漢德百科全書 | 汉德百科全书

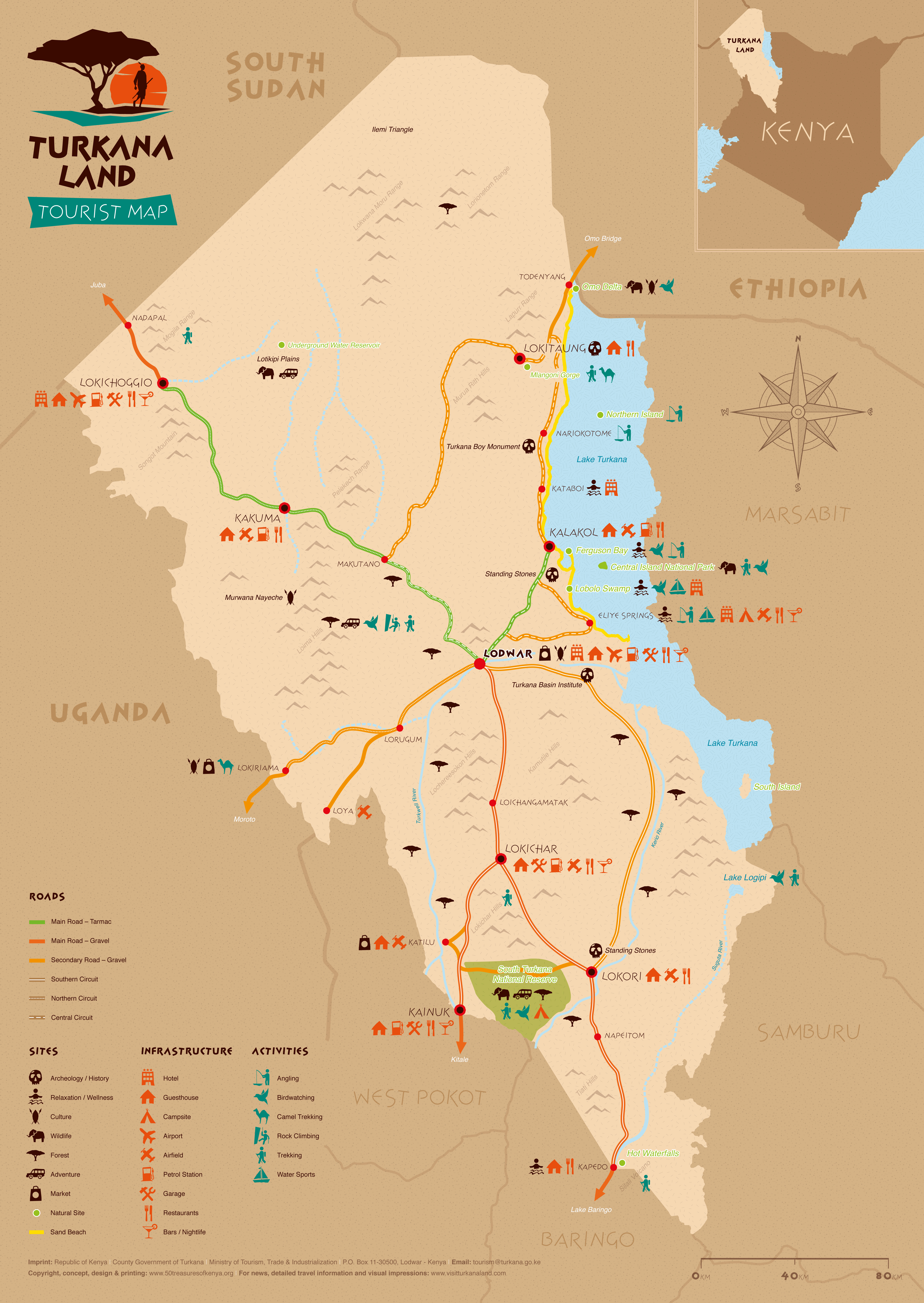

Kenya

Kenya

Afghanistan

Afghanistan

Egypt

Egypt

Argentina

Argentina

Armenia

Armenia

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan

Bangladesh

Bangladesh

Beijing Shi-BJ

Beijing Shi-BJ

Belarus

Belarus

Belgium

Belgium

Amber Road

Amber Road

Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Chile

Chile

China

China

Chongqing Shi-CQ

Chongqing Shi-CQ

Germany

Germany

Eritrea

Eritrea

Fidschi

Fidschi

Financial

Financial

Financial

Financial

*China economic data

*China economic data

France

France

Fujian Sheng-FJ

Fujian Sheng-FJ

Gansu Sheng-GS

Gansu Sheng-GS

Georgia

Georgia

Greece

Greece

Guangdong Sheng-GD

Guangdong Sheng-GD

Guangxi Zhuangzu Zizhiqu-GX

Guangxi Zhuangzu Zizhiqu-GX

Hainan Sheng-HI

Hainan Sheng-HI

Hand in Hand

Hand in Hand

Hebei Sheng-HE

Hebei Sheng-HE

Heilongjiang Sheng-HL

Heilongjiang Sheng-HL

Henan Sheng-HA

Henan Sheng-HA

Hongkong Tebiexingzhengqu-HK

Hongkong Tebiexingzhengqu-HK

India

India

Indonesia

Indonesia

Iraq

Iraq

Iran

Iran

Italy

Italy

Japan

Japan

Yemen

Yemen

Jiangsu Sheng-JS

Jiangsu Sheng-JS

Jilin Sheng-JL

Jilin Sheng-JL

Jordan

Jordan

Cambodia

Cambodia

Kasachstan

Kasachstan

Kenya

Kenya

Kenya

Kenya

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan

Laos

Laos

Liaoning Sheng-LN

Liaoning Sheng-LN

Madagaskar

Madagaskar

Malaysia

Malaysia

Mongolei

Mongolei

Myanmar

Myanmar

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Nepal

Nepal

Netherlands

Netherlands

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Oman

Oman

Austria

Austria

Pakistan

Pakistan

Philippines

Philippines

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Qinghai Sheng-QH

Qinghai Sheng-QH

Republic of Korea

Republic of Korea

Republic of the Sudan

Republic of the Sudan

Russia

Russia

Switzerland

Switzerland

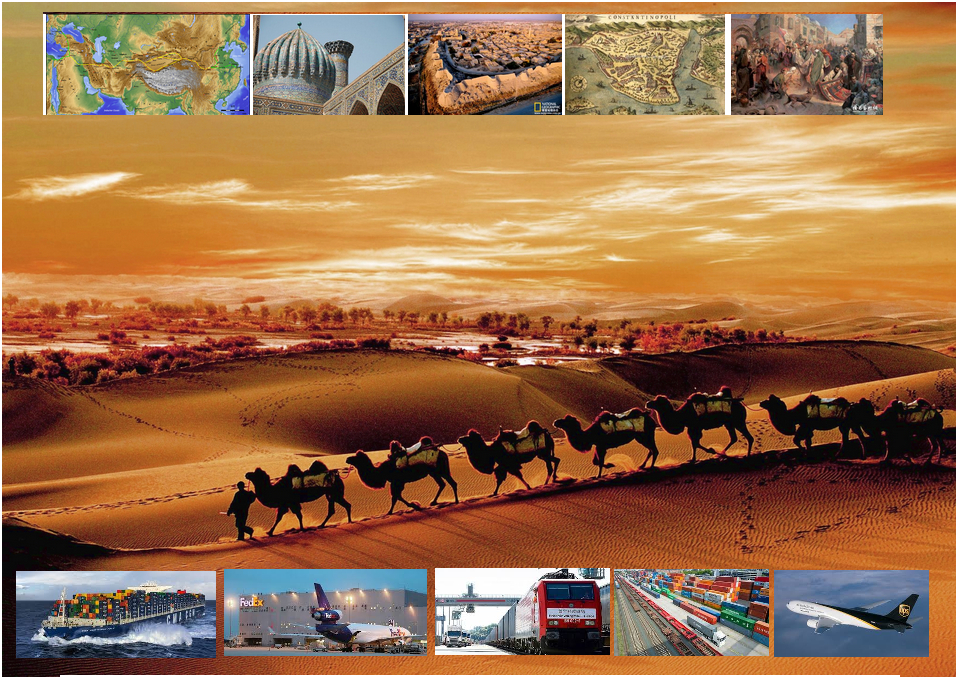

Silk road

Silk road

Serbia

Serbia

Serbia

Serbia

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shanghai Shi-SH

Shanghai Shi-SH

Sichuan Sheng-SC

Sichuan Sheng-SC

Singapore

Singapore

Slovakia

Slovakia

Somalia

Somalia

Spain

Spain

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

South Africa

South Africa

Syria

Syria

Tajikistan

Tajikistan

Taiwan Sheng-TW

Taiwan Sheng-TW

Tianjin Shi-TJ

Tianjin Shi-TJ

Tianjin Shi-TJ

Tianjin Shi-TJ

Czech Republic

Czech Republic

Czech Republic

Czech Republic

Turkey

Turkey

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan

Ukraine

Ukraine

Hungary

Hungary

Vacation and Travel

Vacation and Travel

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Vietnam

Vietnam

World Heritage

World Heritage

Economy and trade

Economy and trade

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

Als Seidenstraße (chinesisch 絲綢之路 / 丝绸之路, Pinyin Sīchóu zhī Lù ‚die Route / Straße der Seide‘; mongolisch ᠲᠣᠷᠭᠠᠨ ᠵᠠᠮ Tôrgan Jam; kurz: 絲路 / 丝路, Sīlù) bezeichnet man ein altes Netz von Karawanenstraßen, dessen Hauptroute den Mittelmeerraum auf dem Landweg über Zentralasien mit Ostasien verband. Die Bezeichnung geht auf den im 19. Jahrhundert lebenden deutschen Geografen Ferdinand von Richthofen zurück, der den Begriff 1877 erstmals verwendet hat.

Auf der antiken Seidenstraße wurde in westliche Richtung hauptsächlich Seide, gen Osten vor allem Wolle, Gold und Silber gehandelt.[1] Nicht nur Kaufleute, Gelehrte und Armeen nutzten ihr Netz, sondern auch Ideen, Religionen und ganze Kulturkreise diffundierten und migrierten auf den Routen von Ost nach West und umgekehrt: hierüber kamen z. B. der Nestorianismus (aus dem spätantiken Römischen Reich) und der Buddhismus (von Indien) nach China.[1]

Die 6.400 Kilometer[1] lange Route begann in Xi’an und folgte dem Verlauf der Chinesischen Mauer in Richtung Nordwesten, passierte die Taklamakan-Wüste, überwand das Pamirgebirge und führte über Afghanistan in die Levante; von hier wurden die Handelsgüter dann über das Mittelmeer verschifft. Nur wenige Kaufleute reisten auf der gesamten Route, die Waren wurden eher gestaffelt über Zwischenhändler transportiert.

Ihre größte Bedeutung erreichte das Handels- und Wegenetz zwischen 115 v. Chr. und dem 13. Jahrhundert n. Chr. Mit dem allmählichen Verlust römischen Territoriums in Asien und dem Aufstieg Arabiens in der Levante wurde die Seidenstraße zunehmend unsicher und kaum noch bereist. Im 13. und 14. Jahrhundert wurde die Strecke unter den Mongolen wiederbelebt, u. a. benutzte sie zu der Zeit der Venezianer Marco Polo um nach Cathay (China) zu reisen. Nach weit verbreiteter Ansicht war die Route einer der Hauptwege, über die Mitte des 14. Jahrhunderts Pestbakterien von Asien nach Europa gelangten und dort den Schwarzen Tod verursachten.[1]

Teile der Seidenstraße sind zwischen Pakistan und dem autonomen Gebiet Xinjiang in China heute noch als asphaltierte Fernstraße vorhanden (-> Karakorum Highway). Die alte Straße inspirierte die Vereinten Nationen zu einem Plan für eine transasiatische Fernstraße. Von der UN-Wirtschafts- und Sozialkommission für Asien und den Pazifik (UNESCAP) wird die Einrichtung einer durchgehenden Eisenbahnverbindung entlang der Route vorangetrieben, der Trans-Asian Railway.[1]

Die "Neue Seidenstraße", das "One Belt, One Road"-Projekt der Volksrepublik China unter ihrem Staatspräsident Xi Jinping umfasst landgestützte (Silk Road Economic Belt) und maritime (Maritime Silk Road) Infrastruktur- und Handelsrouten, Wirtschaftskorridore und Transportlinien von China über Zentralasien und Russland bzw. über Afrika nach Europa, dazu werden verschiedenste Einrichtungen (z. B. Tiefsee- oder Containerterminals) und Verbindungen (wie Bahnlinien oder Gaspipelines) entwickelt bzw. ausgebaut. Bestehende Korridore sind einerseits Landverbindungen über die Türkei oder Russland und andererseits Anknüpfungen zum Hafen von Shanghai, über Hongkong und Singapur nach Indien und Ostafrika, Dubai, den Suez-Kanal, den griechischen Hafen Piräus nach Venedig.[2]

Das Projekt One Belt, One Road (OBOR, chinesisch 一帶一路 / 一带一路, Pinyin Yídài Yílù ‚Ein Band, Eine Straße‘, neuerdings Belt and Road, da „One“ zu negativ besetzt war) bündelt seit 2013 die Interessen und Ziele der Volksrepublik China unter Staatspräsident Xi Jinping zum Auf- und Ausbau interkontinentaler Handels- und Infrastruktur-Netze zwischen der Volksrepublik und zusammen 64 weiteren Ländern Afrikas, Asiens und Europas. Die Initiative bzw. das Gesamtprojekt betrifft u. A. rund 62 % der Weltbevölkerung und ca. 35 % der Weltwirtschaft.[1][2]

Umgangssprachlich wird das Vorhaben auch „Belt and Road Initiative“ (B&R, BRI) bzw. ebenso wie das Projekt Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia (TRACECA) auch „Neue Seidenstraße“ (新絲綢之路 / 新丝绸之路, Xīn Sīchóuzhīlù) genannt. Es bezieht sich auf den geografischen Raum des historischen, bereits in der Antike genutzten internationalen Handelskorridors „Seidenstraße“; zusammengefasst handelt es sich um zwei Bereiche, einen nördlich gelegenen zu Land mit sechs Bereichen unter dem Titel Silk Road Economic Belt und einen südlich gelegenen Seeweg namens Maritime Silk Road.

丝绸之路(德语:Seidenstraße;英语:Silk Road),常简称为丝路,此词最早来自于德意志帝国地理学家费迪南·冯·李希霍芬男爵于1877年出版的一套五卷本的地图集。[1]

丝绸之路通常是指欧亚北部的商路,与南方的茶马古道形成对比,西汉时张骞以长安为起点,经关中平原、河西走廊、塔里木盆地,到锡尔河与乌浒河之间的中亚河中地区、大伊朗,并联结地中海各国的陆上通道。这条道路也被称为“陆路丝绸之路”,以区别日后另外两条冠以“丝绸之路”名称的交通路线。因为由这条路西运的货物中以丝绸制品的影响最大,故得此名。其基本走向定于两汉时期,包括南道、中道、北道三条路线。但实际上,丝绸之路并非是一条 “路”,而是一个穿越山川沙漠且没有标识的道路网络,并且丝绸也只是货物中的一种。[1]:5

广义的丝绸之路指从上古开始陆续形成的,遍及欧亚大陆甚至包括北非和东非在内的长途商业贸易和文化交流线路的总称。除了上述的路线之外,还包括约于前5世纪形成的草原丝绸之路、中古初年形成,在宋代发挥巨大作用的海上丝绸之路和与西北丝绸之路同时出现,在宋初取代西北丝绸之路成为路上交流通道的南方丝绸之路。

虽然丝绸之路是沿线各君主制国家共同促进经贸发展的产物,但很多人认为,西汉的张骞在前138—前126年和前119年曾两次出使西域,开辟了中外交流的新纪元,并成功将东西方之间最后的珠帘掀开。司马迁在史记中说:“于是西北国始通于汉矣。然张骞凿空,其后使往者皆称博望侯,以为质与国外,外国由此信之”,称赞其开通西域的作用。从此,这条路线被作为“国道”踩了出来,各国使者、商人、传教士等沿着张骞开通的道路,来往络绎不绝。上至王公贵族,下至乞丐狱犯,都在这条路上留下了自己的足迹。这条东西通路,将中原、西域与大伊朗、累范特、阿拉伯紧密联系在一起。经过几个世纪的不断努力,丝绸之路向西伸展到了地中海。广义上丝路的东段已经到达了朝鲜、日本,西段至法国、荷兰。通过海路还可达意大利、埃及,成为亚洲和欧洲、非洲各国经济文化交流的友谊之路。

丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路(英语:The Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road[1]),简称一带一路(英语:The Belt and Road Initiative,缩写B&R)[1],是中华人民共和国政府于2013年倡议[2]并主导的跨国经济带[3]。

一带一路范围涵盖历史上丝绸之路和海上丝绸之路行经的中国、中亚、北亚和西亚、印度洋沿岸、地中海沿岸的国家和地区。中国政府指出,“一带一路”倡议坚持共商、共建、共享的原则,努力实现沿线区域基础设施更加完善,更加安全高效,以形成更高水平的陆海空交流网络。同时使投资贸易的便利化水平更有效的提升,建立高品质、高标准的自由贸易区域网。以使沿线各国经济联系更加紧密,政治互信更加的深入,人文交流更加的广泛[4]。

シルクロード(絹の道、英語: Silk Road, ドイツ語: Seidenstraße, 繁体字:絲綢之路, 簡体字:丝绸之路)は、中国と地中海世界の間の歴史的な交易路を指す呼称である。絹が中国側の最も重要な交易品であったことから名付けられた。その一部は2014年に初めて「シルクロード:長安-天山回廊の交易路網」としてユネスコの世界遺産に登録された。

「シルクロード」という名称は、19世紀にドイツの地理学者リヒトホーフェンが、その著書『China(支那)』(1巻、1877年)においてザイデンシュトラーセン(ドイツ語:Seidenstraßen;「絹の道」の複数形)として使用したのが最初であるが、リヒトホーフェンは古来中国で「西域」と呼ばれていた東トルキスタン(現在の中国新疆ウイグル自治区)を東西に横断する交易路、いわゆる「オアシスの道(オアシスロード)」を経由するルートを指してシルクロードと呼んだのである。リヒトホーフェンの弟子で、1900年に楼蘭の遺跡を発見したスウェーデンの地理学者ヘディンが、自らの中央アジア旅行記の書名の一つとして用い、これが1938年に『The Silk Road』の題名で英訳されて広く知られるようになった。

シルクロードの中国側起点は長安(陝西省西安市)、欧州側起点はシリアのアンティオキアとする説があるが、中国側は洛陽、欧州側はローマと見る説などもある。日本がシルクロードの東端だったとするような考え方もあり、特定の国家や組織が経営していたわけではないのであるから、そもそもどこが起点などと明確に定められる性質のものではない。

現在の日本でこの言葉が使われるときは、特にローマ帝国と秦・漢帝国、あるいは大唐帝国の時代の東西交易が念頭に置かれることが多いが、広くは近代(大航海時代)以前のユーラシア世界の全域にわたって行われた国際交易を指し、南北の交易路や海上の交易路をも含める。つまり、北方の「草原の道(ステップロード)」から南方の「海の道(シーロード)」までを含めて「シルクロード」と呼ばれるようになっているわけである。

シルクロード経済ベルトと21世紀海洋シルクロード(シルクロードけいざいベルトと21せいきかいようシルクロード、拼音: 、英語: The Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road)とは、2014年11月10日に中華人民共和国北京市で開催されたアジア太平洋経済協力首脳会議で、習近平総書記が提唱した経済圏構想である。

略称は一帯一路(いったいいちろ、拼音: 、英語: The Belt and Road Initiative, BRI; One Belt, One Road Initiative, OBOR)。

The Silk Road was an ancient network of trade routes that connected the East and West. It was central to cultural interaction between the regions for many centuries.[1][2][3] The Silk Road refers to both the terrestrial and the maritime routes connecting East Asia and Southeast Asia with East Africa, West Asia and Southern Europe.

The Silk Road derives its name from the lucrative trade in silk carried out along its length, beginning in the Han dynasty (207 BCE–220 CE). The Han dynasty expanded the Central Asian section of the trade routes around 114 BCE through the missions and explorations of the Chinese imperial envoy Zhang Qian.[4] The Chinese took great interest in the safety of their trade products and extended the Great Wall of China to ensure the protection of the trade route.[5]

Trade on the Road played a significant role in the development of the civilizations of China, Korea,[6] Japan,[2] India, Iran, Afghanistan, Europe, the Horn of Africa and Arabia, opening long-distance political and economic relations between the civilizations.[7] Though silk was the major trade item exported from China, many other goods were traded, as well as religions, syncretic philosophies, sciences, and technologies. Diseases, most notably plague, also spread along the Silk Road.[8] In addition to economic trade, the Silk Road was a route for cultural trade among the civilizations along its network.[9]

Traders in ancient history included the Bactrians, Sogdians, Syrians, Jews, Arabs, Iranians, Turkmens, Chinese, Malays, Indians, Somalis, Greeks, Romans, Georgians, Armenians, and Azerbaijanis.[10]

In June 2014, UNESCO designated the Chang'an-Tianshan corridor of the Silk Road as a World Heritage Site. The Indian portion is on the tentative site list.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) or the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road is a development strategy adopted by the Chinese government. The 'belt' refers to the overland interconnecting infrastructure corridors; the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) component. The 'road' refers to the sea route corridors; the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR) component.[2] The initiative focuses on connectivity and cooperation between Eurasian countries, primarily the People's Republic of China (PRC).

Until 2016 the initiative was known in English as the One Belt and One Road Initiative (OBOR) but the Chinese came to consider the emphasis on the word "one" as misleading.[3]

The Chinese government calls the initiative "a bid to enhance regional connectivity and embrace a brighter future".[4] Independent observers, however, see it as a push for Chinese dominance in global affairs with a China-centered trading network.[5][6]

La route de la soie est un réseau ancien de routes commerciales entre l'Asie et l'Europe, reliant la ville de Chang'an (actuelle Xi'an) en Chine à la ville d'Antioche, en Syrie médiévale (aujourd'hui en Turquie). Elle tire son nom de la plus précieuse marchandise qui y transitait : la soie.

La route de la soie était un faisceau de pistes par lesquelles transitaient de nombreuses marchandises, et qui monopolisa les échanges Est-Ouest pendant des siècles. Les plus anciennes traces connues de la route de la soie, comme voie de communication avec les populations de l'Ouest, remontent à « 2000 avant notre ère au moins ». Les Chinois en fixent l'ouverture au voyage de Zhang Qian en 138-1261. Mais la route de la soie s'est développée surtout sous la dynastie Han (221 av. J.-C. - 220 ap. J.-C.), en particulier Han Wudi.

Puis sous la dynastie Tang (618-907). À partir du XVe siècle, la route de la soie est progressivement abandonnée, l'instabilité des guerres turco-byzantines, puis la chute de Constantinople poussent en effet les Occidentaux à chercher une nouvelle route maritime vers les Indes. L'abandon de la route de la soie correspond ainsi au début de la période des « Grandes découvertes » durant laquelle les techniques de transport maritime deviennent de plus en plus performantes. Du côté chinois, les empereurs Ming Yongle, puis Ming Xuanzong chargent, à la même époque, l'amiral Zheng He d'expéditions maritimes similaires.

La nouvelle route de la soie ou la Ceinture et la Route2 (stratégie aussi appelée OBOR en anglais pour One Belt, One Road3) est à la fois un ensemble de liaisons maritimes et de voies ferroviaires entre la Chine et l'Europe passant par le Kazakhstan, la Russie, la Biélorussie, la Pologne, l'Allemagne, la France et le Royaume-Uni.

Le nouveau nom est Initiative route et ceinture (Belt and Road Initiative, B&R selon l’acronyme anglais) afin de marquer le fait que ce projet ne se limite pas à une seule route4.

Outre l'amélioration de la connectivité ferroviaire, il s'agit aussi d'une stratégie de développement pour promouvoir la coopération entre les pays sur une vaste bande s'étendant à travers l'Eurasie et pour renforcer la position de la Chine sur le plan mondial, par exemple en préservant la connexion de la Chine avec le reste du monde en cas de tensions militaires sur ses zones côtières5.

La Nouvelle route de la soie a été dévoilée à l'automne 2013 par le gouvernement chinois en tant que pendant terrestre du collier de perles6 ; elle est l'une des priorités de la diplomatie chinoise, sous la présidence de Xi Jinping7.

Selon CNN, ce projet englobera 68 pays représentant 4,4 milliards d’habitants et 62 % du PIB mondial8.

Per via della seta (in cinese: 絲綢之路T, 丝绸之路S, sī chóu zhī lùP; persiano: راه ابریشم, Râh-e Abrisham) s'intende il reticolo, che si sviluppava per circa 8.000 km, costituito da itinerari terrestri, marittimi e fluviali lungo i quali nell'antichità si erano snodati i commerci tra l'impero cinese e quello romano.

Le vie carovaniere attraversavano l'Asia centrale e il Medio Oriente, collegando Chang'an (oggi Xi'an), in Cina, all'Asia Minore e al Mediterraneo attraverso il Medio Oriente e il Vicino Oriente. Le diramazioni si estendevano poi a est alla Corea e al Giappone e, a Sud, all'India. Il nome apparve per la prima volta nel 1877, quando il geografo tedesco Ferdinand von Richthofen (1833-1905) pubblicò l'opera Tagebucher aus China. Nell'Introduzione von Richthofen nomina la Seidenstraße, la «via della seta».

La destinazione finale della seta che su di essa viaggiava (non certo da sola ma insieme a tante altre merci preziose) era Roma, dove per altro non si sapeva con precisione quale ne fosse l'origine (se animale o vegetale) e da dove provenisse. Altre merci altrettanto preziose viaggiavano in senso inverso, e insieme alle merci viaggiavano grandi idee e religioni (concetti fondamentali di matematica, geometria, astronomia) in entrambi i sensi, manicheismo, e nestorianesimo verso oriente. Sulla via della seta compì un complesso giro quasi in tondo anche il buddhismo, dall'India all'Asia Centrale alla Cina e infine al Tibet (il tutto per trovare itinerari che permettessero di evitare le quasi invalicabili montagne dell'Himalaya).

Questi scambi commerciali e culturali furono determinanti per lo sviluppo e il fiorire delle antiche civiltà dell'Egitto, della Cina, dell'India e di Roma, ma furono di grande importanza anche nel gettare le basi del mondo medievale e moderno.

La Nuova via della seta è un'iniziativa strategica della Cina per il miglioramento dei collegamenti e della cooperazione tra paesi nell'Eurasia. Comprende le direttrici terrestri della "zona economica della via della seta" e la "via della seta marittima del XXI secolo" (in cinese: 丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路S, Sīchóu zhī lù jīngjìdài hé èrshíyī shìjì hǎishàng sīchóu zhī lùP), ed è conosciuta anche come "iniziativa della zona e della via" (一带一路S, tradotta comunemente in inglese con Belt and Road Initiative, BRI) o "una cintura, una via" e col corrispondente iniziale acronimo inglese OBOR (One belt, one road), poi modificato in BRI per sottolineare l'estensione del progetto non esclusivo solo della Cina[1], nonostante la prospettiva sinocentrica, com'è stato illustrato in un recente studio italiano[2].

Partendo dallo sviluppo delle infrastrutture di trasporto e logistica, la strategia mira a promuovere il ruolo della Cina nelle relazioni globali, favorendo i flussi di investimenti internazionali e gli sbocchi commerciali per le produzioni cinesi. L'iniziativa di un piano organico per i collegamenti terrestri (la cintura) è stata annunciata pubblicamente dal presidente cinese Xi Jinping a settembre del 2013, e la via marittima ad ottobre dello stesso anno, contestualmente alla proposta di costituire la Banca asiatica d'investimento per le infrastrutture (AIIB), dotata di un capitale di 100 miliardi di dollari USA, di cui la Cina stessa sarebbe il principale socio, con un impegno pari a 29,8 miliardi e gli altri paesi asiatici (tra cui l'India e la Russia) e dell'Oceania avrebbero altri 45 miliardi (l'Italia si è impegnata a sottoscrivere una quota di 2,5 miliardi).

La Ruta de la Seda fue una red de rutas comerciales organizadas a partir del negocio de la seda china desde el siglo I a. C., que se extendía por todo el continente asiático, conectando a China con Mongolia, el subcontinente indio, Persia, Arabia, Siria, Turquía, Europa y África. Sus diversas rutas comenzaban en la ciudad de Chang'an (actualmente Xi'an) en China, pasando entre otras por Karakórum (Mongolia), el Paso de Khunjerab (China/Pakistán), Susa (Persia), el Valle de Fergana (Tayikistán), Samarcanda (Uzbekistán), Taxila (Pakistán), Antioquía en Siria, Alejandría (Egipto), Kazán (Rusia) y Constantinopla (actualmente Estambul, Turquía) a las puertas de Europa, llegando hasta los reinos hispánicos en el siglo XV, en los confines de Europa y a Somalia y Etiopía en el África oriental.

El término "Ruta de la Seda" fue creado por el geógrafo alemán Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen, quien lo introdujo en su obra Viejas y nuevas aproximaciones a la Ruta de la Seda, en 1877. Debe su nombre a la mercancía más prestigiosa que circulaba por ella, la seda, cuya elaboración era un secreto que solo los chinos conocían. Los romanos (especialmente las mujeres de la aristocracia) se convirtieron en grandes aficionados de este tejido, tras conocerlo antes del comienzo de nuestra era a través de los partos, quienes se dedicaban a su comercio. Muchos productos transitaban estas rutas: piedras y metales preciosos (diamantes de Golconda, rubíes de Birmania, jade de China, perlas del golfo Pérsico), telas de lana o de lino, ámbar, marfil, laca, especias, porcelana, vidrio, materiales manufacturados, coral, etc.

En junio de 2014, la Unesco eligió un tramo de la Ruta de la Seda como Patrimonio de la Humanidad con la denominación Rutas de la Seda: red viaria de la ruta del corredor Chang’an-Tian-shan. Se trata de un tramo de 5000 kilómetros de la gran red viaria de las Rutas de la Seda que va desde la zona central de China hasta la región de Zhetysu, situada en el Asia Central, incluyendo 33 nuevos sitios en China, Kazajistán y Kirguistán.1

La Iniciativa del Cinturón y Ruta de la Seda o Belt and Road Initiative, abreviada BRIZNA (también One Belt, One Road, abreviado OBOR y también la Nueva Ruta de la Seda) y NRS (Nueva Ruta de la Seda) por las siglas en español, es el nombre con que se conoce el proyecto político-económico del Secretario General del Partido Comunista de China, Xi Jinping, que propuso en septiembre de 2013 en sus respectivos viajes a Rusia, Kazajistán y Bielorrusia. Bajo el pretexto de que "hace más de dos milenios, las personas diligentes y valientes de Eurasia exploraron y abrieron nuevas vías de intercambio comercial y cultural que unían las principales civilizaciones de Asia, Europa y África, colectivamente llamadas ruta de la seda por generaciones posteriores", el proyecto quiere conectar Europa, Asia del Sur-Oriental, Asia Central y el Oriente Medio, mediante el modelo económico, e implícitamente político, chino.12

El proyecto parte de la reconstrucción de la antigua ruta de la seda y la creac

*UK political system

*UK political system

Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda

Australia

Australia

Bahamas

Bahamas

Bangladesh

Bangladesh

Barbados

Barbados

Belize

Belize

Botsuana

Botsuana

Brunei Darussalam

Brunei Darussalam

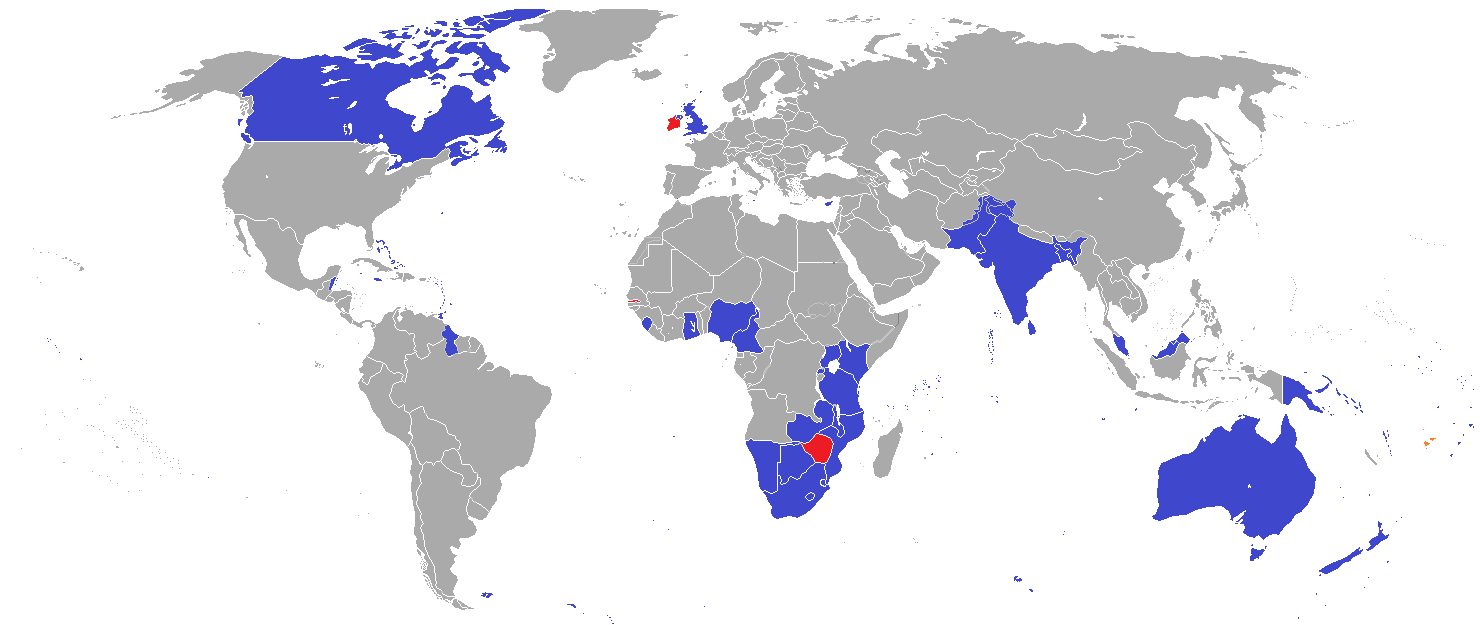

Commonwealth of Nations

Commonwealth of Nations

Dominica

Dominica

Ghana

Ghana

Grenada

Grenada

Guyana

Guyana

India

India

Jamaika

Jamaika

Cameroon

Cameroon

Canada

Canada

Kenya

Kenya

Kiribati

Kiribati

Lesotho

Lesotho

Malawi

Malawi

Malaysia

Malaysia

Malediven

Malediven

Malta

Malta

Mauritius

Mauritius

Mauritius

Mauritius

Mosambik

Mosambik

Namibia

Namibia

Nauru

Nauru

New Zealand

New Zealand

Nigeria

Nigeria

Pakistan

Pakistan

Papua-Neuguinea

Papua-Neuguinea

Salomonen

Salomonen

Sambia

Sambia

Samoa

Samoa

Seychellen

Seychellen

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone

Singapore

Singapore

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Kitts and Nevis

St. Vincent and the Grenadines

St. Vincent and the Grenadines

St. Vincent and the Grenadines

St. Vincent and the Grenadines

South Africa

South Africa

Swasiland

Swasiland

Tansania

Tansania

Tonga

Tonga

Trinidad und Tobago

Trinidad und Tobago

Tuvalu

Tuvalu

Uganda

Uganda

Vanuatu

Vanuatu

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Important International Organizations

Important International Organizations

Cyprus

Cyprus

英联邦(英语:Commonwealth of Nations,新马作共和联邦,台湾作大英国协),是一个现代的国际组织,由56个英语系的主权国家联合而成。

英联邦不是一个统一的联邦国家,而是一个国际组织,英联邦也无权约束旗下任何成员国内政。英联邦元首通常由英国君主兼任,其首任元首是乔治六世,现任是查尔斯三世,但元首并无实权,秘书长才是英联邦实际上的掌权者[4][5]。该组织的成员国基本由英国及其旧殖民地组成,也以英式英语为共通语言,但英国的地位并没有凌驾于他国之上,所有成员国一律平等。目前英联邦有56个成员国,其中15个属于英联邦王国,英联邦王国的国家元首、英联邦元首均和英国的一致,即现在的查尔斯三世;另外5个属于独立君主国,它们不以英国君主为自己的元首,而是自立君主,这五国是文莱、斯威士兰、莱索托、马来西亚、汤加;其余的36个均属于共和国,没有君主。

The Commonwealth of Nations, generally known simply as the Commonwealth,[3] is a political association of 53 member states, nearly all of them former territories of the British Empire.[4] The chief institutions of the organisation are the Commonwealth Secretariat, which focuses on intergovernmental aspects, and the Commonwealth Foundation, which focuses on non-governmental relations between member states.[5]

The Commonwealth dates back to the first half of the 20th century with the decolonisation of the British Empire through increased self-governance of its territories. It was originally created as the British Commonwealth of Nations[6] through the Balfour Declaration at the 1926 Imperial Conference, and formalised by the United Kingdom through the Statute of Westminster in 1931. The current Commonwealth of Nations was formally constituted by the London Declaration in 1949, which modernised the community and established the member states as "free and equal".[7]

The human symbol of this free association is the Head of the Commonwealth, currently Queen Elizabeth II, and the 2018 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting appointed Charles, Prince of Wales to be her designated successor, although the position is not technically hereditary. The Queen is the head of state of 16 member states, known as the Commonwealth realms, while 32 other members are republics and five others have different monarchs.

Member states have no legal obligations to one another, but are connected through their use of the English language and historical ties. Their stated shared values of democracy, human rights and the rule of law are enshrined in the Commonwealth Charter[8] and promoted by the quadrennial Commonwealth Games.

The countries of the Commonwealth cover more than 29,958,050 km2 (11,566,870 sq mi), equivalent to 20% of the world's land area, and span all six inhabited continents.

Le Commonwealth ou Commonwealth of Nations (littéralement, la « Communauté des Nations ») est une organisation intergouvernementale composée de 53 États membres qui sont presque tous d'anciens territoires de l'Empire britannique.

Le Commonwealth a émergé au milieu du XXe siècle pendant le processus de décolonisation. Il est formellement constitué par la Déclaration de Londres de 1949 qui fait des États membres des partenaires « libres et égaux ». Le symbole de cette libre association est la reine Élisabeth II qui est chef du Commonwealth. La reine est également le chef d'État monarchique des 16 royaumes du Commonwealth. Les autres États membres sont 32 républiques et cinq monarchies dont le monarque est différent.

Les États membres n'ont aucune obligation les uns envers les autres. Ils sont réunis par la langue, l'histoire et la culture et des valeurs décrites dans la Charte du Commonwealth telles que la démocratie, les droits humains et l'état de droit.

Les États du Commonwealth couvrent 29 958 050 km2 de territoire sur les cinq continents habités. Sa population est estimée à 2,328 milliards d'habitants.

Il Commonwealth delle Nazioni o Commonwealth (acronimo CN) è un'organizzazione intergovernativa di 53 Stati membri indipendenti, tutti accomunati, eccetto il Mozambico e il Ruanda, da un passato storico di appartenenza all'Impero britannico, del quale il Commonwealth è una sorta di sviluppo su base volontaria. La popolazione complessiva degli stati che vi aderiscono è di oltre due miliardi di persone. La parola Commonwealth deriva dall'unione di common (comune) e wealth (benessere), cioè benessere comune.

In passato fu noto anche come Commonwealth britannico, benché tale definizione esistette formalmente solo dalla fondazione nel 1926 fino al 1948.

La Mancomunidad de Naciones (en inglés: Commonwealth of Nations)?, antiguamente Mancomunidad Británica de Naciones (British Commonwealth of Nations), es una organización compuesta por 53 países soberanos independientes y semi independientes que, con la excepción de Mozambique y Ruanda,1 comparten lazos históricos con el Reino Unido. Su principal objetivo es la cooperación internacional en el ámbito político y económico, y desde 1950 la pertenencia a ella no implica sumisión alguna a la Corona británica, aunque se respeta la figura de la reina del Reino Unido. Con el ingreso de Mozambique, la organización ha favorecido el término Mancomunidad de Naciones para subrayar su carácter internacionalista. Sin embargo, el adjetivo británico se sigue utilizando con frecuencia para diferenciarla de otras mancomunidades existentes a nivel internacional.

La reina Isabel II del Reino Unido es la cabeza de la organización, según los principios de la Mancomunidad, «símbolo de la libre asociación de sus miembros».

Содру́жество на́ций (англ. Commonwealth of Nations, до 1946 года — Британское Содружество наций — англ. British Commonwealth of Nations), кратко именуемое просто Содружество (англ. The Commonwealth) — добровольное объединение суверенных государств, в которое входят Великобритания и почти все её бывшие доминионы, колонии и протектораты. Членами Содружества также являются Мозамбик, Руанда, Намибия и Камерун[2].

History

History

Animal world

Animal world

Geography

Geography