漢德百科全書 | 汉德百科全书

英国

英国

*田径

*田径

男子4x100米接力

男子4x100米接力

*田径

*田径

男子4x400米接力

男子4x400米接力

原子弹

原子弹

英联邦国家

英联邦国家

财政金融

财政金融

财政金融

财政金融

***对冲基金

***对冲基金

地理

地理

地理

地理

***IMF发达国家

***IMF发达国家

对冲基金

对冲基金

对冲基金

对冲基金

英国

英国

IMF发达国家

IMF发达国家

IMF发达国家

IMF发达国家

第二级

第二级

世界田径锦标赛

世界田径锦标赛

2017 London

2017 London

世界田径锦标赛

世界田径锦标赛

1997 Athens

1997 Athens

世界田径锦标赛

世界田径锦标赛

1991 Tokyo

1991 Tokyo

军事、国防和装备

军事、国防和装备

核武器

核武器

军事、国防和装备

军事、国防和装备

§*不扩散核武器条约

§*不扩散核武器条约

北约会员国

北约会员国

政党和政府组织

政党和政府组织

二十个主要工业化国家和新兴国家集团

二十个主要工业化国家和新兴国家集团

政党和政府组织

政党和政府组织

七国集团

七国集团

欧洲国家

欧洲国家

联合国

联合国

联合国安全理事会常任理事国

联合国安全理事会常任理事国

氢弹

氢弹

科学技术

科学技术

科学技术

科学技术

第一次工业革命和它的领跑者与跟跑者

第一次工业革命和它的领跑者与跟跑者

Das Vereinigte Königreich von Großbritannien und Nordirland (englisch ), kurz Vereinigtes Königreich (englisch [juːˌnaɪ̯.tʰɪd ˈkʰɪŋ.dəm], internationale Abkürzung: UK oder GB), ist ein auf den Britischen Inseln vor der Nordwestküste Kontinentaleuropas gelegener europäischer Staat und bildet den größten Inselstaat Europas.

Das Vereinigte Königreich ist eine Union aus den vier Landesteilen England, Wales, Schottland und Nordirland. Im täglichen Sprachgebrauch wird es auch schlicht als Großbritannien oder England bezeichnet. Jedoch stellt England in der eigentlichen Bedeutung nur den größten Landesteil dar, während Großbritannien die Hauptinsel der Britischen Inseln mit den Landesteilen England, Schottland und Wales bezeichnet.

Mit rund 66,4 Millionen Einwohnern[6] steht das Vereinigte Königreich unter den bevölkerungsreichsten Staaten Europas nach Russland und Deutschland an dritter Stelle. Es ist Gründungsmitglied der NATO sowie der Vereinten Nationen. Es ist Atommacht, ständiges Mitglied des UN-Sicherheitsrates und einer der G7-Staaten. Von 1973 bis 2020 war es Mitglied der EWG bzw. später der Europäischen Union.

大不列颠及北爱尔兰联合王国(英语:United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland),国际间的标准简称为联合王国(英语:United Kingdom,缩写作UK)或者不列颠(英语:Britain),汉字文化圈通称“英国”[注 5][9][10](中文早期亦称“英联王国”[注 6]),是本土位于西欧并具有海外领地[注 7]的主权国家。英国位于欧洲大陆西北面,由大不列颠岛、爱尔兰岛东北部分及一系列较小岛屿组成[11]。英国和另一国家唯一的陆上国境线位于北爱尔兰,和爱尔兰共和国相邻[注 8]。英国由大西洋所环绕,东为北海,南为英吉利海峡,西南偏南为凯尔特海,与爱尔兰隔爱尔兰海相望。该国总面积达243,610平方千米(94,060平方英里),为世界面积第80大的主权国家及欧洲面积第11大的主权国家,人口约6636万,为全球第21名及欧洲第3名。

英国为君主立宪制国家,采用议会制进行管辖[12][13]。其首都伦敦为全球城市A++级别城市和国际金融中心,大都会区人口达1380万,为欧洲第三大[14]。现任英国君主为女王伊丽莎白二世,1952年2月6日即位。英国由四个构成国组成,分别为英格兰、苏格兰、威尔士和北爱尔兰[15],其中后三者在权力下放体系之下,各自拥有一定的权力[16][17][18]。三地首府分别为爱丁堡、加的夫和贝尔法斯特。附近的马恩岛、根西行政区及泽西行政区并非联合王国的一部分,而为皇家属地,英国政府负责其国防及外交事务[19]。

英国的构成国之间的关系在历史上经历了一系列的发展。英格兰王国通过1535年和1542年的联合法令将威尔士纳入领土。1707年联合法令使英格兰王国和苏格兰王国共组大不列颠王国,1801年大不列颠王国和爱尔兰王国共组大不列颠及爱尔兰联合王国。1922年爱尔兰中南部26个郡(面积占整个爱尔兰的约六分之五)脱离英国组成爱尔兰自由邦(当今爱尔兰的前身),最终造就了当今的大不列颠及北爱尔兰联合王国[注 9]。大不列颠及北爱尔兰联合王国亦有14块海外领地[20],为往日帝国的遗留部分。大英帝国在1921年达到其巅峰,拥有全球22%的领土,是有史以来面积最大的帝国。英国在语言、文化和法律体系上对其前殖民地保留了一定的影响,因而吸引许多以前英联邦的移民前来居住。

英国为发达国家,以名义GDP为量度是世界第五大经济体,以购买力平价为量度是世界第九大经济体。英国是世界首个工业化国家,工业革命使英国人的生产力大大提高,商业与财富极大的增长,更凭借著工业时代的船坚炮利,1763年—1945年英国为世界第一强国,其鼎盛时期的19世纪还被称作英国的世纪[21][22],当今英国仍是世界强国之一,在经济、文化、军事、科技、教育和政治上均有全球性的显著影响力[23][24]。英国为国际公认的有核国家,其军事开支位列全球第五[25][26]。1945年以来英国即为联合国安全理事会常任理事国。1973年—2020年英国是欧洲联盟(EU)及其前身欧洲经济共同体(EEC)的成员国。英国还是英联邦、欧洲委员会、七国财长峰会、七国集团、二十国集团、北大西洋公约组织、经济合作与发展组织和世界贸易组织成员国。

グレートブリテン及び北アイルランド連合王国(グレートブリテンおよびきたアイルランドれんごうおうこく、英: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland: UK)は、ヨーロッパ大陸の北西岸に位置し、グレートブリテン島・アイルランド島北東部・その他多くの島々から成る立憲君主制国家。首都はロンドン。日本語における通称の一例としてイギリス、英国(えいこく)がある(→#国名)。

イングランド、ウェールズ、スコットランド、北アイルランドという歴史的経緯に基づく4つの「カントリー(国)」が、同君連合型の単一の主権国家を形成している[1]。しかし、政治制度上は単一国家の代表的なモデルであり、連邦国家ではない。

国際連合安全保障理事会常任理事国の一国(五大国)であり、G7・G20に参加する。GDPは世界10位以内に位置する巨大な市場を持ち、ヨーロッパにおける四つの大国「ビッグ4」の一国である。ウィーン体制が成立した1815年以来、世界で最も影響力のある国家を指す列強の一つに数えられる。また、民主主義、立憲君主制など近代国家の基本的な諸制度が発祥した国でもある。

イギリスの擬人化としてはジョン・ブル、ブリタニアが知られる。

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK or U.K.)[14] or Britain,[note 10] is a sovereign country located off the northwestern coast of the European mainland. The United Kingdom includes the island of Great Britain, the northeastern part of the island of Ireland, and many smaller islands.[15] Northern Ireland shares a land border with the Republic of Ireland. Otherwise, the United Kingdom is surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, with the North Sea to the east, the English Channel to the south and the Celtic Sea to the southwest, giving it the 12th-longest coastline in the world. The Irish Sea separates Great Britain and Ireland. The total area of the United Kingdom is 94,000 square miles (240,000 km2).

The United Kingdom is a unitary parliamentary democracy and constitutional monarchy.[note 11][16][17] The monarch is Queen Elizabeth II, who has reigned since 1952, making her the world's longest-serving current head of state.[18] The United Kingdom's capital is London, a global city and financial centre with an urban area population of 10.3 million.[19]

The United Kingdom consists of four countries: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.[20] Their capitals are London, Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast, respectively. Apart from England, the countries have their own devolved governments,[21] each with varying powers.[22][23] Other major cities include Birmingham, Glasgow, Leeds, Liverpool, and Manchester.

The nearby Isle of Man, Bailiwick of Guernsey and Bailiwick of Jersey are not part of the UK, being Crown dependencies with the British Government responsible for defence and international representation.[24] The medieval conquest and subsequent annexation of Wales by the Kingdom of England, followed by the union between England and Scotland in 1707 to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the union in 1801 of Great Britain with the Kingdom of Ireland created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Five-sixths of Ireland seceded from the UK in 1922, leaving the present formulation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The UK's name was adopted in 1927 to reflect the change.[note 12] There are fourteen British Overseas Territories,[25] the remnants of the British Empire which, at its height in the 1920s, encompassed almost a quarter of the world's landmass and was the largest empire in history. British influence can be observed in the language, culture and political systems of many of its former colonies.[26][27][28][29][30] The United Kingdom has the world's sixth-largest economy by nominal gross domestic product (GDP), and the ninth-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP). It has a high-income economy and a very high human development index rating, ranking 14th in the world. It was the world's first industrialised country and the world's foremost power during the 19th and early 20th centuries.[31][32] The UK remains a great power, with considerable economic, cultural, military, scientific and political influence internationally.[33][34] It is a recognised nuclear weapons state and is sixth in military expenditure in the world.[35] It has been a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council since its first session in 1946.

The United Kingdom is a leading member of the Commonwealth of Nations, the Council of Europe, the G7, the G20, NATO, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Interpol and the World Trade Organization (WTO). It was a member of the European Union (EU) and its predecessor, the European Economic Community (EEC), for 47 years, between 1 January 1973 and withdrawal on 31 January 2020.

Le Royaume-Uni (prononcé en français : /ʁwajom‿yni/a Écouter), en forme longue le Royaume-Uni de Grande-Bretagne et d'Irlande du Nordb (en anglais : United Kingdom /juːˌnaɪtɪd ˈkɪŋdəm/c Écouter et United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland)d, est un pays d'Europe de l'Ouest, ou selon certaines définitions, d'Europe du Nord, dont le territoire comprend l'île de Grande-Bretagne et la partie nord de l'île d'Irlande, ainsi que de nombreuses petites îles autour de l'archipel. Le territoire du Royaume-Uni partage une frontière terrestre avec la république d'Irlande, et est entouré par l'océan Atlantique au nord, la mer du Nord à l'est, la Manche au sud, la mer Celtique au sud-sud-ouest, la mer d'Irlande au sud-ouest et les mers intérieures de la côte ouest de l'Écosse au nord-ouest. Le Royaume-Uni couvre une superficie de 246 690 km2, faisant de lui le 80e plus grand pays du monde, et le 11e d'Europe. Il est le 22e pays plus peuplé du monde, avec une population estimée à 65,1 millions d'habitants. Le Royaume-Uni est une monarchie constitutionnelle7 ; il possède un système parlementaire de gouvernance8,3. Sa capitale est Londres, une ville mondiale et la première place financière au monde.

Le Royaume-Uni est composé de quatre nations constitutives : l'Angleterre, l'Écosse, le pays de Galles et l'Irlande du Nord. Les trois dernières ont des administrations dévolues9, chacune avec des pouvoirs variés10, basés dans leurs capitales régionales, respectivement Édimbourg, Cardiff et Belfast. Les bailliages de Guernesey, de Jersey et l'île de Man sont des dépendances de la Couronne et ne sont donc pas rattachés au pays11. De plus, le pays comprend quatorze territoires d'outre-mer12, disséminés sur plusieurs océans. Le Royaume-Uni est né en 1707, lorsque les royaumes d'Angleterre et d'Écosse s'unifièrent pour former le royaume de Grande-Bretagne, qui s'agrandit en 1801 en s'unifiant avec le royaume d'Irlande pour former le Royaume-Uni de Grande-Bretagne et d'Irlande. En 1922, l'Irlande du Sud fit sécession du Royaume-Uni, donnant naissance à l'État d'Irlande, amenant au nom officiel et actuel de « Royaume-Uni de Grande-Bretagne et d'Irlande du Nord ». Les territoires d'outre-mer, anciennement des colonies, sont les vestiges de l'Empire britannique, qui, jusqu'à la seconde moitié du XXe siècle, était le plus vaste empire colonial de l'histoire.

L'influence britannique peut être observée dans la langue, la culture, le système politique et juridique des anciennes colonies. Le Royaume-Uni est un pays développé. Il est en 2018 la cinquième puissance mondiale par son PIB nominal13 et la neuvième puissance en termes de PIB à parité de pouvoir d'achat. Berceau de la révolution industrielle, le pays fut la première puissance mondiale durant la majeure partie du XIXe siècle14,15. Le Royaume-Uni reste une grande puissance, avec une influence internationale considérable sur le plan économique, politique, culturel, militaire et scientifique16,17. Il est également une puissance nucléaire reconnue avec le sixième budget de la défense le plus élevé18. Le Royaume-Uni est membre du Commonwealth, du Conseil de l'Europe, du G7, du G20, de l'OTAN, de l'OCDE, de l'OMC, et membre permanent du Conseil de sécurité des Nations unies depuis 1946. Le Royaume-Uni a adhéré le 1er janvier 1973 à la CEE, devenue Union Européenne, puis en est sorti le 1er février 2020 à la suite de la victoire du «

大宪章(拉丁语:Magna Carta,英语:The Great Charter)又被称作自由大宪章(拉丁语:Magna Carta Libertatum,英语:The Great Charter of the Liberties),是英格兰国王约翰最初于1215年6月15日在温莎附近的兰尼米德订立的拉丁文政治性授权文件;但在随后的版本中,大部分对英国王室绝对权力的直接挑战条目被删除;1225年首次成为法律;1297年的英文版本至今仍然是英格兰威尔士的有效法律。

这份由坎特伯里大主教史蒂芬·朗顿起草的大宪章乃封建贵族用来对抗英国国王(主要是针对当时的约翰)权力的封建权利保障协议。订立大宪章的主因是教皇、英王约翰及封建贵族对王室权力出现意见分歧。大宪章要求王室放弃部分权力,保护教会的权力,尊重司法过程,接受王权受法律的限制。大宪章是英国在建立宪法政治这长远历史过程的开始。

约翰死后,亨利三世的摄政政府为了争取支持,在删除了一些比较极端的条款后,于1216年重新颁布了“大宪章”。到1217年第一次诸侯战争结束时,亨利三世颁布的大宪章成为了停战协议的一部分。由于资金匮乏,1225年,亨利再次颁布了“大宪章”,以此换取征收新税的权力。亨利三世的儿子爱德华一世在1297年也采取了同样的措施,爱德华一世确认了大宪章是英格兰成文法的一部分。

マグナ・カルタまたは大憲章(だいけんしょう)(羅: Magna Carta、羅: Magna Carta Libertatum、英: the Great Charter of the Liberties、直訳では「自由の大憲章」)は、イングランド王国においてジョン王により制定された憲章である。イングランド国王の権限を制限したことで憲法史の草分けとなった。また世界に先駆け敵性資産の保護を成文化した[1]。

ブーヴィーヌの戦いでフランスに敗北したジョン王は、戦後さらなる徴兵を必要とした。しかし、イングランド貴族たちは度重なる軍役に反発する。彼らは徴兵に応じるどころか、ジョン王に対し、それぞれ抱えていた不満を救済するよう強く求めた。 1215年6月19日、貴族たちの要求をまとめる形でラニーミードにおいて制定されたのがマグナ・カルタである。これにより、イングランドにおいて法の支配が確認されることになった。マグナ・カルタは教皇インノケンティウス3世の勅令により無効とされたものの、その後、数度改正されている(英語版を参照されたい)。 1225年に作られたヘンリー3世のマグナ・カルタの一部は、現在でもイギリスにおいて憲法を構成する法典の一つとして効力を有する。

マグナ・カルタの理念は、国王と議会が対立した17世紀に再度注目されるようになり、エドワード・コーク卿ほか英国の裁判官たちによって憲法原理としてまとめられた。また、清教徒革命やアメリカ独立戦争の根拠ともなった。2009年、マグナ・カルタはユネスコの『世界の記憶』に登録された。

Magna Carta Libertatum (Medieval Latin for "the Great Charter of the Liberties"), commonly called Magna Carta (also Magna Charta; "Great Charter"),[a] is a charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215.[b] First drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury to make peace between the unpopular King and a group of rebel barons, it promised the protection of church rights, protection for the barons from illegal imprisonment, access to swift justice, and limitations on feudal payments to the Crown, to be implemented through a council of 25 barons. Neither side stood behind their commitments, and the charter was annulled by Pope Innocent III, leading to the First Barons' War. After John's death, the regency government of his young son, Henry III, reissued the document in 1216, stripped of some of its more radical content, in an unsuccessful bid to build political support for their cause. At the end of the war in 1217, it formed part of the peace treaty agreed at Lambeth, where the document acquired the name Magna Carta, to distinguish it from the smaller Charter of the Forest which was issued at the same time. Short of funds, Henry reissued the charter again in 1225 in exchange for a grant of new taxes. His son, Edward I, repeated the exercise in 1297, this time confirming it as part of England's statute law.

The charter became part of English political life and was typically renewed by each monarch in turn, although as time went by and the fledgling English Parliament passed new laws, it lost some of its practical significance. At the end of the 16th century there was an upsurge in interest in Magna Carta. Lawyers and historians at the time believed that there was an ancient English constitution, going back to the days of the Anglo-Saxons, that protected individual English freedoms. They argued that the Norman invasion of 1066 had overthrown these rights, and that Magna Carta had been a popular attempt to restore them, making the charter an essential foundation for the contemporary powers of Parliament and legal principles such as habeas corpus. Although this historical account was badly flawed, jurists such as Sir Edward Coke used Magna Carta extensively in the early 17th century, arguing against the divine right of kings propounded by the Stuart monarchs. Both James I and his son Charles I attempted to suppress the discussion of Magna Carta, until the issue was curtailed by the English Civil War of the 1640s and the execution of Charles.

The political myth of Magna Carta and its protection of ancient personal liberties persisted after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 until well into the 19th century. It influenced the early American colonists in the Thirteen Colonies and the formation of the American Constitution in 1787, which became the supreme law of the land in the new republic of the United States.[c] Research by Victorian historians showed that the original 1215 charter had concerned the medieval relationship between the monarch and the barons, rather than the rights of ordinary people, but the charter remained a powerful, iconic document, even after almost all of its content was repealed from the statute books in the 19th and 20th centuries. Magna Carta still forms an important symbol of liberty today, often cited by politicians and campaigners, and is held in great respect by the British and American legal communities, Lord Denning describing it as "the greatest constitutional document of all times – the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot".[4]

In the 21st century, four exemplifications of the original 1215 charter remain in existence, two at the British Library, one at Lincoln Cathedral and one at Salisbury Cathedral. There are also a handful of the subsequent charters in public and private ownership, including copies of the 1297 charter in both the United States and Australia. The original charters were written on parchment sheets using quill pens, in heavily abbreviated medieval Latin, which was the convention for legal documents at that time. Each was sealed with the royal great seal (made of beeswax and resin sealing wax): very few of the seals have survived. Although scholars refer to the 63 numbered "clauses" of Magna Carta, this is a modern system of numbering, introduced by Sir William Blackstone in 1759; the original charter formed a single, long unbroken text. The four original 1215 charters were displayed together at the British Library for one day, 3 February 2015, to mark the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta.

Magna Carta, latin pour Grande Charte, désigne plusieurs versions d'une charte arrachée une première fois par le baronnage anglais au roi Jean sans Terre le 15 juin 1215 après une courte guerre civile qui culmine le 17 mai par la prise de Londres. Les barons, excédés par les demandes militaires et financières du roi et par les échecs répétés en France, en particulier à Bouvines et à La Roche-aux-Moines, y imposent, dans un esprit de retour à l'ordre ancien, leurs exigences, dont la libération d'otages retenus par le roi, le respect de certaines règles de droit propres à la noblesse, la reconnaissance des franchises ecclésiastiques et bourgeoises, le contrôle de la politique fiscale par un Grand Conseil (en).

Elle est abrogée deux mois après son scellement puis réactivée en une version expurgée, sans conseil des barons (en), le 12 novembre 1216 durant la minorité de Henri III, amendée et complétée le 6 novembre 1217 d'une loi domaniale (en) dite Charte de forêt. Une quatrième version, réduite de près de la moitié par rapport à celle de 1215 et très peu différente de la précédente, est officiellement promulguée le 11 février 1225. Confirmée solennellement le 10 novembre 1297, c'est elle que désignera dès lors l'expression Magna Carta. En 1354, y sont introduites, sans rien changer aux statuts sociaux en vigueur, les notions d'égalité universelle devant la loi, principe qui sera argumenté en vain à la fin du XVIIe siècle pour faire libérer les esclaves parvenus sur le territoire anglais1, et de droit à un procès équitable.

Document décalqué de la Charte des libertés initialement sans conséquence réelle mais vigoureusement promu entre 1297 et 1305 sous le règne finissant d'Édouard Ier pour soutenir une féodalité déliquescente, il est régulièrement revendiqué par le Parlement durant tout le bas Moyen Âge mais tombe en désuétude à la suite des bouleversements institutionnels induits par la guerre des Deux-Roses. Sorti de l'oubli, il est instrumentalisé au début du XVIIe siècle par les opposants à une monarchie absolue, tel Henri Spelman (en), et érigé à la suite de la Révolution par les partisans d'une monarchie constitutionnelle comme une preuve d'ancienneté de leurs revendications (en). Ses articles 38 et 39 concernant ce qui sera désigné à partir de 1305 sous l'expression Habeas corpus, de simple rappel d'un privilège aristocratique devient, à l'occasion du vote de la Loi de l'Habeas corpus (en) en 1679, le symbole d'une justice qui proscrit les arrestations arbitraires — partant du principe de son indépendance vis-à-vis de l'exécutif — voire de la liberté individuelle.

La Magna Charta Libertatum (dal latino medievale, "Grande Carta delle libertà"), comunemente chiamata Magna Carta, è una carta accettata il 15 giugno 1215 dal re Giovanni d'Inghilterra (soprannominato anche "Giovanni Senza Terra", perché privo di appannaggi reali) a Runnymede, nei pressi di Windsor. Redatta dall'Arcivescovo di Canterbury per raggiungere la pace tra l'impopolare re e un gruppo di baroni ribelli, garantì la tutela dei diritti della chiesa, la protezione ai baroni dalla detenzione illegale, la garanzia di una rapida giustizia e la limitazione sui pagamenti feudali alla corona.

Fu chiamata magna per non confonderla con un provvedimento minore, una carta emanata proprio in quegli anni per sancire una serie di limiti al potere del sovrano inglese. Pur presentandosi, quindi, come un atto di concessione unilaterale da parte del re, costituiva, in realtà, un contratto di riconoscimento di diritti reciproci. Dopo la morte di Giovanni, il governo di Guglielmo il Maresciallo, reggente per il suo giovane figlio Enrico III, fece emanare nuovamente il documento nel 1216, spogliato di alcuni dei suoi contenuti più radicali, in un tentativo fallito di costruirsi un sostegno politico; l'anno seguente, alla fine della prima guerra dei baroni, fece parte del trattato di pace concordato a Lambeth. A corto di fondi, Enrico fece ripubblicare ancora una volta la Carta nel 1225, in cambio di una concessione di nuove tasse; suo figlio, Edoardo I, lo fece nel 1297, questa volta confermandola come parte della legge statutaria dell'Inghilterra.

Benché la Magna Carta sia stata più volte modificata, nel corso dei secoli, da leggi ordinarie emanate dal parlamento, conserva tuttora lo status di Carta fondamentale della monarchia britannica e rimangono tuttora in vigore gli articoli 1, 9 e 29 dell’ultima versione, quella del 1297.

Giovanni, che aveva firmato questo documento sotto coercizione e combattuto i ribelli con la benedizione del Papa Innocenzo III fino alla morte, fu di fatto l'ultimo vero sovrano teocratico, anche se molti discendenti riuscirono con successo a restaurare la monarchia assoluta.[1]

Magna Carta Libertatum (en latín medieval, «Gran Carta de las Libertades»), más conocida como la Carta Magna (en inglés y latín medieval, Magna Carta, «Gran Carta»),i es una carta otorgada por Juan I de Inglaterra en Runnymede, cerca de Windsor, el 15 de junio de 1215.ii Redactada en primer lugar por el arzobispo de Canterbury, Stephen Langton, para hacer las paces entre el monarca inglés, con amplia impopularidad, y un grupo de barones sublevados, prometía la protección de los derechos eclesiásticos, la protección de los barones ante el encarcelamiento ilegal, el acceso a justicia inmediata y las limitaciones a las tarifas feudales a la Corona, que se implementarían mediante un concilio de veinticinco barones. Ninguno de los bandos cumplió con sus compromisos y la carta fue anulada por el papa Inocencio III, lo que provocó a la primera Guerra de los Barones. Después de la muerte de Juan I, el gobierno de regencia del joven Enrique III volvió a promulgar el documento en 1216 —aunque despojado de algunos de sus incisos más radicales—, en un intento fallido de obtener apoyo político para su causa. Al final de la guerra en 1217, la carta formó parte del tratado de paz acordado en Lambeth, donde adquirió el nombre de «Carta Magna» para distinguirla de la pequeña Carta Forestal emitida al mismo tiempo. Ante la falta de fondos, Enrique III decretó nuevamente la carta en 1225 a cambio de una concesión de nuevos impuestos. Su hijo Eduardo I repitió la sanción en 1297, esta vez confirmándola como parte del derecho estatutario de Inglaterra.

El documento se volvió en parte de la vida política inglesa y era renovada habitualmente por el monarca de turno, aunque con el paso del tiempo el recién creado Parlamento inglés aprobó nuevas leyes, por lo que la carta perdió parte de su significado práctico. A finales del siglo XVI hubo un creciente interés por la Carta Magna. Los abogados e historiadores de la época pensaban que existía una antigua constitución inglesa, remontada a los días de los anglosajones, que protegía las libertades individuales de los ingleses. Argumentaron que la invasión normanda de 1066 había suprimido estos derechos; según ellos, la Carta Magna fue un intento popular de restaurarlos, lo que la convirtió en una base esencial para los poderes contemporáneos del Parlamento y principios legales como el habeas corpus. Aunque este relato histórico tenía sus fallas, juristas como Edward Coke utilizaron mucho la Carta Magna a principios del siglo XVII para objetar el derecho divino de los reyes, propuesto por los Estuardo desde el trono. Tanto Jacobo I como su hijo Carlos I intentaron prohibir la discusión de la Carta Magna, hasta que la Revolución inglesa de los años 1640 y la ejecución de Carlos I restringieron el tema.

El mito político de la Carta Magna y su protección de las antiguas libertades personales persistieron después de la Revolución Gloriosa de 1688 hasta bien entrado el siglo XIX. Influyó en los primeros colonos americanos en las Trece Colonias y en la formación de la Constitución estadounidense en 1787, que se convirtió en la ley suprema de los territorios en la nueva república de los Estados Unidos.iii La investigación de historiadores victorianos demostró que la carta original de 1215 concernía a la relación medieval entre el monarca inglés y los barones, en lugar de los derechos de la gente común, pero dichaa carta seguía siendo un documento poderoso e icónico, incluso después de que casi todo su contenido fue derogado de los estatutos de los siglos XIX y XX. La Carta Magna aún constituye un símbolo importante de la libertad, frecuentemente es citada por políticos y activistas y es respetada por las comunidades legales británicas y estadounidenses; el jurista Tom Denning la describió como «el documento constitucional más grande de todos los tiempos: la fundación del libertad del individuo contra la autoridad arbitraria del déspota».6

En el siglo XXI, solo existen cuatro copias auténticas de la carta de 1215: dos en la Biblioteca Británica, una en la catedral de Lincoln y otra en la catedral de Salisbury. También existe un puñado de cartas posteriores en manos públicas y privadas, como copias de la carta de 1297 conservadas en los Estados Unidos y Australia. Las cartas originales se escribieron en hojas de pergamino utilizando plumas de ave, en latín medieval rigurosamente abreviado, que era la convención de documentos legales en ese tiempo. Cada uno recibió el gran sello real (hecho de cera estampada y lacre de resina), aunque pocos de estos sellos han sobrevivido. Aunque los eruditos se refieren a 63 «cláusulas» numeradas de la Carta Magna, este sistema moderno de numeración fue introducido por William Blackstone en 1759; el estatuto original era un texto único, vasto e ininterrumpido. El conjunto de las cuatro cartas originales de 1215 se exhibió en la Biblioteca Británica durante un día (3 de febrero de 2015) para conmemorar el 800.º aniversario de la Carta Magna.

Вели́кая ха́ртия во́льностей (лат. Magna Carta, также Magna Charta Libertatum) — политико-правовой документ, составленный в июне 1215 года на основе требований английской знати к королю Иоанну Безземельному и защищавший ряд юридических прав и привилегий свободного населения средневековой Англии. Состоит из 63 статей, регулировавших вопросы налогов, сборов и феодальных повинностей, судоустройства и судопроизводства, прав английской церкви, городов и купцов, наследственного права и опеки. Ряд статей Хартии содержал правила, целью которых было ограничение королевской власти путём введения в политическую систему страны особых государственных органов — общего совета королевства и комитета двадцати пяти баронов, обладавшего полномочиями предпринимать действия по принуждению короля к восстановлению нарушенных прав; в силу этого данные статьи получили название конституционных.

Великая хартия вольностей появилась на волне глубокого обострения социально-политических противоречий, причиной которых стали многочисленные случаи злоупотреблений со стороны короны. Непосредственному принятию Хартии предшествовало масштабное противостояние короля и английских баронов, поддержанных всеми свободными сословиями. Несмотря на то, что Иоанн Безземельный, вынужденный утвердить Хартию, вскоре отказался от её исполнения, впоследствии ряд её положений в том или ином виде неоднократно был подтвержден другими английскими монархами. В настоящее время продолжают действовать четыре статьи Хартии, в связи с чем она признается старейшей частью некодифицированной британской конституции.

Изначально Великая хартия вольностей носила консервативный характер: в большинстве статей она закрепляла, упорядочивала и уточняла общепризнанные и устоявшиеся нормы обычного феодального права. Однако, преследуя защиту феодальных интересов, нормы Хартии использовали ряд прогрессивных принципов — соответствия действий должностных лиц закону, соразмерности деяния и наказания, признания виновным только в судебном порядке, неприкосновенности имущества, свободы покинуть страну и возвратиться в неё и других. В период подготовки и проведения Английской революции Хартия приобрела значение символа политической свободы, став знаменем борьбы англичан против королевского деспотизма и фундаментом Петиции о праве и других конституционных документов, а провозглашенные ею гарантии недопущения нарушений прав английских подданных оказали влияние на становление и развитие института прав человека.

Das British Museum (BM, deutsch: Britisches Museum) in London ist eines der größten und bedeutendsten kulturgeschichtlichen Museen der Welt. Das Natural History Museum war einst Teil des British Museum und ist seit 1963 eigenständig. Die British Museum Library war früher die größte Bibliothek des Landes. 1973 bildete sie den Grundstock für die neu gegründete British Library.

Das Museum entstand, als 1753 der Arzt und Wissenschaftler Sir Hans Sloane seine sehr umfangreiche Literatur- und Kunstsammlung dem Staat übereignete. Das Parlament beschloss, diese Sammlung unter dem Namen British Museum zu erhalten und zu pflegen. Das Museum wurde im Montagu House, einem Herrenhaus im ehemaligen Londoner Stadtteil Bloomsbury, eingerichtet, und öffnete seine Pforten am 15. Januar 1759. Bedingt durch die stetig wachsende Sammlung und steigende Besucherzahlen wurde 1824 der Umzug in ein größeres, neu zu errichtendes Gebäude beschlossen. 1850 war der Umzug abgeschlossen, und die Gebäude hatten im Wesentlichen ihre heutige Gestalt. Den wichtigsten Impuls zur modernen Ausweitung der Sammlungsbestände erhielt das Museum mit der Anstellung von Augustus Wollaston Franks, zunächst 1851 als Assistent für die damals neugeschaffene Abteilung für britische und mittelalterliche Geschichte, dann von 1866 bis 1896 als deren Kurator. Für die Museumshistorikerin Marjorie Caygill wurde Franks zum „vermutlich wichtigste[n] Sammler in der Geschichte des Britischen Museums“.[2] Im Laufe der Zeit wurden verschiedene Teile der Sammlung aus Platzgründen in andere Gebäude verlegt.

大英博物馆是世界上历史最悠久、规模最宏伟的综合性博物馆,位于英国伦敦。它收藏了世界各地的许多文物和图书珍品,藏品之丰富、种类之繁多为全世界博物馆所罕见。藏品主要是英国于18世纪至19世纪发起的战争中掠夺得来,主要受害国家包括希腊、埃及及中国等。大英博物馆位于伦敦中心,是一座规模庞大的古罗马柱式建筑,十分壮观。这里珍藏的文物和图书资料在世界上久负盛名。大英博物馆建于1753年,6年后正式开 放,原来主要收藏图书,后来兼收历史文物和各国古代艺术品,其中不少是仅存的珍本。18世纪至19世纪中叶,英帝国向世界扩张,对各国进行文化掠夺,大量 珍贵文物运抵伦敦,数量之多,大英博物馆盛不下,只得分藏于各个博物馆。目前,埃及文物馆是其中最大的陈列馆,有7万多件古埃及各种文物,代表着古埃及的高度文明。希腊和罗马文物馆、东方文物馆的大量文物反映了古希腊罗马、古代中国的灿烂文化。

大英博物馆(英语:British Museum)是一座于英国伦敦的综合博物馆,也是世界上规模最大、最著名的博物馆之一,成立于1753年。目前博物馆拥有藏品800多万件。由于空间的限制,目前还有大批藏品未能公开展出。博物馆在1759年1月15日起正式对公众开放。

大英博物馆的渊源最早可追溯到1753年。汉斯·斯隆(1660至1753年)爵士是当时的一位著名收藏家,1753年他去世后遗留下来的个人藏品达71000件,还有大批植物标本及书籍、手稿。根据他的遗嘱,所有藏品都捐赠给国家。这些藏品最后被交给了英国国会。在通过公众募款筹集建筑博物馆的资金后,大英博物馆最终于1759年1月15日在伦敦市区附近的蒙塔古大楼(Montague Building)成立并对公众开放。[来源请求]

博物馆在开放后通过英国人在各地的各种活动攫取了大批珍贵藏品,早期的大英博物馆倾向于收集自然历史标本,但也有大量文物、书籍,因此吸引了大批参观者。到了19世纪初,蒙塔古大楼已经显得不敷使用了。于是1824年博物馆决定在蒙塔古大楼北面建造一座新馆,并在1840年代完成,旧蒙塔古大楼不久后便被拆除。新馆建成后不久又在院子里建了对公众开放的圆形阅览室。

由于空间的限制,1880年大英博物馆将自然历史标本与考古文物分离,大英博物馆专门收集考古文物。1973年,博物馆再次重新划分,将书籍、手稿等内容分离组成新的大英图书馆。

大中庭(Great Court)位于大英博物馆中心,于2000年12月建成开放,目前是欧洲最大的有顶广场。广场的顶部是用3312块三角形的玻璃片组成的。广场中央为大英博物馆的阅览室,对公众开放。

大英博物馆阅览室原来属于大英图书馆,但图书馆阅览室已经搬到了图书馆大楼,现在为博物馆的阅览室。

大英博物馆目前分为10个研究和专业馆:非洲、大洋洲和美洲馆;古埃及和苏丹馆;亚洲馆;不列颠、欧洲和史前时期馆;硬币和纪念币馆;保护和科学研究馆;希腊和罗马馆;中东馆;便携古物和珍宝馆;版画和素描馆。

大英博物館(だいえいはくぶつかん、英: British Museum)は、イギリス・ロンドンにある博物館である。

世界最大の博物館の一つで、古今東西の美術品や書籍や略奪品など約800万点が収蔵されている(うち常設展示されているのは約15万点)。収蔵品は美術品や書籍のほかに、考古学的な遺物・標本・硬貨やオルゴールなどの工芸品、世界各地の民族誌資料など多岐に渡る。イギリス自身のものも所蔵・展示されている。余りに多岐にわたることから、常設展示だけでも一日で全てを見ることはほぼ不可能である[3]。

世界中の博物館との連携による巡回展計画や途上国の博物館への技術協力なども進められている。教育計画も充実しており、学校との連携した教育計画、家族向け教育計画、成人向け教育計画、障害者や移民・亡命希望者など社会的弱者のための教育計画などがある。また、「アジア美術修了証書」という大学院修士課程水準の教育過程も博物館教育計画の一環として提供されている。

来館者の約56%が外国人観光客といわれている。このため各国語版の案内書も充実しており、入り口脇や屋根中庭(グレート・コート)にある販売店では公式案内書が販売されているが、この中には日本語版 (£6) も見られる。

The British Museum, in the Bloomsbury area of London, United Kingdom, is a public institution dedicated to human history, art and culture. Its permanent collection of some eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence,[3] having been widely sourced during the era of the British Empire. It documents the story of human culture from its beginnings to the present.[a] It was the first public national museum in the world.[4]

The British Museum was established in 1753, largely based on the collections of the Irish physician and scientist Sir Hans Sloane.[5] It first opened to the public in 1759, in Montagu House, on the site of the current building. Its expansion over the following 250 years was largely a result of expanding British colonisation and has resulted in the creation of several branch institutions, the first being the Natural History Museum in 1881.

In 1973, the British Library Act 1972 detached the library department from the British Museum, but it continued to host the now separated British Library in the same Reading Room and building as the museum until 1997. The museum is a non-departmental public body sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, and as with all national museums in the UK it charges no admission fee, except for loan exhibitions.[6]

Its ownership of some of its most famous objects originating in other countries is disputed and remains the subject of international controversy, most notably in the case of the Parthenon Marbles.[7]

Sir Hans Sloane

Although today principally a museum of cultural art objects and antiquities, the British Museum was founded as a "universal museum". Its foundations lie in the will of the Irish physician and naturalist Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), a London-based doctor and scientist from Ulster. During the course of his lifetime, and particularly after he married the widow of a wealthy Jamaican planter[8], Sloane gathered a large collection of curiosities and, not wishing to see his collection broken up after death, he bequeathed it to King George II, for the nation, for a sum of £20,000.[9]

At that time, Sloane's collection consisted of around 71,000 objects of all kinds[10] including some 40,000 printed books, 7,000 manuscripts, extensive natural history specimens including 337 volumes of dried plants, prints and drawings including those by Albrecht Dürer and antiquities from Sudan, Egypt, Greece, Rome, the Ancient Near and Far East and the Americas.[11]

Foundation (1753)

On 7 June 1753, King George II gave his Royal Assent to the Act of Parliament which established the British Museum.[b] The British Museum Act 1753 also added two other libraries to the Sloane collection, namely the Cottonian Library, assembled by Sir Robert Cotton, dating back to Elizabethan times, and the Harleian Library, the collection of the Earls of Oxford. They were joined in 1757 by the "Old Royal Library", now the Royal manuscripts, assembled by various British monarchs. Together these four "foundation collections" included many of the most treasured books now in the British Library[13] including the Lindisfarne Gospels and the sole surviving manuscript of Beowulf.[c]

The British Museum was the first of a new kind of museum – national, belonging to neither church nor king, freely open to the public and aiming to collect everything. Sloane's collection, while including a vast miscellany of objects, tended to reflect his scientific interests.[14] The addition of the Cotton and Harley manuscripts introduced a literary and antiquarian element and meant that the British Museum now became both National Museum and library.[15]

Cabinet of curiosities (1753–1778)

The body of trustees decided on a converted 17th-century mansion, Montagu House, as a location for the museum, which it bought from the Montagu family for £20,000. The trustees rejected Buckingham House, on the site now occupied by Buckingham Palace, on the grounds of cost and the unsuitability of its location.[16][d]

With the acquisition of Montagu House, the first exhibition galleries and reading room for scholars opened on 15 January 1759.[17] At this time, the largest parts of collection were the library, which took up the majority of the rooms on the ground floor of Montagu House and the natural history objects, which took up an entire wing on the second state storey of the building. In 1763, the trustees of the British Museum, under the influence of Peter Collinson and William Watson, employed the former student of Carl Linnaeus, Daniel Solander to reclassify the natural history collection according to the Linnaean system, thereby making the Museum a public centre of learning accessible to the full range of European natural historians.[18] In 1823, King George IV[19] gave the King's Library assembled by George III, and Parliament gave the right to a copy of every book published in the country, thereby ensuring that the museum's library would expand indefinitely. During the few years after its foundation the British Museum received several further gifts, including the Thomason Collection of Civil War Tracts and David Garrick's library of 1,000 printed plays. The predominance of natural history, books and manuscripts began to lessen when in 1772 the museum acquired for £8,410 its first significant antiquities in Sir William Hamilton's "first" collection of Greek vases.[20]

Indolence and energy (1778–1800)

From 1778, a display of objects from the South Seas brought back from the round-the-world voyages of Captain James Cook and the travels of other explorers fascinated visitors with a glimpse of previously unknown lands. The bequest of a collection of books, engraved gems, coins, prints and drawings by Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode in 1800 did much to raise the museum's reputation; but Montagu House became increasingly crowded and decrepit and it was apparent that it would be unable to cope with further expansion.[21]

The museum's first notable addition towards its collection of antiquities, since its foundation, was by Sir William Hamilton (1730–1803), British Ambassador to Naples, who sold his collection of Greek and Roman artefacts to the museum in 1784 together with a number of other antiquities and natural history specimens. A list of donations to the museum, dated 31 January 1784, refers to the Hamilton bequest of a "Colossal Foot of an Apollo in Marble". It was one of two antiquities of Hamilton's collection drawn for him by Francesco Progenie, a pupil of Pietro Fabris, who also contributed a number of drawings of Mount Vesuvius sent by Hamilton to the Royal Society in London.

Growth and change (1800–1825)

In the early 19th century the foundations for the extensive collection of sculpture began to be laid and Greek, Roman and Egyptian artefacts dominated the antiquities displays. After the defeat of the French campaign in the Battle of the Nile, in 1801, the British Museum acquired more Egyptian sculptures and in 1802 King George III presented the Rosetta Stone – key to the deciphering of hieroglyphs.[22] Gifts and purchases from Henry Salt, British consul general in Egypt, beginning with the Colossal bust of Ramesses II in 1818, laid the foundations of the collection of Egyptian Monumental Sculpture.[23] Many Greek sculptures followed, notably the first purpose-built exhibition space, the Charles Towneley collection, much of it Roman Sculpture, in 1805. In 1806, Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1799 to 1803 removed the large collection of marble sculptures from the Parthenon, on the Acropolis in Athens and transferred them to the UK. In 1816 these masterpieces of western art, were acquired by The British Museum by Act of Parliament and deposited in the museum thereafter.[24] The collections were supplemented by the Bassae frieze from Phigaleia, Greece in 1815. The Ancient Near Eastern collection also had its beginnings in 1825 with the purchase of Assyrian and Babylonian antiquities from the widow of Claudius James Rich.[25]

In 1802 a buildings committee was set up to plan for expansion of the museum, and further highlighted by the donation in 1822 of the King's Library, personal library of King George III's, comprising 65,000 volumes, 19,000 pamphlets, maps, charts and topographical drawings.[26] The neoclassical architect, Sir Robert Smirke, was asked to draw up plans for an eastern extension to the museum "... for the reception of the Royal Library, and a Picture Gallery over it ..."[27] and put forward plans for today's quadrangular building, much of which can be seen today. The dilapidated Old Montagu House was demolished and work on the King's Library Gallery began in 1823. The extension, the East Wing, was completed by 1831. However, following the founding of the National Gallery, London in 1824,[e] the proposed Picture Gallery was no longer needed, and the space on the upper floor was given over to the Natural history collections.[28]

The largest building site in Europe (1825–1850)

The museum became a construction site as Sir Robert Smirke's grand neo-classical building gradually arose. The King's Library, on the ground floor of the East Wing, was handed over in 1827, and was described as one of the finest rooms in London. Although it was not fully open to the general public until 1857, special openings were arranged during The Great Exhibition of 1851. In spite of dirt and disruption the collections grew, outpacing the new building.[citation needed]

In 1840, the museum became involved in its first overseas excavations, Charles Fellows's expedition to Xanthos, in Asia Minor, whence came remains of the tombs of the rulers of ancient Lycia, among them the Nereid and Payava monuments. In 1857, Charles Newton was to discover the 4th-century BC Mausoleum of Halikarnassos, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. In the 1840s and 1850s the museum supported excavations in Assyria by A.H. Layard and others at sites such as Nimrud and Nineveh. Of particular interest to curators was the eventual discovery of Ashurbanipal's great library of cuneiform tablets, which helped to make the museum a focus for Assyrian studies.[29]

Sir Thomas Grenville (1755–1846), a trustee of the British Museum from 1830, assembled a library of 20,240 volumes, which he left to the museum in his will. The books arrived in January 1847 in twenty-one horse-drawn vans. The only vacant space for this large library was a room originally intended for manuscripts, between the Front Entrance Hall and the Manuscript Saloon. The books remained here until the British Library moved to St Pancras in 1998.

Collecting from the wider world (1850–1875)

The opening of the forecourt in 1852 marked the completion of Robert Smirke's 1823 plan, but already adjustments were having to be made to cope with the unforeseen growth of the collections. Infill galleries were constructed for Assyrian sculptures and Sydney Smirke's Round Reading Room, with space for a million books, opened in 1857. Because of continued pressure on space the decision was taken to move natural history to a new building in South Kensington, which would later become the British Museum of Natural History.

Roughly contemporary with the construction of the new building was the career of a man sometimes called the "second founder" of the British Museum, the Italian librarian Anthony Panizzi. Under his supervision, the British Museum Library (now part of the British Library) quintupled in size and became a well-organised institution worthy of being called a national library, the largest library in the world after the National Library of Paris.[15] The quadrangle at the centre of Smirke's design proved to be a waste of valuable space and was filled at Panizzi's request by a circular Reading Room of cast iron, designed by Smirke's brother, Sydney Smirke.[30]

Until the mid-19th century, the museum's collections were relatively circumscribed but, in 1851, with the appointment to the staff of Augustus Wollaston Franks to curate the collections, the museum began for the first time to collect British and European medieval antiquities, prehistory, branching out into Asia and diversifying its holdings of ethnography. A real coup for the museum was the purchase in 1867, over French objections, of the Duke of Blacas's wide-ranging and valuable collection of antiquities. Overseas excavations continued and John Turtle Wood discovered the remains of the 4th century BC Temple of Artemis at Ephesos, another Wonder of the Ancient World.[31]

Scholarship and legacies (1875–1900)

The natural history collections were an integral part of the British Museum until their removal to the new British Museum of Natural History in 1887, nowadays the Natural History Museum. With the departure and the completion of the new White Wing (fronting Montague Street) in 1884, more space was available for antiquities and ethnography and the library could further expand. This was a time of innovation as electric lighting was introduced in the Reading Room and exhibition galleries.[32]

The William Burges collection of armoury was bequeathed to the museum in 1881. In 1882, the museum was involved in the establishment of the independent Egypt Exploration Fund (now Society) the first British body to carry out research in Egypt. A bequest from Miss Emma Turner in 1892 financed excavations in Cyprus. In 1897 the death of the great collector and curator, A. W. Franks, was followed by an immense bequest of 3,300 finger rings, 153 drinking vessels, 512 pieces of continental porcelain, 1,500 netsuke, 850 inro, over 30,000 bookplates and miscellaneous items of jewellery and plate, among them the Oxus Treasure.[33]

In 1898 Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild bequeathed the Waddesdon Bequest, the glittering contents from his New Smoking Room at Waddesdon Manor. This consisted of almost 300 pieces of objets d'art et de vertu which included exquisite examples of jewellery, plate, enamel, carvings, glass and maiolica, among them the Holy Thorn Reliquary, probably created in the 1390s in Paris for John, Duke of Berry. The collection was in the tradition of a schatzkammer or treasure house such as those formed by the Renaissance princes of Europe.[34] Baron Ferdinand's will was most specific, and failure to observe the terms would make it void, the collection should be

placed in a special room to be called the Waddesdon Bequest Room separate and apart from the other contents of the Museum and thenceforth for ever thereafter, keep the same in such room or in some other room to be substituted for it.[34]

These terms are still observed, and the collection occupies room 45, although it moved to new quarters in 2015.

New century, new building (1900–1925)

By the last years of the 19th century, The British Museum's collections had increased to the extent that its building was no longer large enough. In 1895 the trustees purchased the 69 houses surrounding the museum with the intention of demolishing them and building around the west, north and east sides of the museum. The first stage was the construction of the northern wing beginning 1906.

All the while, the collections kept growing. Emil Torday collected in Central Africa, Aurel Stein in Central Asia, D.G. Hogarth, Leonard Woolley and T. E. Lawrence excavated at Carchemish. Around this time, the American collector and philanthropist J Pierpont Morgan donated a substantial number of objects to the museum,[35] including William Greenwell's collection of prehistoric artefacts from across Europe which he had purchased for £10,000 in 1908. Morgan had also acquired a major part of Sir John Evans's coin collection, which was later sold to the museum by his son John Pierpont Morgan Junior in 1915. In 1918, because of the threat of wartime bombing, some objects were evacuated via the London Post Office Railway to Holborn, the National Library of Wales (Aberystwyth) and a country house near Malvern. On the return of antiquities from wartime storage in 1919 some objects were found to have deteriorated. A conservation laboratory was set up in May 1920 and became a permanent department in 1931. It is today the oldest in continuous existence.[36] In 1923, the British Museum welcomed over one million visitors.

Disruption and reconstruction (1925–1950)

New mezzanine floors were constructed and book stacks rebuilt in an attempt to cope with the flood of books. In 1931, the art dealer Sir Joseph Duveen offered funds to build a gallery for the Parthenon sculptures. Designed by the American architect John Russell Pope, it was completed in 1938. The appearance of the exhibition galleries began to change as dark Victorian reds gave way to modern pastel shades.[f] However, in August 1939, due to the imminence of war and the likelihood of air-raids, the Parthenon Sculptures, along with the museum's most valued collections, were dispersed to secure basements, country houses, Aldwych Underground station, the National Library of Wales and a quarry. The evacuation was timely, for in 1940 the Duveen Gallery was severely damaged by bombing.[38] Meanwhile, prior to the war, the Nazis had sent a researcher to the British Museum for several years with the aim of "compiling an anti-Semitic history of Anglo-Jewry."[39] After the war, the museum continued to collect from all countries and all centuries: among the most spectacular additions were the 2600 BC Mesopotamian treasure from Ur, discovered during Leonard Woolley's 1922–34 excavations. Gold, silver and garnet grave goods from the Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo (1939) and late Roman silver tableware from Mildenhall, Suffolk (1946). The immediate post-war years were taken up with the return of the collections from protection and the restoration of the museum after the Blitz. Work also began on restoring the damaged Duveen Gallery.

A new public face (1950–1975)

In 1953, the museum celebrated its bicentenary. Many changes followed: the first full-time in house designer and publications officer were appointed in 1964, the Friends organisation was set up in 1968, an Education Service established in 1970 and publishing house in 1973. In 1963, a new Act of Parliament introduced administrative reforms. It became easier to lend objects, the constitution of the board of trustees changed and the Natural History Museum became fully independent. By 1959 the Coins and Medals office suite, completely destroyed during the war, was rebuilt and re-opened, attention turned towards the gallery work with new tastes in design leading to the remodelling of Robert Smirke's Classical and Near Eastern galleries.[40] In 1962 the Duveen Gallery was finally restored and the Parthenon Sculptures were moved back into it, once again at the heart of the museum.[g]

By the 1970s the museum was again expanding. More services for the public were introduced; visitor numbers soared, with the temporary exhibition "Treasures of Tutankhamun" in 1972, attracting 1,694,117 visitors, the most successful in British history. In the same year the Act of Parliament establishing the British Library was passed, separating the collection of manuscripts and printed books from the British Museum. This left the museum with antiquities; coins, medals and paper money; prints & drawings; and ethnography. A pressing problem was finding space for additions to the library which now required an extra 1 1⁄4 miles (2.0 km) of shelving each year. The Government suggested a site at St Pancras for the new British Library but the books did not leave the museum until 1997.

The Great Court emerges (1975–2000)

The departure of the British Library to a new site at St Pancras, finally achieved in 1998, provided the space needed for the books. It also created the opportunity to redevelop the vacant space in Robert Smirke's 19th-century central quadrangle into the Queen Elizabeth II Great Court – the largest covered square in Europe – which opened in 2000. The ethnography collections, which had been housed in the short-lived Museum of Mankind at 6 Burlington Gardens from 1970, were returned to new purpose-built galleries in the museum in 2000.

The museum again readjusted its collecting policies as interest in "modern" objects: prints, drawings, medals and the decorative arts reawakened. Ethnographical fieldwork was carried out in places as diverse as New Guinea, Madagascar, Romania, Guatemala and Indonesia and there were excavations in the Near East, Egypt, Sudan and the UK. The Weston Gallery of Roman Britain, opened in 1997, displayed a number of recently discovered hoards which demonstrated the richness of what had been considered an unimportant part of the Roman Empire. The museum turned increasingly towards private funds for buildings, acquisitions and other purposes.[42]

The British Museum today

Today the museum no longer houses collections of natural history, and the books and manuscripts it once held now form part of the independent British Library. The museum nevertheless preserves its universality in its collections of artefacts representing the cultures of the world, ancient and modern. The original 1753 collection has grown to over thirteen million objects at the British Museum, 70 million at the Natural History Museum and 150 million at the British Library.

The Round Reading Room, which was designed by the architect Sydney Smirke, opened in 1857. For almost 150 years researchers came here to consult the museum's vast library. The Reading Room closed in 1997 when the national library (the British Library) moved to a new building at St Pancras. Today it has been transformed into the Walter and Leonore Annenberg Centre.

With the bookstacks in the central courtyard of the museum empty, the demolition for Lord Foster's glass-roofed Great Court could begin. The Great Court, opened in 2000, while undoubtedly improving circulation around the museum, was criticised for having a lack of exhibition space at a time when the museum was in serious financial difficulties and many galleries were closed to the public. At the same time the African collections that had been temporarily housed in 6 Burlington Gardens were given a new gallery in the North Wing funded by the Sainsbury family – with the donation valued at £25 million.[43]

As part of its very large website, the museum has the largest online database of objects in the collection of any museum in the world, with 2,000,000 individual object entries, 650,000 of them illustrated, online at the start of 2012.[44] There is also a "Highlights" database with longer entries on over 4,000 objects, and several specialised online research catalogues and online journals (all free to access).[45] In 2013 the museum's website received 19.5 millions visits, an increase of 47% from the previous year.[46]

In 2013 the museum received a record 6.7 million visitors, an increase of 20% from the previous year.[46] Popular exhibitions including "Life and Death in Pompeii and Herculaneum" and "Ice Age Art" are credited with helping fuel the increase in visitors.[47] Plans were announced in September 2014 to recreate the entire building along with all exhibits in the video game Minecraft in conjunction with members of the public.[48]

Le British Museum (en français « Musée britannique », appellation couramment utilisée jusqu'au XXe siècle, mais devenue rare), est un musée de l'histoire et de la culture humaine, situé à Londres, au Royaume-Uni. Ses collections, constituées de plus de sept millions d’objets, sont parmi les plus importantes du monde et proviennent de tous les continents. Elles illustrent l’histoire humaine de ses débuts à aujourd'hui.

Le musée a été fondé en 1753 et ouvert au public en 1759. Son statut actuel de non-departmental public body lui permet d’être financé par le département de la Culture, des Médias et du Sport. Le British Museum compte six millions de visiteurs par an et s'affiche comme le site touristique le plus fréquenté de Grande-Bretagne. Comme dans la plupart des musées et galeries d’art du Royaume-Uni, l’entrée est gratuite, à l’exception de certaines expositions temporaires ; les dons sont encouragés.

Le British Museum fut créé en 1753, à partir notamment des collections du médecin et scientifique Sir Hans Sloane. Le musée a été ouvert au public le 15 janvier 1759 à la Montagu House à Bloomsbury, au même emplacement qu'aujourd'hui ; il comptait alors quelque 80 000 objets. Les collections s’enrichirent notamment avec les contributions du capitaine Cook, et de William Hamilton (archéologue et diplomate britannique). La défaite de Napoléon en Égypte (campagne d'Égypte) permit d’acquérir des pièces d'art égyptiennes, dont la <

Nationen nach Anzahl der Siege und FinalteilnahmenRangLandSiegeFinal-

| Rang | Land | Siege | Final- niederlagen |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 32 | 29 | |

| 2. | 28* | 19 | |

| 3. | 10 | 9 | |

| 4. | 10 | 8 | |

| 5. | 7 | 5 | |

| 6. | 6 | 4 | |

| 7. | 3 | 3 | |

| 8. | 3 | 2 | |

| 3** | 2 | ||

| 10. | 2 | 2 | |

| 11. | 1 | 6 | |

| 12. | 1 | 4 | |

| 13. | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 15. | 1 | 0 | |

| 16. | 0 | 3 | |

| 0 | 3 | ||

| 0 | 3 | ||

| 19. | 0 | 1 | |

| 0 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 1 | ||

| 0 | 1 |

* inkl. vier Siegen als Australasien

** inkl. eines Sieges als Tschechoslowakei

历史

历史

法律

法律

建筑艺术

建筑艺术

艺术

艺术

博物馆

博物馆

企业

企业

能源

能源

体育

体育

信息时代

信息时代

国际城市

国际城市

生活时尚

生活时尚

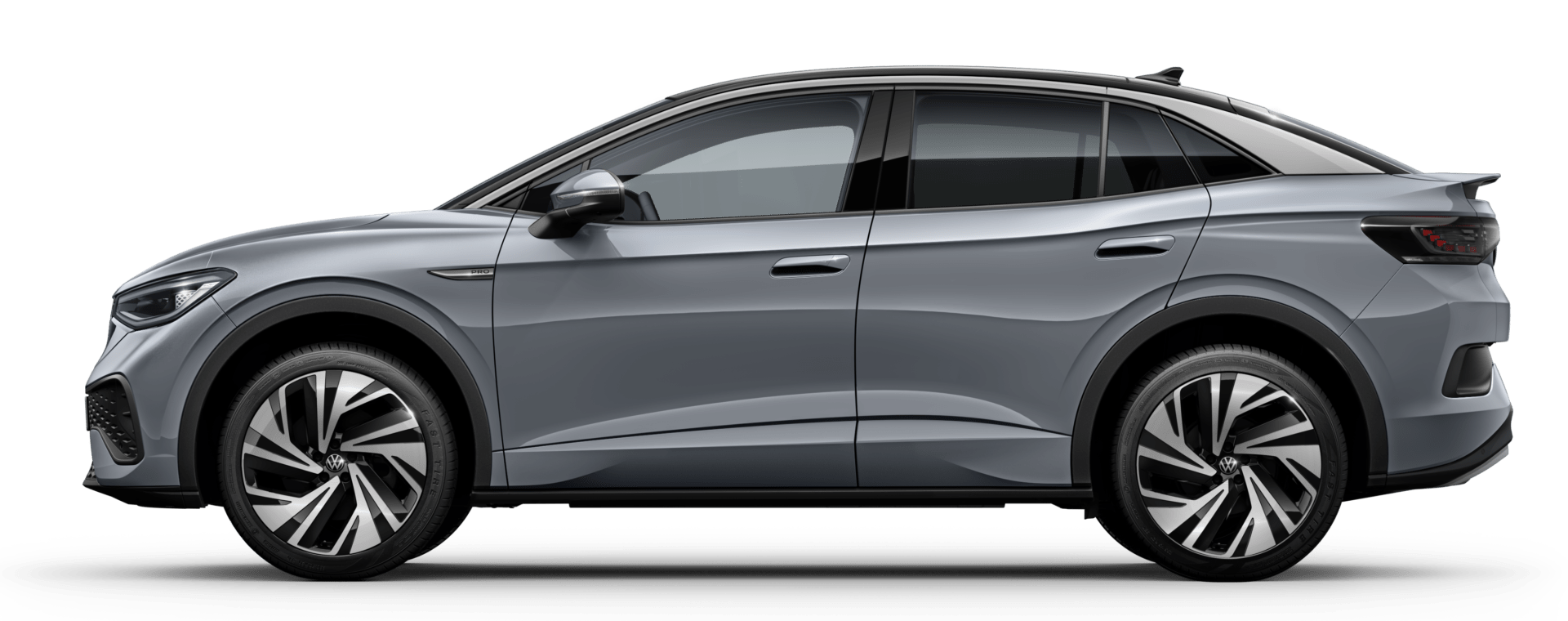

汽车

汽车