Meine Kanäle - Kulturaustausch Ost-West|东西方文化交流|East-West cultural exchange|Échange culturel Est-Ouest

- Portrait gravé en frontispice de l'empereur Quianlong en premier volume.

- Le volume VII est une réimpression de l'Art militaire des Chinois d'Amiot (Paris, 1772), la première traduction dans une langue européenne de l'ancienne stratégie militaire chinoise.

- Le volume XII est entièrement consacré à la vie de Confucius avec de superbes planches.

France was one of the most energetic and creative nations in Western history. The ever-evolving French clothing tradition has remained an inspiration for fashionistas, says Abarrna Devi R.

Fashion is an integral part of the society and culture in France and acts as one of the core brand images for the country. Haute couture and pret-a-porter have French origins. France has produced many renowned designers and French designs have been dominating the fashion world since the 15th century. The French fashion industry has cultivated its reputation in style and innovation and remained an important cultural export for over four centuries. Designers like Gabrielle Bonheur 'Coco' Chanel, Christian Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, Thierry Herms and Louis Vuitton have founded some of the most famous and popular fashion brands.

In the 16th century, fashion clothing in France dealt with contrast fabrics, clashes, trims and other accessories. Silhouette, which refers to the line of a dress or the garment's overall shape, was wide and conical for women and square for men in the 1530s. Around the middle of that decade, a tall and narrow line with a V-shaped waist appeared. Focusing on the shoulder point, sleeves and skirts for women were widened. Ruffles got associated with neckband of a shirt and was shaped with clear folds. A ruffle, frill, or furbelow is a strip of fabric, lace or ribbon tightly gathered or pleated on one edge and applied to a garment, bedding, or other textile as a form of trimming.

Outer clothing for women was characterised by a loose or fitted gown over a petticoat. In the 1560s, trumpet sleeves were rejected and the silhouette became narrow and widened with concentration in shoulder and hip.

Between 1660 and 1700, the older silhouette was replaced by a long, lean line with a low waist for both men and women. A low-body, tightly-laced dress was plaited behind, with the petticoat looped upon a pannier (part of a skirt looped up round the hips) covered with a shirt. The dress was accompanied by black leather shoes. Winter dress for women was trimmed with fur. Overskirt was drawn back in later half of the decades, and pinned up with the heavily-decorated petticoat. But around 1650, full, loose sleeves became longer and tighter. The dress tightly hugged the body with a low and broad neckline and adjusted shoulder.

Men's clothing did not change much in the first half of the 17th century. In 1725, the skirts of the coat acted as a pannier. This was brought about by making five or six folds distended by paper or horsehair and by the black ribbon worn around the neck to give the effect of the frill. A hat carried under the arm and a wig added to the charm. At court ceremonies, women wore a large coat embroidered with gold that was open in the front and buttoned up with a belt or a waist band. The light coat was figure-hugging with tighter sleeves. It was projected in the back with a double row of silk or metal buttons in various shapes and sizes.

French fashion varied between 1750 and 1775. Elaborate court dresses with enchanting colours and decoration defined style. In the 1750s, the size of hoop skirts got smaller and was worn with formal dresses with side-hoops. Use of waistcoats and breeches continued. A low-neck gown was worn over a petticoat during this period. Sleeves were cut with frills or ruffles with fine linen attached to the smock sleeves. The neckline was fitted with trimmed fabric or lace ruffle and a neckerchief (scarf).

Fashion between 1795 and 1820 in European countries transformed into informal styles involving brocades and lace. It was distinctly different from earlier styles as well as from the ones seen in the latter half of the 19th century. Women's clothes were tight against the torso from the waist upwards and heavily full-skirted. The short-waist dresses adorned with soft, loose skirts were fabricated with white, transparent muslin. Evening gowns were trimmed and decorated with lace, ribbons and netting. Those were cut low with short sleeves.

In the 1800s, women's dressing was characterised by short hair with white hats, trim, feathers, lace, shawls and hooded-overcoats while men preferred linen shirts with high collars, tall hats and short and wigless hair.

In the 1810s, dress for women was designed with soft, subtle, sheer classical drapes with raised back waist and short-fitted single-breasted jackets. Their hair was parted in the centre and they wore tight ringlets in the ears. Men's dress was fabricated with single-breasted tailcoats, cravats (the forerunner of the necktie and bow tie) wrapped up to the chin with natural hair, tight breeches and silk stockings. Accessories included gold watches, canes and hats.

In the 1820s, women's dress came with waist lines that almost dropped with elaborate hem and neckline decoration, cone-shaped skirts and sleeves. Men's overcoats were designed with fur of velvet collars.

Fashion designers still get inspired by 18th century creations. The impact of the 'clothing revolution' changed the dynamics of history of clothing. Paris is a global fashion hub and despite competition from Italy, the United Kingdom, Spain and Germany, French citizens continue to maintain their indisputable image of modish, fashion-loving people.

About the author

Abarrna Devi R is a final year B. Tech student in the department of fashion technology in Bannari Amman Institute of Technology, Sathyamangalam, Coimbatore, and Tamil Nadu.

References

1. Dauncey, Hugh, ed., French Popular Culture: An Introduction, New York: Oxford University Press (Arnold Publishers), 2003.

2. DeJean, Joan, the Essence of Style: How the French Invented High Fashion, Fine Food, Chic Cafes, Style, Sophistication, and Glamour, New York: Free Press, 2005, ISBN978-0-7432-6413-6

3. Kelly, Michael, French Culture and Society: The Essentials, New York: Oxford University Press (Arnold Publishers), 2001, (a reference guide)

4. Nadeau, Jean-Benot and Julie Barlow, Sixty Million Frenchmen Can't Be Wrong: Why We Love France but Not the French, Sourcebooks Trade, 2003, ISBN1-4022-0045-5

5. Bourhis, Katell le: The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire, 1789-1815, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989. ISBN0870995707

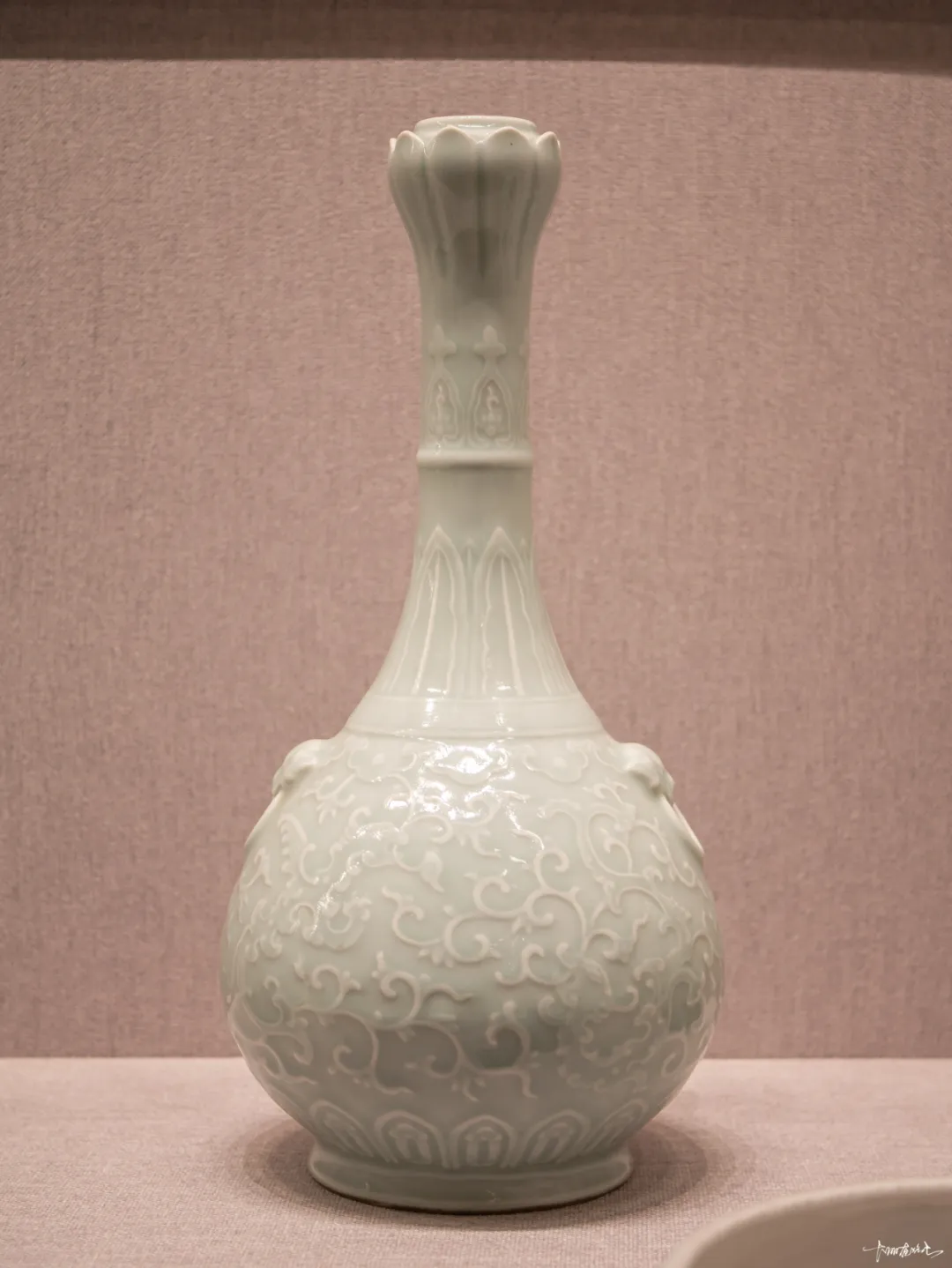

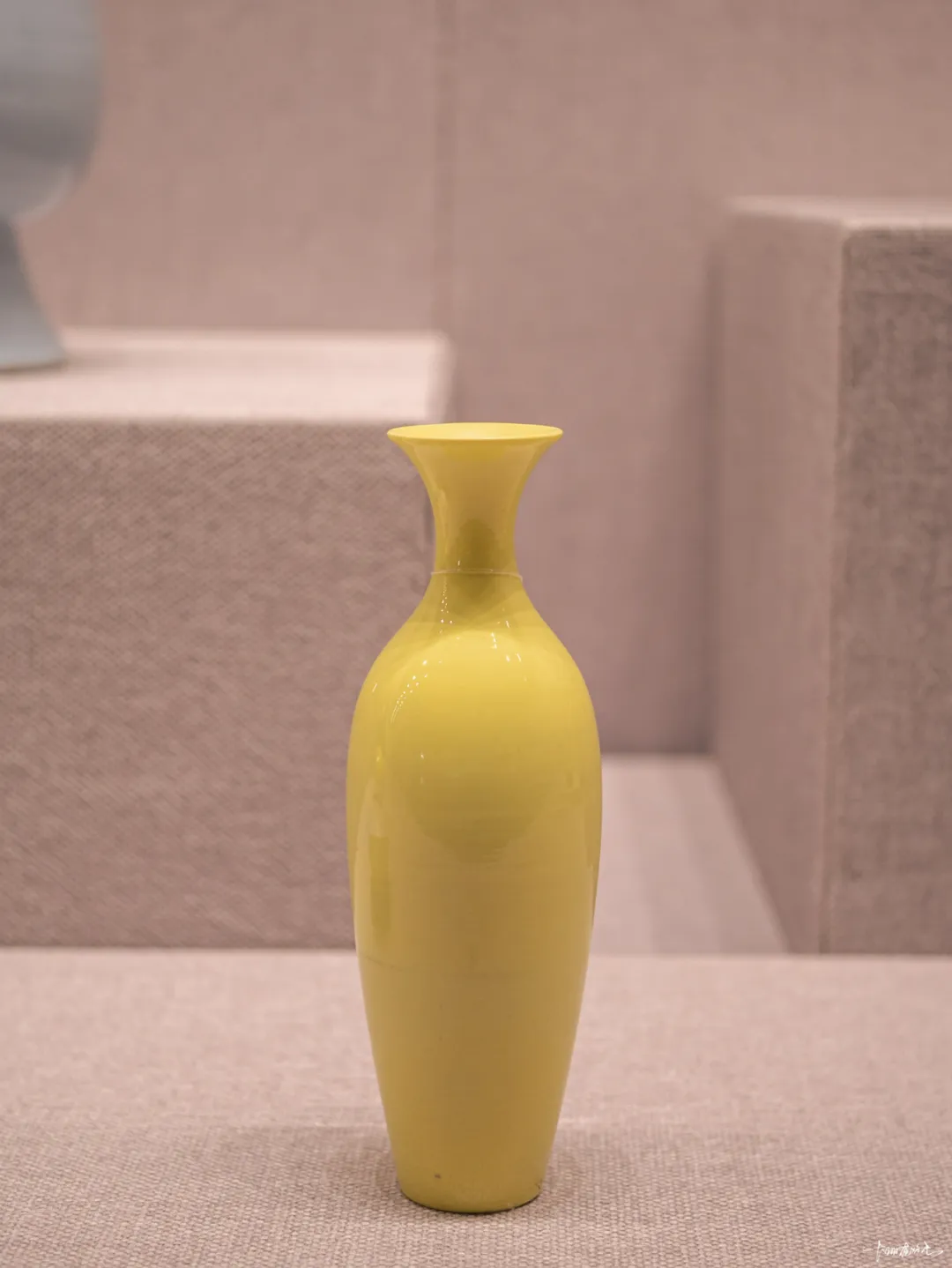

中国是享誉世界的文明古国,在漫长的历史进程中,创造了丰富灿烂的物质和精神文化,陶瓷堪称其中最杰出的代表之一。

故宫博物院是在明、清两代皇宫建筑及其收藏品基础上建立的中国最大的综合类博物馆,在收藏的186万多件文物中,陶瓷类文物约占36万多件,而且绝大部分属于清代宫廷藏品,可谓自成体系,流传有绪。特别是经过几代专家的研究鉴定,使故宫博物院的陶瓷藏品具备较高的真实性和可靠性。

故宫陶瓷馆遴选约一千件具有代表性的陶瓷藏品,从新石器时代磁山文化到民国时期,按时代发展顺序和使用功能分17个单元予以展示,力求反映中国陶瓷约八千年延绵不断的历史和博大精深的文化内涵。

故宫陶瓷馆的展陈是最能展现中国陶瓷史的陶瓷展,展品齐全,按时间线陈列,文字介绍详细,珍贵藏品堆如山,195文物7件,如果时间紧,只逛武英殿即可,这里共10个单元,讲述了从新石器到民国时期中国陶瓷的发展和变化。

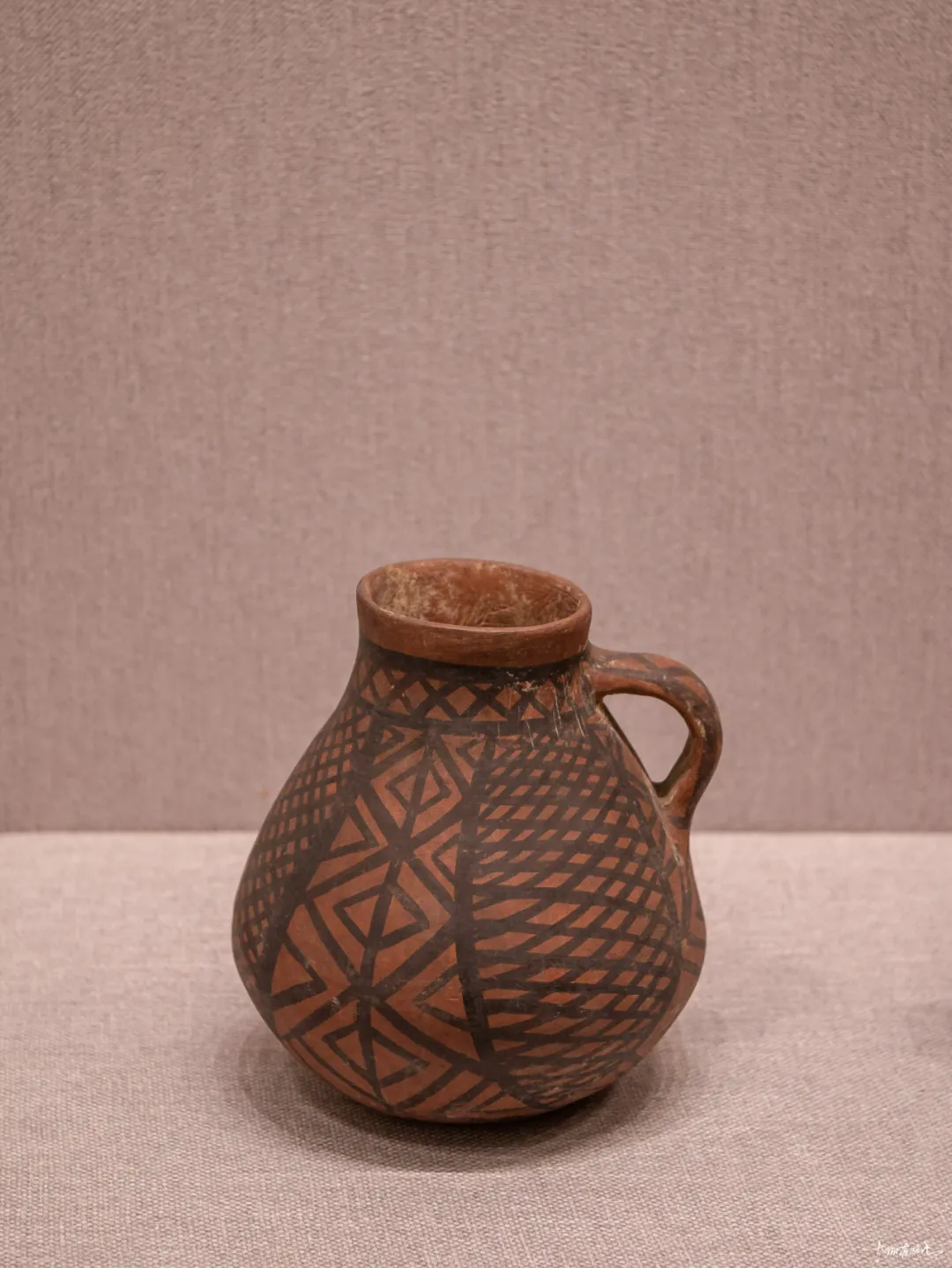

陶器是随着人类对大自然的认识不断提高而产生。考古发现所获得的资料证明,我国的陶器生产距今已有约两万年的历史,陶器是原始先民主要的日常生产和生活用具。

进入新石器时代,制陶术在我国获得很大发展。在黄河流域、长江流域、东南沿海和北方地区的新石器时代文化遗址中,均出土过丰富的实物资料,其中即包括大量陶器。黄河、长江中上游地区以彩陶而闻名,下游地区以工艺精致的白陶和黑陶而著称;东南沿海地区以印纹硬陶为代表;北方地区陶器则以富有民族特色的造型称奇。不同地区出土的陶器各具特色,又相互联系。

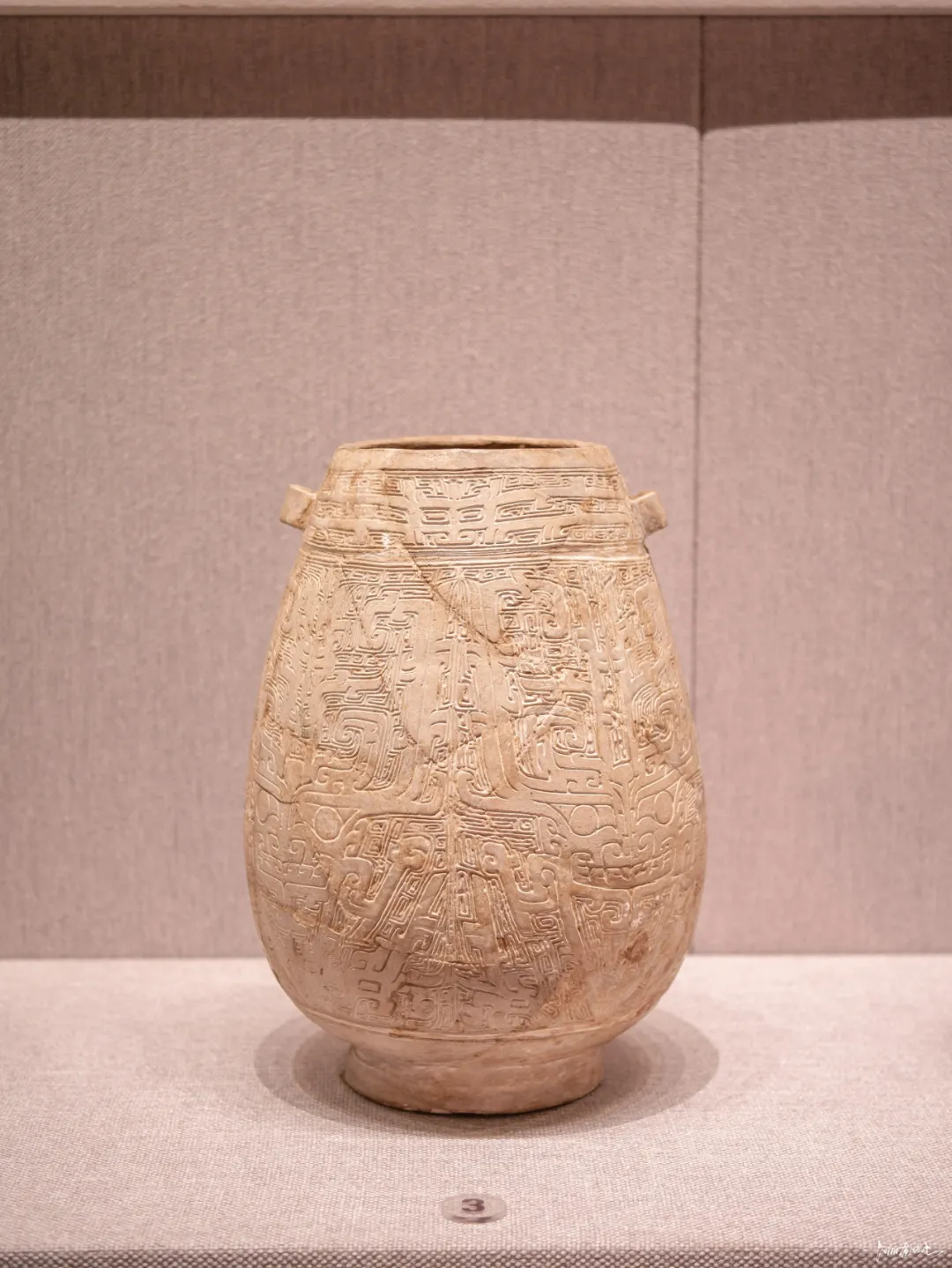

夏、商、周时期,人们主要的日常生活用具仍然是陶器。商代除大量烧造灰陶以外,还烧造精美的刻纹白陶和印纹硬陶。约在夏、商之际出现了原始瓷,为后来成熟瓷器的发明奠定了基础。

战国时期,陶瓷生产更加专业化,印纹硬陶和原始瓷在南方获得普遍发展。秦始皇陵发现的兵马俑,充分体现了秦代高超的制陶水平和精湛的雕塑技艺。

西汉时期,我国北方发明的低温铅釉陶,为后来低温釉彩的发展奠定了工艺基础。东汉时期,成熟瓷器的批量烧造,堪称中国乃至世界陶瓷发展史上的一个重要里程碑,也是中华民族对人类文明做出的杰出贡献之一。

出现于夏、商之际的原始瓷,经过西周、春秋、战国、西汉的发展,至东汉已普遍演进为符合现代标准的成熟瓷器。

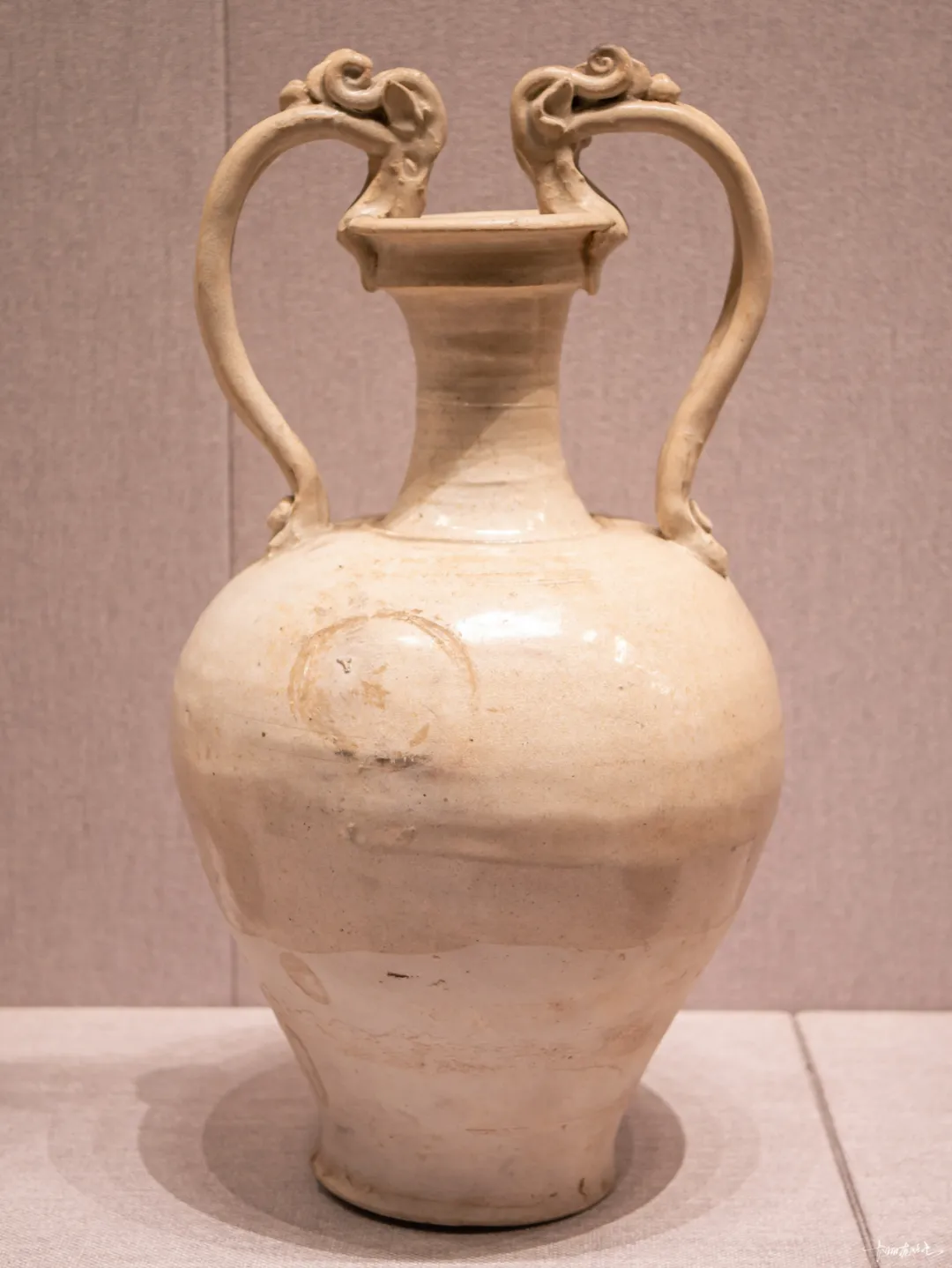

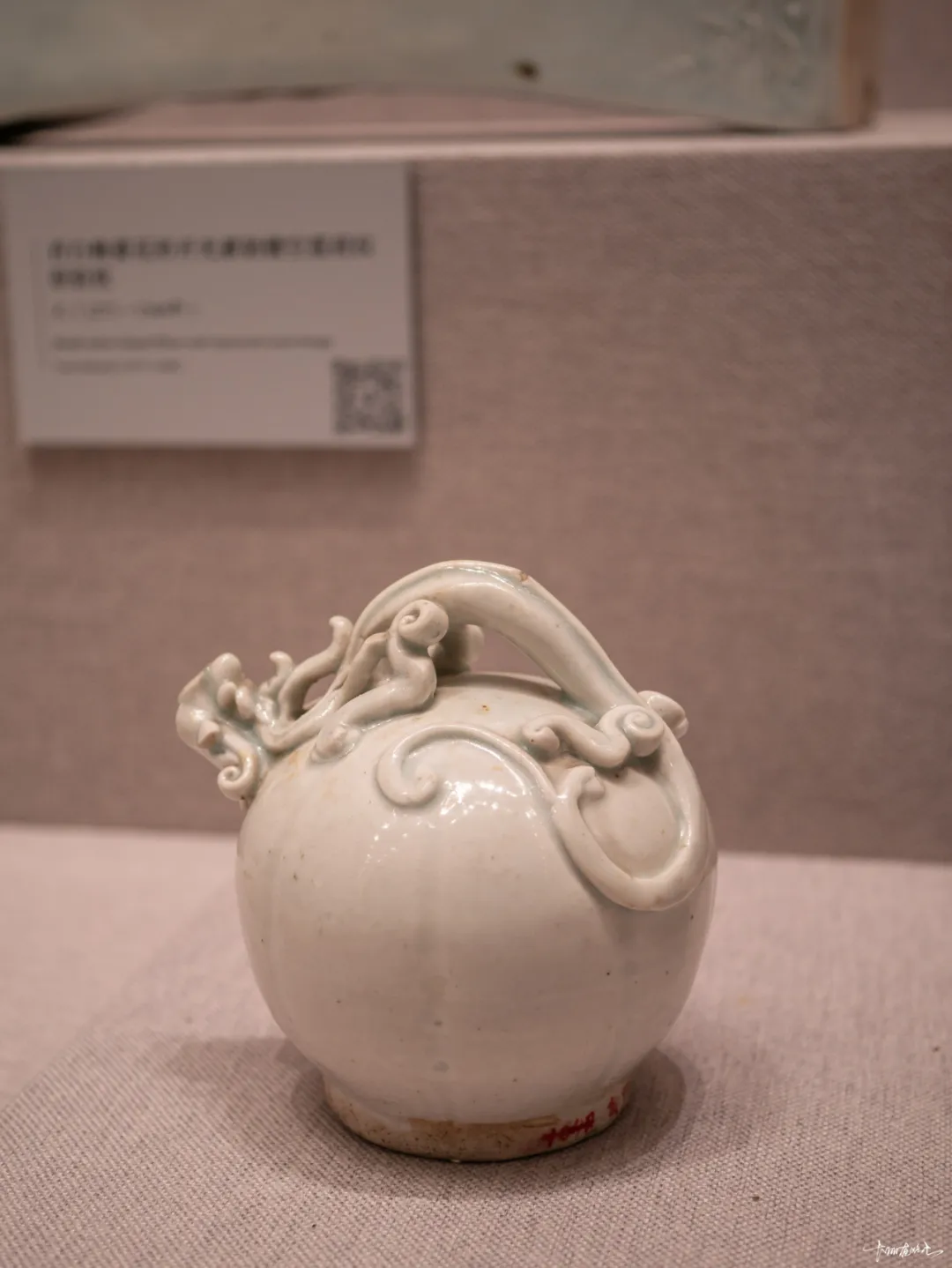

三国、两晋、南北朝历时360余年,陶瓷生产发展迅速,主要表现在南方制瓷技术明显提高,产区和规模不断扩大,江苏、浙江、福建、江西、湖南、湖北、四川等省境内均有窑址分布。瓷器品种主要为青瓷,也有少量黑瓷。器物造型以日常生活和随葬用盘、碗、槅(gé,音:格)、洗、壶、罐、烛台、虎子、唾壶、熏炉、谷仓、人物俑、动物俑等为主,产品各具地方特色。

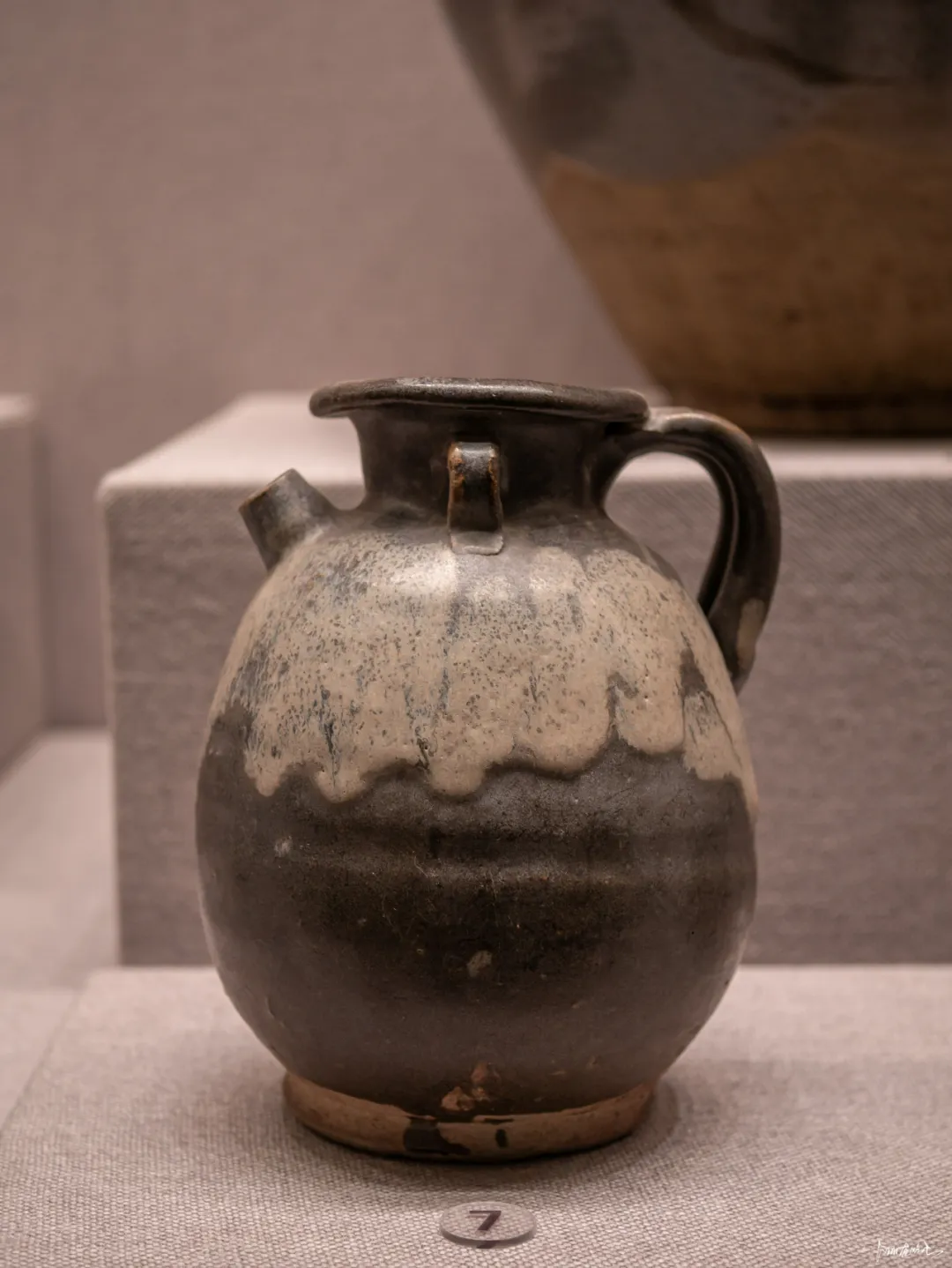

隋代陶瓷生产承前启后,无论在造型还是装饰方面,均呈现出鲜明的时代特点。四系盘口瓶、双联瓶、四系罐、高足盘、鱼篓式罐等,均为隋代瓷器中的典型器物。刻划的忍冬纹、相间排列的模印花朵与花叶纹,均属于隋代瓷器上代表性纹饰。隋代瓷器普遍胎体较厚重,施釉不到底,流釉现象较严重。

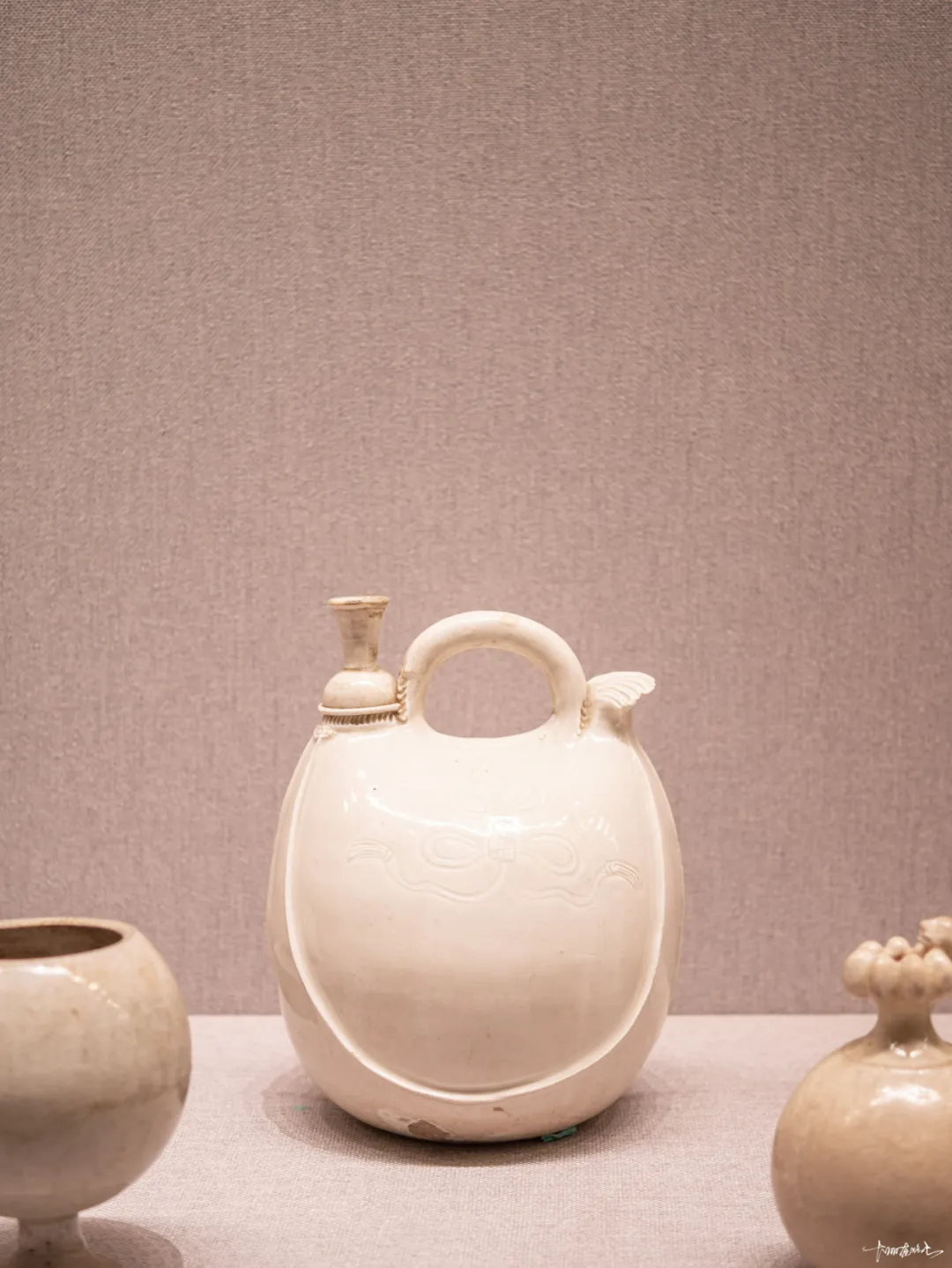

唐代是中国陶瓷生产蓬勃发展时期,瓷窑遍布全国各地,器物造型千姿百态、纹饰丰富优美。陆羽《茶经》提到的当时著名瓷窑就有越州窑、鼎州窑、婺州窑、岳州窑、寿州窑、洪州窑、邢州窑等。饮茶风俗的普及和饮酒风气的盛行,进一步刺激了制瓷业的发展。陶瓷器已成为人们日常饮食、陈设和随葬不可或缺的物品。中外经济、文化的交流和发展,更使中国陶瓷作为特产而开始大量销往亚、非地区,成为中外友好往来的物证。

五代时期的陶瓷继承唐末遗风,不但胎体明显变薄,而且更加注重器物造型的优美和装饰工艺的精细,为宋代陶瓷生产高峰的出现奠定了工艺基础。

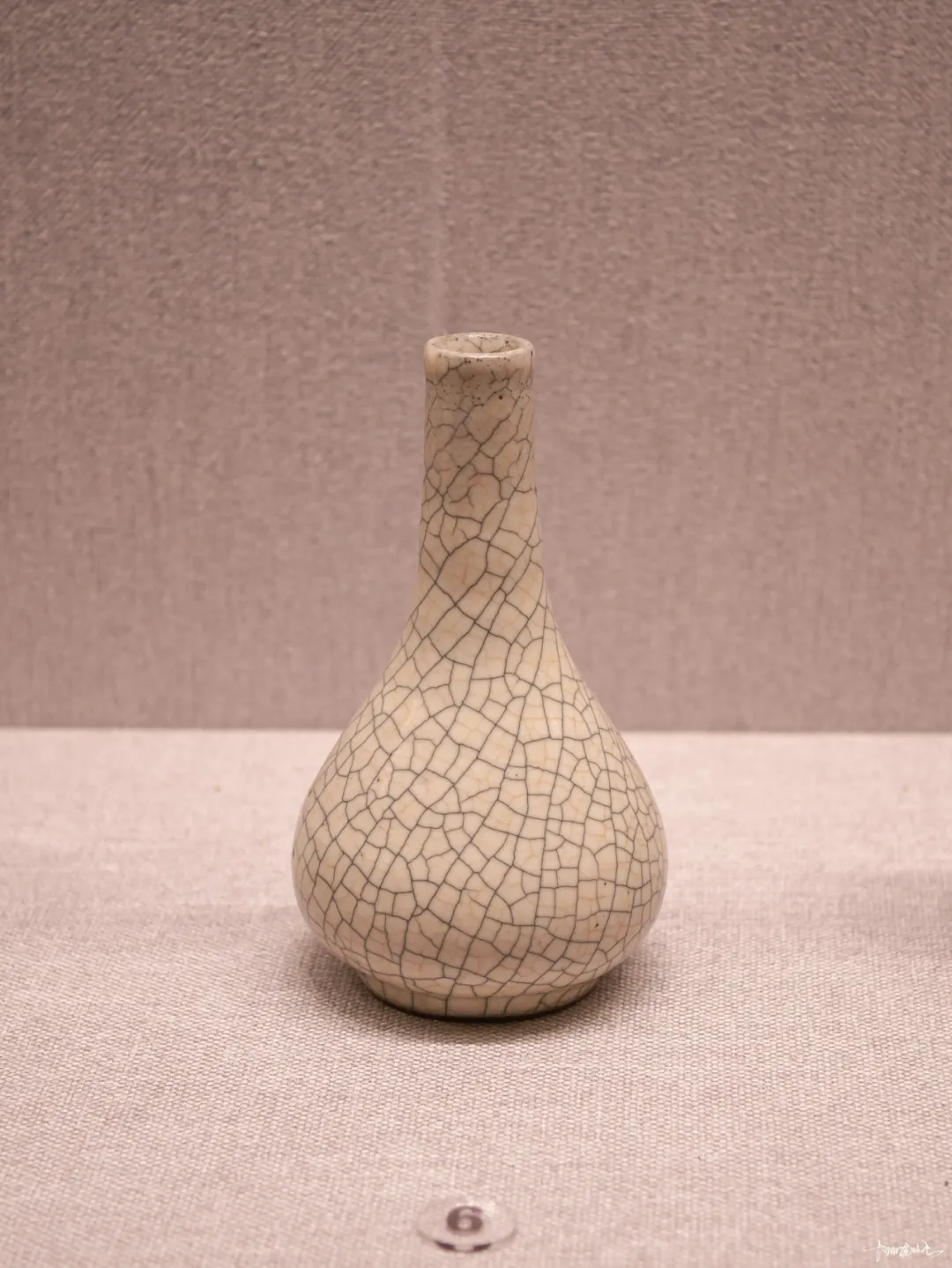

辽、宋、西夏、金时期,陶瓷业蓬勃发展,名窑遍布各地,出现了陶瓷史上前所未有的兴盛局面。在民窑获得发展的基础上,朝廷还在南北方相继设窑专门烧造宫廷用瓷。汝窑、官窑、哥窑、定窑、钧窑、耀州窑、磁州窑、越窑、龙泉窑、景德镇窑、吉州窑、建窑等名窑烧造的瓷器,备受后人推崇。

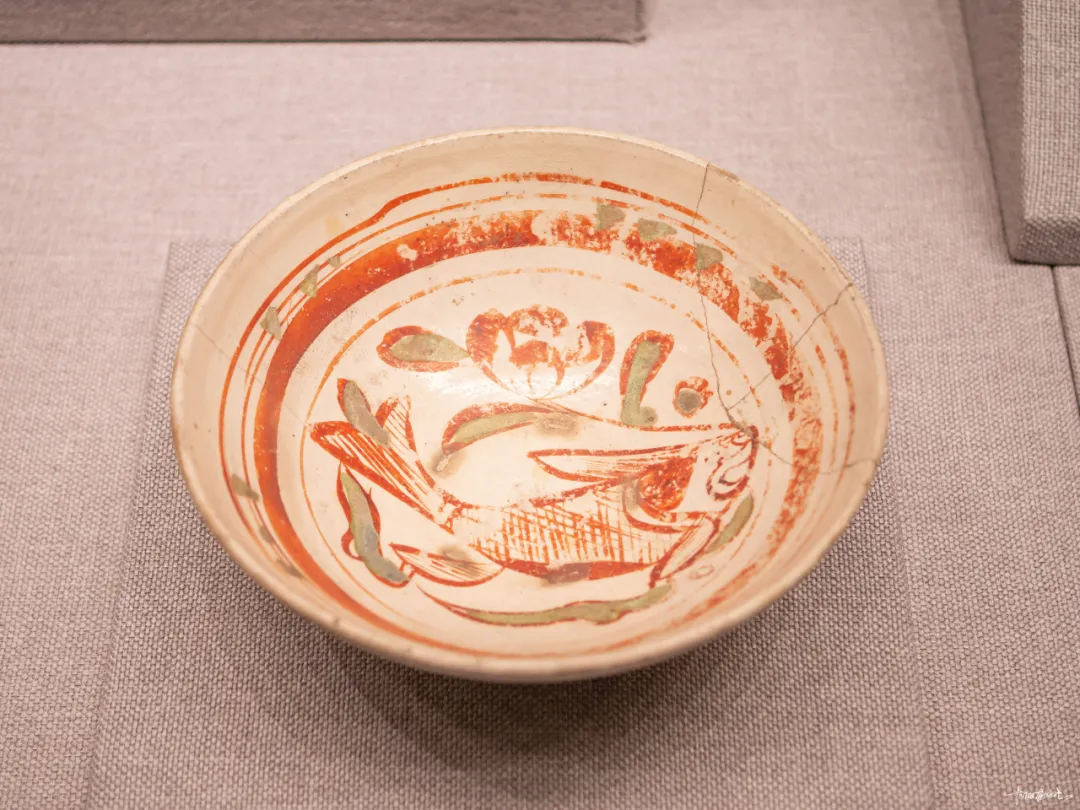

北方地区的辽、西夏陶瓷,既受中原陶瓷工艺影响,又具有民族风格,成为中国陶瓷史上民族大融合的物证之一。女真人灭北宋后,金代制瓷业在北宋基础上继续发展,定窑、钧窑、耀州窑、磁州窑等著名瓷窑,均烧造出具有独特艺术风格的陶瓷。

这一时期南北各地还形成一些工艺技法、装饰风格相似的瓷窑体系,如北方地区的定窑系、钧窑系、耀州窑系、磁州窑系等,南方地区的越窑系、龙泉窑系、建窑系、景德镇窑系等,有的窑系还延续到元代。

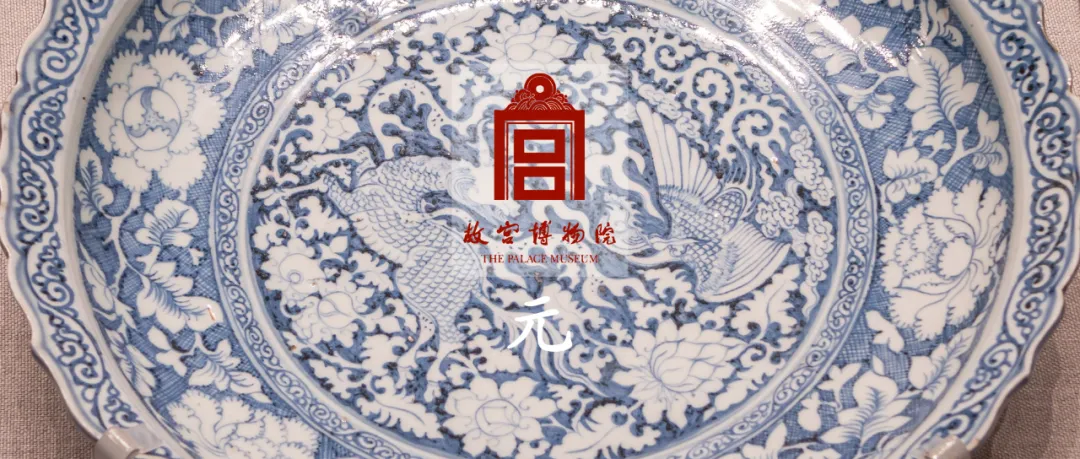

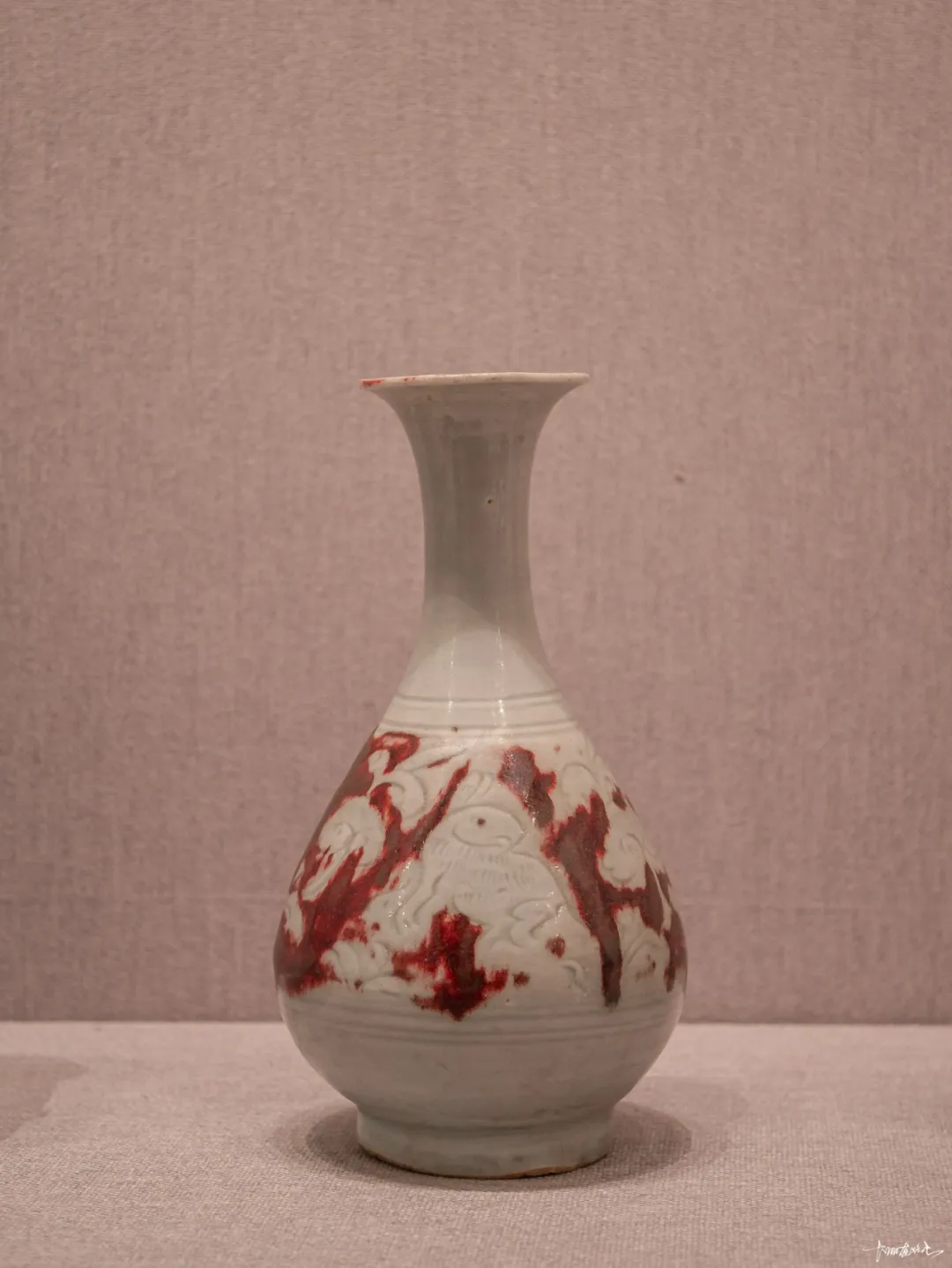

1279年,元王朝统一中国。位于今江西省东北部的景德镇,得天时、地利、人和之便,异军突起,既继承又创新,烧造出青花、釉里红、卵白釉、蓝釉瓷等新品种,遂使景德镇一举成为全国最重要的瓷器产地之一,为明、清两代进而成为全国的制瓷中心奠定了基础。钧窑、磁州窑、龙泉窑、德化窑等继续烧造传统陶瓷品种。

海外贸易的蓬勃发展,促使陶瓷生产呈现兴盛局面。元代陶瓷不但畅销国内,而且远销海外,亚洲、非洲沿海地区均曾出土过元代景德镇窑、龙泉窑和福建、广东窑场烧造的陶瓷器。

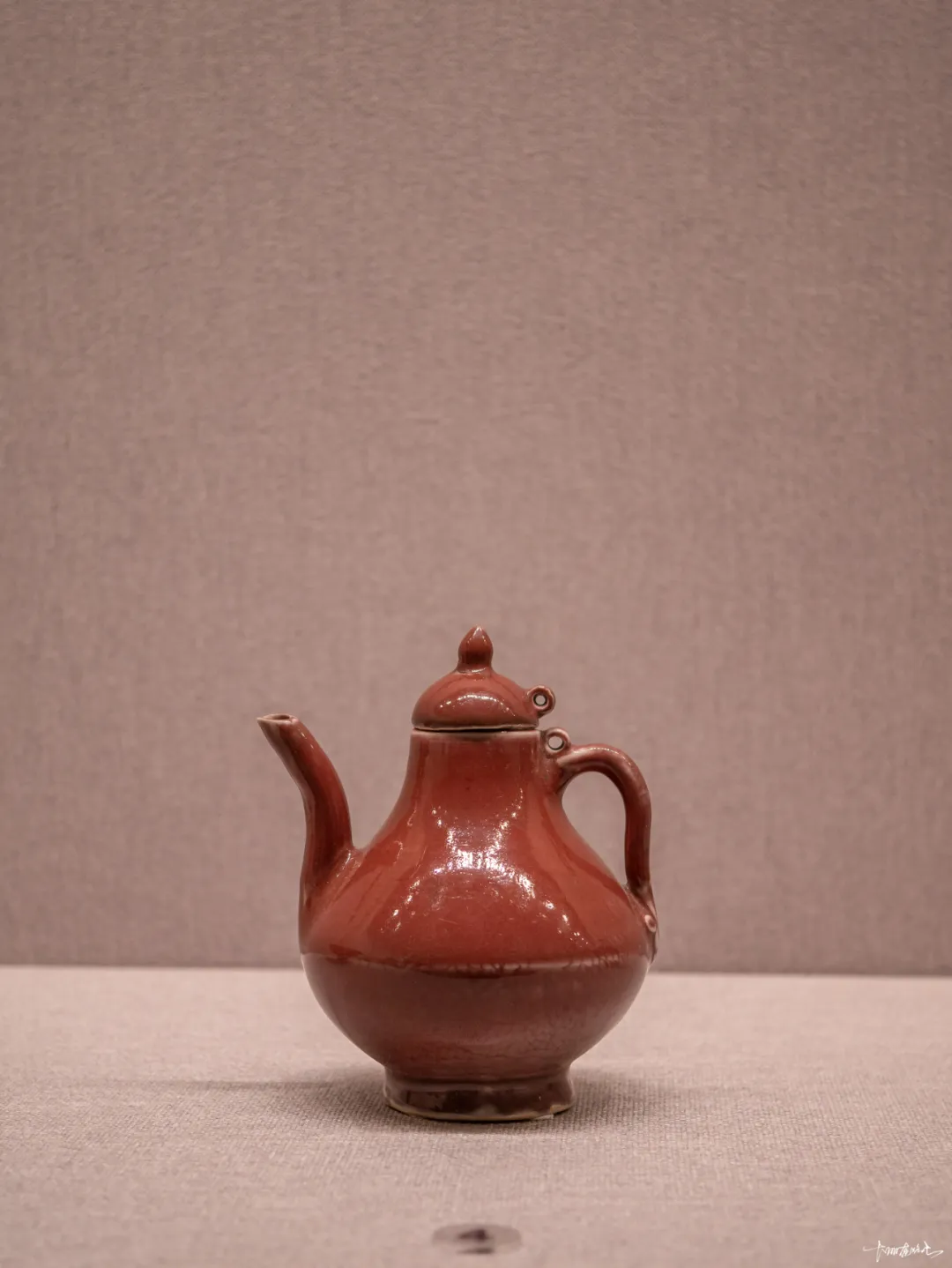

明代景德镇窑分为御窑和民窑两种。洪武二年(1369年)朝廷在景德镇设“陶厂”,建文四年(1402年)更名为“御器厂”,专门烧造宫廷用瓷。此后,历朝沿袭这种制度,源源不断地为宫廷烧造了大量至精至美、品种丰富的瓷器,直至万历三十五年(1607年)停烧。御窑的发展带动了民窑的逐渐兴盛,至明代晚期,景德镇从事瓷器生产的工匠已达十余万人,遂成为全国的制瓷中心、世界的瓷都。永乐、宣德、成化三朝的青花瓷,永乐、宣德朝的鲜红釉、祭蓝釉、甜白釉瓷,成化朝的斗彩瓷,弘治朝的浇黄釉瓷,嘉靖朝的瓜皮绿釉瓷,万历朝的淡茄皮紫釉瓷,嘉靖、隆庆、万历朝的五彩瓷等,均为明代瓷器中的著名品种,堪称中国乃至世界陶瓷史上永恒的经典之作,备受后人推崇。

△此罐是明嘉靖官窑青花五彩瓷器中的名品,形体高大规整,胎体厚重,色彩艳丽,构图疏密有致。所绘鲤鱼鳞鳍清晰,与周围的莲花、浮萍、水草融合在一起,显得生动逼真。

明末清初,随着农民起义愈演愈烈,明王朝最终走向灭亡,清朝入主中原坐稳江山,中国社会发生剧烈变革。从明代万历三十五年(1607年)到清代康熙二十年(1681年)的70多年时间里,作为全国制瓷中心的景德镇,其瓷器制造业也经历了一次重大转变。主要表现是,万历三十五年以前的制瓷业是以御窑占统治地位,此后,御窑生产急剧衰落,民营瓷业则因国内和亚欧市场需求的刺激而渐趋兴盛,跃居主导地位。人们习惯于将景德镇制瓷业在17世纪发生变化的这一时期称作“转变期”或“转型期”。

清代景德镇窑仍有御窑和民窑之分。清代统治者革除了明代在手工业方面的一些弊病,废除明代御器厂实行的编役制,将明代晚期出现的“官搭民烧”作为定制,刺激了官民竞争,促进了民营瓷业进一步发展。

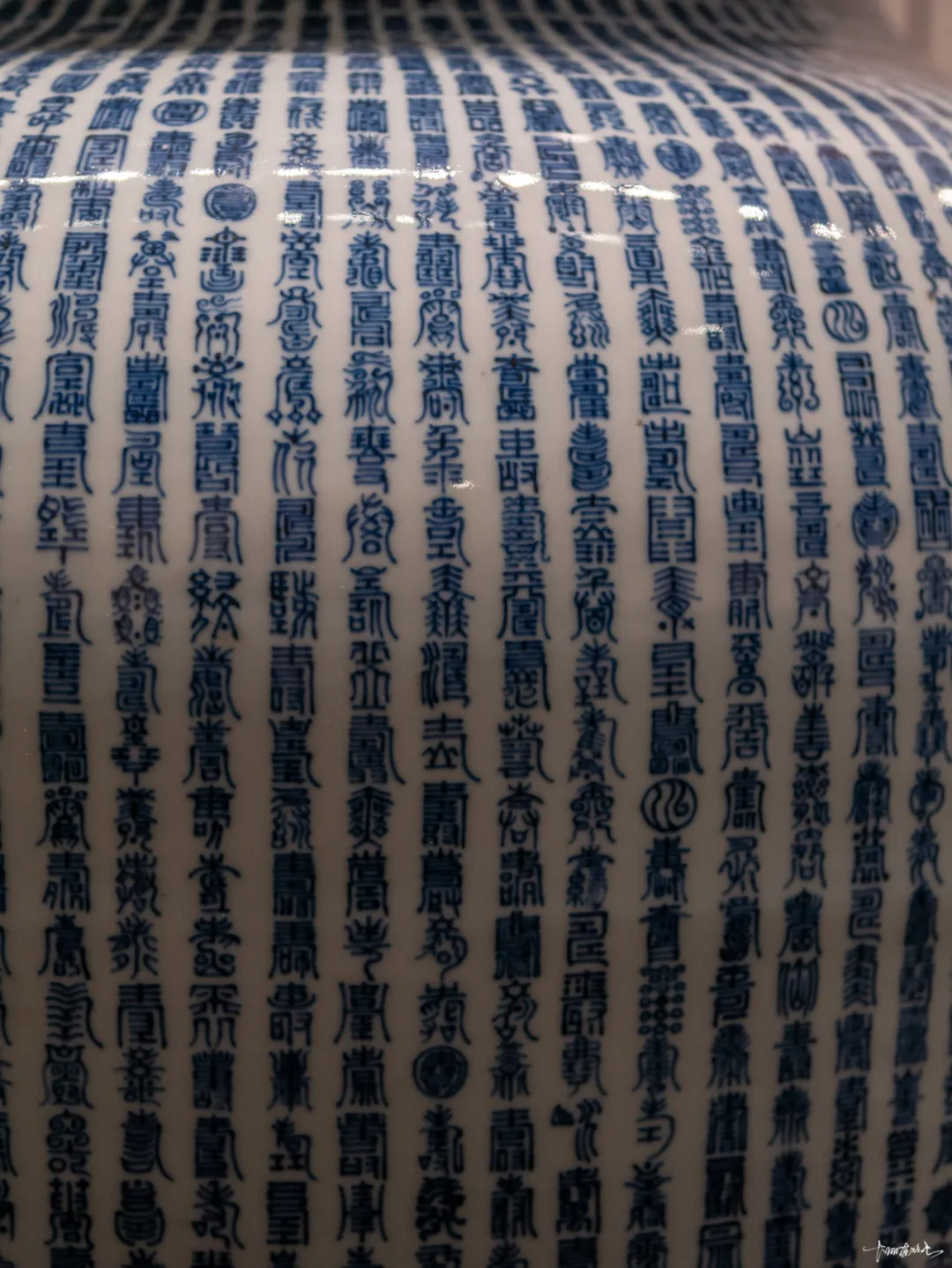

据文献记载,清代景德镇御窑更名“御窑厂”。随着康熙、雍正、乾隆三朝盛世的到来,景德镇陶瓷烧造也达到鼎盛。由于这三朝皇帝均对瓷器烧造表现出浓厚兴趣,加之督陶官苦心勠力经营,遂使景德镇御窑在仿古的基础上,又创烧出大量新品种。雍正十三年(1735年)唐英《陶成纪事》罗列当时仿古和创新的瓷器多达57个品种。德化窑、石湾窑和宜兴窑等地方窑场也沿袭明代风格,继续烧造传统品种的陶瓷。

从烧造工艺上看,青花与仿官釉、仿汝釉、仿哥釉、窑变釉、粉青釉、霁蓝釉等均属高温釉、彩,需先焙烧。而粉彩、珐琅彩、金彩及松石绿釉等均属低温釉彩,需后焙烧。如此复杂的工艺只有在全面掌握各种釉、彩性能的情况下才能顺利完成。

清代乾隆时期历时六十年,是封建社会发展的太平盛世。此时,由于乾隆皇帝嗜古成癖,对瓷器情有所钟,再加之督陶官唐英对景德镇御窑厂的苦心经营,一大批身怀绝技的名工巧匠汇集于景德镇,致使御窑厂的瓷器生产无论在数量还是质量上都达到前所未有的境界。特别是各种新奇淫巧的制品层出不穷,其工艺技术之高可谓鬼斧神工。这件各种釉彩大瓶,集各种高温、低温釉、彩于一身,素有“瓷母”之美称,集中体现了当时高超的制瓷技艺,传世仅此一件,弥足珍贵。

清代道光二十年(1840年)鸦片战争以后,随着内忧外患接踵而至,清王朝日趋衰败,景德镇制瓷业总体上呈现逐渐衰退的局面。但清代晚期御窑瓷器仍然有闪光点,例如专为同治皇帝大婚和慈禧皇太后万寿批量烧造的成套用瓷,有如天边一抹晚霞,闪耀余辉。

文字参阅故宫博物院官网/故宫博物院文物铭牌

一个人喝葡萄酒,往往始于法国,却止于意大利。对于这句话,很多对意大利葡萄酒缺乏了解的爱好者或消费者表示不理解。

大多数的时候,对事物的误解和偏见,往往是因为对这件事物缺乏了解。而意大利葡萄酒虽然很强大,却因为体系复杂,又得不到教育和利益系统的支持,成为了中国葡萄酒市场中不被大多数爱好者和消费者了解的神一般的存在。

这话有两层含义,第一层是大家最开始喝的都是法国酒,意大利一般都是后来才接触;第二层是葡萄酒喝的多了,时间久了,对葡萄酒的了解越来越多,如果接触到意大利酒,很可能成为意大利葡萄酒的忠实爱好者。

由于做意大利葡萄酒媒体的缘故,在我的身边,有越来越多意大利葡萄酒的忠实粉丝,只有见到这些人,深入的了解他们,你才能理解这句话语的意思。

我所见到的意大利葡萄酒爱好者,他们是有共性的,热爱生活,爱学习,有热情,逻辑思考能力强。他们的葡萄酒知识和经验普遍都比较深厚,对全球主要的葡萄酒产区和知名酒庄,都有比较充分的了解。

因为他们对葡萄酒的了解大多是从法国开始的,新世界的酒也喝了很多,所以他们能够客观的认识全球葡萄酒体系,对意大利葡萄酒的优势和特点,有着清晰的认识。

前些天曾有朋友在酒窝微信群里组织法国酒与意大利葡萄酒的辩论,结果居然找不到法国酒的辩方代表,最后变成了意大利葡萄酒爱好者的分享课。当然,组织者还在进行后续的组织和招募,期望能够促成一场精彩的法国酒与意大利酒之间的辩论赛。

我很期望这场辩论赛能够组织起来,如果专业的法国酒爱好者和意大利酒爱好者能有一场精彩的辩论,对于所有的葡萄酒爱好者和消费者而言,都是一件很有意思的事情,也能有效的传播和普及相关的葡萄酒知识。

然而从当下的情况来看,组织这场辩论赛最大的问题是,你很容易就能找到很多位非常熟悉和了解法国的意大利葡萄酒忠实爱好者,但是却很难找到了解意大利的法国葡萄酒的忠实爱好者,这就出现了辩论赛选手知识不对等的问题。

意大利酒爱好者的辩方代表会有一种无奈,我完全了解你,你却对我知之甚少,咱俩怎么辩~~??这就像一场战争,一方对另一方的情报了如指掌,没有情报的一方是不可能赢得这场战争的。

有没有特别深入了解意大利,又不喜欢意大利而专爱法国酒的专业人士呢?目前还没有人站出来要参与辩论,如果有,这场精彩的辩论赛很快就可以组织起来了。

在法国酒和意大利酒之间,其实本不必去制造这种冲突,在多姿多彩的葡萄酒世界里,每个国家、产区和葡萄品种,都有其独特的个性和魅力存在着。只要是好喝的葡萄酒,来自哪里并不重要,旧世界和新世界,都有着各自的精彩。

因为只有了解更多,才能更客观的看待问题。我尽可能从客观的角度,来分析一下开始那句话的两层意思。

为什么大家最开始喝的都是法国酒,后来才是意大利?

我给大家解释意大利葡萄酒的时候,通常会给大家一个我自己创造的概念。我通常会说:“在我的葡萄酒世界里,我把葡萄酒生产国分为:意大利,和其他国家。” 为什么这么分?因为除了意大利之外,全球主要的葡萄酒生产国,其实都是主要使用法国葡萄酿造葡萄酒,所以这些在全球普及的法国葡萄(赤霞珠、品丽珠、美乐、黑皮诺、长相思、霞多丽、雷司令等),通常被意大利人称为国际品种。虽然葡萄酒是伴随着罗马皇帝的征服在欧洲开枝散叶的,但是法国在近现代葡萄酒产业的发展中,的确是居功至伟。

所以在大多数时候,酒商和消费者其实只要了解不到10个葡萄品种,就可以很容易的深入到除了意大利之外的主要产酒国(法国、智利、澳大利亚、美国、南非、西班牙,乃至中国)。但是如果你要了解意大利,你会发现你所熟悉的10种葡萄,虽然在意大利也有种植,但是更精彩的是,这里还有400多种你完全不了解的意大利本土品种。

不要说酒商,就是很多专业人士,因为在学习和工作中接触的,主要是以法国葡萄和普通酿造工艺为核心的知识体系,毕竟全球除了意大利之外,主要的葡萄酒生产国都是遵循法国葡萄酒的酿酒哲学和逻辑在发展的。即使掌握了非常丰富的法国葡萄酒知识,获得了非常专业葡萄酒教育(比如WSET三级以上)认证的专业人士,却往往对意大利葡萄酒知之甚少。

所以我认为,意大利葡萄酒具有最大的多样性和复杂度,却没有能在中国普及的知识教育来支持,这可能是意大利葡萄酒进入市场较晚的主要原因。

当然,法国葡萄酒企业进入中国比较早,这中间有法国人的商业头脑因素,毕竟很多法国名庄的老板,大多是法国知名大集团和大富豪,他们对中国葡萄酒市场的启蒙和教育,做出了很多贡献。

有意思的是,从品牌传播的角度而言,法国葡萄酒得以在中国建立较高的知名度,更要感谢的是张裕、长城在多年以前不遗余力的,数以亿计人民币投入的广告和宣传,主题是描述山东和河北产区与波尔多同纬度,所以也能生产高品质的葡萄酒,在中国人心目中将波尔多塑造成葡萄酒的唯一圣殿,虽然事实并非如此。

起到助推作用的,当然还有二三十年前,香港电影中黑社会老大、赌神,或者富豪对拉菲葡萄酒的推崇。要知道,那个人民群众文化生活比较贫瘠的时代,很多香港电影的观看率,都是10亿以上的。如此看来,任何事情的成功,都不是偶然,但是影响成功的因素,往往和这件事物有着微妙的联系。

如今意大利葡萄酒在中国的市场份额只有5.5%,排在法国、澳大利亚、智利、西班牙之后。所以我经常会遇到这样的问题,意大利酒是不是不行呀?

真正的事实是,意大利目前是全球最大的葡萄酒生产国,在美国、德国、英国这样的成熟市场,意大利葡萄酒的市场份额都是第一。

中国是全球第二大葡萄酒市场,却是意大利排名第13的出口目的国,中国市场意大利葡萄酒的进口额,不到意大利葡萄酒出口总额的1/50。所以这真的不是意大利葡萄酒行不行的问题,而是中国市场为什么和成熟市场不同的问题!

没有哪个国家有中国这么大的VCE葡萄酒进口量,每年的进口瓶数数以亿计。法国一些灌瓶厂把来自全欧洲的散装原酒,用工业化的方法加工成Made in France的欧洲餐酒,倾销的到中国。奇怪的是,我只见到法国南部的酒农很愤怒,但是却很少见到中国酒商因此感到惭愧和气愤,甚至质疑这种产品的品质都成了一件很容易得罪人,甚至被攻击的事情。

更可悲的是,由于需求太大,来自法国的VCE居然出现了供不应求的趋势,价格开始上涨,于是来自其他国家的类似产品也开始涌现。

二十年来,大家都觉得葡萄酒市场的春天要来,但是一直没来。你们觉得原因是什么?VCE们真的是可以让消费者有好的体验?感受到愉悦?产生消费粘性和重复购买吗?那些酒商自己都不敢经常喝的酒,消费者能侥幸多活几年都是奇迹,真的会喝出忠诚度,能培育出一个健康的葡萄酒市场来吗?

其实这真的不能只怪法国酒,也不能怪法国人。说到这里,我要说的是,法国有很多品质优良的葡萄酒,智利、澳大利亚、美国、南非,还有中国,都有很多质量很好,价格合理的葡萄酒。我们中国消费者,真的应该多享受那些物美价优的葡萄酒。

言归正传。

为什么葡萄酒喝的多了,时间久了,对葡萄酒的了解越来越多,如果接触到意大利酒,很可能成为意大利葡萄酒的忠实爱好者?

对于大多数葡萄酒爱好者而言,葡萄酒的丰富、多变和不可掌控,是吸引很多人去不断探索的主要原因。熟悉了法国葡萄酒,喝了名庄,喝遍了新世界,意大利将是一座不可绕过的山脉。

对于大多数葡萄酒爱好者而言,意大利葡萄酒是未知、神秘和不容易亲近的。了解意大利,要放空自己,用更开放的心态去尝试和了解。这个开始的过程,最好有一位了解意大利葡萄酒的朋友做引导,不然很多人可能是因为不了解和误会,错过那扇刚刚打开的意大利葡萄酒之门。

我经常对刚刚开始接触意大利葡萄酒的朋友说,了解意大利,不能按照理解法国酒的方式,因为意大利的葡萄种植和酿酒的哲学与逻辑,与以法国为代表的葡萄酒世界不同。

法国有代表性的三个产区,波尔多、香槟和勃艮第。尊重风土,但是采取了非常多的人工干预,不仅仅在葡萄种植的环境,尤其是酿造中,小橡木桶的使用、瓶中二次发酵中酵母的使用,都是通过人工去弥补葡萄风土的不足,或是赋予本不属于葡萄的一些更完美的元素。

我发自内心的注重法国对于葡萄酒产业发展的巨大贡献,也非常享受那些近乎完美的法国精品酒的品质,这种哲学和技术也因此在全球被广泛的使用,带给全球消费者美好的体验。

那意大利和法国的不同是什么呢?

是意大利葡萄酒的多样性,最少的人工干预以实现对风土的保护和尊重,以及追求个性和创新精神。

我经常用这样的一个比喻,来对比法国为代表的葡萄酒和意大利葡萄酒。

我说,法国葡萄酒所代表的风格,就像你去参加一个隆重的晚宴,你走进房间,所有的男士都是身着燕尾服的绅士和贵族,所有的女士都是盛装晚礼服的淑女和贵妇,彬彬有礼,温文尔雅。

然而意大利,却是同样的一个晚宴,你走进去,发现里面容纳了各种个样的人,有政要、有商人,有艺术家、也有科学家,有明星、也有贵族,有赛车手、也有足球运动员,有工程师、也有it男,有玩美术的、也有玩音乐的。

即使是玩音乐的,有搞交响乐的、有唱歌剧的,有搞古典的,也有玩现代的。即使是摇滚乐,也有乡村、布鲁斯、迷幻和重金属。这就是意大利,风格各异,多姿多彩,即传承经典,也乐于创新;即尊重市场,也坚持个性。

说到这里,你能理解为什么那么多人深爱意大利吗?

或许是因为尊重,或许是因为你可以有更多的选择,或许是因为没有人要求你必须记住这个酒是否是名庄,是不是很贵。在意大利只要你愿意探索,总有一种或几种价格不贵的意大利酒,能让你刻骨铭心,痴心不改。

我有一个发现,很多人问我,意大利为什么没有排名,没有列级庄?

我说,意大利从政府到产区,没有人愿意去排名,或许是他们期望更多的公平,或许是不去制造利益集团。

在法国波尔多,为什么很少有酒庄能超越1855列级庄?

评级,是奖励优秀者。但是评级也是一把双刃剑,因为列级庄可能会变成利益集团,变成产区的天花板。智利十八罗汉,谁想称为第十九罗汉?那要先经过18位利益获得者的同意,这就是江湖,放之四海皆准…

我采访过很多意大利葡萄酒产区,大多数人都认为排名只能代表过去,不能激励一家酒庄把酒酿的更好。他们认为,每个酒庄主和酿酒师都有权利去追求自己认为好的风格和个性,一个值得大家学习的榜样,不应该是怎么把葡萄酒做成一个样子,而是制造出更多不同的美好!

这就是我眼中的意大利葡萄酒,或许是因为喜爱,有些许的不够客观。但是,如果这篇文章能唤起你尝试和了解意大利葡萄酒的兴趣,我想,我们的葡萄酒世界将会更加丰富多彩,我们也将得到更多不同体验带来的快乐。(Quelle:https://m.winesinfo.com/ 略有删节)

Amphitrite, femme de Poséidon dans la mythologie grecque, est également le nom du premier vaisseau français à accoster sur les côtes chinoises. Après les Portugais, les Hollandais et les Anglais, la France entreprend, grâce à ce navire, le commerce direct avec La Chine. Au tournant du XVIIIe siècle, le vaisseau réalise ainsi deux expéditions.

Genèse du premier voyage de l’Amphitrite

L’histoire de ce vaisseau débute bien avant son départ pour Canton le 6 mars 1698 car le projet de cette expédition naît à Pékin et non en France. Lors de l’ambassade française au Siam en 1685, le vaisseau l’Oiseau embarque à son bord six jésuites qui doivent rallier la capitale impériale. Parmi eux figurent le père Joachim Bouvet (1656-1730) et le père Jean de Fontaney (1643-1710) . Après quelques années, l’empereur chinois Kangxi (1654-1722), avide de savoirs occidentaux, mandate le père Joachim Bouvet afin de ramener en Chine de nouveaux missionnaires français. Désigné « envoyé spécial de l’Empereur », le père Joachim Bouvet rentre en France en mars 1697.

Histoire de l’armement

En avril 1687, le père est reçu par Louis XIV qui n’est pas très enthousiaste dans un premier temps par ce voyage mais il se laisse convaincre car l’expédition représenterait une aide conséquente à la conversion de l’empire chinois. Néanmoins, le père jésuite ne parvient pas à obtenir le titre de vaisseau du roi. Après avoir contacté la Compagnie des Indes françaises qui se montre réticente à cette entreprise qu’elle juge audacieuse et risquée, le père Bouvet se tourne vers Jourdan de Groussey, responsable des ventes de la manufacture des glaces. Via le comte de Pontchartrin, le vaisseau l’Amphitrite de 500 tonneaux est acheté puis rapidement chargé de quantité de glaces, de marqueterie française, de portraits de la cour, de pendules, de montres et de liqueurs. Le récit de voyage de Froger, matelot sur le vaisseau, est très instructif sur la cargaison et sur leur finalité. Il fournit également de nombreux détails sur la route empruntée et la direction des vents. Celui du peintre italien Gio Ghirardini est plus pittoresque que le récit de Froger de la Rigaudière car il relate son expérience personnelle. En raison du manque de sources manuscrites sur le premier envoi, lacune qui est remarquée par Paul Pelliot, les récits de voyage constituent les premiers documents mobilisables pour connaître les détails de l’expédition.

De son départ de la Rochelle le 6 mars 1698 jusqu’à Canton le 2 novembre 1698, le voyage se déroule sans embûche même si l’équipage manque le détroit de la Sonde. Une fois arrivé à Canton, le statut du navire pose problème. Si Louis XIV n’a pas autorisé le titre de vaisseau du roi à l’Amphitrite, afin de ne pas froisser les Portugais, le père Joachim Bouvet affirme pourtant bien le contraire au capitaine de La Roque. Néanmoins, l’ambivalence de statut du navire, vaisseau marchand ou vaisseau de tribut, entraîne nombre de complications au sujet de la cargaison et des taxes à acquitter. Le vaisseau est finalement exempté de toutes les taxes marchandes et les biens destinés à la cour sont bien acheminés jusqu’à Pékin. Déchargement puis chargement ont entraîné de nombreux retard et l’Amphitrite ne repart de Canton que quatorze mois plus tard, le 26 janvier 1700.

Retour et second voyage

Le retour du vaisseau à Lorient le 3 août 1700 et la vente des produits chinois à Nantes est à la hauteur des ambitions placées dans l’expédition. La soie est autorisée à être écoulée en France tandis que les porcelaines des 181 caisses de la cargaison de retour se vendent très bien et font sensation en France. A partir de ce premier voyage, l’Amphitrite est armé une deuxième fois le 7 mars 1701 pour la même destination. Si le premier voyage ne fut qu’une tentative en vue d’établir des connaissances plus précises sur les biens commercialisables en Chine, les informations rapportées ont été très instructives pour le second envoi et rendent les deux expéditions indissociables l’une de l’autre. Elles ont également de grandes similitudes telles que l’établissement du commerce français dans cette région, la mise en place de deux ambassades officieuses, et le rôle des jésuites comme intermédiaires culturels. Sur ce point, le père Jean de Fontaney est au second voyage de l’Amphitrite ce que le père Bouvet fut pour le premier. Il rentre en France au terme du premier voyage du vaisseau et contribue à la mise en place de la seconde expédition. Savary des Bruslons, dans Le Dictionnaire universel du commerce, détaille par ailleurs la cargaison aller pour ce deuxième voyage. Cependant, le second voyage connaît de plus grandes difficultés (exemption refusée, démâtage, perte de l’ancre et de nombreux morts). Il laisse plus de 100 000 livres de pertes et représente ainsi une grande déception sur le plan commercial.

Considéré par Paul Pelliot comme le point de départ des relations franco-chinoises, l’Amphitrite ouvre la voie a plusieurs dizaines de vaisseaux français tout le long du XVIIIe siècle.

Légende de l'image : Le voyage en Chine : esquisse de décor de l'acte III : le bateau à vapeur " la pintade". P. Chaperon

Here the artist William Alexander represents the moment when Lord Macartney, a British diplomat, was received by the Qing Emperor Ch’ien-Lung on the occasion of the first embassy to China. Within the grounds of the imperial palace at Jehol (Chengde), a lavish tent was erected to host the audience on 14 September 1793. Despite the level of detail in this sketch, Alexander, official draughtsman to the Embassy, was not actually present to witness the event. His reconstruction is based on verbal accounts and sketches produced by core members of the delegation. Those twelve members are depicted at right, each man numbered to correspond to a labelled key at top right. Sir George Staunton, the Secretary to the Embassy and East India Company official, stands behind Macartney, wearing the silk robes and velvet hat which mark him as Doctor of Laws from Oxford University. Other members of the retinue include Lieutenant Henry Parish, whose sketches of the Embassy provided the absent Alexander with important source material.

Surrounded by courtiers, Ch’ien-Lung is depicted seated at his throne with Macartney before him. The Ambassador, on the orders of his British advisors, decided to forgo performing the customary ritual of the kowtow before the Emperor. This required an individual to kneel with both knees on the ground and prostrate themselves low enough so that their forehead touched the ground. The kowtow was considered demeaning by the British, and thus Macartney chose to genuflect as he would to his own sovereign George III. The Ambassador was repeatedly urged to perform the traditional Chinese kowtow, but as diplomat he felt it important to present George and Ch’ien-Lung as equals. This was not received positively by the Chinese who viewed their Emperor as the Son of Heaven with no human equal. According to their view the objects presented by the British in the ceremonial exchange of gifts were perceived as ‘tribute’ items, and Macartney as conveyor of tribute rather than legate of King George.

As well as presenting gifts to the Emperor, Macartney gave a letter to Ch’ien-Lung written by George III. The letter requested that Chinese officials controlling the port of Canton, hub of Anglo-Chinese trade and headquarters of the East India Company, reconsider the legislations they applied to foreign merchants. These rules were seen as dogmatic and limiting to British trading interests. George also asked for permission to establish an ambassador in Canton, who would oversee the expansion of British markets. In the event, these requests were declined by the Emperor, who saw no reason to oblige the demands of an ultimately rival Empire. He stated in an edict that China was entirely self-sufficient, and that everything he and his subjects needed could be manufactured domestically. There was no reason to allow an infiltration of British goods. There was no precedent for loosening Cantonese legislations and it was in China’s interest to preserve their dominion over the strategic port.

(Quelle:https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-emperor-of-china-receiving-the-macartney-embassy)

Die von dem britischen Biochemiker Joseph Needham (1900–1995) initiierte und anfangs herausgegebene englischsprachige Buchreihe zur Wissenschaft und Kultur in China setzte neue Maßstäbe in der Beschäftigung mit China im Wissenschaftsbereich. Als Standardwerk zur chinesischen Wissenschafts- und Technikgeschichte veränderte es die Wahrnehmung Chinas durch die westliche Welt und lenkte die Aufmerksamkeit auf die historischen wissenschaftlichen und technologischen Leistungen Chinas. Joseph Needham hatte das von ihm initiierte Projekt von 1954 an bis zu seinem Tod 1995 koordiniert. Zu Lebzeiten erschienen 17 Bände, weitere sieben Bände wurden seither durch das von Needham begründete Needham Research Institute herausgegeben. Das Erscheinen weiterer Bände ist in Vorbereitung. Die Gesamtanlage des Werkes ist etwas schwer zu überblicken. Die folgende Übersicht erhebt keinen Anspruch auf Aktualität oder Vollständigkeit.

| Band | Titel | Autor(en) | Jahr | Anm. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vol. 1 | Introductory Orientations | Wang Ling (research assistant) | 1954 | |

| Vol. 2 | History of Scientific Thought | Wang Ling (Forschungsassistent) | 1956 | OCLC 19249930 |

| Vol. 3 | Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and Earth | Wang Ling (Forschungsassistent) | 1959 | OCLC 177133494 |

| Vol. 4, Part 1 |

Physics and Physical Technology Physics |

Wang Ling (Forschungsassistent), with cooperation of Kenneth Robinson | 1962 | OCLC 60432528 |

| Vol. 4 Part 2 |

Physics and Physical Technology Mechanical Engineering |

Wang Ling (collaborator) | 1965 | |

| Vol. 4, Part 3 |

Physics and Physical Technology Civil Engineering and Nautics |

Wang Ling and Lu Gwei-djen (collaborators) | 1971 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 1 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Paper and Printing |

Tsien Tsuen-Hsuin | 1985 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 2 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Magisteries of Gold and Immortality |

Lu Gwei-djen (collaborator) | 1974 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 3 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Historical Survey, from Cinnabar Elixirs to Synthetic Insulin |

Ho Ping-Yu and Lu Gwei-djen (collaborators) | 1976 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 4 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus and Theory |

Lu Gwei-djen (collaborator), with contributions by Nathan Sivin | 1980 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 5 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Physiological Alchemy |

Lu Gwei-djen (collaborator) | 1983 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 6 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Military Technology: Missiles and Sieges |

Robin D.S. Yates, Krzysztof Gawlikowski, Edward McEwen, Wang Ling (collaborators) | 1994 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 7 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic |

Ho Ping-Yu, Lu Gwei-djen, Wang Ling (collaborators) | 1987 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 8 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Military Technology: Shock Weapons and Cavalry |

Lu Gwei-djen (collaborator) | 2011[1] | |

| Vol. 5, Part 9 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Textile Technology: Spinning and Reeling |

Dieter Kuhn | 1988 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 10 |

"Work in progress" | |||

| Vol. 5, Part 11 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Ferrous Metallurgy |

Donald B. Wagner | 2008 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 12 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Ceramic Technology |

Rose Kerr, Nigel Wood, contributions by Ts'ai Mei-fen and Zhang Fukang | 2004 | |

| Vol. 5, Part 13 |

Chemistry and Chemical Technology Mining |

Peter Golas | 1999 | |

| Vol. 6, Part 1 |

Biology and Biological Technology Botany |

Lu Gwei-djen (collaborator), with contributions by Huang Hsing-Tsung | 1986 | |

| Vol. 6, Part 2 |

Biology and Biological Technology Agriculture |

Francesca Bray | 1984 | |

| Vol. 6, Part 3 |

Biology and Biological Technology Agroindustries and Forestry |

Christian A. Daniels and Nicholas K. Menzies | 1996 | |

| Vol. 6, Part 4 |

Biology and Biological Technology Traditional Botany: An Ethnobotanical Approach |

Georges Métailie | 2015 | |

| Vol. 6, Part 5 |

Biology and Biological Technology Fermentations and Food Science |

Huang Hsing-Tsung | 2000 | |

| Vol. 6, Part 6 |

Biology and Biological Technology Medicine |

Lu Gwei-djen, Nathan Sivin (editor) | 2000 | |

| Vol. 7, Part 1 |

Language and Logic | Christoph Harbsmeier | 1998 | |

| Vol. 7, Part 2 |

General Conclusions and Reflections | Kenneth Girdwood Robinson (editor), Ray Huang (collaborator), introduction by Mark Elvin | 2004 | OCLC 779676 |

Il Milione è il resoconto dei viaggi in Asia di Marco Polo, intrapresi assieme al padre Niccolò Polo e allo zio paterno Matteo Polo, mercanti e viaggiatori veneziani, tra il 1271 e il 1295, e le sue esperienze alla corte di Kublai Khan, il più grande sovrano orientale dell'epoca, del quale Marco fu al servizio per quasi 17 anni.

Il libro fu scritto da Rustichello da Pisa, un autore di romanzi cavallereschi, che trascrisse sotto dettatura le memorie rievocate da Marco Polo, mentre i due si trovavano nelle carceri di San Giorgio a Genova.

Rustichello adoperò la lingua franco-veneta, una lingua culturale diffusa nel Nord Italia tra la fascia subalpina e il basso Po. Un'altra versione fu scritta in lingua d'oïl, la lingua franca dei crociati e dei mercanti occidentali in Oriente, forse nel 1298 ma sicuramente dopo il 1296. Secondo alcuni ricercatori, il testo sarebbe poi stato rivisto dallo stesso Marco Polo una volta rientrato a Venezia, con la collaborazione di alcuni frati dell'Ordine dei Domenicani.

Considerato un capolavoro della letteratura di viaggio, Il Milione è anche un'enciclopedia geografica, che riunisce in volume le conoscenze essenziali disponibili alla fine del XIII secolo sull'Asia, e un trattato storico-geografico.[5] È stato scritto che «Marco si rivolge a tutti quelli che vogliono sapere: sapere quello che c'è al di là delle frontiere della vecchia Europa. Non mette il suo libro sotto il segno dell'utile, ma sotto il segno della conoscenza».

Rispetto ad altre relazioni di viaggio scritte nel corso del XIII secolo, come la Historia Mongalorum di Giovanni da Pian del Carpine e l'Itinerarium di Guglielmo di Rubruck, Il Milione fu eccezionale perché le sue descrizioni si spingevano ben oltre il Karakorum e arrivarono fino al Catai. Marco Polo testimoniò l'esistenza di una civiltà mongola stanziale e molto sofisticata, assolutamente paragonabile alle civiltà europee: i mongoli, insomma, non erano solo i nomadi "selvaggi" che vivevano a cavallo e si spostavano in tenda, di cui avevano parlato Giovanni da Pian del Carpine e Guglielmo di Rubruck, ma abitavano città murate, sapevano leggere, e avevano usi e costumi molto sofisticati. Così come Guglielmo di Rubruck, invece, Marco smentisce alcune leggende sull'Asia di cui gli Europei all'epoca erano assolutamente certi.

Il Milione è stato definito come "la descrizione geografica, storica, etnologica, politica, scientifica (zoologia, botanica, mineralogia) dell'Asia medievale".Le sue descrizioni contribuirono alla compilazione del Mappamondo di Fra Mauro e ispirarono i viaggi di Cristoforo Colombo.

Ensemble de 15 volumes de format in 4° illustré de 179 planches gravées et numérotées.

Cette série célèbre l’histoire monumentale de la Chine XVIIIe siècle telle qu'en témoignent les missionnaires jésuites, dans tous ses aspects, militaires, agricoles, religieux, géographiques, généalogiques. Ces ouvrage de missionnaires tels que Cibot, Bourgeois, Poirot, Ko et Yang comprend des traductions d'ouvrages de droit chinois classiques, de maximes et de proverbes, ainsi que des essais sur la linguistique chinoise, l'actualité et l'observation scientifique. C’est une encyclopédie sur la Chine à l'usage des Européens.

Points remarquables :