Deutsch-Chinesische Enzyklopädie, 德汉百科

Gansu Sheng-GS

Gansu Sheng-GS

Beijing Shi-BJ

Beijing Shi-BJ

Belarus

Belarus

Berlin

Berlin

Brandenburg

Brandenburg

Bremen

Bremen

China

China

Germany

Germany

France

France

Gansu Sheng-GS

Gansu Sheng-GS

Hamburg

Hamburg

Hebei Sheng-HE

Hebei Sheng-HE

Heilongjiang Sheng-HL

Heilongjiang Sheng-HL

Henan Sheng-HA

Henan Sheng-HA

Hubei Sheng-HB

Hubei Sheng-HB

Hunan Sheng-HN

Hunan Sheng-HN

Iran

Iran

Italy

Italy

Jilin Sheng-JL

Jilin Sheng-JL

Kasachstan

Kasachstan

Liaoning Sheng-LN

Liaoning Sheng-LN

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Netherlands

Netherlands

Lower Saxony

Lower Saxony

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

North Rhine-Westphalia

North Rhine-Westphalia

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Russia

Russia

Saxony

Saxony

Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shandong Sheng-SD

Shandong Sheng-SD

Shanxi Sheng-SX

Shanxi Sheng-SX

Sichuan Sheng-SC

Sichuan Sheng-SC

Spain

Spain

Turkey

Turkey

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

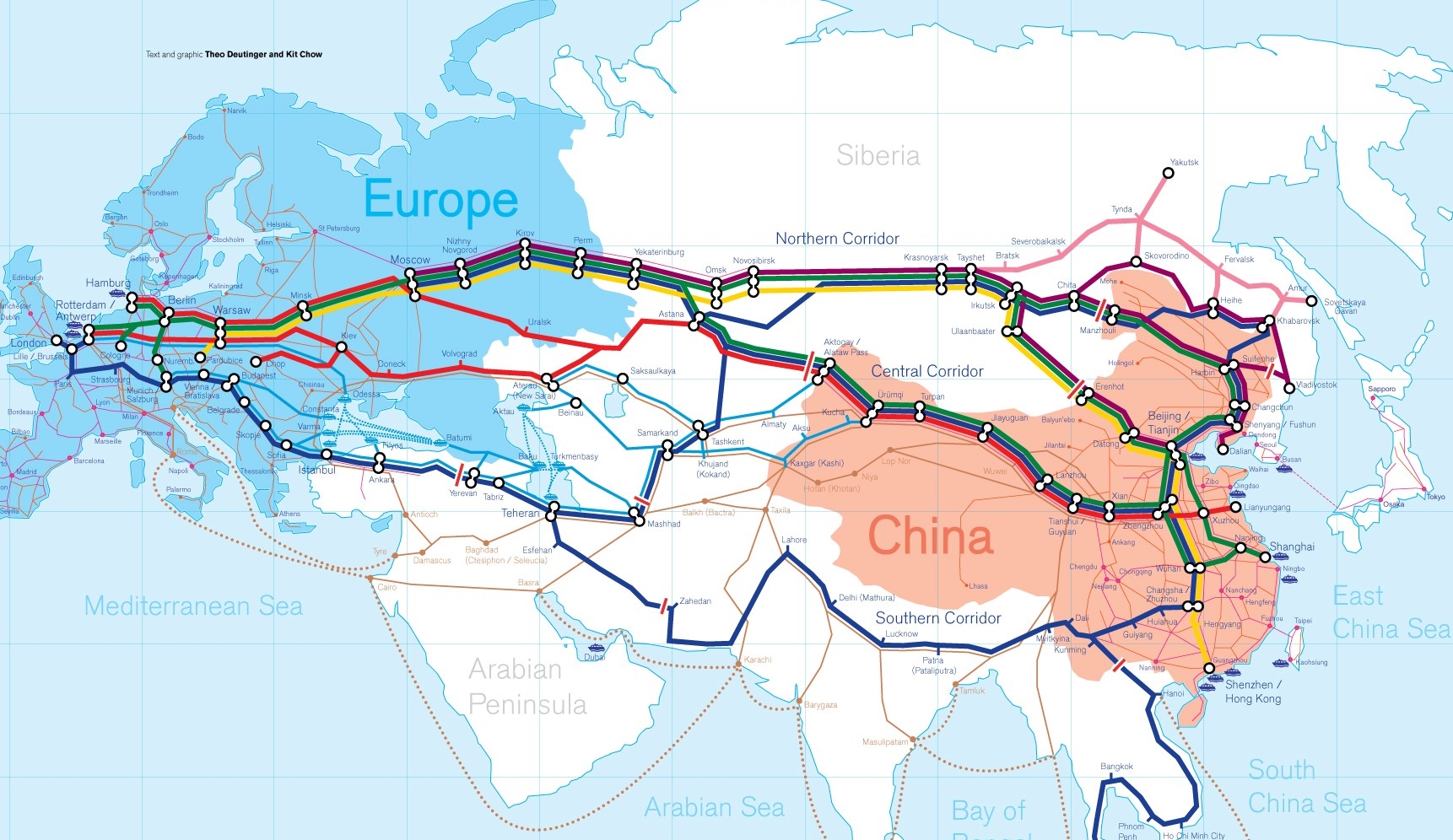

Die Neue eurasische Kontinentalbrücke (chinesisch 新亚欧大陆桥, Pinyin Xīn Yà-Ōu Dàlù Qiáo, englisch New Eurasian Continental Bridge), die auch Zweite eurasische Kontinentalbrücke (第二亚欧大陆桥, Dì'èr Yà-Ōu Dàlù Qiáo, englisch Second Eurasian Continental Bridge) genannt wird, ist eine 10.870 Kilometer[1] lange Eisenbahnverbindung, die Rotterdam in Europa mit der ostchinesischen Hafenstadt Lianyungang in der Provinz Jiangsu verbindet.

Sie besteht seit 1990 und führt durch die Dsungarische Pforte (Grenzbahnhof Alashankou). Die Lan-Xin-Bahn (chinesisch 兰新铁路, Pinyin Lán-Xīn Tiělù), also die Strecke von Lanzhou nach Ürümqi (in Xinjiang), ist ein Teil von ihr.

Es gibt eine nördliche, mittlere und südliche Route.[2] Die mittlere Strecke verläuft durch Kasachstan über Dostyk, Aqtogai, Astana, Samara, Smolensk, Brest, Warschau, Berlin zum Hafen von Rotterdam.[3] Vom slowakischen Košice soll auch eine Abzweigung in den Großraum Wien führen, siehe Breitspurstrecke Košice–Wien.

The New Eurasian Land Bridge, also called the Second or New Eurasian Continental Bridge, is the southern branch of the Eurasian Land Bridge rail links running through China. The Eurasian Land Bridge is the overland rail link between Asia and Europe.

Due to a break-of-gauge between standard gauge used in China and the Russian gauge used in the former Soviet Union countries, containers must be physically transferred from Chinese to Kazakh railway cars at Dostyk on the Chinese-Kazakh border and again at the Belarus-Poland border where the standard gauge used in western Europe begins. This is done with truck-mounted cranes.[1] Chinese media often states that the New Eurasian Land/Continental Bridge extends from Lianyungang to Rotterdam, a distance of 11,870 kilometres (7,380 mi). The exact route used to connect the two cities is not always specified in Chinese media reports, but appears to usually refer to the route which passes through Kazakhstan.

All rail freight from China across the Eurasian Land Bridge must pass north of the Caspian Sea through Russia at some point. A proposed alternative would pass through Turkey and Bulgaria,[2] but any route south of the Caspian Sea must pass through Iran.[1]

Kazakhstan's President Nursultan Nazarbayev urged Eurasian and Chinese leaders at the 18th Shanghai Cooperation Organisation to construct the Eurasian high-speed railway (EHSRW) following a Beijing-Astana-Moscow-Berlin.[3]

The Eurasian Land Bridge (Russian: Евразийский сухопутный мост, Yevraziyskiy sukhoputniy most), sometimes called the New Silk Road (Новый шёлковый путь, Noviy shyolkoviy put'), or Belt and Road Initiative is the rail transport route for moving freight and passengers overland between Pacific seaports in the Russian Far East and China and seaports in Europe. The route, a transcontinental railroad and rail land bridge, currently comprises the Trans-Siberian Railway, which runs through Russia and is sometimes called the Northern East-West Corridor, and the New Eurasian Land Bridge or Second Eurasian Continental Bridge, running through China and Kazakhstan. As of November 2007, about 1% of the $600 billion in goods shipped from Asia to Europe each year were delivered by inland transport routes.[1]

Completed in 1916, the Trans-Siberian connects Moscow with Russian Pacific seaports such as Vladivostok. From the 1960s until the early 1990s the railway served as the primary land bridge between Asia and Europe, until several factors caused the use of the railway for transcontinental freight to dwindle. One factor is that the railways of the former Soviet Union use a wider rail gauge than most of the rest of Europe as well as China. Recently, however, the Trans-Siberian has regained ground as a viable land route between the two continents.[why?]

China's rail system had long linked to the Trans-Siberian via northeastern China and Mongolia. In 1990 China added a link between its rail system and the Trans-Siberian via Kazakhstan. China calls its uninterrupted rail link between the port city of Lianyungang and Kazakhstan the New Eurasian Land Bridge or Second Eurasian Continental Bridge. In addition to Kazakhstan, the railways connect with other countries in Central Asia and the Middle East, including Iran. With the October 2013 completion of the rail link across the Bosphorus under the Marmaray project the New Eurasian Land Bridge now theoretically connects to Europe via Central and South Asia.

Proposed expansion of the Eurasian Land Bridge includes construction of a railway across Kazakhstan that is the same gauge as Chinese railways, rail links to India, Burma, Thailand, Malaysia and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, construction of a rail tunnel and highway bridge across the Bering Strait to connect the Trans-Siberian to the North American rail system, and construction of a rail tunnel between South Korea and Japan. The United Nations has proposed further expansion of the Eurasian Land Bridge, including the Trans-Asian Railway project.

El Nuevo Puente de Tierra de Eurasia es también llamado el Segundo o Nuevo Puente Continental de Eurasia. Es la rama meridional de las conexiones ferroviarias del Puente de Tierra de Eurasia (también conocido como "Nueva Ruta de la Seda") que se extienden a través de la República Popular China, atravesando Kazajistán, Rusia y Bielorrusia. El Puente de Tierra de Eurasia es el enlace ferroviario terrestre entre Asia Oriental y Europa.

La Nueva Ruta de la Seda (en ruso, Новый шёлковый путь, Noviy shyolkoviy put), o Puente Terrestre Euroasiático, es la ruta de transporte ferroviario para el movimiento de tren de mercancías y tren de pasajeros por tierra entre los puertos del Pacífico, en el Lejano Oriente ruso y chino y los puertos marítimos en Europa.

La ruta, un ferrocarril transcontinental y puente terrestre, actualmente comprende el ferrocarril Transiberiano, que se extiende a través de Rusia, y el nuevo puente de tierra de Eurasia o segundo puente continental de Eurasia, que discurre a través de China y Kazajistán, también se van a construir carreteras entre las ciudades de la ruta. A partir de noviembre de 2007, aproximadamente el 1% de los 600 millones de dólares en bienes enviados desde Asia a Europa cada año se entregaron por vías de transporte terrestre.1

Terminado en 1916, el tren Transiberiano conecta Moscú con el lejano puerto de Vladivostok en el océano Pacífico, el más largo del mundo en el Lejano Oriente e importante puerto del Pacífico. Desde la década de 1960 hasta principios de 1990 el ferrocarril sirvió como el principal puente terrestre entre Asia y Europa, hasta que varios factores hicieron que el uso de la vía férrea transcontinental para el transporte de carga disminuyese.

Un factor es que los ferrocarriles de la Unión Soviética utilizan un ancho de vía más ancho en los rieles que la mayor parte del resto de Europa y China, y el transporte en barcos de carga por el canal de Suez en Egipto, construido por Inglaterra. El sistema ferroviario de China se une al Transiberiano en el noreste de China y Mongolia. En 1990 China añadió un enlace entre su sistema ferroviario y el Transiberiano a través de Kazajistán. China denomina a su enlace ferroviario ininterrumpido entre la ciudad portuaria de Lianyungang y Kazajistán como el «Puente terrestre de Nueva Eurasia» o «Segundo puente continental Euroasiático». Además de Kazajistán, los ferrocarriles conectan con otros países de Asia Central y Oriente Medio, incluyendo a Irán. Con la finalización en octubre de 2013 de la línea ferroviaria a través del Bósforo en el marco del proyecto Marmaray el puente de tierra de Nueva Eurasia conecta ahora teóricamente a Europa a través de Asia Central y del Sur.

La propuesta de ampliación del Puente Terrestre Euroasiático incluye la construcción de un ferrocarril a través de Kazajistán con el mismo ancho de vía que los ferrocarriles chinos, enlaces ferroviarios a la India, Birmania, Tailandia, Malasia y otros países del sudeste asiático, la construcción de un túnel ferroviario y un puente de carretera a través del estrecho de Bering para conectar el Transiberiano al sistema ferroviario de América del Norte, y la construcción de un túnel ferroviario entre Corea del Sur y Japón. Las Naciones Unidas ha propuesto una mayor expansión del Puente Terrestre Euroasiático, incluyendo el proyecto del ferrocarril transasiático.

Новый шёлковый путь (Евразийский сухопутный мост — концепция новой паневразийской (в перспективе — межконтинентальной) транспортной системы, продвигаемой Китаем, в сотрудничестве с Казахстаном, Россией и другими странами, для перемещения грузов и пассажиров по суше из Китая в страны Европы. Транспортный маршрут включает трансконтинентальную железную дорогу — Транссибирскую магистраль, которая проходит через Россию и второй Евразийский континентальный мост[en], проходящий через Казахстан[1]. Поезда по этому самому длинному в мире грузовому железнодорожному маршруту из Китая в Германию будут идти 15 дней, что в 2 раза быстрее, чем по морскому маршруту через Суэцкий канал[2].

Идея Нового шёлкового пути основывается на историческом примере древнего Великого шёлкового пути, действовавшего со II в. до н. э. и бывшего одним из важнейших торговых маршрутов в древности и в средние века. Современный НШП является важнейшей частью стратегии развития Китая в современном мире — Новый шёлковый путь не только должен выстроить самые удобные и быстрые транзитные маршруты через центр Евразии, но и усилить экономическое развитие внутренних регионов Китая и соседних стран, а также создать новые рынки для китайских товаров (по состоянию на ноябрь 2007 года, около 1 % от товаров на 600 млрд долл. из Азии в Европу ежегодно доставлялись наземным транспортом[3]).

Китай продвигает проект «Нового шёлкового пути» не просто как возрождение древнего Шёлкового пути, транспортного маршрута между Востоком и Западом, но как масштабное преобразование всей торгово-экономической модели Евразии, и в первую очередь — Центральной и Средней Азии. Китайцы называют эту концепцию — «один пояс — один путь». Она включает в себя множество инфраструктурных проектов, которые должны в итоге опоясать всю планету. Проект всемирной системы транспортных коридоров соединяет Австралию и Индонезию, всю Центральную и Восточную Азию, Ближний Восток, Европу, Африку и через Латинскую Америку выходит к США. Среди проектов в рамках НШП планируются железные дороги и шоссе, морские и воздушные пути, трубопроводы и линии электропередач, и вся сопутствующая инфраструктура. По самым скромным оценкам, НШП втянет в свою орбиту 4,4 миллиарда человек — более половины населения Земли[4].

Предполагаемое расширение Евразийского сухопутного моста включает в себя строительство железнодорожных путей от трансконтинентальных линий в Иран, Индию, Мьянму, Таиланд, Пакистан, Непал, Афганистан и Малайзию, в другие регионы Юго-Восточной Азии и Закавказья (Азербайджан, Грузия). Маршрут включает тоннель Мармарай под проливом Босфор, паромные переправы через Каспийское море (Азербайджан-Иран-Туркменистан-Казахстан) и коридор Север-Юг.Организация Объединенных Наций предложила дальнейшее расширение Евразийского сухопутного моста, в том числе проекта Трансазиатской железной дороги (фактически существует уже в 2 вариантах).

Для развития инфраструктурных проектов в странах вдоль Нового шёлкового пути и Морского Шёлкового пути и с целью содействия сбыту китайской продукции в декабре 2014 года был создан инвестиционный Фонд Шёлкового пути[5].

8 мая 2015 года было подписано совместное заявление Президента РФ В. Путина и Председателя КНР Си Цзиньпина о сотрудничестве России и Китая, в рамках ЕАЭС и трансевразийского торгово-инфраструктурного проекта экономического пояса «Шёлковый путь». 13 июня 2015 года был запущен самый длинный в мире грузовой железнодорожный маршрут Харбин — Гамбург (Германия), через территорию России.

Gansu Sheng-GS

Gansu Sheng-GS

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Northwest China

Northwest China

Qinghai Sheng-QH

Qinghai Sheng-QH

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

Xinjiang Uygur Zizhiqu-XJ

*Yellow river

*Yellow river

Gansu Sheng-GS

Gansu Sheng-GS

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shaanxi Sheng-SN

Shanxi Sheng-SX

Shanxi Sheng-SX

*Yellow river

*Yellow river

China

China

Gansu Sheng-GS

Gansu Sheng-GS

Hebei Sheng-HE

Hebei Sheng-HE

Mongolei

Mongolei

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Nei Mongol Zizhiqu-NM

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

Ningxia Huizu Zizhiqu-NX

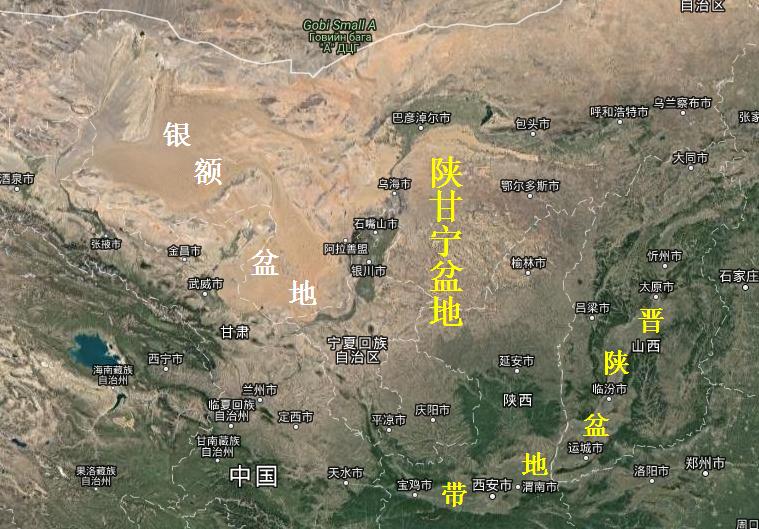

Das Plateau der Inneren Mongolei (內蒙古高原, Nei Menggu gaoyuan) ist ein sich quer über den Norden Chinas erstreckendes Hochland. Zusammen mit seiner west- und nördlichen Fortsetzung (Mongolisches Plateau) ist es das zweitgrößte Hochland Chinas nach dem Qinghai-Tibet-Plateau. Es reicht im Osten vom Großen Hinggan-Gebirge bis im Westen zum Mazu-Gebirge (馬鬃山 Mazu Shan) und Sukexielu Shan 苏克斜鲁山, im Süden entlang der Großen Mauer und im Norden grenzt es an die Mongolische Volksrepublik.

Das Plateau der Inneren Mongolei umfasst das gesamte Gebiet der Inneren Mongolei und einen Teil von Gansu, Ningxia und Hebei. Von West nach Ost ist es über 2000 Kilometer lang und von Nord nach Süd ca. 500 Kilometer. Das Plateau ist im Allgemeinen 1000 bis 1400 m hoch. Im Osten ist es niederschlagsreicher als im Westen.

Den Südteil des Plateaus bilden das Ordos-Plateau (鄂爾多斯高原) und die schmale fruchtbare Hetao-Ebene (河套平原, Hetao pingyuan). Im Ostteil und Nordteil liegen das Hulun-Buir-Plateau (呼倫貝爾高原), das Ujumqin-Becken (乌珠穆沁盆地, Wuzhumuqin pendi), das Xilin-Gol-Plateau (錫林郭勒高原) und das Ulanqab-Plateau (烏蘭察布高原), im Westen das Bayan-Nur-Plateau (巴彥淖爾高原) und das Alxa-Plateau (阿拉善高原). Das in Ostwest-Richtung verlaufende Yinshan-Gebirge (阴山, Yin Shan) liegt in seiner Mitte.

祁家黄河大桥于2006年8月9日开工建设,2009年9月19日建成通车,完成投资4200万元。项目起于永靖县刘家峡镇,止于东乡县董岭乡祁家村,全长828米,其中桥长248米,设计速度为40公里/小时,桥宽12米,桥梁设计荷载为公路-Ⅰ级。

祁家黄河大桥是我省国道干线公路上最后一座渡改桥工程,它的建成通车彻底结束了祁家黄河渡口摆渡带来的各种不便与安全隐患,使黄河两岸的永靖县和东乡县通车时间缩短了近1小时,大大提高了国道213线的通行水平和安全保障能力。

Das Qilian-Gebirge liegt im Durchschnitt 4 000–5 000 m hoch. Lange und breite Gletscher bestimmen die Landschaft. Die Schneegrenze liegt bei 4 000 m. Normalerweise herrscht oberhalb der Schneegrenz eine ewige Schnee- und Eiswelt und selten findet man dort noch ein Lebewesen. Am Qilian-Gebirge ähneln die aus ewigem Schnee entstandenen Gletscher riesigen weißen „Hadas“. Wunderbarerweise wachsen oberhalb der Schneegrenze des Qilian-Gebirges eine pilzartige Pflanze namens „Canzhui“ und die Schneeglocke, die ein kostbares chinesisches Heilkraut ist. Unter einigen Felsen wächst auch das Schneegebirgsgras. Man nennt diese zusammen die „drei Freunde in der Kälte“.(Quelle:http://www.chinatoday.com.cn)

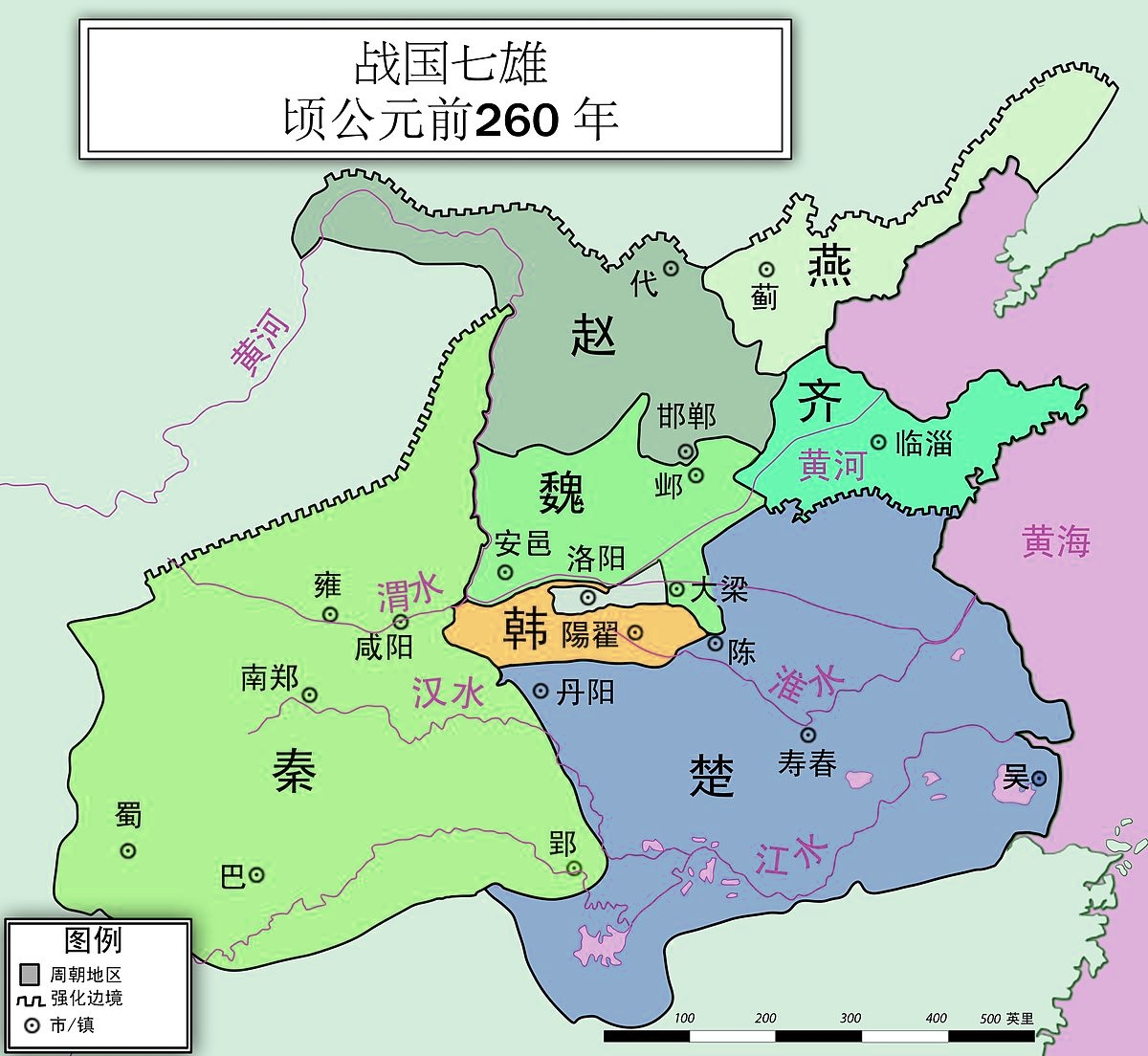

秦国是春秋战国时期诸侯国,嬴姓,赵氏[1][2]。史记秦本纪主要根据为秦人所自述历史。据被盗掘后抢救回来的清华简《系年》的第三章所载,周初三监之乱平定后,蜚廉“东逃于商奄氏。成王伐商奄,杀蜚廉,西迁商奄之民于邾,以御奴之戎,是秦先人”[3][4]。清华简本身为海外黑市购买,相对现场出土文物其真实性先天不足,受部分学术界人士质疑,如姜广辉在《光明日报》的质疑、房德邻在《中国文化报》指出简文使用了先秦不可能产生的双音词“瘇胀”。熊铁基认为秦人伪造家谱,丁山在《中国古代宗教与神话考》一书中则说夏、商、周、秦“四代开国前世系皆宗祝伪托”;金景芳认为“《史记三代世表》明确地谱列尧、舜和夏、殷、周王室的祖先同是以黄帝为初祖。虽然在细节上不能保证没有缺漏和讹误,但大体上说是有根据的,可信的。”雍际春、王宏谋说秦部落祖先是伯益,祝军指出秦部落是少昊的后裔,柳明瑞认为嬴秦氏族起源于今山东地区[5]。据史记秦本纪,西周周孝王因秦祖先非子善养马,因此将其封于秦,作为周朝分封国。前770年,秦襄公护送周平王东迁有功,获封为诸侯,为伯爵地位,秦正式成为一方诸侯国。周朝给其封地在今甘肃河东地区到陕西一带。从前677年起,秦国在雍(今甘肃天水到陇南一带)建都近300年。雍城遗址有宫殿区、居住区、士大夫与国人墓葬区和秦公陵园。

秦国与西戎、义渠之间有通婚、结盟的关系,秦国崛起后,这些势力皆被并入秦国。战国时期,秦孝公[6]实施商鞅变法,为秦灭六国奠定基础。秦王嬴政在前221年,统一诸夏,秦始皇使秦国成为中国历史上第一个大一统中央集权君主制帝国,秦帝国较西方的罗马帝国还要早两百年。

Qin (Chinese: 秦; Wade–Giles: Ch'in; Old Chinese: *[dz]i[n]) was an ancient Chinese state during the Zhou dynasty. Traditionally dated to 897 B.C.,[1] it took its origin in a reconquest of western lands previously lost to the Rong; its position at the western edge of Chinese civilization permitted expansion and development that was unavailable to its rivals in the North China Plain. Following extensive "Legalist" reform in the 3rd century BC, Qin emerged as one of the dominant powers of the Seven Warring States and unified China in 221 BC under Shi Huangdi. The empire it established was short-lived but greatly influential on later Chinese history.

Though disliked by many Confucians of its time for "dangerously lacking in Confucian scholars," Confucian Xun Kuang wrote of the later Qin that "its topographical features are inherently advantageous," and that its "'manifold natural resources gave it remarkable inherent strength. Its people were unspoiled and exceedingly deferential; its officers unfailingly respectful, earnest, reverential, loyal, and trustworthy; and its high officials public-spirited, intelligent, and assiduous in the execution of the duties of their position. Its courts and bureaus functioned without delays and with such smoothness that it was as if there were no government at all."[2]

L'État de Qin ou Ts'in (EFEO) (秦) (v. 771 av. J.-C. - 207 av. J.-C.) apparaît au début de la dynastie des Zhou Orientaux, dans la vallée de la Wei (actuelle province du Shaanxi). État semi-barbare aux confins occidentaux de la Chine des Zhou, son influence s'accroît au cours de la période des Printemps et des Automnes et surtout des Royaumes combattants, à la fin de laquelle le roi de Qin, ayant annexé ses six principaux rivaux (Qi, Chu, Han, Yan, Zhao, et Wei) fonde la dynastie Qin (221 av. J.-C.-207 av. J.-C.). La famille régnante du Qin portait le nom de Ying (嬴).

Qin o Ch'in (Wade-Giles) (秦), (778 a.C.-207 a.C.) fu uno Stato cinese del Periodo delle primavere e degli autunni e del Periodo dei regni combattenti. Il nome cinese per i suoi regnanti era Ying (嬴).

El estado Qin (en chino: 秦國, Wade-Giles: Ch'in2 kuo2, pinyin: Qín guó) era un estado en el noroeste de China que se extendió durante el periodo de Primaveras y Otoños y los Reinos Combatientes de la historia antigua. Surgió como una de las superpotencias dominantes de los siete estados combatientes por el siglo III a. C. y, finalmente unificó a China bajo su mandato en el año 221 a. C., después de lo cual se le conoció como la Dinastía Qin.

Цинь (кит. 秦) — царство в древнем Китае, которое сначала было удельным княжеством, а потом смогло объединить Китай (см. «Цинь (династия)»). Существовало от 778 до н. э. по 221 до н. э. в эпоху формального правления династии Чжоу в периоды Весны и Осени и Сражающихся царств до образования Империи Цинь. Правящая семья носила фамилию Ин (кит. 嬴).

Transport and traffic

Transport and traffic

Geography

Geography

Architecture

Architecture

Art

Art

History

History