Deutsch-Chinesische Enzyklopädie, 德汉百科

Türkei

Türkei

Abdullah ibn Abd al-Aziz

Abdullah ibn Abd al-Aziz

Abe Shinzō

Abe Shinzō

African Union

African Union

Robert Mugabe

Robert Mugabe

Angela Merkel

Angela Merkel

Barack Obama

Barack Obama

David Cameron

David Cameron

Dilma Rousseff

Dilma Rousseff

Donald Tusk

Donald Tusk

Enrique Peña Nieto

Enrique Peña Nieto

Financial Stability Board,FSB

Financial Stability Board,FSB

Mark Carney

Mark Carney

Finanz

Finanz

Food and Agriculture Organization,FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization,FAO

José Graziano da Silva

José Graziano da Silva

Generalsekretär der Vereinten Nationen

Generalsekretär der Vereinten Nationen

Ban Ki-moon

Ban Ki-moon

Hand in Hand

Hand in Hand

Ilham Aliyev

Ilham Aliyev

Internationaler Währungsfonds

Internationaler Währungsfonds

Christine Lagarde

Christine Lagarde

Jacob Zuma

Jacob Zuma

Jean-Claude Juncker

Jean-Claude Juncker

Joko Widodo

Joko Widodo

Justin Trudeau

Justin Trudeau

Lee Hsien Loong

Lee Hsien Loong

Macky Sall

Macky Sall

Malcolm Turnbull

Malcolm Turnbull

Mariano Rajoy

Mariano Rajoy

Matteo Renzi

Matteo Renzi

Najib Razak

Najib Razak

Narendra Modi

Narendra Modi

OECD

OECD

José Ángel Gurría

José Ángel Gurría

Park Geun-hye

Park Geun-hye

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

Robert Mugabe

Robert Mugabe

Türkei

Türkei

Weltbank

Weltbank

Jim Yong Kim

Jim Yong Kim

Wirtschaft und Handel

Wirtschaft und Handel

Wladimir Wladimirowitsch Putin

Wladimir Wladimirowitsch Putin

World Trade Organization

World Trade Organization

Roberto Azevêdo

Roberto Azevêdo

Xi Jingping

Xi Jingping

Türkei

Türkei

UEFA Champions League 2015/16

UEFA Champions League 2015/16

UEFA Champions League 2018/19

UEFA Champions League 2018/19

Gruppe D

Gruppe D

UEFA Champions League 2019/20

UEFA Champions League 2019/20

Gruppe A

Gruppe A

UEFA Champions League 2025/26

UEFA Champions League 2025/26

加济安泰普(Gaziantep),又名安泰普,是土耳其的一座城市,也是仍有人居住的世界上最古老的城市之一,可追溯到前3650年[2]。截至2010年,加济安泰普的城市圈范围包括整个加济安泰普省,人口达到130万,由此也成为土耳其第六大城市。

Gaziantep (arabisch عينتاب, DMG ʿAyintāb oder عنتاب / ʿAntāb, armenisch Այնթա Aynt’ap, kurdisch Entep bzw. Dîlok), auch kurz Antep genannt, ist eine Stadt in Südostanatolien und Hauptstadt der gleichnamigen Provinz. Mit etwa 2,1 Mio. Einwohnern (Stand 2019) ist sie die sechstgrößte Stadt der Türkei. Neben Türken und Kurden leben auch Araber in Gaziantep.

Bangladesh

Bangladesh

China

China

Guangdong Sheng-GD

Guangdong Sheng-GD

Indien

Indien

Indonesien

Indonesien

Iran

Iran

Malaysia

Malaysia

Nepal

Nepal

Niederlande

Niederlande

Pakistan

Pakistan

Portugal

Portugal

Spanien

Spanien

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

Türkei

Türkei

Veneto

Veneto

Vereinigtes Königreich

Vereinigtes Königreich

香料贸易在人类历史上有着举足轻重的作用,尤其是中世纪的欧洲,对香料的渴望直接催生了地理大发现。从遥远的东方运送香辛料到欧洲的贸易线路被称为香料之路。香料作为当时最贵重的商品之一,其价值几与黄金相当。英语中“Spice”(香辛料)这个词来源于拉丁语“species”,常用来指代贵重但量小的物品。

在16世纪,葡萄牙统治了东印度的香料贸易,17世纪的霸主是荷兰,而18世纪则是英国。而在16~19世纪初,中国大陆是世界上最大的香料市场,东南亚大部分香料都销往这里;而荷兰、英国、美国等国商人,就由广州运载中国香料返国,广州成为早期东南亚香料的集散中心[1]。

Der Gewürzhandel umfasste historische Zivilisationen in Asien, Nordostafrika und Europa. Gewürze wie Zimt, Kassia, Kardamom, Ingwer, Pfeffer, Muskatnuss, Sternanis, Nelken und Kurkuma waren bereits in der Antike bekannt und wurden in der östlichen Welt gehandelt. Diese Gewürze fanden ihren Weg in den Nahen Osten noch vor Beginn der christlichen Zeitrechnung, wobei fantastische Geschichten ihre wahre Herkunft verschleierten.

Der maritime Aspekt des Handels wurde von den austronesischen Völkern in Südostasien dominiert, nämlich den alten indonesischen Seefahrern, die bis 1500 v. Chr. Routen von Südostasien nach Sri Lanka und Indien (und später nach China) etablierten. [2] Diese Waren wurden dann von indischen und persischen Händlern über die Weihrauchroute und die römisch-indischen Routen auf dem Landweg zum Mittelmeer und in die griechisch-römische Welt transportiert. Die maritimen Handelswege der Austronesier dehnten sich später bis ins 1. Jahrtausend n. Chr. auf den Nahen Osten und Ostafrika aus, was zur austronesischen Kolonisierung Madagaskars führte.

The spice trade involved historical civilizations in Asia, Northeast Africa and Europe. Spices, such as cinnamon, cassia, cardamom, ginger, pepper, nutmeg, star anise, clove, and turmeric, were known and used in antiquity and traded in the Eastern World.[1] These spices found their way into the Near East before the beginning of the Christian era, with fantastic tales hiding their true sources.[1]

The maritime aspect of the trade was dominated by the Austronesian peoples in Southeast Asia, namely the ancient Indonesian sailors who established routes from Southeast Asia to Sri Lanka and India (and later China) by 1500 BC.[2] These goods were then transported by land toward the Mediterranean and the Greco-Roman world via the incense route and the Roman–India routes by Indian and Persian traders.[3] The Austronesian maritime trade lanes later expanded into the Middle East and eastern Africa by the 1st millennium AD, resulting in the Austronesian colonization of Madagascar.

Within specific regions, the Kingdom of Axum (5th century BC – 11th century AD) had pioneered the Red Sea route before the 1st century AD. During the first millennium AD, Ethiopians became the maritime trading power of the Red Sea. By this period, trade routes existed from Sri Lanka (the Roman Taprobane) and India, which had acquired maritime technology from early Austronesian contact. By the mid-7th century AD, after the rise of Islam, Arab traders started plying these maritime routes and dominated the western Indian Ocean maritime routes.[citation needed]

Arab traders eventually took over conveying goods via the Levant and Venetian merchants to Europe until the rise of the Seljuk Turks in 1090. Later the Ottoman Turks held the route again by 1453 respectively. Overland routes helped the spice trade initially, but maritime trade routes led to tremendous growth in commercial activities to Europe. [citation needed]

The trade was changed by the Crusades and later the European Age of Discovery,[4] during which the spice trade, particularly in black pepper, became an influential activity for European traders.[5] From the 11th to the 15th centuries, the Italian maritime republics of Venice and Genoa monopolized the trade between Europe and Asia.[6] The Cape Route from Europe to the Indian Ocean via the Cape of Good Hope was pioneered by the Portuguese explorer navigator Vasco da Gama in 1498, resulting in new maritime routes for trade.[7]

This trade, which drove world trade from the end of the Middle Ages well into the Renaissance,[5] ushered in an age of European domination in the East.[7] Channels such as the Bay of Bengal served as bridges for cultural and commercial exchanges between diverse cultures[4] as nations struggled to gain control of the trade along the many spice routes.[1] In 1571 the Spanish opened the first trans-Pacific route between its territories of the Philippines and Mexico, served by the Manila Galleon. This trade route lasted until 1815. The Portuguese trade routes were mainly restricted and limited by the use of ancient routes, ports, and nations that were difficult to dominate. The Dutch were later able to bypass many of these problems by pioneering a direct ocean route from the Cape of Good Hope to the Sunda Strait in Indonesia.

Albanien

Albanien

Aleksandar Vučić

Aleksandar Vučić

Alexander De Croo

Alexander De Croo

Alexander Stubb

Alexander Stubb

Andorra

Andorra

Andrej Plenković

Andrej Plenković

Armenien

Armenien

Aserbaidschan

Aserbaidschan

Belgien

Belgien

Bjarni Benediktsson

Bjarni Benediktsson

Bosnien-Herzegowina

Bosnien-Herzegowina

Bulgarien

Bulgarien

Charles Michel

Charles Michel

Dänemark

Dänemark

Denis Bećirović

Denis Bećirović

Deutschland

Deutschland

Dick Schoof

Dick Schoof

Donald Tusk

Donald Tusk

Edi Rama

Edi Rama

Emmanuel Macron

Emmanuel Macron

England

England

Estland

Estland

Europäische Union

Europäische Union

Evika Siliņa

Evika Siliņa

Finnland

Finnland

Frankreich

Frankreich

Georgien

Georgien

Giorgia Meloni

Giorgia Meloni

Gitanas Nausėda

Gitanas Nausėda

Griechenland

Griechenland

Hristijan Mickoski

Hristijan Mickoski

Ilham Aliyev

Ilham Aliyev

Irland

Irland

Island

Island

Italien

Italien

Jakov Milatović

Jakov Milatović

Jens Stoltenberg

Jens Stoltenberg

Jonas Gahr Støre

Jonas Gahr Støre

Kaja Kallas

Kaja Kallas

Keir Starmer

Keir Starmer

Klaus Johannis

Klaus Johannis

Kosovo

Kosovo

Kroatien

Kroatien

Kyriakos Mitsotakis

Kyriakos Mitsotakis

Lettland

Lettland

Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein

Litauen

Litauen

Luc Frieden

Luc Frieden

Luxemburg

Luxemburg

Maia Sandu

Maia Sandu

Malta

Malta

Mette Frederiksen

Mette Frederiksen

Moldawien

Moldawien

Monaco

Monaco

Montenegro

Montenegro

Niederlande

Niederlande

Nikol Paschinjan

Nikol Paschinjan

Nordmazedonien

Nordmazedonien

Norwegen

Norwegen

Olaf Scholz

Olaf Scholz

Österreich

Österreich

Parteien und Regierung

Parteien und Regierung

Parteien und Regierung

Parteien und Regierung

Gipfel der Europäischen Politischen Gemeinschaft

Gipfel der Europäischen Politischen Gemeinschaft

Pedro Sánchez

Pedro Sánchez

Petr Fiala

Petr Fiala

Polen

Polen

Portugal

Portugal

Robert Abela

Robert Abela

Robert Golob

Robert Golob

Rumänien

Rumänien

Rumen Radew

Rumen Radew

San Marino

San Marino

Schweden

Schweden

Schweiz

Schweiz

Serbien

Serbien

Simon Harris

Simon Harris

Slowakei

Slowakei

Slowenien

Slowenien

Spanien

Spanien

Tschechien

Tschechien

Türkei

Türkei

Ukraine

Ukraine

Ungarn

Ungarn

Vereinigtes Königreich

Vereinigtes Königreich

Viktor Orbán

Viktor Orbán

Viola Amherd

Viola Amherd

Wolodymyr Selenskyj

Wolodymyr Selenskyj

Zypern

Zypern

Aljaksandr Lukaschenka

Aljaksandr Lukaschenka

Aserbaidschan

Aserbaidschan

Belarus

Belarus

China

China

Emomalij Rahmon

Emomalij Rahmon

Indien

Indien

Iran

Iran

Kasachstan

Kasachstan

Kirgisistan

Kirgisistan

Mohammad Mokhber

Mohammad Mokhber

Mongolei

Mongolei

Pakistan

Pakistan

Qassym-Schomart Toqajew

Qassym-Schomart Toqajew

Russland

Russland

Sadyr Dschaparow

Sadyr Dschaparow

Shavkat Mirziyoyev

Shavkat Mirziyoyev

Shehbaz Sharif

Shehbaz Sharif

Tadschikistan

Tadschikistan

Türkei

Türkei

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan

Usbekistan

Usbekistan

Wirtschaft und Handel

Wirtschaft und Handel

Wladimir Wladimirowitsch Putin

Wladimir Wladimirowitsch Putin

Xi Jingping

Xi Jingping

The 2024 SCO summit was the 24th annual summit of heads of state of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation held between 3 and 4 July 2024 in Astana, Kazakhstan.

2024 年上海合作组织峰会是上海合作组织第二十四次元首年度峰会,于 2024 年 7 月 3 日至 4 日在哈萨克斯坦阿斯塔纳举行。

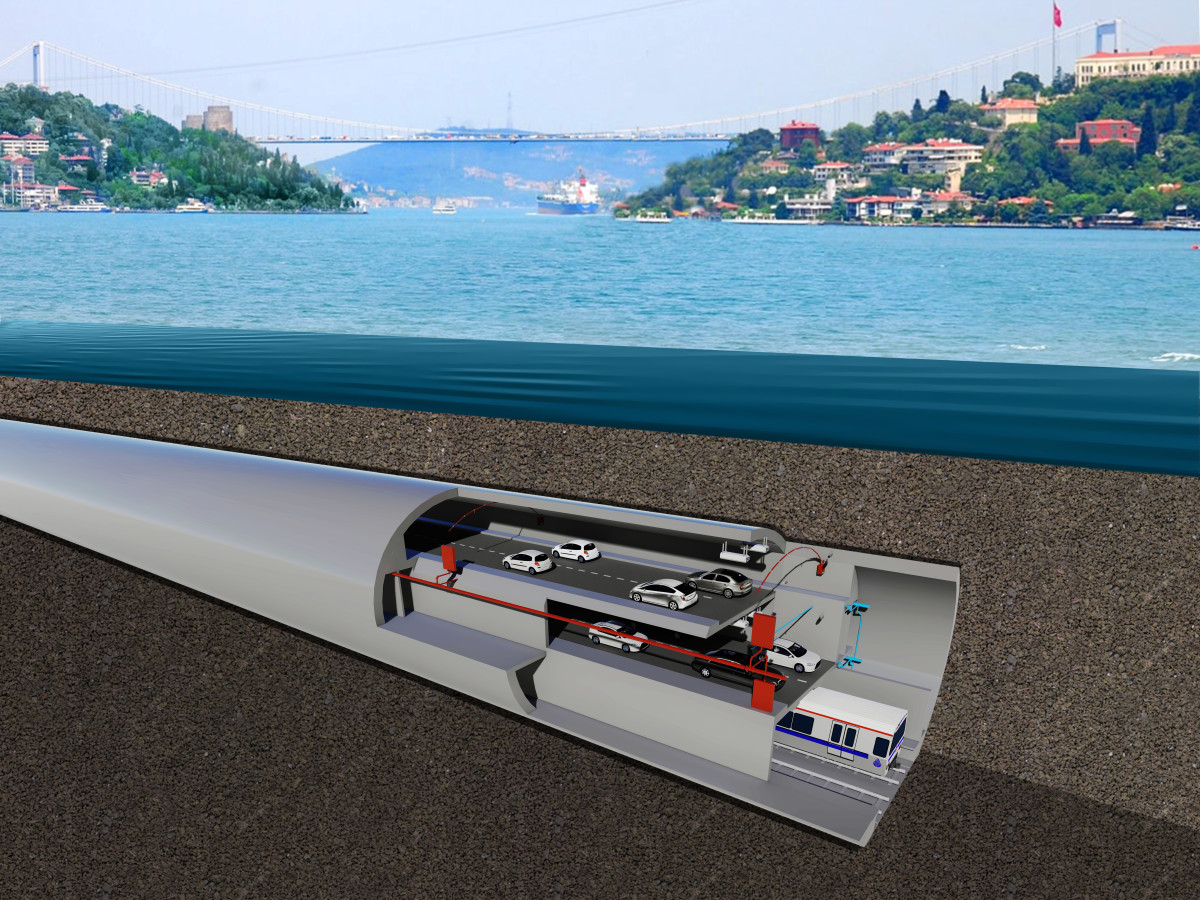

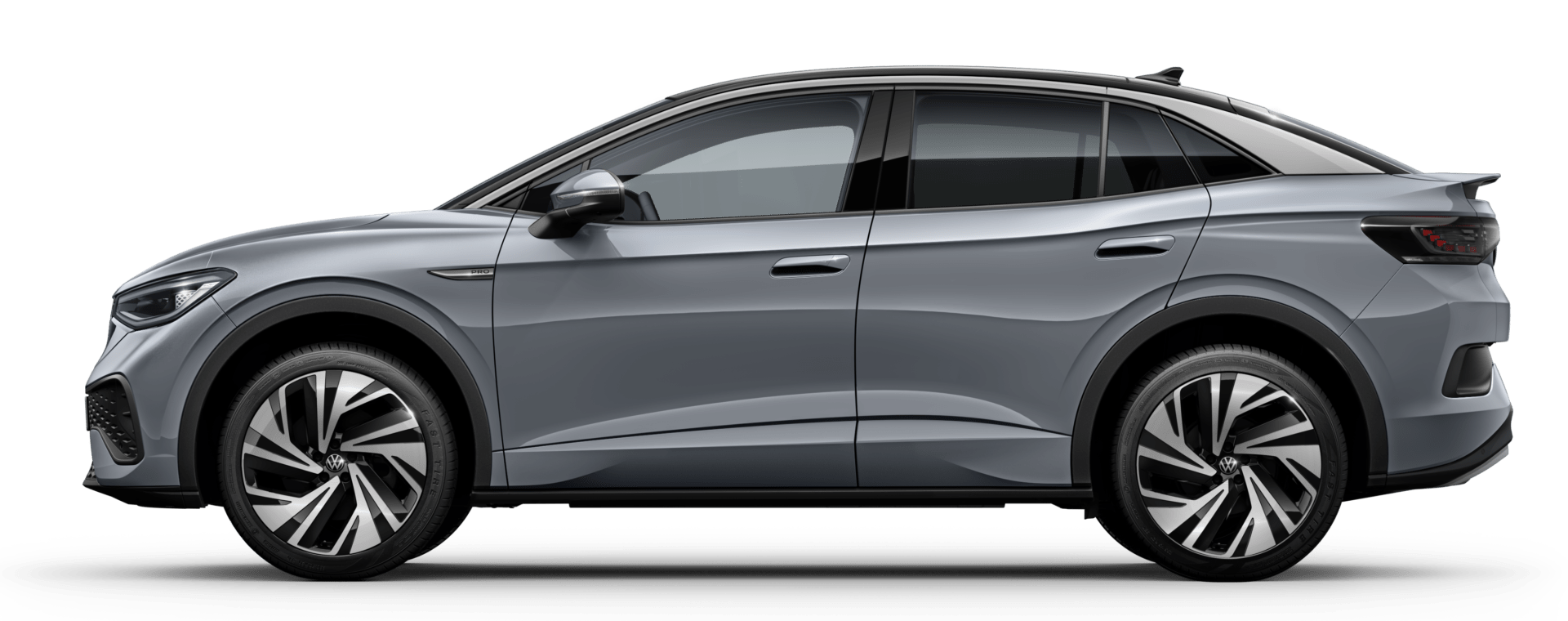

Automobil

Automobil

Unternehmen

Unternehmen

Sport

Sport

Internationale Städte

Internationale Städte

Geschichte

Geschichte

Weltkulturerbe

Weltkulturerbe

Zivilisation

Zivilisation

Geographie

Geographie