Deutsch-Chinesische Enzyklopädie, 德汉百科

Jilin Sheng-JL

Jilin Sheng-JL

Beijing Shi-BJ

Beijing Shi-BJ

Belarus

Belarus

Berlin

Berlin

Brandenburg

Brandenburg

Bremen

Bremen

China

China

Germany

Germany

France

France

Gansu Sheng-GS

Gansu Sheng-GS

Hamburg

Hamburg

Hebei Sheng-HE

Hebei Sheng-HE

Heilongjiang Sheng-HL

Heilongjiang Sheng-HL

Henan Sheng-HA

Henan Sheng-HA

Hubei Sheng-HB

Hubei Sheng-HB

Hunan Sheng-HN

Hunan Sheng-HN

Iran

Iran

Italy

Italy

Jilin Sheng-JL

Jilin Sheng-JL

Kasachstan

Kasachstan

Liaoning Sheng-LN

Liaoning Sheng-LN

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Netherlands

Netherlands

Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

North Rhine-Westphalia

North Rhine-Westphalia

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Russia

Russia

Saxony

Saxony

Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shandong Sheng-SD

Shandong Sheng-SD

Shanxi Sheng-SX

Shanxi Sheng-SX

Sichuan Sheng-SC

Sichuan Sheng-SC

Spain

Spain

Turkey

Turkey

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

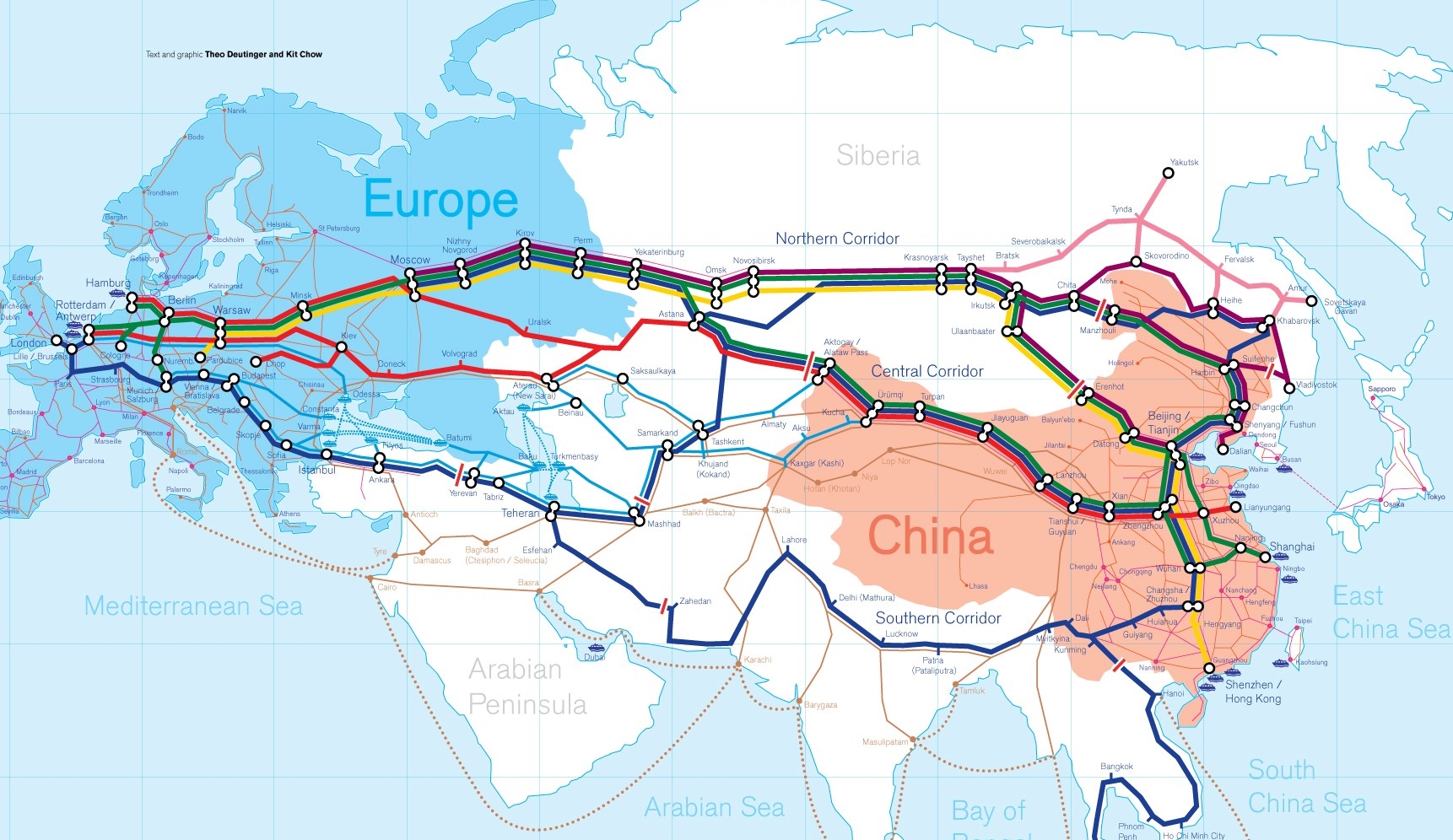

Die Neue eurasische Kontinentalbrücke (chinesisch 新亚欧大陆桥, Pinyin Xīn Yà-Ōu Dàlù Qiáo, englisch New Eurasian Continental Bridge), die auch Zweite eurasische Kontinentalbrücke (第二亚欧大陆桥, Dì'èr Yà-Ōu Dàlù Qiáo, englisch Second Eurasian Continental Bridge) genannt wird, ist eine 10.870 Kilometer[1] lange Eisenbahnverbindung, die Rotterdam in Europa mit der ostchinesischen Hafenstadt Lianyungang in der Provinz Jiangsu verbindet.

Sie besteht seit 1990 und führt durch die Dsungarische Pforte (Grenzbahnhof Alashankou). Die Lan-Xin-Bahn (chinesisch 兰新铁路, Pinyin Lán-Xīn Tiělù), also die Strecke von Lanzhou nach Ürümqi (in Xinjiang), ist ein Teil von ihr.

Es gibt eine nördliche, mittlere und südliche Route.[2] Die mittlere Strecke verläuft durch Kasachstan über Dostyk, Aqtogai, Astana, Samara, Smolensk, Brest, Warschau, Berlin zum Hafen von Rotterdam.[3] Vom slowakischen Košice soll auch eine Abzweigung in den Großraum Wien führen, siehe Breitspurstrecke Košice–Wien.

The New Eurasian Land Bridge, also called the Second or New Eurasian Continental Bridge, is the southern branch of the Eurasian Land Bridge rail links running through China. The Eurasian Land Bridge is the overland rail link between Asia and Europe.

Due to a break-of-gauge between standard gauge used in China and the Russian gauge used in the former Soviet Union countries, containers must be physically transferred from Chinese to Kazakh railway cars at Dostyk on the Chinese-Kazakh border and again at the Belarus-Poland border where the standard gauge used in western Europe begins. This is done with truck-mounted cranes.[1] Chinese media often states that the New Eurasian Land/Continental Bridge extends from Lianyungang to Rotterdam, a distance of 11,870 kilometres (7,380 mi). The exact route used to connect the two cities is not always specified in Chinese media reports, but appears to usually refer to the route which passes through Kazakhstan.

All rail freight from China across the Eurasian Land Bridge must pass north of the Caspian Sea through Russia at some point. A proposed alternative would pass through Turkey and Bulgaria,[2] but any route south of the Caspian Sea must pass through Iran.[1]

Kazakhstan's President Nursultan Nazarbayev urged Eurasian and Chinese leaders at the 18th Shanghai Cooperation Organisation to construct the Eurasian high-speed railway (EHSRW) following a Beijing-Astana-Moscow-Berlin.[3]

The Eurasian Land Bridge (Russian: Евразийский сухопутный мост, Yevraziyskiy sukhoputniy most), sometimes called the New Silk Road (Новый шёлковый путь, Noviy shyolkoviy put'), or Belt and Road Initiative is the rail transport route for moving freight and passengers overland between Pacific seaports in the Russian Far East and China and seaports in Europe. The route, a transcontinental railroad and rail land bridge, currently comprises the Trans-Siberian Railway, which runs through Russia and is sometimes called the Northern East-West Corridor, and the New Eurasian Land Bridge or Second Eurasian Continental Bridge, running through China and Kazakhstan. As of November 2007, about 1% of the $600 billion in goods shipped from Asia to Europe each year were delivered by inland transport routes.[1]

Completed in 1916, the Trans-Siberian connects Moscow with Russian Pacific seaports such as Vladivostok. From the 1960s until the early 1990s the railway served as the primary land bridge between Asia and Europe, until several factors caused the use of the railway for transcontinental freight to dwindle. One factor is that the railways of the former Soviet Union use a wider rail gauge than most of the rest of Europe as well as China. Recently, however, the Trans-Siberian has regained ground as a viable land route between the two continents.[why?]

China's rail system had long linked to the Trans-Siberian via northeastern China and Mongolia. In 1990 China added a link between its rail system and the Trans-Siberian via Kazakhstan. China calls its uninterrupted rail link between the port city of Lianyungang and Kazakhstan the New Eurasian Land Bridge or Second Eurasian Continental Bridge. In addition to Kazakhstan, the railways connect with other countries in Central Asia and the Middle East, including Iran. With the October 2013 completion of the rail link across the Bosphorus under the Marmaray project the New Eurasian Land Bridge now theoretically connects to Europe via Central and South Asia.

Proposed expansion of the Eurasian Land Bridge includes construction of a railway across Kazakhstan that is the same gauge as Chinese railways, rail links to India, Burma, Thailand, Malaysia and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, construction of a rail tunnel and highway bridge across the Bering Strait to connect the Trans-Siberian to the North American rail system, and construction of a rail tunnel between South Korea and Japan. The United Nations has proposed further expansion of the Eurasian Land Bridge, including the Trans-Asian Railway project.

El Nuevo Puente de Tierra de Eurasia es también llamado el Segundo o Nuevo Puente Continental de Eurasia. Es la rama meridional de las conexiones ferroviarias del Puente de Tierra de Eurasia (también conocido como "Nueva Ruta de la Seda") que se extienden a través de la República Popular China, atravesando Kazajistán, Rusia y Bielorrusia. El Puente de Tierra de Eurasia es el enlace ferroviario terrestre entre Asia Oriental y Europa.

La Nueva Ruta de la Seda (en ruso, Новый шёлковый путь, Noviy shyolkoviy put), o Puente Terrestre Euroasiático, es la ruta de transporte ferroviario para el movimiento de tren de mercancías y tren de pasajeros por tierra entre los puertos del Pacífico, en el Lejano Oriente ruso y chino y los puertos marítimos en Europa.

La ruta, un ferrocarril transcontinental y puente terrestre, actualmente comprende el ferrocarril Transiberiano, que se extiende a través de Rusia, y el nuevo puente de tierra de Eurasia o segundo puente continental de Eurasia, que discurre a través de China y Kazajistán, también se van a construir carreteras entre las ciudades de la ruta. A partir de noviembre de 2007, aproximadamente el 1% de los 600 millones de dólares en bienes enviados desde Asia a Europa cada año se entregaron por vías de transporte terrestre.1

Terminado en 1916, el tren Transiberiano conecta Moscú con el lejano puerto de Vladivostok en el océano Pacífico, el más largo del mundo en el Lejano Oriente e importante puerto del Pacífico. Desde la década de 1960 hasta principios de 1990 el ferrocarril sirvió como el principal puente terrestre entre Asia y Europa, hasta que varios factores hicieron que el uso de la vía férrea transcontinental para el transporte de carga disminuyese.

Un factor es que los ferrocarriles de la Unión Soviética utilizan un ancho de vía más ancho en los rieles que la mayor parte del resto de Europa y China, y el transporte en barcos de carga por el canal de Suez en Egipto, construido por Inglaterra. El sistema ferroviario de China se une al Transiberiano en el noreste de China y Mongolia. En 1990 China añadió un enlace entre su sistema ferroviario y el Transiberiano a través de Kazajistán. China denomina a su enlace ferroviario ininterrumpido entre la ciudad portuaria de Lianyungang y Kazajistán como el «Puente terrestre de Nueva Eurasia» o «Segundo puente continental Euroasiático». Además de Kazajistán, los ferrocarriles conectan con otros países de Asia Central y Oriente Medio, incluyendo a Irán. Con la finalización en octubre de 2013 de la línea ferroviaria a través del Bósforo en el marco del proyecto Marmaray el puente de tierra de Nueva Eurasia conecta ahora teóricamente a Europa a través de Asia Central y del Sur.

La propuesta de ampliación del Puente Terrestre Euroasiático incluye la construcción de un ferrocarril a través de Kazajistán con el mismo ancho de vía que los ferrocarriles chinos, enlaces ferroviarios a la India, Birmania, Tailandia, Malasia y otros países del sudeste asiático, la construcción de un túnel ferroviario y un puente de carretera a través del estrecho de Bering para conectar el Transiberiano al sistema ferroviario de América del Norte, y la construcción de un túnel ferroviario entre Corea del Sur y Japón. Las Naciones Unidas ha propuesto una mayor expansión del Puente Terrestre Euroasiático, incluyendo el proyecto del ferrocarril transasiático.

Новый шёлковый путь (Евразийский сухопутный мост — концепция новой паневразийской (в перспективе — межконтинентальной) транспортной системы, продвигаемой Китаем, в сотрудничестве с Казахстаном, Россией и другими странами, для перемещения грузов и пассажиров по суше из Китая в страны Европы. Транспортный маршрут включает трансконтинентальную железную дорогу — Транссибирскую магистраль, которая проходит через Россию и второй Евразийский континентальный мост[en], проходящий через Казахстан[1]. Поезда по этому самому длинному в мире грузовому железнодорожному маршруту из Китая в Германию будут идти 15 дней, что в 2 раза быстрее, чем по морскому маршруту через Суэцкий канал[2].

Идея Нового шёлкового пути основывается на историческом примере древнего Великого шёлкового пути, действовавшего со II в. до н. э. и бывшего одним из важнейших торговых маршрутов в древности и в средние века. Современный НШП является важнейшей частью стратегии развития Китая в современном мире — Новый шёлковый путь не только должен выстроить самые удобные и быстрые транзитные маршруты через центр Евразии, но и усилить экономическое развитие внутренних регионов Китая и соседних стран, а также создать новые рынки для китайских товаров (по состоянию на ноябрь 2007 года, около 1 % от товаров на 600 млрд долл. из Азии в Европу ежегодно доставлялись наземным транспортом[3]).

Китай продвигает проект «Нового шёлкового пути» не просто как возрождение древнего Шёлкового пути, транспортного маршрута между Востоком и Западом, но как масштабное преобразование всей торгово-экономической модели Евразии, и в первую очередь — Центральной и Средней Азии. Китайцы называют эту концепцию — «один пояс — один путь». Она включает в себя множество инфраструктурных проектов, которые должны в итоге опоясать всю планету. Проект всемирной системы транспортных коридоров соединяет Австралию и Индонезию, всю Центральную и Восточную Азию, Ближний Восток, Европу, Африку и через Латинскую Америку выходит к США. Среди проектов в рамках НШП планируются железные дороги и шоссе, морские и воздушные пути, трубопроводы и линии электропередач, и вся сопутствующая инфраструктура. По самым скромным оценкам, НШП втянет в свою орбиту 4,4 миллиарда человек — более половины населения Земли[4].

Предполагаемое расширение Евразийского сухопутного моста включает в себя строительство железнодорожных путей от трансконтинентальных линий в Иран, Индию, Мьянму, Таиланд, Пакистан, Непал, Афганистан и Малайзию, в другие регионы Юго-Восточной Азии и Закавказья (Азербайджан, Грузия). Маршрут включает тоннель Мармарай под проливом Босфор, паромные переправы через Каспийское море (Азербайджан-Иран-Туркменистан-Казахстан) и коридор Север-Юг.Организация Объединенных Наций предложила дальнейшее расширение Евразийского сухопутного моста, в том числе проекта Трансазиатской железной дороги (фактически существует уже в 2 вариантах).

Для развития инфраструктурных проектов в странах вдоль Нового шёлкового пути и Морского Шёлкового пути и с целью содействия сбыту китайской продукции в декабре 2014 года был создан инвестиционный Фонд Шёлкового пути[5].

8 мая 2015 года было подписано совместное заявление Президента РФ В. Путина и Председателя КНР Си Цзиньпина о сотрудничестве России и Китая, в рамках ЕАЭС и трансевразийского торгово-инфраструктурного проекта экономического пояса «Шёлковый путь». 13 июня 2015 года был запущен самый длинный в мире грузовой железнодорожный маршрут Харбин — Гамбург (Германия), через территорию России.

萨满是分布于北美洲和北亚、中亚一类巫觋宗敎,包括满族萨满、蒙古族萨满、中亚萨满、西伯利亚萨满、北美洲萨满。萨满(珊蛮)曾被认为有控制天气、预言、解梦、占星以及旅行到天堂或者地狱的能力。萨满目前最盛行于美国,美音美洲的原住民(尤其是北美洲)非常相信,即使是被基督教的美国征服以后。在亚洲的传统始于史前时代并且遍布世界。最崇拜萨满的地方是伏尔加河流域、芬兰人种居住的地区、东西伯利亚与西西伯利亚。满洲人的祖先女真人,也曾信奉萨满,直到公元11世纪。[1]清代以前一直在中国东北甚至蒙古地区大范围流传,清朝皇帝把萨满和满族的传统结合起来,运用萨满把东北的人民纳入帝国的轨道,同时萨满在清朝的宫廷生活中也找到了位置。目前,满族、鄂温克族等民族有很多信奉萨满的人群,并且有萨满。

Schamanismus bezeichnet:

- Im engen Sinne die traditionellen ethnischen Religionen des Kulturareales Sibirien (Nenzen, Jakuten, Altaier, Burjaten, Ewenken, auch europäische Samen u. a.), bei denen das Vorhandensein von Schamanen von europäischen Forschern der Expansionszeit als wesentliches gemeinsames Kennzeichen erachtet wurde.[1] Zur besseren Abgrenzung werden diese Religionen häufig „klassischer Schamanismus“ oder auch „sibirischer Animismus“ genannt.[2]

- Im weiten Sinne alle wissenschaftlichen Konzepte, die aufgrund von ähnlichen Praktiken spiritueller Spezialisten in verschiedenen traditionellen Gesellschaften die kulturübergreifende Existenz des Schamanismus postulieren. Nach László Vajda[3] und Jane Monnig Atkinson[A 1] sollte aufgrund der Vielzahl unterschiedlicher Konzepte treffender von Schamanismen im Plural gesprochen werden.

Sibirische Schamanen und verschiedene Geisterbeschwörer anderer Ethnien – die ebenfalls häufig verallgemeinernd als Schamanen bezeichnet werden – hatten oder haben in vielen traditionellen Weltanschauungen angeblich Einfluss auf die Mächte des Jenseits. Sie setzten ihre Fähigkeiten vorwiegend zum Wohle der Gemeinschaft ein, um in unlösbar erscheinenden Krisensituationen die „kosmische Harmonie“ zwischen Diesseits und Jenseits wiederherzustellen. In diesem weiten Sinne bezeichnet Schamanismus eine Reihe unscharf bestimmter Phänomene „zwischen Religion und Heilritual“.[4][5][6][7][8][9][Anmerkung 1]

Eine nähere allgemeingültige Bestimmung ist nicht möglich, da die Definition verschiedene Betrachtungsweisen aus Sicht der Ethnologie, Kulturanthropologie, Religionswissenschaften, Archäologie, Soziologie und Psychologie enthält.[10][11] Dies hat unter anderem zur Folge, dass Angaben zur räumlichen und zeitlichen Verbreitung der „Schamanismen“ erheblich voneinander abweichen und in vielen Fällen umstritten sind.[12][13][14] Der amerikanische Ethnologe Clifford Geertz sprach daher bereits in den 1960er Jahren dem „westlich idealistischen Konstrukt Schamanismus“ jeglichen Erklärungswert ab.[A 2]

Einig ist man sich lediglich bei der „engen Definition“ des klassisch sibirischen Schamanismus – dem Ausgangspunkt der ersten „Schamanismen“. Dazu gehört vor allem die genaue Beschreibung der dort praktizierten rituellen Ekstase, eine weitgehend übereinstimmende ethnische Religion sowie eine ähnliche Kosmologie und Lebensweise.[15][11][16]

Nach weiter gefassten Definitionen wird Schamanismus bis in die 1980er Jahre als frühe, kulturübergreifende Entwicklungsstufe jeglicher Religion betrachtet.[15] Vor allem das Konzept des Core-Schamanismus von Michael Harner ist hier zu nennen. Diese Auslegung gilt jedoch mittlerweile als nicht konsensfähig.[14] Seit den 1990er Jahren steht häufig der Aspekt des „Heilens“ im Mittelpunkt des Interesses (und der jeweiligen Definition).[10]

Da bereits der klassische Schamanismus Sibiriens etliche Varianten aufweist, werden weiter reichende geographische oder historische Auslegungen, die solche Phänomene aus ihrem kulturellen Kontext gelöst betrachten und verallgemeinern, von vielen Autoren als spekulativ kritisiert.[17][13] In der zeitgenössischen Literatur – populärwissenschaftlichen (insbesondere esoterischen) Büchern, aber auch wissenschaftlichen Schriften – wird in diesem Zusammenhang oftmals nicht deutlich gemacht, auf welche Ethnien sich Darstellungen zu bestimmten schamanischen Praktiken konkret beziehen, so dass regionale (oft sibirische) Phänomene auch in anderen Kulturen verortet werden, in deren Traditionen sie tatsächlich jedoch fremd sind. Beispiele dafür sind der Weltenbaum und die gesamte schamanische Kosmologie: in Eurasien verankerte mythologische Konzepte, die hier mit ähnlichen Archetypen anderer Weltgegenden gleichgesetzt werden und so das irreführende Bild eines einheitlichen Schamanismus erzeugen.[13]

Insbesondere die äußerst erfolgreichen Bücher von Eliade, Castañeda und Harner haben den „modernen Mythos Schamanismus“ erzeugt, der suggeriert, dass es sich dabei um ein universelles und homolog entstandenes religiös-spirituelles Phänomen handeln würde. Im Hinblick auf das große Interesse in der Bevölkerung[18] weisen einige Autoren darauf hin, dass Schamanismus keine einheitliche Ideologie oder Religion bestimmter Kulturen ist, sondern um ein wissenschaftliches Konstrukt aus eurozentrischer Perspektive handelt, um ähnliche Phänomene rund um die Geisterbeschwörer unterschiedlichster Herkunft zu vergleichen und zu klassifizieren.[14][19][20]

シャーマニズムあるいはシャマニズム(英: Shamanism)とは、シャーマン(巫師・祈祷師)の能力により成立している宗教や宗教現象の総称であり[1]、宗教学、民俗学、人類学(宗教人類学、文化人類学)等々で用いられている用語・概念である[1]。巫術(ふじゅつ)などと表記されることもある[1]。

シャーマニズムとはシャーマンを中心とする宗教形態で、精霊や冥界の存在が信じられている。シャーマニズムの考えでは、霊の世界は物質界よりも上位にあり、物質界に影響を与えているとされる[2]。

シャーマンとはトランス状態に入って超自然的存在(霊、神霊、精霊、死霊など)と交信する現象を起こすとされる職能・人物のことである[1]。 「シャーマン」という用語・概念は、ツングース語で呪術師の一種を指す「šaman, シャマン」に由来し[1][注釈 1]、19世紀以降に民俗学者や旅行家、探検家たちによって、極北や北アジアの呪術あるいは宗教的職能者一般を呼ぶために用いられるようになり、その後に宗教学、民俗学、人類学などの学問領域でも類似現象を指すための用語(学術用語)として用いられるようになったものである[1]。

Shamanism is a practice that involves a practitioner reaching altered states of consciousness in order to perceive and interact with what they believe to be a spirit world and channel these transcendental energies into this world.[1]

A shaman (/ˈʃɑːmən/ SHAH-men, /ˈʃæmən/ or /ˈʃeɪmən/)[2] is someone who is regarded as having access to, and influence in, the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits, who typically enters into a trance state during a ritual, and practices divination and healing.[2] The word "shaman" probably originates from the Tungusic Evenki language of North Asia. According to ethnolinguist Juha Janhunen, "the word is attested in all of the Tungusic idioms" such as Negidal, Lamut, Udehe/Orochi, Nanai, Ilcha, Orok, Manchu and Ulcha, and "nothing seems to contradict the assumption that the meaning 'shaman' also derives from Proto-Tungusic" and may have roots that extend back in time at least two millennia.[3] The term was introduced to the west after Russian forces conquered the shamanistic Khanate of Kazan in 1552.

The term "shamanism" was first applied by Western anthropologists as outside observers of the ancient religion of the Turks and Mongols, as well as those of the neighbouring Tungusic and Samoyedic-speaking peoples. Upon observing more religious traditions across the world, some Western anthropologists began to also use the term in a very broad sense. The term was used to describe unrelated magico-religious practices found within the ethnic religions of other parts of Asia, Africa, Australasia and even completely unrelated parts of the Americas, as they believed these practices to be similar to one another.[4]

Mircea Eliade writes, "A first definition of this complex phenomenon, and perhaps the least hazardous, will be: shamanism = 'technique of religious ecstasy'."[5] Shamanism encompasses the premise that shamans are intermediaries or messengers between the human world and the spirit worlds. Shamans are said to treat ailments/illness by mending the soul. Alleviating traumas affecting the soul/spirit restores the physical body of the individual to balance and wholeness. The shaman also enters supernatural realms or dimensions to obtain solutions to problems afflicting the community. Shamans may visit other worlds/dimensions to bring guidance to misguided souls and to ameliorate illnesses of the human soul caused by foreign elements. The shaman operates primarily within the spiritual world, which in turn affects the human world. The restoration of balance results in the elimination of the ailment.[5]

Beliefs and practices that have been categorised this way as "shamanic" have attracted the interest of scholars from a wide variety of disciplines, including anthropologists, archaeologists, historians, religious studies scholars, philosophers and psychologists. Hundreds of books and academic papers on the subject have been produced, with a peer-reviewed academic journal being devoted to the study of shamanism. In the 20th century, many Westerners involved in the counter-cultural movement have created modern magico-religious practices influenced by their ideas of indigenous religions from across the world, creating what has been termed neoshamanism or the neoshamanic movement.[6] It has affected the development of many neopagan practices, as well as faced a backlash and accusations of cultural appropriation,[7] exploitation and misrepresentation when outside observers have tried to represent cultures they do not belong to.[8][9]

Le chamanisme est une pratique centrée sur la médiation entre les êtres humains et les esprits de la nature ou les âmes du gibier, les morts du clan, les âmes des enfants à naître, les âmes des malades à guérir, la communication avec des divinités, etc. C'est le chamane qui incarne cette fonction, dans le cadre d'une interdépendance étroite avec la communauté qui le reconnaît comme tel.

Le chamanisme, au sens strict (chamane vient étymologiquement de la langue toungouse), prend sa source dans les sociétés traditionnelles sibériennes. Partie de la Sibérie, la pensée chamanique a essaimé de la Baltique à l'Extrême-Orient et a sans doute franchi le détroit de Béring avec les premiers Amérindiens. On observe des pratiques analogues chez de nombreux peuples, à commencer par les Mongols, les Turcs et les Magyars1 (avant leur christianisation), qui seraient tous originaires de Sibérie, mais aussi au Népal, en Chine, en Corée, au Japon, chez les Scandinaves, chez les Amérindiens d'Amérique du Nord, en Afrique, en Australie, chez les Amérindiens d'Amérique latine2 et également chez les Celtes (druidisme orthodoxe).

Sciamanesimo (o sciamanismo) indica, nella storia delle religioni, in antropologia culturale e in etnologia, un insieme di credenze, pratiche religiose, tecniche magico-rituali, estatiche ed etnomediche riscontrabili in varie culture e tradizioni[1].

El chamanismo se refiere a una clase de creencias y prácticas tradicionales similares al animismo que aseguran la capacidad de diagnosticar y de curar el sufrimiento del ser humano, y en algunas sociedades, la capacidad de causarlo. Los chamanes creen lograrlo contactando con el mundo de los espíritus y formando una relación especial con ellos. Aseguran tener la capacidad de controlar el tiempo, profetizar, interpretar los sueños, usar la proyección astral y viajar a los mundos superior e inferior. Las tradiciones de chamanismo han existido en todo el mundo desde épocas prehistóricas.

Algunos especialistas en antropología definen al chamán como un intermediario entre el mundo natural y espiritual, que viaja entre los mundos en un estado de trance. Una vez en el mundo de los espíritus, se comunica con ellos para conseguir ayuda en la curación, la caza o el control del tiempo. Michael Ripinsky-Naxon describe a los chamanes como «personas que tienen fuerte ascendencia en su ambiente circundante y en la sociedad de la que forman parte».

Un segundo grupo de antropólogos discuten el término chamanismo, señalando que es una palabra para una institución cultural específica que, al incluir a cualquier sanador de cualquier sociedad tradicional, produce una uniformidad falsa entre estas culturas y crea la idea equívoca de la existencia de una religión anterior a todas los demás. Otros les acusan de ser incapaces de reconocer las concordancias entre las diversas sociedades tradicionales.

El chamanismo se basa en la premisa de que el mundo visible está impregnado por fuerzas y espíritus invisibles de dimensiones paralelas que coexisten simultáneamente con la nuestra, que afectan todas a las manifestaciones de la vida. En contraste con el animismo, en el que todos y cada uno de los miembros de la sociedad implicada lo practica, el chamanismo requiere conocimientos o capacidades especializados. Se podría decir que los chamanes son los expertos empleados por los animistas o las comunidades animistas. Sin embargo, los chamanes no se organizan en asociaciones rituales o espirituales, como hacen los sacerdotes.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan

Egypt

Egypt

Argentina

Argentina

Armenia

Armenia

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan

Bangladesh

Bangladesh

Beijing Shi-BJ

Beijing Shi-BJ

Belarus

Belarus

Belgium

Belgium

Amber Road

Amber Road

Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Chile

Chile

China

China

Chongqing Shi-CQ

Chongqing Shi-CQ

Germany

Germany

Eritrea

Eritrea

Fidschi

Fidschi

France

France

Fujian Sheng-FJ

Fujian Sheng-FJ

Gansu Sheng-GS

Gansu Sheng-GS

Georgia

Georgia

Greece

Greece

Guangdong Sheng-GD

Guangdong Sheng-GD

Guangxi Zhuangzu Zizhiqu-GX

Guangxi Zhuangzu Zizhiqu-GX

Hainan Sheng-HI

Hainan Sheng-HI

Hand in Hand

Hand in Hand

Hebei Sheng-HE

Hebei Sheng-HE

Heilongjiang Sheng-HL

Heilongjiang Sheng-HL

Henan Sheng-HA

Henan Sheng-HA

Hongkong Tebiexingzhengqu-HK

Hongkong Tebiexingzhengqu-HK

India

India

Indonesia

Indonesia

Iraq

Iraq

Iran

Iran

Italy

Italy

Japan

Japan

Yemen

Yemen

Jiangsu Sheng-JS

Jiangsu Sheng-JS

Jiangxi Sheng-JX

Jiangxi Sheng-JX

Jilin Sheng-JL

Jilin Sheng-JL

Jordan

Jordan

Cambodia

Cambodia

Kasachstan

Kasachstan

Kenya

Kenya

Kenya

Kenya

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan

Laos

Laos

Liaoning Sheng-LN

Liaoning Sheng-LN

Madagaskar

Madagaskar

Malaysia

Malaysia

Mongolei

Mongolei

Myanmar

Myanmar

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Nepal

Nepal

Netherlands

Netherlands

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Oman

Oman

Austria

Austria

Pakistan

Pakistan

Philippines

Philippines

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Qinghai Sheng-QH

Qinghai Sheng-QH

Republic of Korea

Republic of Korea

Republic of the Sudan

Republic of the Sudan

Russia

Russia

Switzerland

Switzerland

Silk road

Silk road

Serbia

Serbia

Serbia

Serbia

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shanghai Shi-SH

Shanghai Shi-SH

Sichuan Sheng-SC

Sichuan Sheng-SC

Singapore

Singapore

Slovakia

Slovakia

Somalia

Somalia

Spain

Spain

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka

South Africa

South Africa

Syria

Syria

Tajikistan

Tajikistan

Taiwan Sheng-TW

Taiwan Sheng-TW

Tianjin Shi-TJ

Tianjin Shi-TJ

Czech Republic

Czech Republic

Czech Republic

Czech Republic

Turkey

Turkey

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan

Ukraine

Ukraine

Hungary

Hungary

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Vietnam

Vietnam

World Heritage

World Heritage

Economy and trade

Economy and trade

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

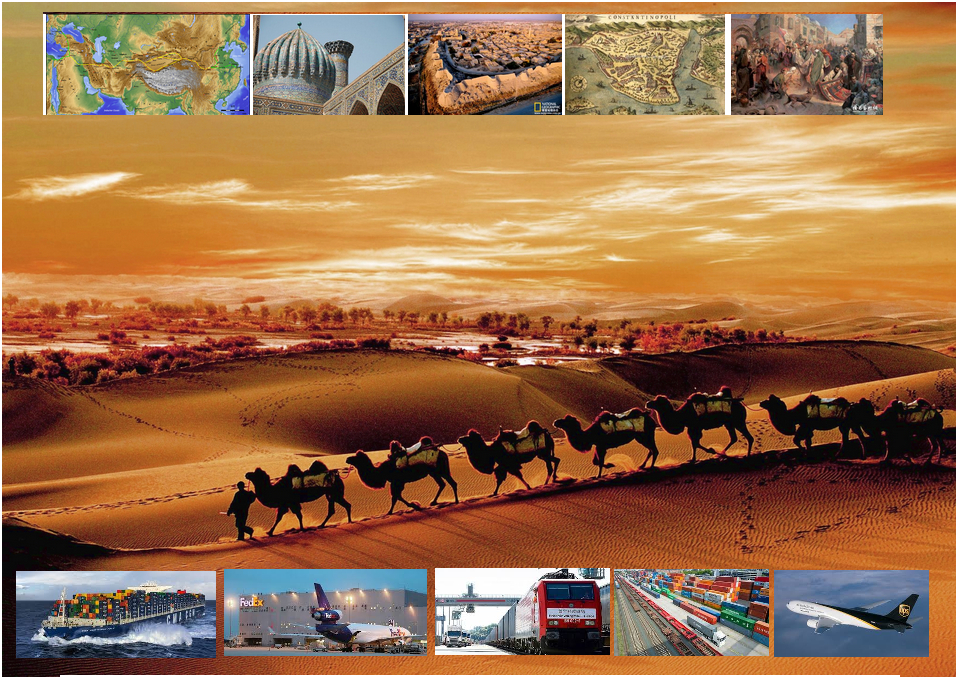

丝绸之路(德语:Seidenstraße;英语:Silk Road),常简称为丝路,此词最早来自于德意志帝国地理学家费迪南·冯·李希霍芬男爵于1877年出版的一套五卷本的地图集。[1]

丝绸之路通常是指欧亚北部的商路,与南方的茶马古道形成对比,西汉时张骞以长安为起点,经关中平原、河西走廊、塔里木盆地,到锡尔河与乌浒河之间的中亚河中地区、大伊朗,并联结地中海各国的陆上通道。这条道路也被称为“陆路丝绸之路”,以区别日后另外两条冠以“丝绸之路”名称的交通路线。因为由这条路西运的货物中以丝绸制品的影响最大,故得此名。其基本走向定于两汉时期,包括南道、中道、北道三条路线。但实际上,丝绸之路并非是一条 “路”,而是一个穿越山川沙漠且没有标识的道路网络,并且丝绸也只是货物中的一种。[1]:5

广义的丝绸之路指从上古开始陆续形成的,遍及欧亚大陆甚至包括北非和东非在内的长途商业贸易和文化交流线路的总称。除了上述的路线之外,还包括约于前5世纪形成的草原丝绸之路、中古初年形成,在宋代发挥巨大作用的海上丝绸之路和与西北丝绸之路同时出现,在宋初取代西北丝绸之路成为路上交流通道的南方丝绸之路。

虽然丝绸之路是沿线各君主制国家共同促进经贸发展的产物,但很多人认为,西汉的张骞在前138—前126年和前119年曾两次出使西域,开辟了中外交流的新纪元,并成功将东西方之间最后的珠帘掀开。司马迁在史记中说:“于是西北国始通于汉矣。然张骞凿空,其后使往者皆称博望侯,以为质与国外,外国由此信之”,称赞其开通西域的作用。从此,这条路线被作为“国道”踩了出来,各国使者、商人、传教士等沿着张骞开通的道路,来往络绎不绝。上至王公贵族,下至乞丐狱犯,都在这条路上留下了自己的足迹。这条东西通路,将中原、西域与大伊朗、累范特、阿拉伯紧密联系在一起。经过几个世纪的不断努力,丝绸之路向西伸展到了地中海。广义上丝路的东段已经到达了朝鲜、日本,西段至法国、荷兰。通过海路还可达意大利、埃及,成为亚洲和欧洲、非洲各国经济文化交流的友谊之路。

丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路(英语:The Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road[1]),简称一带一路(英语:The Belt and Road Initiative,缩写B&R)[1],是中华人民共和国政府于2013年倡议[2]并主导的跨国经济带[3]。

一带一路范围涵盖历史上丝绸之路和海上丝绸之路行经的中国、中亚、北亚和西亚、印度洋沿岸、地中海沿岸的国家和地区。中国政府指出,“一带一路”倡议坚持共商、共建、共享的原则,努力实现沿线区域基础设施更加完善,更加安全高效,以形成更高水平的陆海空交流网络。同时使投资贸易的便利化水平更有效的提升,建立高品质、高标准的自由贸易区域网。以使沿线各国经济联系更加紧密,政治互信更加的深入,人文交流更加的广泛[4]。

Als Seidenstraße (chinesisch 絲綢之路 / 丝绸之路, Pinyin Sīchóu zhī Lù ‚die Route / Straße der Seide‘; mongolisch ᠲᠣᠷᠭᠠᠨ ᠵᠠᠮ Tôrgan Jam; kurz: 絲路 / 丝路, Sīlù) bezeichnet man ein altes Netz von Karawanenstraßen, dessen Hauptroute den Mittelmeerraum auf dem Landweg über Zentralasien mit Ostasien verband. Die Bezeichnung geht auf den im 19. Jahrhundert lebenden deutschen Geografen Ferdinand von Richthofen zurück, der den Begriff 1877 erstmals verwendet hat.

Auf der antiken Seidenstraße wurde in westliche Richtung hauptsächlich Seide, gen Osten vor allem Wolle, Gold und Silber gehandelt.[1] Nicht nur Kaufleute, Gelehrte und Armeen nutzten ihr Netz, sondern auch Ideen, Religionen und ganze Kulturkreise diffundierten und migrierten auf den Routen von Ost nach West und umgekehrt: hierüber kamen z. B. der Nestorianismus (aus dem spätantiken Römischen Reich) und der Buddhismus (von Indien) nach China.[1]

Die 6.400 Kilometer[1] lange Route begann in Xi’an und folgte dem Verlauf der Chinesischen Mauer in Richtung Nordwesten, passierte die Taklamakan-Wüste, überwand das Pamirgebirge und führte über Afghanistan in die Levante; von hier wurden die Handelsgüter dann über das Mittelmeer verschifft. Nur wenige Kaufleute reisten auf der gesamten Route, die Waren wurden eher gestaffelt über Zwischenhändler transportiert.

Ihre größte Bedeutung erreichte das Handels- und Wegenetz zwischen 115 v. Chr. und dem 13. Jahrhundert n. Chr. Mit dem allmählichen Verlust römischen Territoriums in Asien und dem Aufstieg Arabiens in der Levante wurde die Seidenstraße zunehmend unsicher und kaum noch bereist. Im 13. und 14. Jahrhundert wurde die Strecke unter den Mongolen wiederbelebt, u. a. benutzte sie zu der Zeit der Venezianer Marco Polo um nach Cathay (China) zu reisen. Nach weit verbreiteter Ansicht war die Route einer der Hauptwege, über die Mitte des 14. Jahrhunderts Pestbakterien von Asien nach Europa gelangten und dort den Schwarzen Tod verursachten.[1]

Teile der Seidenstraße sind zwischen Pakistan und dem autonomen Gebiet Xinjiang in China heute noch als asphaltierte Fernstraße vorhanden (-> Karakorum Highway). Die alte Straße inspirierte die Vereinten Nationen zu einem Plan für eine transasiatische Fernstraße. Von der UN-Wirtschafts- und Sozialkommission für Asien und den Pazifik (UNESCAP) wird die Einrichtung einer durchgehenden Eisenbahnverbindung entlang der Route vorangetrieben, der Trans-Asian Railway.[1]

Die "Neue Seidenstraße", das "One Belt, One Road"-Projekt der Volksrepublik China unter ihrem Staatspräsident Xi Jinping umfasst landgestützte (Silk Road Economic Belt) und maritime (Maritime Silk Road) Infrastruktur- und Handelsrouten, Wirtschaftskorridore und Transportlinien von China über Zentralasien und Russland bzw. über Afrika nach Europa, dazu werden verschiedenste Einrichtungen (z. B. Tiefsee- oder Containerterminals) und Verbindungen (wie Bahnlinien oder Gaspipelines) entwickelt bzw. ausgebaut. Bestehende Korridore sind einerseits Landverbindungen über die Türkei oder Russland und andererseits Anknüpfungen zum Hafen von Shanghai, über Hongkong und Singapur nach Indien und Ostafrika, Dubai, den Suez-Kanal, den griechischen Hafen Piräus nach Venedig.[2]

Das Projekt One Belt, One Road (OBOR, chinesisch 一帶一路 / 一带一路, Pinyin Yídài Yílù ‚Ein Band, Eine Straße‘, neuerdings Belt and Road, da „One“ zu negativ besetzt war) bündelt seit 2013 die Interessen und Ziele der Volksrepublik China unter Staatspräsident Xi Jinping zum Auf- und Ausbau interkontinentaler Handels- und Infrastruktur-Netze zwischen der Volksrepublik und zusammen 64 weiteren Ländern Afrikas, Asiens und Europas. Die Initiative bzw. das Gesamtprojekt betrifft u. A. rund 62 % der Weltbevölkerung und ca. 35 % der Weltwirtschaft.[1][2]

Umgangssprachlich wird das Vorhaben auch „Belt and Road Initiative“ (B&R, BRI) bzw. ebenso wie das Projekt Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia (TRACECA) auch „Neue Seidenstraße“ (新絲綢之路 / 新丝绸之路, Xīn Sīchóuzhīlù) genannt. Es bezieht sich auf den geografischen Raum des historischen, bereits in der Antike genutzten internationalen Handelskorridors „Seidenstraße“; zusammengefasst handelt es sich um zwei Bereiche, einen nördlich gelegenen zu Land mit sechs Bereichen unter dem Titel Silk Road Economic Belt und einen südlich gelegenen Seeweg namens Maritime Silk Road.

シルクロード(絹の道、英語: Silk Road, ドイツ語: Seidenstraße, 繁体字:絲綢之路, 簡体字:丝绸之路)は、中国と地中海世界の間の歴史的な交易路を指す呼称である。絹が中国側の最も重要な交易品であったことから名付けられた。その一部は2014年に初めて「シルクロード:長安-天山回廊の交易路網」としてユネスコの世界遺産に登録された。

「シルクロード」という名称は、19世紀にドイツの地理学者リヒトホーフェンが、その著書『China(支那)』(1巻、1877年)においてザイデンシュトラーセン(ドイツ語:Seidenstraßen;「絹の道」の複数形)として使用したのが最初であるが、リヒトホーフェンは古来中国で「西域」と呼ばれていた東トルキスタン(現在の中国新疆ウイグル自治区)を東西に横断する交易路、いわゆる「オアシスの道(オアシスロード)」を経由するルートを指してシルクロードと呼んだのである。リヒトホーフェンの弟子で、1900年に楼蘭の遺跡を発見したスウェーデンの地理学者ヘディンが、自らの中央アジア旅行記の書名の一つとして用い、これが1938年に『The Silk Road』の題名で英訳されて広く知られるようになった。

シルクロードの中国側起点は長安(陝西省西安市)、欧州側起点はシリアのアンティオキアとする説があるが、中国側は洛陽、欧州側はローマと見る説などもある。日本がシルクロードの東端だったとするような考え方もあり、特定の国家や組織が経営していたわけではないのであるから、そもそもどこが起点などと明確に定められる性質のものではない。

現在の日本でこの言葉が使われるときは、特にローマ帝国と秦・漢帝国、あるいは大唐帝国の時代の東西交易が念頭に置かれることが多いが、広くは近代(大航海時代)以前のユーラシア世界の全域にわたって行われた国際交易を指し、南北の交易路や海上の交易路をも含める。つまり、北方の「草原の道(ステップロード)」から南方の「海の道(シーロード)」までを含めて「シルクロード」と呼ばれるようになっているわけである。

シルクロード経済ベルトと21世紀海洋シルクロード(シルクロードけいざいベルトと21せいきかいようシルクロード、拼音: Sīchóu zhī lù jīngjìdài hé èrshíyī shìjì hǎishàng sīchóu zhī lù、英語: The Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road)とは、2014年11月10日に中華人民共和国北京市で開催されたアジア太平洋経済協力首脳会議で、習近平総書記が提唱した経済圏構想である。

略称は一帯一路(いったいいちろ、拼音: Yídài yílù、英語: The Belt and Road Initiative, BRI; One Belt, One Road Initiative, OBOR)。

The Silk Road was an ancient network of trade routes that connected the East and West. It was central to cultural interaction between the regions for many centuries.[1][2][3] The Silk Road refers to both the terrestrial and the maritime routes connecting East Asia and Southeast Asia with East Africa, West Asia and Southern Europe.

The Silk Road derives its name from the lucrative trade in silk carried out along its length, beginning in the Han dynasty (207 BCE–220 CE). The Han dynasty expanded the Central Asian section of the trade routes around 114 BCE through the missions and explorations of the Chinese imperial envoy Zhang Qian.[4] The Chinese took great interest in the safety of their trade products and extended the Great Wall of China to ensure the protection of the trade route.[5]

Trade on the Road played a significant role in the development of the civilizations of China, Korea,[6] Japan,[2] India, Iran, Afghanistan, Europe, the Horn of Africa and Arabia, opening long-distance political and economic relations between the civilizations.[7] Though silk was the major trade item exported from China, many other goods were traded, as well as religions, syncretic philosophies, sciences, and technologies. Diseases, most notably plague, also spread along the Silk Road.[8] In addition to economic trade, the Silk Road was a route for cultural trade among the civilizations along its network.[9]

Traders in ancient history included the Bactrians, Sogdians, Syrians, Jews, Arabs, Iranians, Turkmens, Chinese, Malays, Indians, Somalis, Greeks, Romans, Georgians, Armenians, and Azerbaijanis.[10]

In June 2014, UNESCO designated the Chang'an-Tianshan corridor of the Silk Road as a World Heritage Site. The Indian portion is on the tentative site list.

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) or the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road is a development strategy adopted by the Chinese government. The 'belt' refers to the overland interconnecting infrastructure corridors; the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) component. The 'road' refers to the sea route corridors; the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR) component.[2] The initiative focuses on connectivity and cooperation between Eurasian countries, primarily the People's Republic of China (PRC).

Until 2016 the initiative was known in English as the One Belt and One Road Initiative (OBOR) but the Chinese came to consider the emphasis on the word "one" as misleading.[3]

The Chinese government calls the initiative "a bid to enhance regional connectivity and embrace a brighter future".[4] Independent observers, however, see it as a push for Chinese dominance in global affairs with a China-centered trading network.[5][6]

La route de la soie est un réseau ancien de routes commerciales entre l'Asie et l'Europe, reliant la ville de Chang'an (actuelle Xi'an) en Chine à la ville d'Antioche, en Syrie médiévale (aujourd'hui en Turquie). Elle tire son nom de la plus précieuse marchandise qui y transitait : la soie.

La route de la soie était un faisceau de pistes par lesquelles transitaient de nombreuses marchandises, et qui monopolisa les échanges Est-Ouest pendant des siècles. Les plus anciennes traces connues de la route de la soie, comme voie de communication avec les populations de l'Ouest, remontent à « 2000 avant notre ère au moins ». Les Chinois en fixent l'ouverture au voyage de Zhang Qian en 138-1261. Mais la route de la soie s'est développée surtout sous la dynastie Han (221 av. J.-C. - 220 ap. J.-C.), en particulier Han Wudi.

Puis sous la dynastie Tang (618-907). À partir du XVe siècle, la route de la soie est progressivement abandonnée, l'instabilité des guerres turco-byzantines, puis la chute de Constantinople poussent en effet les Occidentaux à chercher une nouvelle route maritime vers les Indes. L'abandon de la route de la soie correspond ainsi au début de la période des « Grandes découvertes » durant laquelle les techniques de transport maritime deviennent de plus en plus performantes. Du côté chinois, les empereurs Ming Yongle, puis Ming Xuanzong chargent, à la même époque, l'amiral Zheng He d'expéditions maritimes similaires.

La nouvelle route de la soie ou la Ceinture et la Route2 (stratégie aussi appelée OBOR en anglais pour One Belt, One Road3) est à la fois un ensemble de liaisons maritimes et de voies ferroviaires entre la Chine et l'Europe passant par le Kazakhstan, la Russie, la Biélorussie, la Pologne, l'Allemagne, la France et le Royaume-Uni.

Le nouveau nom est Initiative route et ceinture (Belt and Road Initiative, B&R selon l’acronyme anglais) afin de marquer le fait que ce projet ne se limite pas à une seule route4.

Outre l'amélioration de la connectivité ferroviaire, il s'agit aussi d'une stratégie de développement pour promouvoir la coopération entre les pays sur une vaste bande s'étendant à travers l'Eurasie et pour renforcer la position de la Chine sur le plan mondial, par exemple en préservant la connexion de la Chine avec le reste du monde en cas de tensions militaires sur ses zones côtières5.

La Nouvelle route de la soie a été dévoilée à l'automne 2013 par le gouvernement chinois en tant que pendant terrestre du collier de perles6 ; elle est l'une des priorités de la diplomatie chinoise, sous la présidence de Xi Jinping7.

Selon CNN, ce projet englobera 68 pays représentant 4,4 milliards d’habitants et 62 % du PIB mondial8.

Per via della seta (in cinese: 絲綢之路T, 丝绸之路S, sī chóu zhī lùP; persiano: راه ابریشم, Râh-e Abrisham) s'intende il reticolo, che si sviluppava per circa 8.000 km, costituito da itinerari terrestri, marittimi e fluviali lungo i quali nell'antichità si erano snodati i commerci tra l'impero cinese e quello romano.

Le vie carovaniere attraversavano l'Asia centrale e il Medio Oriente, collegando Chang'an (oggi Xi'an), in Cina, all'Asia Minore e al Mediterraneo attraverso il Medio Oriente e il Vicino Oriente. Le diramazioni si estendevano poi a est alla Corea e al Giappone e, a Sud, all'India. Il nome apparve per la prima volta nel 1877, quando il geografo tedesco Ferdinand von Richthofen (1833-1905) pubblicò l'opera Tagebucher aus China. Nell'Introduzione von Richthofen nomina la Seidenstraße, la «via della seta».

La destinazione finale della seta che su di essa viaggiava (non certo da sola ma insieme a tante altre merci preziose) era Roma, dove per altro non si sapeva con precisione quale ne fosse l'origine (se animale o vegetale) e da dove provenisse. Altre merci altrettanto preziose viaggiavano in senso inverso, e insieme alle merci viaggiavano grandi idee e religioni (concetti fondamentali di matematica, geometria, astronomia) in entrambi i sensi, manicheismo, e nestorianesimo verso oriente. Sulla via della seta compì un complesso giro quasi in tondo anche il buddhismo, dall'India all'Asia Centrale alla Cina e infine al Tibet (il tutto per trovare itinerari che permettessero di evitare le quasi invalicabili montagne dell'Himalaya).

Questi scambi commerciali e culturali furono determinanti per lo sviluppo e il fiorire delle antiche civiltà dell'Egitto, della Cina, dell'India e di Roma, ma furono di grande importanza anche nel gettare le basi del mondo medievale e moderno.

La Nuova via della seta è un'iniziativa strategica della Cina per il miglioramento dei collegamenti e della cooperazione tra paesi nell'Eurasia. Comprende le direttrici terrestri della "zona economica della via della seta" e la "via della seta marittima del XXI secolo" (in cinese: 丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路S, Sīchóu zhī lù jīngjìdài hé èrshíyī shìjì hǎishàng sīchóu zhī lùP), ed è conosciuta anche come "iniziativa della zona e della via" (一带一路S, tradotta comunemente in inglese con Belt and Road Initiative, BRI) o "una cintura, una via" e col corrispondente iniziale acronimo inglese OBOR (One belt, one road), poi modificato in BRI per sottolineare l'estensione del progetto non esclusivo solo della Cina[1], nonostante la prospettiva sinocentrica, com'è stato illustrato in un recente studio italiano[2].

Partendo dallo sviluppo delle infrastrutture di trasporto e logistica, la strategia mira a promuovere il ruolo della Cina nelle relazioni globali, favorendo i flussi di investimenti internazionali e gli sbocchi commerciali per le produzioni cinesi. L'iniziativa di un piano organico per i collegamenti terrestri (la cintura) è stata annunciata pubblicamente dal presidente cinese Xi Jinping a settembre del 2013, e la via marittima ad ottobre dello stesso anno, contestualmente alla proposta di costituire la Banca asiatica d'investimento per le infrastrutture (AIIB), dotata di un capitale di 100 miliardi di dollari USA, di cui la Cina stessa sarebbe il principale socio, con un impegno pari a 29,8 miliardi e gli altri paesi asiatici (tra cui l'India e la Russia) e dell'Oceania avrebbero altri 45 miliardi (l'Italia si è impegnata a sottoscrivere una quota di 2,5 miliardi).

La Ruta de la Seda fue una red de rutas comerciales organizadas a partir del negocio de la seda china desde el siglo I a. C., que se extendía por todo el continente asiático, conectando a China con Mongolia, el subcontinente indio, Persia, Arabia, Siria, Turquía, Europa y África. Sus diversas rutas comenzaban en la ciudad de Chang'an (actualmente Xi'an) en China, pasando entre otras por Karakórum (Mongolia), el Paso de Khunjerab (China/Pakistán), Susa (Persia), el Valle de Fergana (Tayikistán), Samarcanda (Uzbekistán), Taxila (Pakistán), Antioquía en Siria, Alejandría (Egipto), Kazán (Rusia) y Constantinopla (actualmente Estambul, Turquía) a las puertas de Europa, llegando hasta los reinos hispánicos en el siglo XV, en los confines de Europa y a Somalia y Etiopía en el África oriental.

El término "Ruta de la Seda" fue creado por el geógrafo alemán Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen, quien lo introdujo en su obra Viejas y nuevas aproximaciones a la Ruta de la Seda, en 1877. Debe su nombre a la mercancía más prestigiosa que circulaba por ella, la seda, cuya elaboración era un secreto que solo los chinos conocían. Los romanos (especialmente las mujeres de la aristocracia) se convirtieron en grandes aficionados de este tejido, tras conocerlo antes del comienzo de nuestra era a través de los partos, quienes se dedicaban a su comercio. Muchos productos transitaban estas rutas: piedras y metales preciosos (diamantes de Golconda, rubíes de Birmania, jade de China, perlas del golfo Pérsico), telas de lana o de lino, ámbar, marfil, laca, especias, porcelana, vidrio, materiales manufacturados, coral, etc.

En junio de 2014, la Unesco eligió un tramo de la Ruta de la Seda como Patrimonio de la Humanidad con la denominación Rutas de la Seda: red viaria de la ruta del corredor Chang’an-Tian-shan. Se trata de un tramo de 5000 kilómetros de la gran red viaria de las Rutas de la Seda que va desde la zona central de China hasta la región de Zhetysu, situada en el Asia Central, incluyendo 33 nuevos sitios en China, Kazajistán y Kirguistán.1

La Iniciativa del Cinturón y Ruta de la Seda o Belt and Road Initiative, abreviada BRIZNA (también One Belt, One Road, abreviado OBOR y también la Nueva Ruta de la Seda) y NRS (Nueva Ruta de la Seda) por las siglas en español, es el nombre con que se conoce el proyecto político-económico del Secretario General del Partido Comunista de China, Xi Jinping, que propuso en septiembre de 2013 en sus respectivos viajes a Rusia, Kazajistán y Bielorrusia. Bajo el pretexto de que "hace más de dos milenios, las personas diligentes y valientes de Eurasia exploraron y abrieron nuevas vías de intercambio comercial y cultural que unían las principales civilizaciones de Asia, Europa y África, colectivamente llamadas ruta de la seda por generaciones posteriores", el proyecto quiere conectar Europa, Asia del Sur-Oriental, Asia Central y el Oriente Medio, mediante el modelo económico, e implícitamente político, chino.12

El proyecto parte de la reconstrucción de la antigua ruta de la seda y la creación de una ruta marítima paralela, de aquí el nombre de "Cinturón y Ruta". El proyecto afecta a 60 países, el 75% de las reservas energéticas conocidas al mundo, el 70% de la población mundial y generaría el 55% del PIB mundial. El gobierno comunista chino tiene previsto invertir unos 1,4 billones de dólares. Se trataría de un cinturón económico, pero, que algunos comentaristas occidentales ya denominamos "Plan Marshall del siglo XXI al estilo chino". Esta afirmación se sostiene por el hecho que el propio Secretario General Xi Jinping asegura que el proyecto tiene cinco pilares: comunicación política, circulación monetaria, entente entre pueblos, conectividad vital y fluidez. Todo ello se ha visto reflejado de acá el inicio de su puesta en marcha a través de las inversiones importantes con planes de ayuda para empresas chinas interesadas en el mercado exterior. China por el contrario se defiende y argumenta que no se trata de ningún plan Marshall visto que las condiciones políticas impuestas entonces con el Plan Marshall no existen en este proyecto. Pero, artículos de prensa van más allá de las simples afirmaciones de Plan Marshall a la china y hablan directamente de "nuevo orden mundial chino", atrás quedaría la orden mundial norteamericano.3

Nicola Casarini, director de Investigación para Asia del Instituto Affari Internacionali de Roma, sostiene que se trata de una iniciativa ambiciosa que pretende dar cabida en exceso de capacidad interna y a la voluntad de reestructuración de diferentes sectores estratégicos del país, como la industria pesando. La ruta, sin embargo, ha reactivado, a pesar de pretender ser un medio de pacificación de Oriente Medio, las antiguas tensiones del siglo XIX. A la India y Japón, se añade ahora Rusia y los EE.UU. El presidente proyecta la Belt and Road Initiative por unos treinta años. Así el proyecto tendría que estar terminado para el 2049, año donde el país rememoraría los 100 años de fundación de la República Popular.

Вели́кий шёлковый путь — караванная дорога, связывавшая Восточную Азию со Средиземноморьем в древности и в Средние века. В первую очередь использовался для вывоза шёлка из Китая, с чем и связано его название. Путь был проложен во II веке до н. э., вёл из Сианя через Ланьчжоу в Дуньхуан, где раздваивался: северная дорога проходила через Турфан, далее пересекала Памир и шла в Фергану и казахские степи, южная — мимо озера Лоб-Нор по южной окраине пустыни Такла-Макан через Яркенд и Памир (в южной части) вела в Бактрию, а оттуда — в Парфию, Индию и на Ближний Восток вплоть до Средиземного моря. Термин введён немецким географом Фердинандом фон Рихтгофеном в 1877 году.

«Оди́н по́яс и один путь» (кит. 一带一路) — выдвинутое в 2010-х годах Китайской Народной Республикой (КНР) предложение объединённых проектов «Экономического пояса Шёлкового пути» и «Морского Шёлкового пути XXI века».

Предложение было впервые выдвинуто председателем КНР Си Цзиньпином во время визитов в Казахстан и в Индонезию осенью 2013 года[1]. В таких политических документах, как «План социально-экономического развития на 2015 год» и «Доклад о работе правительства», строительство «Одного пояса и одного пути» было включено в список важных задач, поставленных перед новым правительством Китая. Министр иностранных дел Китая Ван И подчеркнул, что осуществление этой инициативы станет «фокусом» внешнеполитической деятельности КНР в 2015 году. Подтверждено, что этот огромный проект будет включён и в план «13-й пятилетки», который будет принят в 2016 году[2]. Суть данной китайской инициативы заключается в поиске, формировании и продвижении новой модели международного сотрудничества и развития с помощью укрепления действующих региональных двусторонних и многосторонних механизмов и структур взаимодействий с участием Китая. На основе продолжения и развития духа древнего Шёлкового пути «Один пояс и один путь» призывает к выработке новых механизмов регионального экономического партнерства, стимулированию экономического процветания вовлечённых стран, укреплению культурных обменов и связей во всех областях между разными цивилизациями, а также содействию мира и устойчивого развития[3]. По официальным данным Китая, «Один пояс и один путь» охватывает большую часть Евразии, соединяя развивающиеся страны, в том числе «новые экономики», и развитые страны. На территории мегапроекта сосредоточены богатые запасы ресурсов, проживает 63 % населения планеты, а предположительный экономический масштаб — 21 трлн долларов США[4].

Transport and traffic

Transport and traffic

Geography

Geography

Military, defense and equipment

Military, defense and equipment

Automobile

Automobile

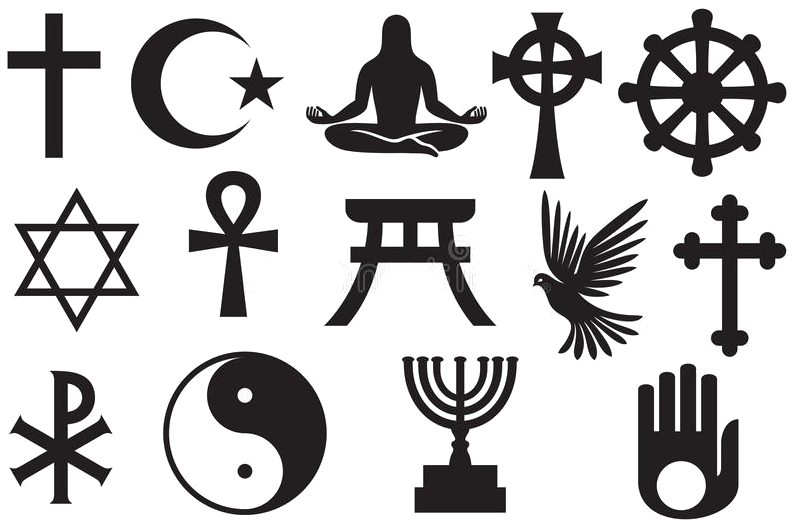

Religion

Religion

History

History