漢德百科全書 | 汉德百科全书

Geschichte

Geschichte

L 1000 - 1500 nach Christus

L 1000 - 1500 nach Christus

Nobelpreis

Nobelpreis

Nobelpreis für Physiologie oder Medizin

Nobelpreis für Physiologie oder Medizin

Nobelpreis

Nobelpreis

Nobelpreis für Physik

Nobelpreis für Physik

Nobelpreis

Nobelpreis

Universität/Institut

Universität/Institut

Nobelpreis

Nobelpreis

Nobelpreis für Chemie

Nobelpreis für Chemie

Nobelpreis

Nobelpreis

Nobelpreis für Frieden

Nobelpreis für Frieden

Architektur

Architektur

Architektur

Architektur

Architektur der Gotik

Architektur der Gotik

Geschichte

Geschichte

Geschichte

Geschichte

L 1000 - 1500 nach Christus

L 1000 - 1500 nach Christus

Religion

Religion

Thüringen

Thüringen

Die Schlacht von Azincourt (französisch Bataille d’Azincourt, englisch Battle of Agincourt) fand am 25. Oktober 1415, am Tag des Heiligen Crispinian, bei Arras im heutigen nordfranzösischen Département Pas-de-Calais statt. Die Truppen von König Heinrich V. von England kämpften gegen das Heer König Karl VI. von Frankreich, verschiedener französischer Edelherren und der Armagnacs. Es war einer der größten militärischen Siege der Engländer über die Franzosen während des Hundertjährigen Kriegs.

阿金库尔战役(英语:Battle of Agincourt,法语:bataille d'Azincourt)发生于1415年10月25日,是英法百年战争中一场以少胜多的战役。在亨利五世的率领下,英格兰以由步兵弓箭手为主力的军队于此役击溃了法国由大批贵族组成的精锐骑士部队,为随后在1419年收复了整个诺曼底奠定基础。这场战役成为了英国中世纪最辉煌的胜利,也是一场在战争史有重要影响的战役。在此役中,英格兰出人意料地战胜了数量上占优势的法军,这提升了英格兰的士气和威望,削弱了法国,并开始了英国在百年战争中具有统治地位的新时期。

Unter dem Begriff Krone von Aragonien (spanisch Corona de Aragón, aragonesisch Corona d’Aragón, katalanisch Corona d’Aragó) werden Herrschaftsgebiete unterschiedlicher Verfasstheit zusammengefasst, die zwischen 1137 und 1516 bzw. 1714 in Personalunion von den Königen von Aragonien regiert wurden. Dazu gehörten die Königreiche Aragonien, Mallorca, Valencia, Sizilien, Sardinien, Korsika und Neapel, die Herzogtümer Athen und Neopatria, die Markgrafschaft Provence, das Fürstentum Katalonien (die Grafschaften Barcelona, Roussillon und Cerdanya) und die Herrschaft Montpellier.[1]

Die Herrscher der Krone von Aragonien und von Spanien zählten und zählen in ihrer Titulatur eine große Anzahl von Herrschaftsgebieten auf. Diese Aufzählungen entsprachen bzw. entsprechen aber nur zum Teil den wirklichen Herrschaftsverhältnissen.[2]

Von 1516 bis 1707 waren die einzelnen Herrschaftsgebiete der Krone von Aragonien Teile des Herrschaftsgebietes der Krone von Spanien. Dabei blieben die Staaten als solche und ein großer Teil ihrer Rechtstraditionen (Usatges) und Sonderrechte (Fueros) erhalten.

阿拉贡联合王国(加泰罗尼亚语:Corona d'Aragó;拉丁语:Corona Aragonum;西班牙语:Corona de Aragón[注 1])是一个复合君主国[1],同时也是指由阿拉贡王国及巴塞罗那伯国的君主统治的王国[2]和地区[3]的联邦。在14至15世纪,阿拉贡联合王国达到顶峰。此时它是具有制海权的国家,控制着西班牙东部、法国西南部以及远至希腊的地中海主要岛屿。除了在君主一级由国王统治,各个构成国的政治上并没有统一。每个王国具有自己的法律等一些权力。所以,阿拉贡联合王国和阿拉贡王国的区别在于后者是前者的一部分。1469年,阿拉贡王国和卡斯蒂利亚王国通过王朝婚姻联合[4]。1516年,两位国王的女儿胡安娜一世和外孙卡洛斯一世母子名义上成为两国的共治国王,但胡安娜事实上被卡洛斯囚禁。尽管这时的西班牙是一个分散的国家,但领土巩固的过程已经完成,统一于唯一君主之下。1555年胡安娜驾崩,卡洛斯成为唯一君主。这使得在卡洛斯的儿子费利佩二世年间,收复失地运动完成。1716年,费利佩五世在西班牙王位继承战争中获胜,加上新基本法令的颁布,西班牙王国得以建立。

教皇宫(法语:Palais des Papes)是座落于法国南部城市阿维尼翁的一座古老宫殿,為欧洲最大、最重要的中世纪哥特式建筑[1]。教皇宫不仅是教皇的宫殿,也是一座要塞。在十四世纪期间,阿维尼翁教皇宫是天主教教廷的所在地[N 1]。历史上有六次的教宗选举是在阿维尼翁教皇宫举行的,分别选出了本篤十二世(1334年)、克雷芒六世(1342年)、依諾增爵六世(1352年)、烏爾巴諾五世(1362年)、額我略十一世(1370年)和本篤十三世(1394年,对立教宗)。

教皇宫由内外两层建筑构成。分别是于本笃十二世时期建造的要塞式的旧宫,以及阿维尼翁教皇中最为奢侈的克莱孟六世时期在旧宫基础上扩建的新宫。教皇宫不仅是欧洲最宏大的哥特式建筑,同时也从各方面显示出了国际哥特式的风格。无论在建筑还是装饰方面,教皇宫都集中了当时代顶尖的大师的成就。其中包括了十四世纪法国著名的建筑师,皮埃尔·裴松以及让·德鲁夫,以及锡耶纳学派的壁画大师,西蒙涅·马尔蒂尼和马提欧·吉奥凡尼提。1995年,教宗宫和阿维尼翁历史中心被列为世界遗产[2]。

アヴィニョン教皇庁(フランス語: Palais des papes d'Avignon, ラテン語: Palatium paparum)は、1309年から1377年まで7代にわたる教皇のアヴィニョン捕囚から教会大分裂の時代、南フランスのアヴィニョンに設けられていた教皇宮殿(教皇庁)。

アヴィニョンに教皇が遷座された原因は、1303年の教皇ボニファティウス8世の死後、枢機卿団が分裂して教皇選挙の実施に困難が生じたこと、および、アナーニ事件の事後処理に絡んでフランス王フィリップ4世(端麗王)の干渉に求められるが、これらに加えイタリア半島における教皇領での無政府状態がそれに拍車をかけた[1]。

ローマ教会とフランス王国の対立における中立派として教皇に選出されたボルドー司教のクレメンス5世は1309年、フィリップ端麗王の干渉の下でのローマ入城を諦め、気に入った滞在先を求めてフランス中を旅した[1][2]。そして結局、一度もローマを訪れることなく、プロヴァンス伯領内にあり、現在は南仏ヴォクリューズ県の県庁所在地となっているアヴィニョンのドミニコ会修道院に落ち着き、そこに教皇庁を仮設した[1][2]。

続くヨハネス22世、ベネディクトゥス12世、クレメンス6世の3教皇は、アヴィニョンに城砦風の大宮殿と市街を取り囲む城壁の建造を進め、1348年、プロヴァンス女伯(兼ナポリ女王)ジョヴァンナが8万フローリンにものぼる金貨でアヴィニョン全市を購入、次のインノケンティウス6世の在位期間のうちに、難攻不落をめざした教皇領都市の建設が完遂した[1]。ベネディクトゥス12世はまた、アヴィニョンに図書館を設置する事業に取り組んでいる[3][注釈 1]。3教皇は同時に、教会組織における行政、司法、財政の諸改革を進めてそれぞれの機関も整備拡充され、南仏の金融活動や商工業とも結びついて、百年戦争であえぐフランス王国の窮乏を尻目に、それとはまったく対照的な隆盛と繁栄のときを迎えた[1][注釈 2]。

さらに、貧しい学生の支援に力を入れ、各地に大学を創設した教皇ウルバヌス5世や、同様に学芸の保護者として活動したグレゴリウス11世の時代には、クレメンス6世以降導入された優美なパリ風の宮廷文化とヒューマニズムが花ひらき、当時のヨーロッパ文化の一大中心地となり栄えた[1]。

なお、宮殿のうち「旧宮殿」はベネディクトゥス12世が旧司教館を取り壊させて同郷のミルポワ出身のピエール・ポアソンに依頼して築いたものであり、それに対しクレメンス6世がイル=ド=フランスの建築家ジャン・ド・ルーヴルに命じて築かせたのが「新宮殿」である[4]。

その一方で、教皇のローマ帰還の可能性は全期間を通じて、常に高まりを見せていた[1]。ルネサンスの詩人としてつとに有名なペトラルカ、あるいは「聖女」として知られていたドミニコ会修道女のシエナのカタリナらからの強い請願もあり、1367年から1370年にかけて、アヴィニョン教皇は経済力と軍事力を蓄積した上で一時ローマに復帰した[1][5]。そして1377年、ようやく正式に教皇のローマ帰還は実現にいたった[1]。しかしその後、枢機卿団は再度分裂し、フランス人教皇グレゴリウス11世がローマの民衆からひどい非難を浴びてアヴィニョンに戻り、クレメンス7世からベネディクトゥス13世にいたる教会大分裂の時代には、再びアヴィニョン教皇庁が利用された[1][5]。

The Palais des Papes (English: Palace of the Popes, lo Palais dei Papas in Occitan) is an historical palace located in Avignon, southern France. It is one of the largest and most important medieval Gothic buildings in Europe. Once a fortress and palace, the papal residence was the seat of Western Christianity during the 14th century. Six papal conclaves were held in the Palais, leading to the elections of Benedict XII in 1334, Clement VI in 1342, Innocent VI in 1352, Urban V in 1362, Gregory XI in 1370 and Antipope Benedict XIII in 1394.

Le Palais des papes d'Avignon est la plus grande des constructions gothiques du Moyen Âge1.

À la fois forteresse et palais, la résidence pontificale fut pendant le XIVe siècle le siège de la chrétienté d'OccidentN 1. Six conclaves se sont tenus dans le palais d'Avignon qui aboutirent à l'élection de Benoît XII, en 1335 ; de Clément VI, en 1342 ; d'Innocent VI, en 1352 ; d'Urbain V, en 1362 ; de Grégoire XI, en 1370, et de Benoît XIII, en 1394.

Le palais, qui est l'imbrication de deux bâtiments, le palais vieux de Benoît XII, véritable forteresse assise sur l'inexpugnable rocher des Doms, et le palais neuf de Clément VI, le plus fastueux des pontifes avignonnais, est non seulement le plus grand édifice gothique mais aussi celui où s'est exprimé dans toute sa plénitude le style du gothique international. Il est le fruit, pour sa construction et son ornementation, du travail conjoint des meilleurs architectes français, Pierre Peysson et Jean du Louvres, dit de Loubières, et des plus grands fresquistes de l'école siennoise, Simone Martini et Matteo Giovanetti.

De plus la bibliothèque pontificale d'Avignon, la plus grande d'Europe à l'époque avec 2 000 volumes, cristallisa autour d'elle un groupe de clercs passionnés de belles-lettres dont allait être issu Pétrarque, le fondateur de l'humanisme. Tandis que la chapelle clémentine, dite Grande Chapelle, attira à elle compositeurs, chantres et musiciens2. Ce fut là que Clément VI apprécia la Messe de Notre-Dame de Guillaume de Machault, que Philippe de Vitry, à son invité, put donner la pleine mesure de son Ars Nova et que vint étudier Johannes Ciconia.

Le palais fut aussi le lieu qui, par son ampleur, permit « une transformation générale du mode de vie et d'organisation de l'Église ». Il facilita la centralisation des services et l'adaptation de leur fonctionnement aux besoins pontificaux en permettant de créer une véritable administration3. Les effectifs de la Curie, de 200, à la fin du XIIIe siècle, étaient passés à 300 au début du XIVe siècle, pour atteindre 500 personnes en 1316. À cela s'ajoutèrent plus d'un millier de fonctionnaires laïcs qui purent œuvrer à l'intérieur du palais4.

Pourtant celui-ci qui, par sa structure et son fonctionnement, avait permis à l'Église de s'adapter « pour qu'elle puisse continuer à remplir efficacement sa mission3 » devint caduc quand les pontifes avignonnais jugèrent nécessaire de revenir à Rome. L'espoir d'une réconciliation entre les christianismes latin et orthodoxe, joint à l'achèvement de la pacification des États pontificaux en Italie, avaient donné des bases réelles à ce retourN 2.

À cela se joignit la conviction, pour Urbain V et Grégoire XI, que le siège de la papauté ne pouvait être que là où se trouvait le tombeau de Pierre, le premier pontife. Malgré les difficultés matérielles, l'opposition de la Cour de France et les fortes réticences du Collège des cardinaux, tous deux se donnèrent les moyens de rejoindre Rome. Le premier quitta Avignon le 30 avril 1362, le second le 13 septembre 1376 et cette fois l'installation fut définitive5.

En dépit du retour de deux antipapes, lors du Grand Schisme d'Occident, de la présence constante du XVe siècle au XVIIIe siècle de cardinaux-légats puis de vice-légats, le palais perdit toute sa splendeur d'antan mais conserva, en dehors de « l'œuvre de destruction » cet aspect que rapporte Montalembert.

« On ne saurait concevoir un ensemble plus beau dans sa simplicité, plus grandiose dans sa conception. C'est bien la papauté tout entière, debout, sublime, immortelle, étendant son ombre majestueuse sur le fleuve des nations et des siècles qui roule à ses pieds. »

— Charles de Montalembert, Du vandalisme en France - Lettre à M. Victor Hugo6

Le Palais des papes est classé monument historique sur la première liste des Monuments historique en 18408. Par ailleurs, depuis 1995, il est classé avec le centre historique d'Avignon, sur la liste du patrimoine mondial de l'Unesco, avec les critères culturels i, ii et iv9.

Il Palazzo dei Papi (in francese: Palais des Papes) di Avignone, in Francia è uno dei più grandi e importanti edifici gotici medievali in Europa.

Dal 1840 è monumento storico di Francia[1] e dal 1995 patrimonio mondiale dell'umanità[2].

Il palazzo venne costruito tra il 1335 e il 1364 sul naturale affioramento roccioso all'estremità nord-orientale della città, dominante il fiume Rodano. Al momento del suo completamento, occupava una superficie di 2,6 acri (11.000 m²). L'edificio fu incredibilmente costoso, e consumò gran parte delle entrate del papato durante la sua costruzione.

El palacio de los papas (en francés, palais des papes) en Aviñón (Francia) es uno de los edificios góticos más grandes e importantes medievales de Europa. Es uno de los muchos lugares a los que se llama «Palacio de los Papas». Se realizaron en el palacio seis cónclaves en los cuales se llevaron a cabo las elecciones de Benedicto XII (1335), Clemente VI (1342), Inocencio VI (1352), Urbano V (1362), Gregorio XI (1370) y Benedicto XIII (1394). El palacio, que está entrecruzado por dos edificios, es el antiguo palacio de Benedicto XII, una fortaleza asentada en la inexpugnable piedra de Amos, y el nuevo palacio de Clemente VI, el más suntuoso de los papas de Aviñón, ya que no solo es el más edificio gótico más grande, sino también en donde se expresa toda la plenitud del estilo del gótico internacional. Es el producto de la construcción y ornamentación de la labor conjunta de los mejores arquitectos franceses, Pierre Peysson y Jean du Louvres —asegura Jean de Loubières—, y los más importantes pintores de frescos de la escuela sienesa, Simone Martini y Matteo Giovanetti.

En 1840 fue objeto de una clasificación como monumento histórico por la lista de 1840.

Forma parte del Patrimonio de la Humanidad desde el año 1995, junto con el Petit Palais, la catedral y puente sobre el Ródano, además del antiguo recinto amurallado. Desde el año 2007 es considerado como Patrimonio europeo.1

Папский дворец (фр. Palais des papes d'Avignon) — памятник истории и архитектуры в Авиньоне, Франция. Объект Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО и один из крупнейших дворцов в Европе. Место проведения ежегодного театрального фестиваля.

Architektur

Architektur

Architektur der Gotik

Architektur der Gotik

Geschichte

Geschichte

L 1000 - 1500 nach Christus

L 1000 - 1500 nach Christus

Italien

Italien

Religion

Religion

Umbria

Umbria

Weltkulturerbe

Weltkulturerbe

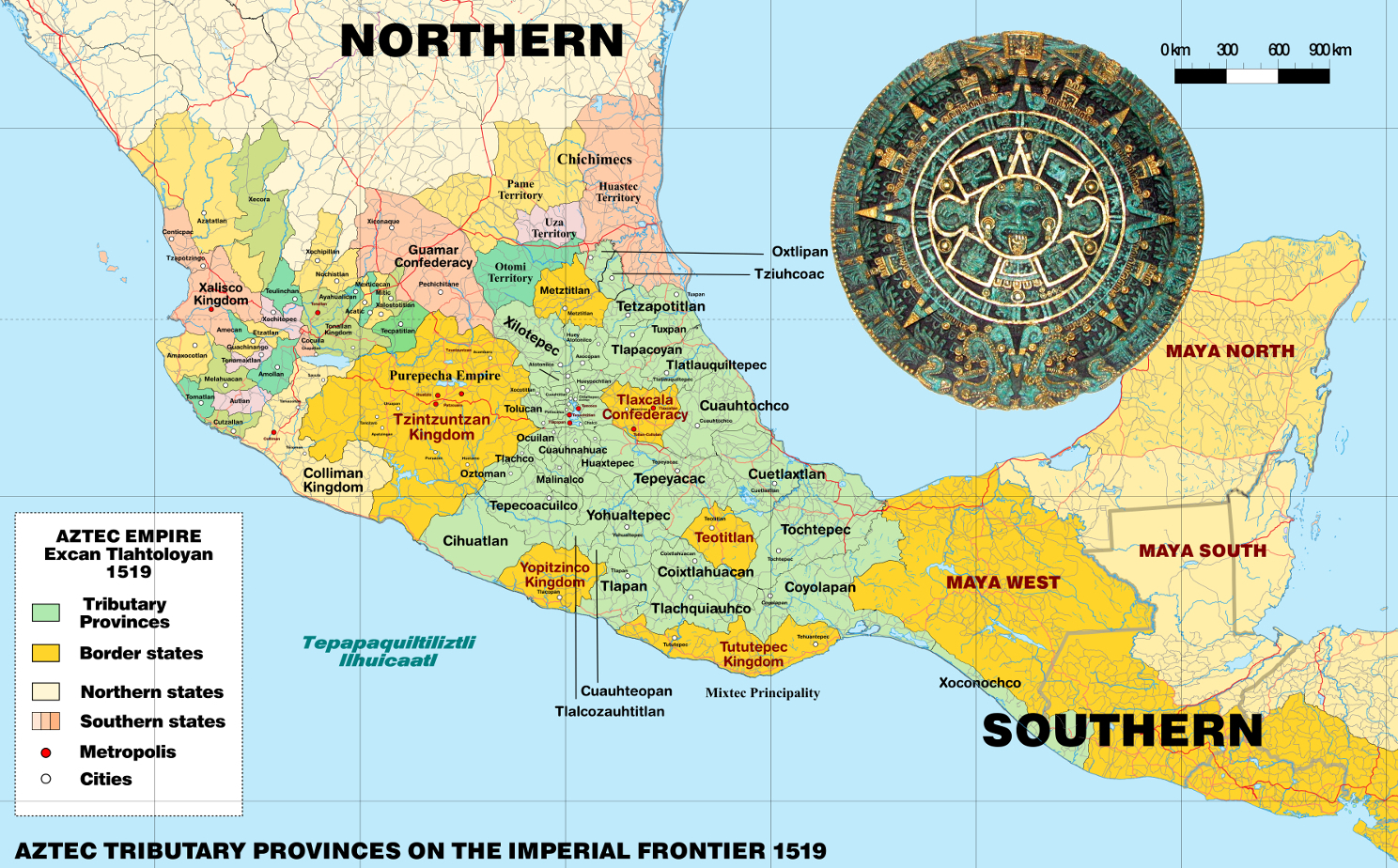

Die Azteken (von Nahuatl aztecatl, deutsch etwa „jemand, der aus Aztlán kommt“) waren eine mesoamerikanische Kultur, die zwischen dem 14. und dem frühen 16. Jahrhundert existierte. Im Allgemeinen bezeichnet man mit dem Begriff „Azteken“ die ethnisch heterogene, mehrheitlich Nahuatl sprechende Bevölkerung des Tals von Mexiko; im engeren Sinne sind damit aber nur die Bewohner von Tenochtitlán und der beiden anderen Mitglieder des sogenannten „Aztekischen Dreibundes“, der Städte Texcoco und Tlacopán, gemeint.

Ab dem späten 14. Jahrhundert weiteten die Azteken im Laufe der Jahre ihren politischen und militärischen Einfluss auf die umliegenden Städte und Völker aus, die nicht direkt dem Reich angegliedert, sondern zur Zahlung von Tributen gezwungen wurden. Auf dem Höhepunkt ihrer Macht kontrollierten sie weite Teile Zentralmexikos mit dem Tal von Mexiko als Zentrum. Zwischen 1519 und 1521 wurden die Azteken schließlich von den Spaniern unter Hernán Cortés unterworfen.

Die Azteken bezeichneten sich selbst meist als Mexica [meːˈʃiʔkaʔ], nach dem Namen des Ortes oder der Region Mexico – der Ursprung des heutigen Ländernamens Mexiko – bzw., nach ihren Siedlungsplätzen Tlatelolco und Tenochtitlán, auch Tlatelolca [tɬateˈloːlkaʔ] und Tenochca [teˈnoːtʃkaʔ]. In alten Quellen wird der Begriff „Azteken“ nur im Zusammenhang mit dem mythischen Herkunftsort Aztlán verwendet. Der erste, der ihn in moderner Zeit benutzte, war der Jesuit Francisco Javier Clavijero im 18. Jahrhundert; bekannt wurde er jedoch erst durch Alexander von Humboldt.

阿兹特克或阿兹台克是存在于14世纪至16世纪的墨西哥古文明,主要分布在墨西哥中部和南部,因阿兹特克人而得名。阿兹特克人包括墨西哥谷地的多个民族,以操纳瓦特尔语的族群为主。阿兹特克文明在政治上的基本单位是城邦,有些城邦组成政治联盟或政治邦联。其中,1427年建立的阿兹特克帝国最具影响力,帝国由墨西加城邦特诺奇蒂特兰、阿科尔瓦城邦特斯科科以及特帕内克城邦特拉科潘组成,政治影响力深远,领土范围极盛时东抵墨西哥湾,西至太平洋,南达恰帕斯和危地马拉。由于其强大的历史影响力,“阿兹特克”在狭义上常特指阿兹特克帝国;但广义来说,在殖民者入侵之前抑或是在西班牙殖民时代,中部美洲的所有纳瓦人政体和族群都可划作阿兹特克文明的一部分[1][2]。

阿兹特克人于约12世纪末由北方迁入墨西哥谷地,这里人口稠密,后来成为阿兹特克城邦崛起的中心。墨西加人是阿兹特克人的主要分支,他们在特斯科科湖中的岛礁建立起特诺奇蒂特兰城邦,并定居于此。1427年,特诺奇蒂特兰和特斯科科、特拉科潘结盟,联合击退了曾支配谷地的特帕内克城邦阿斯卡波察尔科。此三邦的联盟在后世被称为阿兹特克帝国,在随后的百余年内通过武力和贸易攻势展开扩张,成长为中部美洲势力范围最庞大的城邦联盟[3]。尽管被称为帝国,阿兹特克帝国事实上是一个以朝贡体系为基础的“朝贡帝国”,依托于扶植傀儡君主、政治联姻以及思想控制的方式间接控制其他城邦,强制其定期向宗主进贡,并不以军事驻防的方式实行直接统治[4]。帝国借此限制各邦同外部的贸易联系,使其属邦越发依赖帝国中央[5]。1519年,阿兹特克帝国的领土达到极盛,但一年后即迎来了欧洲人的历史性的访问。1520年,西班牙殖民者埃尔南·科尔特斯一行抵达中部美洲。科尔特斯利用中部美洲城邦间的矛盾,和阿兹特克的敌对城邦结盟,在1521年攻陷特诺奇蒂特兰,俘获并处决特拉托阿尼夸乌特莫克,并在特诺奇蒂特兰的废墟之上建起了现代墨西哥城。科尔特斯以此为中心实现对中部美洲全境的征服和殖民,将之纳入西班牙殖民帝国[6]。

近现代对阿兹特克文明的大规模研究始于19世纪,随着考古发掘和文献研究工作的进行,阿兹特克文明的文化、艺术和宗教逐渐为世人所了解。除了考古工作发现的古建筑和古物件外,既有的书面文献也起到重要作用,包括原住民手抄本、西班牙征服者的纪实文学,以及16世纪和17世纪由西班牙牧师或是有读写能力的阿兹特克人编撰的文化和历史文献等。十二卷手抄本佛罗伦萨手抄本是其中较为著名的文献,由方济各会修士贝尔纳迪诺·德萨阿贡结合一些阿兹特克人的描述写成,完整全面地记录了阿兹特克文明的文化、宗教、社会、经济和历史样貌。

德国地理学家冯·洪堡在19世纪早期率先用“阿兹特克”一词指代中部美洲纳瓦人以贸易、习俗、宗教、语言或政治联盟为纽带联系起来的文明集合体,“阿兹特克”一词就此被学界广泛接受和使用。不过,阿兹特克的具体界定也仍是一直以来学术讨论的主题之一[7]。根据中部美洲历史的断代法共识,900年至1521年的后古典时期内,中部美洲的绝大部分族群都拥有大体类似的文化烙印。因此,大部分普遍认为象征阿兹特克文明的文化元素并不是阿兹特克帝国的专属,因此对“阿兹特克文明”概念更贴切的理解是一种普遍存在的中部美洲文化体系[8],其农业以玉米栽培为主,社会形成皮尔利贵族和马塞瓦尔利平民的阶级分野,崇拜以特斯卡特利波卡、特拉洛克和克察尔科亚特尔为主的神系,历法系统由365天一周期的太阳历内嵌260天一周期的神圣历组成。与之相对应地,守护神祇维齐洛波奇特利、双子金字塔和阿兹特克陶制品则是阿兹特克人独有的文化符号[8]。现代墨西哥国家建立后,阿兹特克文化作为其国土上曾存在的重要文化而成为其现代国家认同的根基之一。特诺奇蒂特兰建城传说中雄鹰衔长蛇立于仙人掌之上的经典场面出现在墨西哥国旗和国徽上,为其重要的国家象征之一。

アステカ(Azteca、古典ナワトル語: Aztēcah)とは1428年頃から1521年までの約95年間北米のメキシコ中央部に栄えたメソアメリカ文明の国家。メシカ(古典ナワトル語: mēxihcah メーシッカッ)、アコルワ、テパネカの3集団の同盟によって支配され、時とともにメシカがその中心となった。言語は古典ナワトル語(ナワトル語)。

The Aztecs (/ˈæztɛks/) were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec peoples included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica from the 14th to the 16th centuries. Aztec culture was organized into city-states (altepetl), some of which joined to form alliances, political confederations, or empires. The Aztec empire was a confederation of three city-states established in 1427, Tenochtitlan, city-state of the Mexica or Tenochca; Texcoco; and Tlacopan, previously part of the Tepanec empire, whose dominant power was Azcapotzalco. Although the term Aztecs is often narrowly restricted to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, it is also broadly used to refer to Nahua polities or peoples of central Mexico in the prehispanic era,[1] as well as the Spanish colonial era (1521–1821).[2] The definitions of Aztec and Aztecs have long been the topic of scholarly discussion, ever since German scientist Alexander von Humboldt established its common usage in the early nineteenth century.[3]

Most ethnic groups of central Mexico in the post-classic period shared basic cultural traits of Mesoamerica, and so many of the traits that characterize Aztec culture cannot be said to be exclusive to the Aztecs. For the same reason, the notion of "Aztec civilization" is best understood as a particular horizon of a general Mesoamerican civilization.[4] The culture of central Mexico includes maize cultivation, the social division between nobility (pipiltin) and commoners (macehualtin), a pantheon (featuring Tezcatlipoca, Tlaloc and Quetzalcoatl), and the calendric system of a xiuhpohualli of 365 days intercalated with a tonalpohualli of 260 days. Particular to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan was the patron God Huitzilopochtli, twin pyramids, and the ceramic ware known as Aztec I to IV.[5]

From the 13th century, the Valley of Mexico was the heart of dense population and the rise of city-states. The Mexica were late-comers to the Valley of Mexico, and founded the city-state of Tenochtitlan on unpromising islets in Lake Texcoco, later becoming the dominant power of the Aztec Triple Alliance or Aztec Empire. It was a tributary empire that expanded its political hegemony far beyond the Valley of Mexico, conquering other city states throughout Mesoamerica in the late post-classic period. It originated in 1427 as an alliance between the city-states Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan; these allied to defeat the Tepanec state of Azcapotzalco, which had previously dominated the Basin of Mexico. Soon Texcoco and Tlacopan were relegated to junior partnership in the alliance, with Tenochtitlan the dominant power. The empire extended its reach by a combination of trade and military conquest. It was never a true territorial empire controlling a territory by large military garrisons in conquered provinces, but rather dominated its client city-states primarily by installing friendly rulers in conquered territories, by constructing marriage alliances between the ruling dynasties, and by extending an imperial ideology to its client city-states.[6] Client city-states paid tribute to the Aztec emperor, the Huey Tlatoani, in an economic strategy limiting communication and trade between outlying polities, making them dependent on the imperial center for the acquisition of luxury goods.[7] The political clout of the empire reached far south into Mesoamerica conquering polities as far south as Chiapas and Guatemala and spanning Mesoamerica from the Pacific to the Atlantic oceans.

The empire reached its maximal extent in 1519, just prior to the arrival of a small group of Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés. Cortés allied with city-states opposed to the Mexica, particularly the Nahuatl-speaking Tlaxcalteca as well as other central Mexican polities, including Texcoco, its former ally in the Triple Alliance. After the fall of Tenochtitlan on August 13, 1521 and the capture of the emperor Cuauhtemoc, the Spanish founded Mexico City on the ruins of Tenochtitlan. From there they proceeded with the process of conquest and incorporation of Mesoamerican peoples into the Spanish Empire. With the destruction of the superstructure of the Aztec Empire in 1521, the Spanish utilized the city-states on which the Aztec Empire had been built, to rule the indigenous populations via their local nobles. Those nobles pledged loyalty to the Spanish crown and converted, at least nominally, to Christianity, and in return were recognized as nobles by the Spanish crown. Nobles acted as intermediaries to convey tribute and mobilize labor for their new overlords, facilitating the establishment of Spanish colonial rule.[8]

Aztec culture and history is primarily known through archaeological evidence found in excavations such as that of the renowned Templo Mayor in Mexico City; from indigenous writings; from eyewitness accounts by Spanish conquistadors such as Cortés and Bernal Díaz del Castillo; and especially from 16th- and 17th-century descriptions of Aztec culture and history written by Spanish clergymen and literate Aztecs in the Spanish or Nahuatl language, such as the famous illustrated, bilingual (Spanish and Nahuatl), twelve-volume Florentine Codex created by the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, in collaboration with indigenous Aztec informants. Important for knowledge of post-conquest Nahuas was the training of indigenous scribes to write alphabetic texts in Nahuatl, mainly for local purposes under Spanish colonial rule. At its height, Aztec culture had rich and complex mythological and religious traditions, as well as achieving remarkable architectural and artistic accomplishments.

Les Aztèques, ou Mexicas (du nom de leur capitale, Mexico-Tenochtitlan), étaient un peuple amérindien du groupe nahua, c'est-à-dire de langue nahuatl.

Ils s'étaient définitivement sédentarisés dans le plateau central du Mexique, dans la vallée de Mexico, sur une île du lac Texcoco, vers le début du XIVe siècle. Au début du XVIe siècle, ils avaient atteint un niveau de civilisation parmi les plus avancés d'Amérique et dominaient, avec les autres membres de leur Triple alliance, le plus vaste empire de la Mésoamérique postclassique. Leur seul vrai rival était le royaume tarasque.

L'arrivée, en 1519, des conquistadors menés par Hernán Cortés scella la fin de leur règne. Le 13 août 1521, les Espagnols, aidés par un grand nombre d’alliés autochtones, finirent par remporter le siège de Tenochtitlan et par capturer le dernier dirigeant aztèque, Cuauhtémoc. La civilisation aztèque s'est alors rapidement acculturée à l'époque coloniale ; il en résulte un profond syncrétisme dans le Mexique actuel entre les héritages aztèques (et, plus largement, mésoaméricains) et espagnols.

Les études de cette civilisation précolombienne se fondent sur les codex mésoaméricains, livres écrits par les autochtones sur papier d'amate, les témoignages des conquistadors, comme Hernán Cortés et Bernal Díaz del Castillo, les travaux des chroniqueurs du XVIe et XVIIe siècles, comme le codex de Florence compilé par le moine franciscain Bernardino de Sahagún avec l'aide de collaborateurs aztèques, ainsi que, depuis la fin du XVIIIe siècle, les recherches archéologiques, grâce aux fouilles comme celles du Templo Mayor de la ville de Mexico.

I Mexica (pron. mescìca; Nahuatl: Mēxihcah [meːˈʃiʔkaʔ], singolare Mēxihcatl) o Mexicas — meglio noti come Aztechi nella storiografia occidentale - furono una delle grandi civiltà precolombiane, la più florida e viva al momento del contatto con gli Spagnoli. Provenienti dalla California settentrionale, si svilupparono nella regione mesoamericana dell'attuale Messico dal secolo XIV al XVI.

Il nome con cui essi stessi si indicavano è "Mexica" o "Tenochca", e non Aztechi, non a caso Mexica è tuttora il termine usato per definire i loro discendenti; il termine Azteco è invece stato coniato solo molti secoli dopo dal geografo tedesco Alexander von Humboldt per distinguere queste popolazioni precolombiane dall'insieme dei Messicani moderni. Spesso con il termine "azteco" ci si riferisce esclusivamente al popolo residente a Tenochtitlán (dove oggi si trova Città del Messico), situata su un'isola del lago Texcoco, che faceva riferimento a se stessa come Mēxihcah Tenochcah [meːˈʃiʔkaʔ teˈnot͡ʃkaʔ] o Cōlhuah Mēxihcah [ˈkoːlwaʔ meːˈʃiʔkaʔ].

Talvolta il termine comprende anche gli abitanti delle due principali città-stato alleate di Tenochtitlan, gli Acolhua di Texcoco e i Tepanechi di Tlacopan, che insieme con i Mexica formavano la Triplice alleanza azteca spesso conosciuta come "impero azteco". In altri contesti, "azteco" può riferirsi a tutti i vari stati della città e dei loro popoli che hanno condiviso gran parte della loro storia etnica e tratti culturali con i Mexica, con gli Acolhua e con i Tepanechi e che spesso utilizzavano la lingua nahuatl come lingua franca. In questo senso si può parlare di una civiltà azteca comprensiva di tutti i modelli culturali comuni per la maggior parte dei popoli che abitarono il Messico centrale nel periodo tardo post-Classico.

A partire dal XIII secolo, la Valle del Messico è stata il cuore della civiltà azteca; qui la capitale della Triplice alleanza azteca, la città di Tenochtitlan, fu costruita su isole nel lago Texcoco. La Triplice Alleanza formò un impero tributario che espanse la propria egemonia politica ben oltre la Valle del Messico, conquistando altre città di tutto il Mesoamerica. Al suo apice, la cultura azteca vantava ricche e complesse tradizioni mitologiche e religiose, oltre ad aver raggiunto la capacità di realizzare notevoli manufatti architettonici e artistici. Nel 1521 Hernán Cortés, conquistò Tenochtitlan e sconfisse la Triplice alleanza azteca che al momento si trovava sotto la guida di Montezuma II (vedi Conquista dell'impero azteco). Successivamente, gli spagnoli fondarono il nuovo insediamento di Città del Messico sul sito della capitale azteca in rovina; da qui poi procedettero con il processo di colonizzazione dell'America Centrale.

La cultura e la storia azteca sono conosciute principalmente attraverso le testimonianze archeologiche rinvenute negli scavi, come quello del famoso Templo Mayor a Città del Messico; da codici scritti su corteccia; da testimonianze oculari dei conquistadores spagnoli come Hernán Cortés e Bernal Díaz del Castillo; e soprattutto dalle descrizioni del XVI e XVII secolo della cultura e della storia scritti da ecclesiastici spagnoli e da letterati Aztechi, come il famoso Codice Fiorentino compilato dal frate francescano Bernardino de Sahagún con l'aiuto di informatori originari aztechi.

Los mexicas (del náhuatl mēxihcah ![]() [meː'ʃiʔkaʔ] (?·i), «mexicas»1) —llamados en la historiografía tradicional aztecas2— fueron un pueblo mesoamericano de filiación nahua que fundó México-Tenochtitlan y hacia el siglo XV en el periodo posclásico tardío se convirtió en el centro de uno de los Estados más extensos que se conoció en Mesoamérica, asentado en un islote al poniente del lago de Texcoco, sobre los márgenes centro y el sur de los lagos, como en Huexotla, Coatlinchan, Culhuacan, Iztapalapa, Chalco, Xico, Xochimilco, Tacuba, Azcapotzalco, Tenayuca y Xaltocan, hacia finales del Posclásico Temprano (900-1200),3 hoy prácticamente desecado. Sobre el islote se asienta la actual Ciudad de México, y que corresponde a la misma ubicación geográfica. Aliados con otros pueblos de la cuenca lacustre del valle de México —Tlacopan y Texcoco—, los mexicas sometieron a varias poblaciones indígenas que se asentaron en el centro y sur del territorio actual de México agrupados territorialmente en altépetl.

[meː'ʃiʔkaʔ] (?·i), «mexicas»1) —llamados en la historiografía tradicional aztecas2— fueron un pueblo mesoamericano de filiación nahua que fundó México-Tenochtitlan y hacia el siglo XV en el periodo posclásico tardío se convirtió en el centro de uno de los Estados más extensos que se conoció en Mesoamérica, asentado en un islote al poniente del lago de Texcoco, sobre los márgenes centro y el sur de los lagos, como en Huexotla, Coatlinchan, Culhuacan, Iztapalapa, Chalco, Xico, Xochimilco, Tacuba, Azcapotzalco, Tenayuca y Xaltocan, hacia finales del Posclásico Temprano (900-1200),3 hoy prácticamente desecado. Sobre el islote se asienta la actual Ciudad de México, y que corresponde a la misma ubicación geográfica. Aliados con otros pueblos de la cuenca lacustre del valle de México —Tlacopan y Texcoco—, los mexicas sometieron a varias poblaciones indígenas que se asentaron en el centro y sur del territorio actual de México agrupados territorialmente en altépetl.

Los mexicas se caracterizaban por la explotación de cultivos altamente simbióticos (dependencia a la manipulación humana,4556 como maíz, chile, calabaza, frijol, etc.), el uso extensivo de plumas para la confección de vestimentas, el uso de calendarios astronómicos (uno ritual de 260 días y un civil de 365), una sofisticada metalurgia prehispánica ornamental y militar basada principalmente en el bronce, oro y plata;7 una escritura en forma de pictogramas el cual era usado para la documentación de hechos y el cálculo de obras arquitectónicas el cual estaba basado en un sistema métrico propio,8 que para mediciones de terrenos es comparable con otros sistemas de medida de la Edad Moderna,9 el uso extensivo de productos derivados de las cactáceas y agaves, y el uso de cerámico ígneo (obsidiana) para fines quirúrgicos y bélicos.

Ацте́ки, или асте́ки[1] (самоназв. mēxihcah [meː'ʃiʔkaʔ]), — индейский народ в центральной Мексике. Численность современных науа, как ещё называют ацтеков, — свыше 1,5 млн человек. Цивилизация ацтеков (XIV—XVI века) обладала богатой мифологией и культурным наследием. Столицей империи ацтеков был город Теночтитлан, расположенный на озере Тескоко, там, где сейчас располагается город Мехико.

Steiermark

Steiermark

Finanz

Finanz

Historische Münzen, Banknoten

Historische Münzen, Banknoten

Militär,Verteidigung und Ausrüstung

Militär,Verteidigung und Ausrüstung

Royalty

Royalty

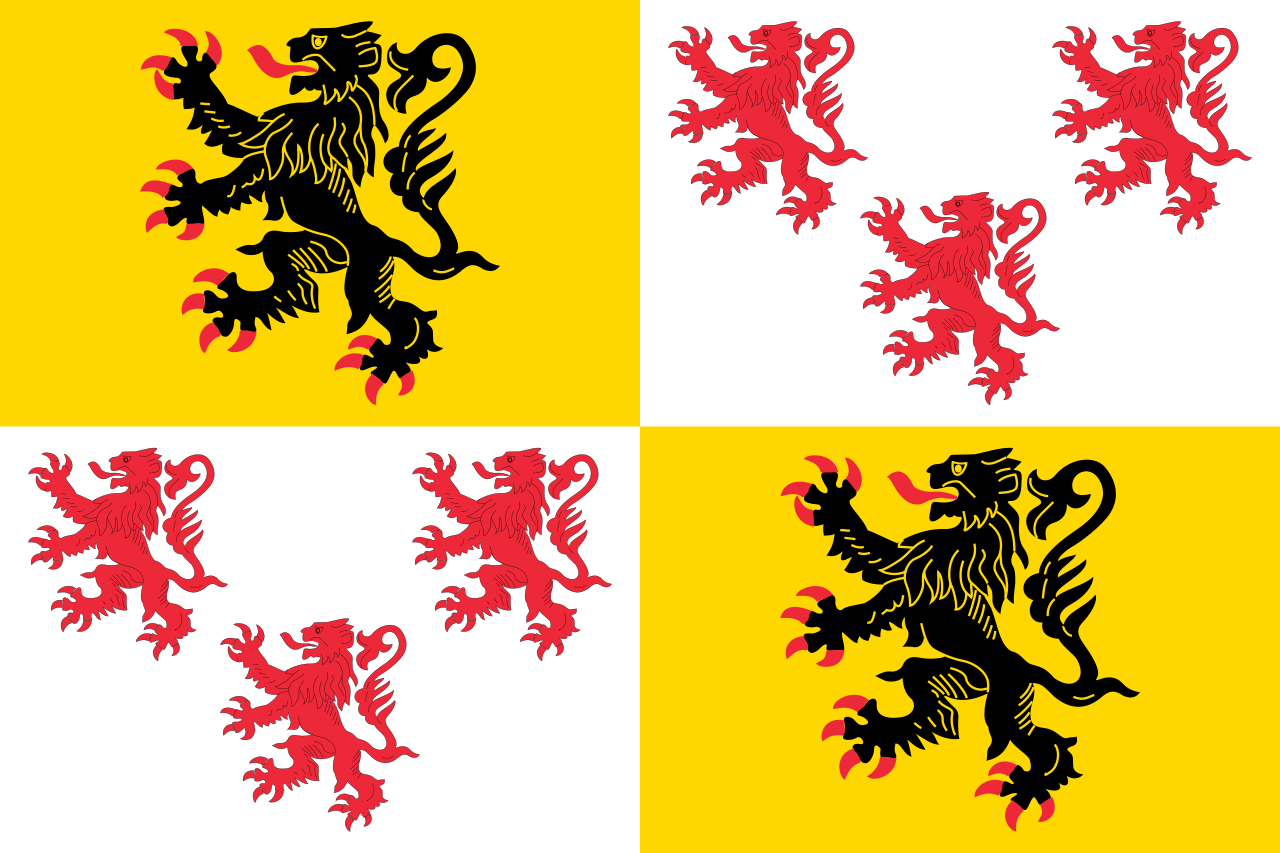

Hauts-de-France

Hauts-de-France

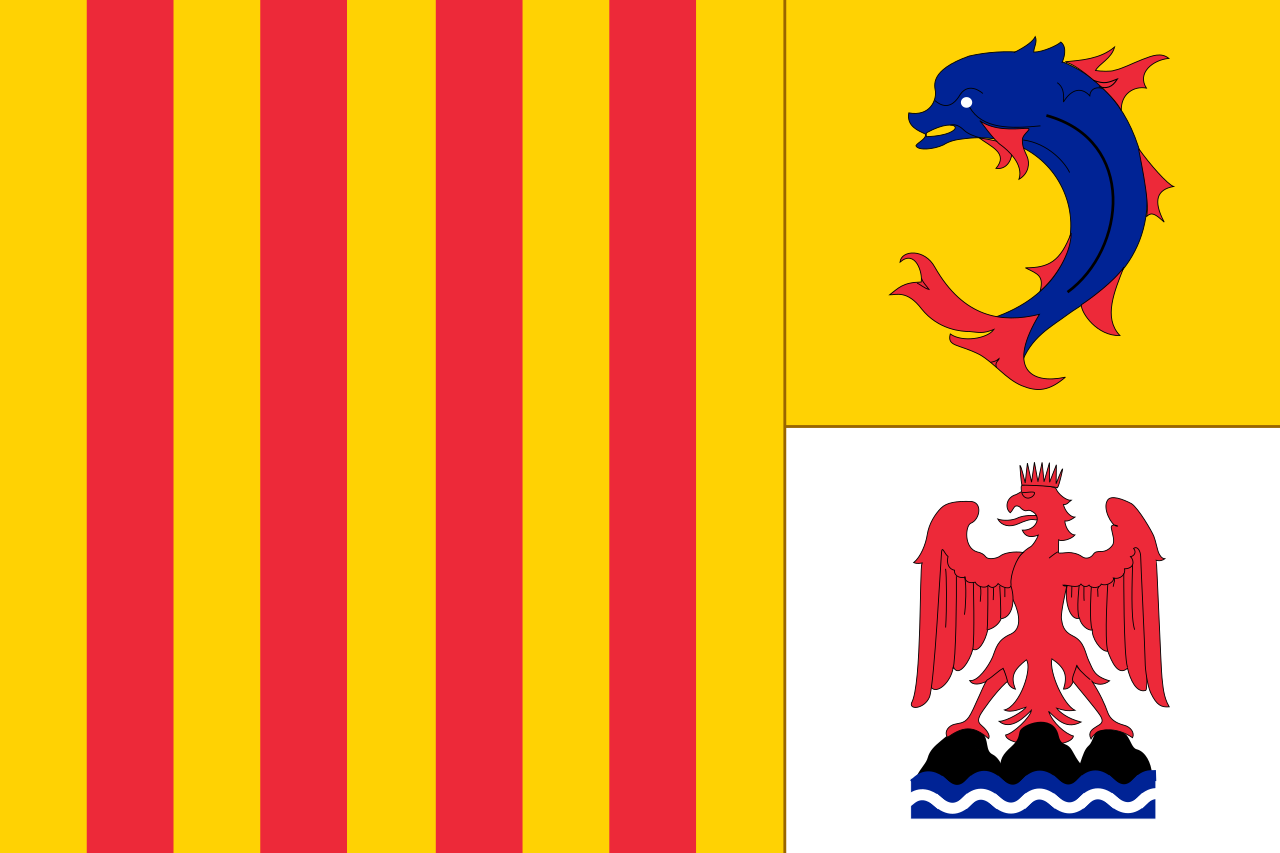

Provence-Alpes-Côte d´Azur

Provence-Alpes-Côte d´Azur

Zivilisation

Zivilisation