew—headed inland to hunt for gold. As the formerly tiny town began to boom, demand for lumber increased dramatically, and the ships were dismantled and sold as construction material. Hundreds of houses, banks, saloons, hotels, jails and other structures were built out of the abandoned ships, while others were used as landfill for lots near the waters edge. Today, more than 150 years after the Gold Rush began, archeologists and preservations continue to find relics, sometimes even entire ships, beneath the streets of the City by the Bay.

7. Prospecting for gold was a very costly enterprise.

Most of the men who flocked to northern California arrived with little more than the clothes on their backs. Once there, they needed to buy food, goods and supplies, which San Francisco’s merchants were all too willing to provide—for a cost. Stuck in a remote region, far from home, many prospectors coughed up most of their hard-earned money for the most basic supplies. At the height of the boom in 1849, prospectors could expect prices sure to cause sticker shock: A single egg could cost the equivalent of $25 in today’s money, coffee went for more than $100 per pound and replacing a pair of worn out boots could set you back more than $2,500.

8. More fortunes were made by merchants than by miners.

As the boom continued, more and more men got out of the gold-hunting business and began to open businesses catering to newly arrived prospectors. In fact, some of America’s greatest industrialists got their start in the Gold Rush. Phillp Armour, who would later found a meatpacking empire in Chicago, made a fortune operating the sluices that controlled the flow of water into the rivers being mined. Before John Studebaker built one of America’s great automobile fortunes, he manufactured wheelbarrows for Gold Rush miners. And two entrepreneurial bankers named Henry Wells and William Fargo moved west to open an office in San Francisco, an enterprise that soon grew to become one of America’s premier banking institutions. One of the biggest mercantile success stories was that of Levi Strauss. A German-born tailor, Strauss arrived in San Francisco in 1850 with plans to open a store selling canvas tarps and wagon coverings to the miners. After hearing that sturdy work pants—ones that could withstand the punishing 16-hour days regularly put in by miners—were more in demand, he shifted gears, opening a store in downtown San Francisco that would eventually become a manufacturing empire, producing Levi’s denim jeans.

9. Thousands of Gold Rush prospectors got rich—but John Sutter wasn’t one of them.

John Sutter, the man whose land would become synonymous with the California Gold Rush, was a Swiss immigrant who fled Europe in the 1830s, leaving behind piles of unpaid debts. After several years of traveling throughout North America, he finally settled in the tiny outpost of Yuerba Buena (modern-day San Francisco) in 1839. With the assistance of the local Mexican government, Sutter quickly realized his goal of establishing an agricultural community on a 50,000-acre tract of land he called “New Helvetia,” Latin for “New Switzerland, which became an important outpost for emigrants traveling to the west.

It was during the construction of a sawmill on Sutter’s land along the American River that one of his employees first discovered the gold nugget that would change the world. Sutter, initially more interested in maintaining control over his property, tried to keep the discovery quiet, but the news quickly leaked out. Within months, most of his workers had abandoned him to search for gold themselves, while thousands of other prospectors overran and destroyed much of his land and equipment. Faced with mounting debts, Sutter was forced to deed his land to one of his sons, who used it to create a new settlement called Sacramento. Sutter Sr. was furious—he had hoped the town would be named after him—but he had more pressing concerns. Nearly bankrupt, he began a decades-long campaign to have the U.S. government reimburse him for his financial losses, to no avail. While thousands became rich off his former land, a bitter Sutter retired to Pennsylvania and died.

自由主一語民主制度的原則—美國的政治基礎—天生源自於在處女地上建立新社會的過程。自然地,新國家將自視為獨特與優秀。歐洲將懷有恐懼或希望地觀察它。

1700年代,英國的北美13州殖民地日趨成熟,在人口、經濟能力與文化成就皆有所成長。他們經歷自治,然而直到150年後第一個永久的屯懇地於維吉尼亞的詹姆士城建立,新美利堅合眾國才成為國家。

1750年代,英法之間的戰爭有部分在北美進行。英國獲勝,並很快開始實施用以控制其強大帝國並累積其財富。這些措施對美國殖民地居民的生活方式造成更大的限制。

1763年的皇家宣言(Royal Proclamation)限制屯懇區新土地的開發。1764年蔗糖法案(Sugar Act)對奢華物品課稅,包括咖啡、絲、牛奶與酒,並且規定進口酒為非法行為。1764年貨幣法案(Currency Act)禁止在殖民地印刷紙鈔。1765年駐營法案(Quartering Act)強迫殖民地居民為皇家軍隊提供食物與住宿。1765年印花稅法(Stamp Act)規定為所有法律文件、報紙、執照與合約而購買印花稅票。(Quelle: usinfo.org/PUBS/HistoryBrief/road.htm)

不空金刚(梵语:अमोघवज्र,罗马化:Amoghavajra,705年—774年),音译阿目佉跋折罗,佛教译经师,唐密祖师之一,力于金刚顶瑜伽部及杂密中金刚大道场经的一字佛顶法,和文殊咒藏的阎曼德迦法、金翅鸟法、摩利支法等,撰有《总释陀罗尼义赞》等著作。

不空是南天竺师子国人[1],自幼聪颖,十四岁时(718年,开元六年),在阇婆国[2]依止金刚智。720年(开元八年)左右,随金刚智到洛阳。724年(开元十二年),于广福寺依说一切有部律仪受具足戒。由于才华出众,通晓多种语言,金刚智出经时,常请不空作译语。

不空欲得瑜伽五部三密法,但金刚智三年未允,于是准备远赴天竺求法,金刚智观察梦兆,知是真法器,于是将五部灌顶、护摩阿阇黎教法、大日经悉地仪轨、诸佛顶部诸多真言仪轨等,悉数教授不空。

Amoghavajra (Sanskrit: अमोघवज्र Amoghavajra; Chinesisch: 不空; Pinyin: Bùkōng; Japanisch: Fukū; koreanisch: 불공; vietnamesisch: Bất Không, 705-774) war ein produktiver Übersetzer, der zu einem der politisch mächtigsten buddhistischen Mönche in der chinesischen Geschichte wurde und als einer der Acht Patriarchen der Lehre im Shingon-Buddhismus anerkannt ist.

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt

International cities

International cities

Bavaria

Bavaria

Vacation and Travel

Vacation and Travel

Art

Art

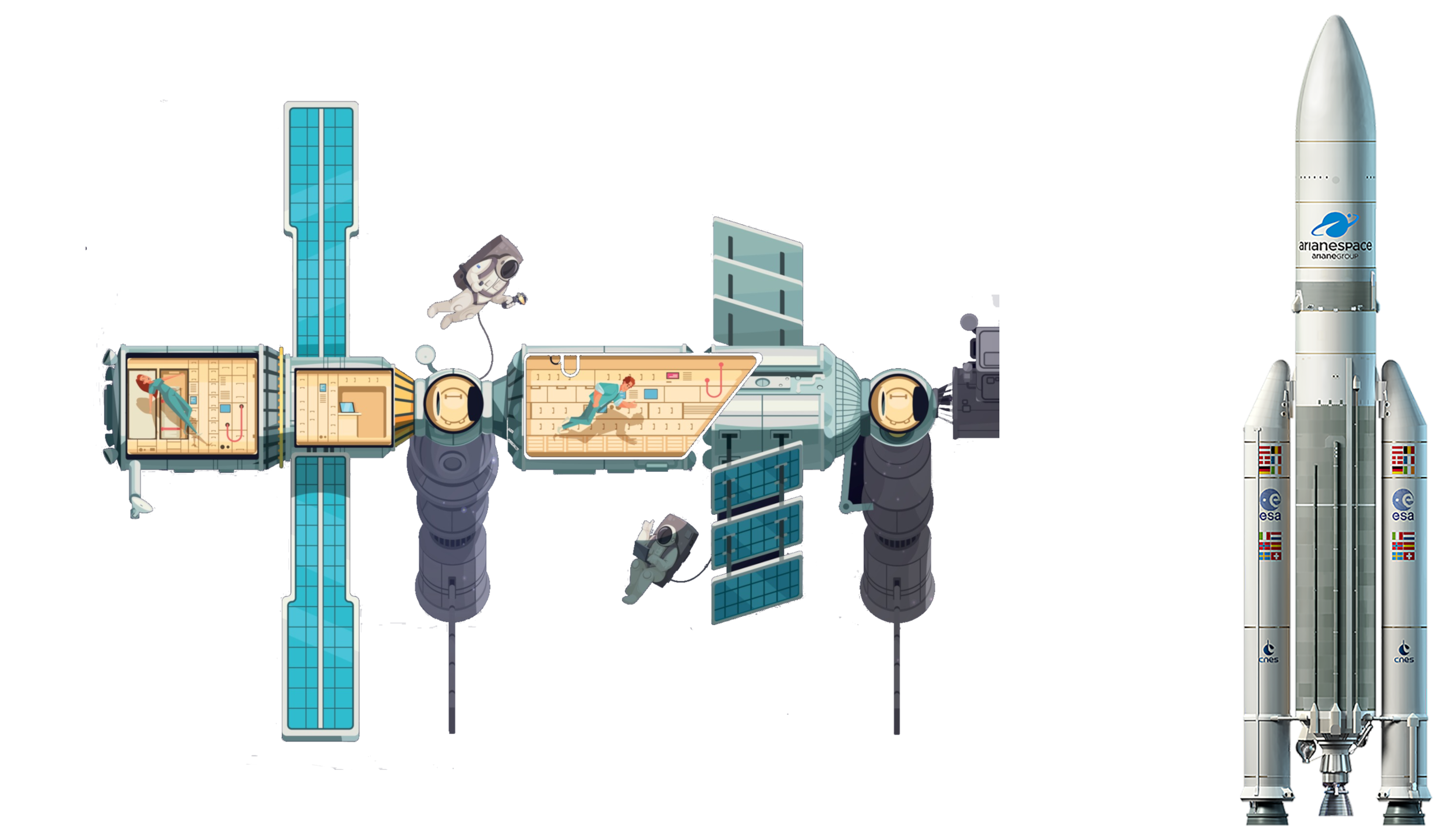

Aerospace

Aerospace

Military, defense and equipment

Military, defense and equipment

Review

Review

Abruzzo

Abruzzo

Architecture

Architecture

Religion

Religion