Deutsch-Chinesische Enzyklopädie, 德汉百科

History

History

C 4000 - 3000 BC

C 4000 - 3000 BC

History

History

B 5000 - 4000 BC

B 5000 - 4000 BC

History

History

D 3000 - 2500 BC

D 3000 - 2500 BC

History

History

E 2500 - 2000 BC

E 2500 - 2000 BC

History

History

F 2000 - 1500 BC

F 2000 - 1500 BC

History

History

G 1500 - 1000 BC

G 1500 - 1000 BC

History

History

H 1000 - 500 BC

H 1000 - 500 BC

History

History

I 500 - 0 BC

I 500 - 0 BC

Iraq

Iraq

Mesopotamian civilization

Mesopotamian civilization

美索不达米亚(阿拉米语:ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪܝܢ,希腊语:Μεσοποταμία,阿拉伯语:بلاد الرافدين ,英语:Mesopotamia)是古希腊对两河流域的称谓,意为“(两条)河流之间的地方”[1],这两条河指的是幼发拉底河和底格里斯河,在两河之间的美索不达米亚平原上产生和发展的古文明称为两河文明或美索不达米亚文明,它大体位于现今的伊拉克,其存在时间从公元前6000年到公元前2世纪,是人类最早的文明。由于这两条河流每年的氾滥,所以下游土壤肥沃,富含有机物和矿物质,但同时该地气候干旱缺水,所以当地人公元前6000年就开始运用灌溉技术[2],灌溉为当地带来了大规模的人力协作和农业丰产。经过数千年的演化,美索不达米亚于公元前2900年左右形成成熟文字、众多城市及周围的农业社会[3]。

由于美索不达米亚地处平原,而且周围缺少天然屏障,所以在几千年的历史中有多个民族在此经历了接触、入侵、融合的过程,苏美尔人、阿卡德人、阿摩利人、亚述人、埃兰人、喀西特人、胡里特人、迦勒底人等其他民族先后进入美索不达米亚,他们先经历了史前的欧贝德、早期的乌鲁克、苏美尔和阿卡德时代、古提王朝、新苏美尔时期的拉格什第二王朝、乌鲁克和乌尔第三王朝、后来又建立起先进的古巴比伦、庞大的亚述帝国。迦勒底人建立的新巴比伦将美索不达米亚古文明推向鼎盛时期。但随着波斯人和希腊人的先后崛起和征服,已经辉煌了几千年的文字和城市逐步被荒废,接着渐渐为沙尘掩埋,最后被人们所遗忘。直到19世纪中期,伴随考古发掘的开始和亚述学的兴起,越来越多的实物被出土,同时楔形文字逐渐被破解,尘封了18个世纪的美索不达米亚古文明才慢慢呈现在当今世人面前。

苏美尔人于公元前3200年左右发明的楔形文字[4]、公元前2100年左右尼普尔的书吏学校[5]、三四千年前苏美尔人和巴比伦人的文学作品[6]、2600多年前藏有2.4万块泥板书的亚述巴尼拔图书馆[7]、有前言和后记及282条条文构成的《汉谟拉比法典》[8]、有重达30多吨的人面带翼神兽守卫的亚述君王宫殿、古巴比伦人关于三角的代数的运算、公元前747年巴比伦人对日蚀和月蚀的准确预测[9]、用琉璃砖装饰的新巴比伦城和传说中的巴别塔和巴比伦空中花园,以及各时期的雕塑和艺术品,这些成就都属于美索不达米亚这个古老的文明。

Mesopotamien oder Zweistromland (altgriechisch Μεσοποταμία Mesopotamia; aramäisch ܒܬ ܢܗܪܝܢ Beth Nahrin; arabisch بلاد الرافدين, DMG Bilād ar-rāfidain; persisch میان رودان Miyān roodan; kurdisch/türkisch Mezopotamya) bezeichnet die Kulturlandschaft in Vorderasien, die durch die großen Flusssysteme des Euphrat und Tigris geprägt wird.

Zusammen mit Anatolien, der Levante im engeren Sinne und dem Industal gehört es zu den wichtigen kulturellen Entwicklungszentren des Alten Orients. Mit der Levante bildet es einen großen Teil des sogenannten Fruchtbaren Halbmonds, in welchem sich Menschen erstmals dauerhaft niederließen. Es entwickelten sich Stadtstaaten, Königreiche – Neuerungen für die Menschheit mit den Erfindungen der Schrift, der ersten Rechtsordnung, der ersten Menschheitshymnen, des Ziegelsteins, des Streitwagens, des Biers und der Keramik: Evolutionen in der Stadtentwicklung, Kultur- und Technikgeschichte. Im Süden mit den Sumerern, durchsetzt von gutäischen Königsdynastien, entwickelte sich die erste Hochkultur der Menschheitsgeschichte. Ihnen folgten die Akkader, Babylonier, im Norden das Königreich Mittani, in Mittelmesopotamien die Assyrer, dann das medische Königreich, welches das assyrische Großreich in einer Union mit den Babyloniern eroberte. Die Meder hatten fast 200 Jahre ein Großreich inne, ehe mit den Persern erstmals eine außerhalb Mesopotamiens entstandene Kultur dauerhafte Kontrolle über die Region erlangte. Auf die Perser folgten die Makedonier, Parther, Sassaniden, Araber und schließlich die Osmanen, deren Herrschaft im 17. Jahrhundert durch die persischen Safawiden kurzzeitig unterbrochen wurde.

Das vor allem in seiner Wasserverfügbarkeit höchst unterschiedliche Land bot den dort lebenden Menschen zu allen Zeiten höchst unterschiedliche Siedlungsvoraussetzungen, die massiven Einfluss auf die historische Entwicklung nahmen.

メソポタミア(ギリシャ語: Μεσοποταμία、ラテン文字転写: Mesopotamia、ギリシャ語で「複数の河の間」)は、チグリス川とユーフラテス川の間の沖積平野である。現在のイラクの一部にあたる。

古代メソポタミア文明は、メソポタミアに生まれた複数の文明を総称する呼び名で、世界最古の文明であるとされてきた。文明初期の中心となったのは民族系統が不明のシュメール人である。

地域的に、北部がアッシリア、南部がバビロニアで、バビロニアのうち北部バビロニアがアッカド、下流地域の南部バビロニアがシュメールとさらに分けられる。南部の下流域であるシュメールから、上流の北部に向かって文明が広がっていった。土地が非常に肥沃で、数々の勢力の基盤となったが、森林伐採の過多などで、上流の塩気の強い土が流れてくるようになり、農地として使えない砂漠化が起きた。

古代メソポタミアは、多くの民族の興亡の歴史である。 例えば、シュメール、バビロニア(首都バビロン)、アッシリア、アッカド(ムロデ王国の四つの都市のひとつ)、ヒッタイト、ミタンニ、エラム、古代ペルシャ人の国々があった。古代メソポタミア文明は、紀元前4世紀、アレクサンドロス3世(大王)の遠征によってその終息をむかえヘレニズムの世界の一部となる。

Mesopotamia (Greek: Μεσοποταμία) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent, in modern days roughly corresponding to most of Iraq, Kuwait, the eastern parts of Syria, Southeastern Turkey, and regions along the Turkish–Syrian and Iran–Iraq borders.[1]

The Sumerians and Akkadians (including Assyrians and Babylonians) dominated Mesopotamia from the beginning of written history (c. 3100 BC) to the fall of Babylon in 539 BC, when it was conquered by the Achaemenid Empire. It fell to Alexander the Great in 332 BC, and after his death, it became part of the Greek Seleucid Empire.

Around 150 BC, Mesopotamia was under the control of the Parthian Empire. Mesopotamia became a battleground between the Romans and Parthians, with western parts of Mesopotamia coming under ephemeral Roman control. In AD 226, the eastern regions of Mesopotamia fell to the Sassanid Persians. The division of Mesopotamia between Roman (Byzantine from AD 395) and Sassanid Empires lasted until the 7th century Muslim conquest of Persia of the Sasanian Empire and Muslim conquest of the Levant from Byzantines. A number of primarily neo-Assyrian and Christian native Mesopotamian states existed between the 1st century BC and 3rd century AD, including Adiabene, Osroene, and Hatra.

Mesopotamia is the site of the earliest developments of the Neolithic Revolution from around 10,000 BC. It has been identified as having "inspired some of the most important developments in human history, including the invention of the wheel, the planting of the first cereal crops, and the development of cursive script, mathematics, astronomy, and agriculture".[2]

La Mésopotamie (du grec Μεσοποταμία / Mesopotamía, de μέσος / mésos, « entre, au milieu de », et ποταμός / potamós, « fleuves », littéralement le pays « entre les fleuves ») est une région historique du Moyen-Orient située entre le Tigre et l'Euphrate. Elle correspond pour sa plus grande part à l'Irak actuel.

Elle comprend deux régions topographiques distinctes : d'une part, au nord (nord-est de la Syrie et le nord de l'Irak actuel), une région de plateaux, celle-ci étant une zone de cultures pluviales et, d'autre part, au sud, une région de plaines où se pratique une agriculture reposant exclusivement sur l'irrigation.

L'ensemble des historiens et des archéologues contemporains s'accordent à dire que les Mésopotamiens sont à l'origine du premier système d'écriture créé vers 3400-3300 av. J.-C. Celui-ci évolua pour donner naissance à l'écriture « cunéiforme » (du latin cuneus, le « coin »).

Actuellement, le terme « Mésopotamie » est généralement utilisé en référence à l'histoire antique de cette région, pour la civilisation ayant occupé cet espace jusqu'aux derniers siècles avant l'ère chrétienne ou au VIIe siècle, plus exactement en 637 ap. J.-C. avec la conquête des Arabes musulmans.

La Mesopotamia (dal greco Μεσοποταμία/Mesopotamía, comp. di μέσος-/mésos- 'centrale, che sta in mezzo', ποταμός/potamós 'fiume' e il suff. -ia 'terra, landa, Paese'; cioè 'terra fra i fiumi Tigri ed Eufrate') denota una regione storica del Vicino Oriente, parte della cosiddetta Mezzaluna Fertile.

La Mesopotamia fu conquistata prima dai Sumeri, poi dagli Accadi, dai Gutei, dagli Amorrei (????????, Martu in sumerico), dai Babilonesi, dai Cassiti, dagli Assiri e dai Persiani.

Con il termine Mesopotamia i Greci intendevano la zona settentrionale che si estende tra il Tigri e l'Eufrate. Con il tempo l'uso di questa definizione divenne di più ampio respiro, fino a comprendere anche le zone limitrofe. Oggi possiamo impropriamente definirne i confini indicandoli con la catena dei monti Zagros a est, quella del Tauro a nord, steppe e deserti a ovest e sud-ovest e, infine, il Golfo Persico a sud (la zona paludosa dello Shatt al-'Arab). Nella suddivisione territoriale odierna corrisponde quindi ai territori dell'Iraq, e a parte di territori di Turchia, Siria, Iran, Arabia Saudita e Kuwait. La regione era considerata uno dei corni della mezzaluna fertile e vi si trovavano, allo stato selvatico, quelli che sarebbero diventati gli alimenti base della dieta dell'uomo nell'antichità: cereali, leguminose, ovini e bovini.

Foreste di tipo mediterraneo sulle montagne a nord ospitavano una flora di querce, pini, cedri e ginepri e una fauna di animali selvatici quali leopardi, leoni e cervi che ritroviamo anche nell'iconografia dell'arte giunta fino a noi. Da questa catena montuosa, il Tauro, parte il percorso dei due fiumi, molto importante per la popolazione. Difatti ha influito molto sulla vita e mentalità dei popoli che l'abitavano: sorgendo in una catena montuosa a clima mediterraneo, entrambi i fiumi erano soggetti a una portata variabile e a improvvise e disastrose inondazioni, tanto che nel corso dei millenni più volte hanno cambiato il corso del proprio letto. Proseguendo verso sud, i due fiumi si gettavano nel golfo con estuari separati ma, con il passare del tempo, costituirono la regione paludosa dello Shatt al-'Arab unendo il proprio percorso.

Mesopotamia (del Mesopotamia ‘tierra entre dos ríos’, árabe bilād al-rāfidayn, traducción del persa antiguo Miyanrudan ‘la tierra entre ríos’, o del siríaco ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪܝܢ beth nahrin ‘entre dos ríos’) es el nombre por el cual se conoce a la zona del Oriente Próximo ubicada entre los ríos Tigris y Éufrates, si bien se extiende a las zonas fértiles contiguas a la franja entre ambos ríos, y que coincide aproximadamente con las áreas no desérticas del actual Irak y la zona limítrofe del norte-este de Siria.

El término alude principalmente a esta zona en la Edad Antigua que se dividía en Asiria (al norte) y Babilonia (al sur). Babilonia (también conocida como Caldea), a su vez, se dividía en Acadia (parte alta) y Caldea (parte baja).1 Sus gobernantes eran llamados patesi.

Los nombres de ciudades como Ur o Nippur, de héroes legendarios como Gilgameš, del Código Hammurabi, de los asombrosos edificios conocidos como zigurats, provienen de la Mesopotamia Antigua. Y episodios mencionados en la Biblia o en la Torá, como los del diluvio universal o la leyenda de la Torre de Babel, aluden a hechos ocurridos en esta zona.

La historia de la Mesopotamia está dividida en 5 etapas: Periodo Sumerio, Imperio Acadio, Imperio Babilónico, Imperio Asirio e Imperio Neobabilónico.

El sistema social estaba ligado a la economía, por lo que no había castas ni estratificación, solo diferenciación en las posiciones económicas.

Месопота́мия (др.-греч. Μεσοποταμία; араб. الجزيرة, Эль-Джезира[1], или араб. ما بين النهرين, Ма-Байн-эн-Нахрайн[1]; арам. ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪܝܢ, тур. Mezopotamya) — историко-географический регион на Ближнем Востоке, расположенный в долине двух рек — Тигра и Евфрата, в зоне Плодородного полумесяца; место существования одной из древнейших цивилизаций в истории человечества. В научной литературе встречаются альтернативные обозначения региона — Двуречье и Междуречье, в которые вкладывается различный смысл.

Современные государства, включающие земли Месопотамии, — Ирак, северо-восточная Сирия, периферийно Турция и Иран.

纳斯卡巨画(西班牙语:Líneas de Nazca/ˈnæzkɑː/ ;奇楚瓦语:Naska siq'ikuna)是一组位于秘鲁南部塞丘拉沙漠上[1],在纳斯卡镇与帕尔帕市之间的巨大地面图形,它们是在公元前500年至公元500 年之间,由纳斯卡文明在沙漠地面上制造凹陷或浅切口、并去除鹅卵石留下不同颜色的泥土而创造的。纳斯卡巨画有两个主要阶段,从公元前400年到公元前200年完成的帕拉卡斯阶段[2] ,以从公元前200 年到公元500年的纳斯卡阶段。[3][4]

纳斯卡巨画在1939年由美国考古学家保罗·柯索发现。虽然有些地方的人体石刻是以帕拉卡作为主题。但实则有数以百计的个别图形,出自简单的线条,以复杂排列构成鱼类、螺旋形、藻类、兀鹫、蜘蛛、花、鬣蜥、鹭、手、树木、蜂鸟、猴子、猫等。学者们对这些设计的目的有不同的解释,但总言来说它们被认为具有宗教意义。[5][6][7][8] 并于1994年被指定为联合国教科文组织世界遗产。

纳斯卡巨画各个图形设计的宽度约在400到1100米间。所有线路的总长度超过1,300公里(800英里),占地面积约50公里(19平方英里)。纳斯卡巨画通常约10到15厘米深[9]。是通过去除表层红棕色氧化铁涂层的鹅卵石,并露出黄灰色底土制成的。由于地处偏远,加上当地高原较为干燥稳定的气候,使得纳斯卡巨画大多被自然保存下来。

Die Nazca-Linien, oft auch Nasca-Linien geschrieben, sind über 1500 riesige, nur aus der Luft und von umliegenden Hügeln aus sicht- und erkennbare Scharrbilder (Geoglyphen) in der Wüste bei Nazca und Palpa in Peru. Benannt sind die Linien, die Wüste und die Kultur nach der unweit der Ebene liegenden Stadt Nazca. Als Urheber der Linien gelten die Paracas-Kultur und die Nazca-Kultur. Die Nazca-Ebene zeigt auf einer Fläche von 500 km² schnurgerade, bis zu 20 km lange Linien, Dreiecke und trapezförmige Flächen sowie Figuren mit einer Größe von etwa zehn bis mehreren hundert Metern, z. B. Abbilder von Menschen, Affen, Vögeln und Walen. Oft sind die figurbildenden Linien nur wenige Zentimeter tief. Durch die enorme Größe sind sie nur aus großer Entfernung zu erkennen, von den Hügeln in der Umgebung oder aus Flugzeugen.[1]

Eine systematische Erkundung und Vermessung zusammen mit archäologischen Grabungen zwischen 2004 und 2009 im Umfeld und zum Teil in den Linien konnte ihre Entstehung und ihren Zweck mit hoher Wahrscheinlichkeit klären: Es handelt sich demnach um Gestaltungen im Rahmen von Fruchtbarkeitsritualen, die zwischen 800 v. Chr. und 600 n. Chr. angelegt und durch periodische Klimaschwankungen veranlasst wurden.[2][3] Die moderne Archäologie geht davon aus, dass die Nazca-Linien Aktionsflächen für Rituale in Hinblick auf Wasser und Fruchtbarkeit gewesen sind.

尼布甲尼撒二世(亚拉姆语:ܢܵܒܘܼ ܟܘܼܕܘܼܪܝܼ ܐܘܼܨܘܼܪ;希伯来语:נְבוּכַדְנֶצַּר Nəḇūḵaḏneṣṣar;古希腊语:Ναβουχοδονόσωρ;Naboukhodonósôr;阿拉伯语:نِبُوخَذنِصَّر nibūḫaḏniṣṣar;约前634年—前562年),是巴比伦迦勒底帝国的君主,在位时间约为前605年-前562年,知名于建成空中花园、毁坏所罗门圣殿。他曾征服犹大王国和耶路撒冷,并流放犹太人,《圣经列王纪》和《耶利米书》描述了他征服犹大王国的过程。[2]

他的名字意思是“保护继承者尼布”。

Nabū-kudurrī-uṣur II. oder Nebukadnezar II. (teils auch Nebukadnezzar[1]; sumerisch AG.NIG.DU-URU und PA.NIG.DU-PAP, spätbabylonisch Nabium-Kudurru-usur, aramäisch nbwkdsr „Nebukadser“, Altes Testament נְבוּכַדְרֶאצַּר [nəvūxadrɛt͡st͡sar] oder נְבוּכַדְנֶאצַּר [nəvūxadnɛt͡st͡sar], altgriechisch Ναβουχοδονόσωρ Nabouchodonósôr, lateinisch Nabuchodonosor, klassisch-arabisch بُخْت نَصَّر, DMG Buḫt Naṣṣar, modern-arabisch نبوخذنصر, DMG nibūḫaḏniṣṣar; * um 640 v. Chr.; † 562 v. Chr.) war von 605 bis 562 v. Chr. neubabylonischer König.

Nebukadnezars Name war offenbar programmatisch am Vorfahren Nebukadnezar I. orientiert und bedeutet „Der Gott Nabū schütze meinen ersten Sohn“. Die erste Anordnung als König stammt vom 7. September aus seinem Akzessionsjahr 605 v. Chr. Sein erstes Regierungsjahr begann 604 v. Chr. am 1. Nisannu. In seinem 43. Regierungsjahr ist für den 26. Ululu (8. Oktober 562 v. Chr.) in Uruk letztmals ein Dokument mit seinem Namen datiert.[2] Nebukadnezars Sohn Amēl-Marduk folgte ihm auf den Thron.

《奥德赛》(古希腊语:Ὀδύσσεια,转写:Odýsseia,英语:Odyssey)又译《奥狄赛》、《奥德修记》、或《奥德赛飘流记》是古希腊最重要的两部史诗之一(另一部是《伊利亚特》)。《奥德赛》延续了《伊利亚特》的故事情节,是盲诗人荷马所作。这部史诗是西方文学的奠基之作,是除《伊利亚特》外现存最古老的西方文学作品。一般认为,《奥德赛》创作于公元前8世纪末的爱奥尼亚,即今希腊安纳托利亚的沿海地区。

《奥德赛》主要讲述了希腊英雄奥德修斯(或译奥德赛斯,罗马神话中称为“尤利西斯”)在特洛伊陷落后返乡的故事。十年特洛依战争结束后,奥德修斯又漂泊了十年,才回到了故乡伊萨卡。人们认为他已经死去,而他的妻子珀涅罗珀和儿子忒勒玛科斯必须面对一群放肆的求婚者,这些人相互竞争,以求与珀涅罗珀成婚。

如今,《奥德赛》已被译为多国语言,是公认的世界文学经典。许多学者认为,这部史诗是由一些诗人、歌手或专业表演者口头创作而成的。至于当时口头表演的细节是什么样,这个故事是如何由口头诗歌变为书面著作,学者至今仍争论不休。《奥德赛》的用语是一种书面的诗话希腊语,混合了伊欧里斯语、爱奥尼亚语等多种希腊方言。全诗共有12110行,通篇使用六音步长短短格。不仅是战士们的行动,诗歌的非线性的叙事方法,以及妇人和农奴们对事件发展的影响,都是《奥德赛》里引人注目的元素。在英文及其他很多语言中,单词“奥德赛”(odyssey)现在用来指代一段史诗般的征程。

《奥德赛》的结尾已经丢失。但是还有一个失落的续集,忒勒戈诺斯史诗,据说是为斯巴达的修涅诵所著,而不是荷马。一种说法是被缪西斯或昔兰尼的犹哥蒙所藏。

『オデュッセイア』(古代ギリシア語イオニア方言:ΟΔΥΣΣΕΙΑ, Ὀδύσσεια, Odysseia, ラテン語:Odyssea)は、『イーリアス』とともに「詩人ホメーロスの作」として伝承された古代ギリシアの長編叙事詩[1]。

『イーリアス』の続編作品にあたり、そのため叙事詩環の一つに数えられることもある。長編叙事詩では、古代ギリシア文学最古期にあたる。

イタケーの王である英雄オデュッセウスがトロイア戦争の勝利の後に凱旋する途中に起きた、10年間にもおよぶ漂泊が語られ[1][2]、オデュッセウスの息子テーレマコスが父を探す探索の旅も展開される。不在中に妃のペーネロペー(ペネロペ)に求婚した男たちに対する報復なども語られる[1]。

紀元前8世紀頃に吟遊詩人が吟唱する作品として成立し、その作者はホメーロスと伝承されるが、紀元前6世紀頃から文字に書かれるようになり、現在の24巻からなる叙事詩に編集された。この文字化の事業は、伝承ではアテーナイのペリクレスに帰せられる。

古代ギリシアにおいては、ギリシア神話と同様に『オデュッセイア』と『イーリアス』は、教養ある市民が必ず知っているべき知識のひとつとされた。なお『イーリアス』と『オデュッセイア』が同一の作者によるものか否かは長年の議論があるところであり、一部の研究者によって、後者は前者よりも遅く成立し、かつそれぞれの編纂者が異なるとの想定がなされている(詳細はホメーロス問題を参照)。

The Odyssey (/ˈɒdəsi/;[1] Greek: Ὀδύσσεια Odýsseia, pronounced [o.dýs.sej.ja] in Classical Attic) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is, in part, a sequel to the Iliad, the other Homeric epic. The Odyssey is fundamental to the modern Western canon; it is the second-oldest extant work of Western literature, while the Iliad is the oldest. Scholars believe the Odyssey was composed near the end of the 8th century BC, somewhere in Ionia, the Greek coastal region of Anatolia.[2]

The poem mainly focuses on the Greek hero Odysseus (known as Ulysses in Roman myths), king of Ithaca, and his journey home after the fall of Troy. It takes Odysseus ten years to reach Ithaca after the ten-year Trojan War.[3] In his absence, it is assumed Odysseus has died, and his wife Penelope and son Telemachus must deal with a group of unruly suitors, the Mnesteres (Greek: Μνηστῆρες) or Proci, who compete for Penelope's hand in marriage.

The Odyssey continues to be read in the Homeric Greek and translated into modern languages around the world. Many scholars believe the original poem was composed in an oral tradition by an aoidos (epic poet/singer), perhaps a rhapsode (professional performer), and was more likely intended to be heard than read.[2] The details of the ancient oral performance and the story's conversion to a written work inspire continual debate among scholars. The Odyssey was written in a poetic dialect of Greek—a literary amalgam of Aeolic Greek, Ionic Greek, and other Ancient Greek dialects—and comprises 12,110 lines of dactylic hexameter.[4][5] Among the most noteworthy elements of the text are its non-linear plot, and the influence on events of choices made by women and slaves, besides the actions of fighting men. In the English language as well as many others, the word odyssey has come to refer to an epic voyage.

The Odyssey has a lost sequel, the Telegony, which was not written by Homer. It was usually attributed in antiquity to Cinaethon of Sparta. In one source,[which?] the Telegony was said to have been stolen from Musaeus of Athens by either Eugamon or Eugammon of Cyrene (see Cyclic poets).

L’Odyssée (en grec ancien Ὀδύσσεια / Odússeia) est une épopée grecque antique attribuée à l’aède Homèrenote 1, qui l'aurait composée après l’Iliade, vers la fin du VIIIe siècle av. J.-C. Elle est considérée comme l’un des plus grands chefs-d’œuvre de la littérature et, avec l’Iliade, comme l'un des deux « poèmes fondateurs » de la civilisation européenne.

L’Odyssée relate le retour chez lui du héros Ulysse, qui, après la guerre de Troie dans laquelle il a joué un rôle déterminant, met dix ans à revenir dans son île d'Ithaque, pour y retrouver son épouse Pénélope, qu'il délivre des prétendants, et son fils Télémaque. Au cours de son voyage sur mer, rendu périlleux par le courroux du dieu Poséidon, Ulysse rencontre de nombreux personnages mythologiques, comme la nymphe Calypso, la princesse Nausicaa, les Cyclopes, la magicienne Circé et les sirènes. L'épopée contient aussi un certain nombre d'épisodes qui complètent le récit de la guerre de Troie, par exemple la construction du cheval de Troie et la chute de la ville, qui ne sont pas évoquées dans l’Iliade. L’Odyssée compte douze mille cent neuf hexamètres dactyliques, répartis en vingt-quatre chants, et peut être divisée en trois grandes parties : la Télémachie (chants I-IV), les Récits d'Ulysse (chants V-XII) et la Vengeance d'Ulysse (chants XIII-XXIV)2,1.

L’Odyssée a inspiré un grand nombre d'œuvres littéraires et artistiques au cours des siècles, et le terme « odyssée » est devenu par antonomase un nom commun désignant un « récit de voyage plus ou moins mouvementé et rempli d'aventures singulières »3.

L'Odissea (in greco antico: Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia) è uno dei due grandi poemi epici greci attribuiti all'opera del poeta Omero. Narra delle vicende riguardanti l'eroe Odisseo (o Ulisse, con il nome latino), dopo la fine della Guerra di Troia, narrata nell'Iliade. Assieme a quest'ultima, rappresenta uno dei testi fondamentali della cultura classica occidentale e viene tuttora comunemente letto in tutto il mondo sia nella versione originale che nelle sue numerose traduzioni.

La Odisea (en griego: Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia) es un poema épico griego compuesto por 24 cantos, atribuido al poeta griego Homero. Se cree que fue compuesta en el siglo VIII a. C. en los asentamientos que tenía Grecia en la costa oeste del Asia Menor (actual Turquía asiática). Según otros autores, la Odisea se completa en el siglo VII a. C. a partir de poemas que sólo describían partes de la obra actual. Fue originalmente escrita en lo que se ha llamado dialecto homérico. Narra la vuelta a casa, tras la Guerra de Troya, del héroe griego Odiseo (al modo latino, Ulises: Ὀδυσσεὺς en griego; Vlixes en latín). Además de haber estado diez años fuera luchando, Odiseo tarda otros diez años en regresar a la isla de Ítaca, donde poseía el título de rey, período durante el cual su hijo Telémaco y su esposa Penélope han de tolerar en su palacio a los pretendientes que buscan desposarla (pues ya creían muerto a Odiseo), al mismo tiempo que consumen los bienes de la familia.

La mejor arma de Odiseo es su mētis o astucia. Gracias a su inteligencia —además de la ayuda provista por Palas Atenea, hija de Zeus Cronida— es capaz de escapar de los continuos problemas a los que ha de enfrentarse por designio de los dioses. Para esto, planea diversas artimañas, bien sean físicas —como pueden ser disfraces— o con audaces y engañosos discursos de los que se vale para conseguir sus objetivos.

El poema es, junto a la Ilíada, uno de los primeros textos de la épica grecolatina y por tanto de la literatura occidental. Se cree que el poema original fue transmitido por vía oral durante siglos por aedos que recitaban el poema de memoria, alterándolo consciente o inconscientemente. Era transmitido en dialectos de la Antigua Grecia. Ya en el siglo IX a. C., con la reciente aparición del alfabeto, tanto la Odisea como la Ilíada pudieron ser las primeras obras en ser transcritas, aunque la mayoría de la crítica se inclina por datarlas en el siglo VIII a. C. El texto homérico más antiguo que conocemos es la versión de Aristarco de Samotracia (siglo II a. C.). El poema está escrito usando una métrica llamada hexámetro dactílico. Cada línea de la Odisea original estaba formada por seis unidades o pies, siendo cada pie dáctilo o espondeo.1 Los primeros cinco pies eran dáctilos y el último podía ser un espondeo o bien un troqueo. Los distintos pies se separan por cesuras o pausas.

«Одиссе́я» (др.-греч. Ὀδύσσεια) — вторая после «Илиады» классическая поэма, приписываемая древнегреческому поэту Гомеру. Создана, вероятно, в VIII веке до н. э. или несколько позже. Рассказывает о приключениях мифического героя по имени Одиссей во время его возвращения на родину по окончании Троянской войны, а также о приключениях его жены Пенелопы, ожидавшей Одиссея на Итаке.

Как и другое знаменитое произведение Гомера, «Илиада», «Одиссея» изобилует мифическими элементами, которых здесь даже больше (встречи с циклопом Полифемом, волшебницей Киркой, богом Эолом и т. п.). Большинство приключений в поэме описывает сам Одиссей во время пира у царя Алкиноя.

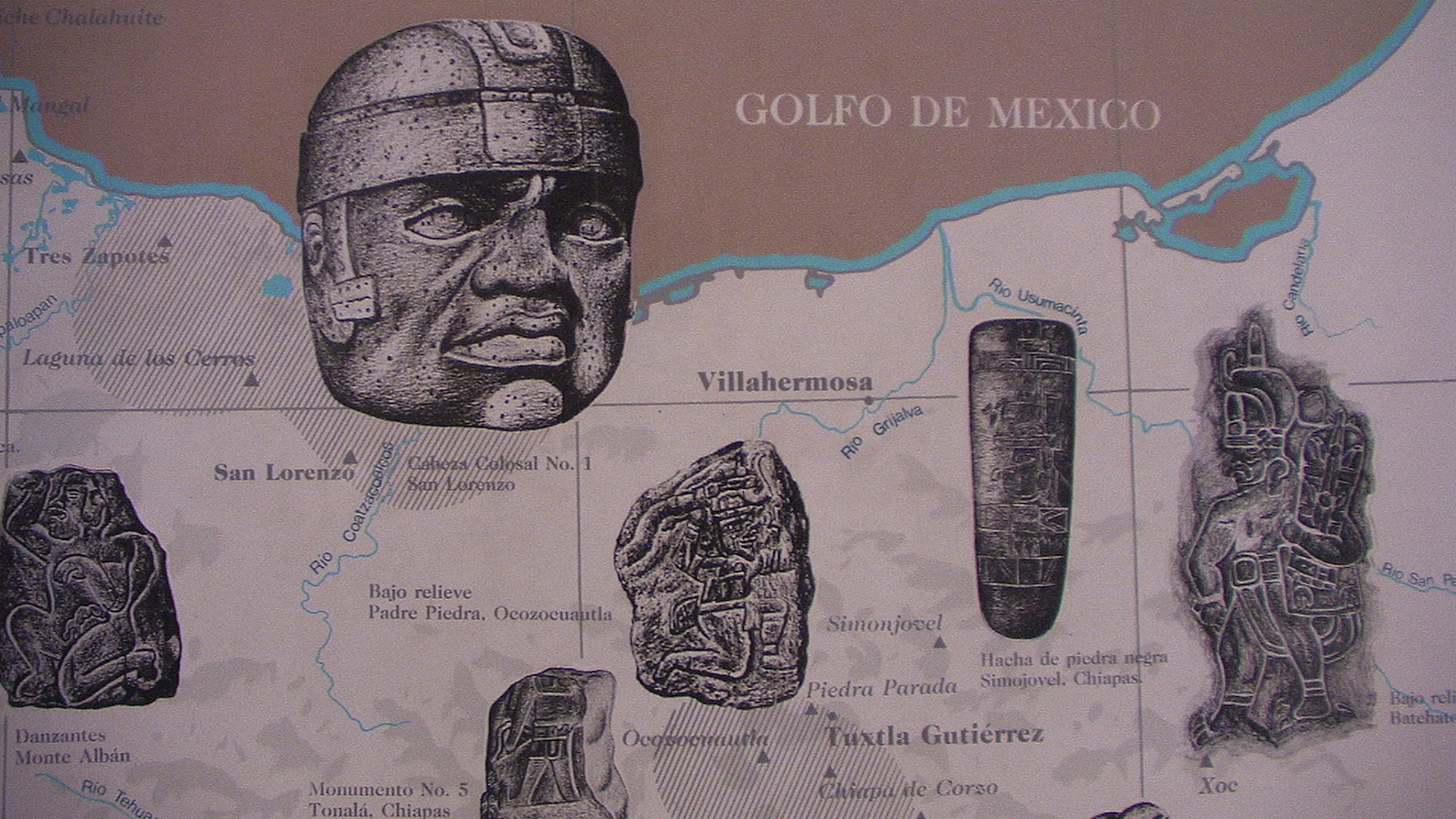

奥尔梅克文明(Olmec)是已知的最古老的美洲文明之一。它存在和繁盛于公元前1200年到公元前400年的中美洲(现在的墨西哥中南部)。

“奥尔梅克”一词源自纳瓦特尔语中用以指奥尔梅克人的单词Ōlmēcatl(发音:/oːlˈmeːkat͡ɬ/,此词在纳瓦特尔语中之众数形为Ōlmēcah,发音/oːlˈmeːkaʔ/),而在纳瓦特尔语中,此词为ōlli(意即“橡胶”,发音/ˈoːlːi/)和mēcatl(意即“人”,发音/ˈmeːkat͡ɬ/)的合成词,故Ōlmēcatl在纳瓦特尔语中的意思可解作“胶人”。

Als Olmeken (von Nahuatl Singular Ōlmēcatl beziehungsweise Plural Ōlmēcah für „Leute aus dem Kautschukland“) wurden von Archäologen die Träger der mittelamerikanischen La-Venta-Kultur bezeichnet. Ihre tatsächliche ethnische Zugehörigkeit ist unbekannt. Die Kultur der Olmeken ist von etwa 1500 bis um 400 v. Chr. entlang der Küste des Golfs von Mexiko nachweisbar. Ihre bekanntesten kulturellen Hinterlassenschaften sind mehrere Kolossalköpfe. Ob die Kultur der Olmeken als Proto-Maya-Kultur angesehen werden kann, wurde vielfach diskutiert, ist aber wegen des großen zeitlichen und räumlichen Abstands eher unwahrscheinlich.

オルメカ(Olmeca)は、紀元前1200年頃から紀元前後にかけ、先古典期のメソアメリカで栄えた文化・文明である[1]。アメリカ大陸で最も初期に生まれた文明であり、その後のメソアメリカ文明の母体となったことから、「母なる文明」と呼ばれる[2]。

オルメカとは、ナワトル語で「ゴムの国の人」を意味し、スペイン植民地時代にメキシコ湾岸の住民を指した言葉である。巨石や宝石を加工する技術を持ち、ジャガー信仰などの宗教性も有していた。その美術様式や宗教体系は、マヤ文明などの古典期メソアメリカ文明と共通するものがある。

オルメカの影響は中央アメリカの中部から南部に広がっていたが、支配下にあったのは中心地であるメキシコ湾岸地域に限られた[4]。その領域はベラクルス州南部からタバスコ州北部にかけての低地で、雨の多い熱帯気候のため、たびたび洪水が起こった。しかし、河川によって肥沃な土地が形成され、神殿を中心とした都市が築かれた[2]。

オルメカの文化は、出土するさまざまな石像に現れている。人間とジャガーを融合させた神像は、彼らにジャガーを信仰する風習があったことを物語っている[2]。祭祀場では儀式としての球技が行われ、その際には人間が生贄として捧げられた[4]。また、絵文字や数字を用い、ゼロの概念を持つなど、数学や暦が発達していた[2]。

The Olmecs (/ˈɒlmɛks, ˈoʊl-/) were the earliest known major civilization in Mesoamerica following a progressive development in Soconusco. They lived in the tropical lowlands of south-central Mexico, in the present-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco. It has been speculated that the Olmecs derive in part from neighboring Mokaya or Mixe–Zoque.

The Olmecs flourished during Mesoamerica's formative period, dating roughly from as early as 1500 BCE to about 400 BCE. Pre-Olmec cultures had flourished in the area since about 2500 BCE, but by 1600–1500 BCE, early Olmec culture had emerged, centered on the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán site near the coast in southeast Veracruz.[1] They were the first Mesoamerican civilization, and laid many of the foundations for the civilizations that followed.[2] Among other "firsts", the Olmec appeared to practice ritual bloodletting and played the Mesoamerican ballgame, hallmarks of nearly all subsequent Mesoamerican societies. The aspect of the Olmecs most familiar now is their artwork, particularly the aptly named "colossal heads".[3] The Olmec civilization was first defined through artifacts which collectors purchased on the pre-Columbian art market in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Olmec artworks are considered among ancient America's most striking.[4]

Les Olmèques sont un ancien peuple précolombien de Mésoamérique s'étant épanoui de 1200 av. J.-C. jusqu'à 500 av. J.-C. sur la côte du golfe du Mexique, dans le bassin de Mexico, et le long de la côte Pacifique (États du Guerrero, Oaxaca et Chiapas). Issu du terme nahuatl olmeca, qui signifie « les gens du pays du caoutchouc », ce mot est lié à la découverte de la première tête colossale olmèque, en 1862. Le terme « olmèque » a été officialisé en 1942 par les olmécologues.

Gli Olmechi erano un'antica civiltà precolombiana che viveva nell'area tropicale dell'odierno Messico centro-meridionale, approssimativamente negli stati messicani di Veracruz e Tabasco sull'Istmo di Tehuantepec. La civiltà olmeca fiorì durante il periodo formativo (pre-classico) mesoamericano (vedi Cronologie mesoamericane), estendentesi approssimativamente dal 1400 a.C. al 400 a.C. Gli Olmechi costituirono la prima civiltà mesoamericana e stabilirono le fondamenta delle culture successive. Esistono prove che gli Olmechi praticassero il sacrificio umano e praticassero un primitivo gioco con la palla (Giochi con la palla mesoamericani), caratteristiche di tutte le successive culture. L'influenza culturale olmeca fu molto ampia, tanto che opere d'arte di questa civiltà sono state trovate anche a El Salvador. Questo popolo ebbe il predominio nella sua area da circa il 1200 a circa il 400 a.C. e da molti è considerata la cultura madre di tutte le successive civiltà mesoamericane.

Il cuore del territorio olmeco (la cosiddetta area nucleare olmeca) è caratterizzato da pianure alluvionali, costellate da creste di basse colline e da vulcani. Le Montagne Tuxtlas vanno a nord, lungo la baia di Campeche. E fu proprio qui che gli olmechi costruirono complessi templari, fra cui San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, La Venta, Tres Zapotes, Laguna de los Cerros e La Mojarra. La loro influenza si estese dagli altopiani alla costa del Pacifico, vicino all'odierno Guatemala (come dimostrano i ritrovamenti di divinità olmeche).

Questa civiltà emerse e dominò tra il 1200 e il 400 a.C. e sembra che sia stata anche la prima civiltà mesoamericana a sviluppare un sistema di scrittura, anche se non ne sono ancora stati trovati esempi. Attualmente si dibatte se i simboli trovati nel 2002 e datati 650 a.C. siano o meno una forma di scrittura olmeca precedente a quella zapoteca, datata intorno al 500 a.C.[1] Ci sono anche altri geroglifici successivi, conosciuti come Epi-Olmechi, cioè post-olmechi: e se alcuni ritengono che questo epi-olmeco potrebbe essere una traslitterazione scritta che si colloca tra un precedente e sconosciuto sistema di scrittura olmeca e la scrittura dei maya, la questione resta comunque irrisolta e aperta.

Gli Olmechi sarebbero anche gli inventori del gioco della palla, che si diffuse anche nelle altre culture della regione con scopi sia ricreativi sia cerimoniali.

Attorno all'anno 1000 a.C. gli Olmechi, primi conoscitori della pianta di cacao, chiamavano il cacao kakawa; in seguito, esso fu rinominato kakaw dai Maya. [2]

Le caratteristiche e le tematiche della loro religione si svilupparono anche in seguito nelle altre culture dell'area. Stessa cosa accadde per la struttura fortemente gerarchica e verticistica delle loro città-stato.

La cultura olmeca fue la civilización que se desarrolló durante el periodo Preclásico de Mesoamérica. Aunque se han encontrado vestigios de su presencia en amplias zonas de Mesoamérica, se considera que el área nuclear olmeca —zona metropolitana— abarca la parte sureste del estado de Veracruz y el oeste de Tabasco. En ese sentido, es necesario hacer la aclaración de que el etnónimo olmeca les fue impuesto por los arqueólogos del siglo XX, y no debe ser confundido con el de los olmeca-xicalancas, que fueron un grupo que floreció en el epiclásico en sitios del centro de México, como Cacaxtla.

Durante mucho tiempo se consideró que la olmeca era la cultura madre de la civilización mesoamericana.1 Sin embargo, no está claro el proceso que dio origen al estilo artístico identificado con esta sociedad, ni hasta qué punto los rasgos culturales que se revelan en la evidencia arqueológica son creación de los olmecas del área nuclear. Se sabe, por ejemplo, que algunos de los atributos propiamente olmecas pudiesen haber aparecido, primero en Chiapas o en los Valles Centrales de Oaxaca. Entre otras dudas que están pendientes de respuesta definitiva, está la cuestión de los numerosos sitios asociados a esta cultura en la Depresión del Balsas (centro de Guerrero). Sea cual haya sido el origen de la cultura olmeca, la red de intercambios comerciales entre distintas zonas de Mesoamérica contribuyó a la difusión de muchos elementos culturales que son identificados con la cultura olmeca, incluidos el culto a las montañas y a las cuevas; el culto a la Serpiente Emplumada, como deidad asociada a la agricultura, el simbolismo religioso del jade e, incluso, el propio estilo artístico, que fue reelaborado intensamente en los siglos posteriores a la declinación de los principales centros de estos tiempos.

Ольме́ки — название племени, упоминающееся в ацтекских исторических хрониках. Название дано условно, по одному из небольших племен, живших на указанной ниже территории[1]. Создатели первой «крупной» цивилизации в Мексике, которая была наследницей культур, последовательно развивавшихся в Соконуско (на юго-западе мексиканского штата Чьяпас)[2]. Ольмеки обитали в тропических долинах южной и центральной Мексики на территории современных штатов Веракрус и Табаско. Возможно, родственны создателям культуры Мокая из Соконуско и носителям языков михе-соке.

Цивилизация ольмеков процветала в течение периода становления Мезоамерики примерно с 1500 до н. э. до 400 до н. э. Доольмекская культура существовала примерно с 2500 до н. э. по 1600-1500 до н. э. Ранние формы культуры ольмеков появились в районе Сан-Лоренсо-Теночтитлана неподалёку от побережья океана в юго-восточной части современного мексиканского штата Веракрус[3]. Во многих отношениях эта мезоамериканская цивилизация стала пионерской, повлияв на все последующие[4]. Например, ольмеки первыми ввели практику ритуального кровопролития и игру в мяч.

О цивилизации ольмеков стало известно в конце XIX — начале XX века, когда собиратели артефактов доколумбовой эпохи обнаружили на рынке казавшиеся необычными изделия. Сегодня ольмеки известны широкой публике прежде всего своими произведениями искусства, особенно гигантскими головами[5].

奥林匹亚宙斯神庙 (希腊语:Ναὸς τοῦ Ὀλυμπίου Διός, Naos tou Olympiou Dios), 又称Olympieion,是一座已毁的供奉宙斯的神庙,位于希腊首都雅典市中心,宪法广场以南700米,雅典卫城东南方500米。它始建于公元前6世纪,计划建成古代世界最伟大的寺庙,直到638年后,公元2世纪罗马帝国皇帝哈德良在位期间才得以完成。在罗马帝国时期,它是希腊最大的神庙,拥有古代世界最大的神像之一。

公元3世纪遭蛮族洗劫后,该庙被废弃。在罗马帝国灭亡后的数个世纪中,该庙的石料被大量取走,用于其他建筑的材料。今天仍可见到其遗迹,是雅典一个主要的旅游景点。

2007年1月21日,一群希腊多神教教徒在神庙举行崇拜宙斯的仪式。

Das Olympieion (auch Tempel des Olympischen Zeus) in Athen war einer der größten Tempel im antiken Griechenland. Der Bau geht auf das 6. Jahrhundert v. Chr. zurück, wurde aber erst unter dem römischen Kaiser Hadrian im 2. Jahrhundert n. Chr. vollendet. Das Olympieion befindet sich rund 500 m östlich der Akropolis.

The Temple of Olympian Zeus (Greek: Ναός του Ολυμπίου Διός, Naós tou Olympíou Diós), also known as the Olympieion or Columns of the Olympian Zeus, is a former colossal temple at the centre of the Greek capital Athens. It was dedicated to "Olympian" Zeus, a name originating from his position as head of the Olympian gods. Construction began in the 6th century BC during the rule of the Athenian tyrants, who envisaged building the greatest temple in the ancient world, but it was not completed until the reign of the Roman Emperor Hadrian in the 2nd century AD, some 638 years after the project had begun. During the Roman period the temple -that included 104 colossal columns- was renowned as the largest temple in Greece and housed one of the largest cult statues in the ancient world.

The temple's glory was short-lived, as it fell into disuse after being pillaged during a barbarian invasion in the 3rd century AD, just about a century after its completion. It was probably never repaired and was reduced to ruins thereafter. In the centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire, it was extensively quarried for building materials to supply building projects elsewhere in the city. Despite this, a substantial part of the temple remains today, notably sixteen of the original gigantic columns, and it continues to be part of a very important archaeological site of Greec.

L’Olympiéion (grec ancien : Ὀλυμπιεῖον), ou temple de Zeus olympien (grec ancien : Ναὸς τοῦ Ὀλυμπίου Διός), est situé au pied de l’Acropole d'Athènes. C’est un temple très vaste, d’ordre corinthien, dont il reste aujourd’hui 15 colonnes. Sa construction débuta au VIe siècle av. J.-C., et fut achevée par Hadrien en 131.

Il tempio di Zeus Olimpio (greco: Ναός του Ολυμπίου Διός) è un tempio situato ad Atene, in Grecia. Il tempio è situato a circa 500 metri dall'Acropoli e a circa 700 metri a sud del cuore di Atene, piazza Syntagma. Durante il periodo ellenistico ed il periodo romano è stato il tempio più grande della Grecia.

El templo de Zeus Olímpico, también conocido como el Olimpeion (griego Ναός του Ολυμπίου Διός, o Naos tou Olimpiou Dios), es un templo de Atenas. Aunque comenzado en el siglo VI a. C., no fue terminado hasta el reinado del emperador Adriano, en el siglo II. En las épocas helenística y romana era el templo más grande de Grecia.

ゼウス神殿またはオリュンピア=ゼウス神殿(ギリシア語: Ναὸς τοῦ Ὀλυμπίου Διός,ラテン語: Templum Iovis Olympii)は、ギリシャ、アテネのアクロポリスの東側にある神殿で、オリュンポス十二神の中の最高神であるゼウスに捧げられた神殿である。紀元前6世紀、僭主政のアテナイの時代に建設が始まったが、古代の世界で最大級であった神殿は完成させることがでなかった。神殿の完成は2世紀にローマ皇帝ハドリアヌスにより成し遂げられた。ローマ帝国期を通じて建てられた神殿の中で、この神殿は最大のものであった。

オリュンピア=ゼウス神殿またはオリュンピアのゼウス神殿の名前は、ハドリアヌスがつくらせた、金と象牙のゼウス像がオリュンピアのゼウス神殿にあったもののコピーであったことに由来する[1]。日本語でオリンピア=ゼウス神殿と表記されることもある。

L’Olympiéion (grec ancien : Ὀλυμπιεῖον), ou temple de Zeus olympien (grec ancien : Ναὸς τοῦ Ὀλυμπίου Διός), est situé au pied de l’Acropole d'Athènes. C’est un temple très vaste, d’ordre corinthien, dont il reste aujourd’hui 15 colonnes. Sa construction débuta au VIe siècle av. J.-C., et fut achevée par Hadrien en 131.

Le temple est situé au sud de l'Acropole, à environ 700 mètres du centre d'Athènes. Les fondations du premier temple remontent à -515, à l'époque de Pisistrate, mais le chantier s'est interrompu lorsque Hippias, fils de Pisistrate, fut ostracisé, en -510.

Durant la démocratie athénienne, le temple est resté inachevé, apparemment parce qu'il n'était pas dans l'esprit du temps de construire des bâtiments d'une telle ampleur. Dans sa Politique, Aristote le donne comme l'exemple de ce que les régimes tyranniques imposent inutilement à leurs populations. Les travaux ne reprennent qu'au IIIe siècle av. J.-C. avec la souveraineté macédonienne, et continuent sous le roi Antiochus IV Épiphane, qui charge l'architecte romain Decimus Cossutius de concevoir le plus grand temple du monde. Lorsque Antiochus meurt en -164, la construction du temple est à nouveau arrêtée.

En -86, Sylla, imposant à la Grèce la domination romaine, fit transporter au Capitole deux chapiteaux inachevés de l'Olympiéion, qui eurent une influence déterminante sur l'architecture romaine par l'adoption définitive de l'ordre corinthien dans toutes ses réalisations à venir.

Le temple ne fut achevé qu'en 129 (ou 131) apr. J.-C., sous l'impulsion de l'empereur Hadrien, grand admirateur de la culture grecque.

Il tempio di Zeus Olimpio (greco: Ναός του Ολυμπίου Διός) è un tempio situato ad Atene, in Grecia. Il tempio è situato a circa 500 metri dall'Acropoli e a circa 700 metri a sud del cuore di Atene, piazza Syntagma. Durante il periodo ellenistico ed il periodo romano è stato il tempio più grande della Grecia. Il tempio era costruito in marmo pentelico e misurava 108 metri in lunghezza e 41 in larghezza. Consisteva in 104 colonne corinzie, ognuna alta 17 metri. Solo 15 di queste colonne rimangono tuttora in piedi. La sedicesima colonna venne colpita da un fulmine durante un temporale nel 1852 e cadde sull'antica pavimentazione del tempio, dove è stata lasciata. Dell'imponente tempio rimangono, oltre alle colonne, il crepidoma e alcune porzioni dell'architrave tripartito.

El trabajo fue reanudado en 174 a. C., durante la dominación macedonia de Grecia, bajo el patrocinio del rey helenístico Antíoco IV Epífanes, que contrató al arquitecto romano Cosucio para diseñar el templo más grande del mundo conocido. Cuando Antíoco murió en 164 a. C. el trabajo estaba retrasado otra vez.1

En 86 a. C., después de que las ciudades griegas cayeran bajo dominio romano, el general Sila llevó dos columnas del templo inacabado a Roma, para adornar el templo de Júpiter Capitolino en la colina Capitolina. Estas columnas influyeron en el desarrollo del estilo corintio en Roma.

En el siglo II, el templo fue retomado por el emperador Adriano, un gran admirador de la cultura griega, quien finalmente lo llevó a su conclusión en 129 (algunas fuentes dicen que en 131).1

No se sabe cuando fue destruido el edificio pero, como muchos edificios grandes de Grecia, es probable que fuera destruido por un terremoto en la Edad Media. La mayor parte de sus ruinas se usaron como materiales de construcción.

Олимпейо́н, храм Зевса Олимпийского (греч. Ναός του Ολυμπίου Διός) — самый большой храм Греции, строившийся с VI века до н. э. до II века н. э.; располагается в Афинах в 500 метрах к юго-востоку от Акрополя и около 700 метров южнее площади Синтагма.

Согласно легенде храм был построен на месте святилища мифического Девкалиона, праотца греческого народа.

Возведение храма было начато в период тирании Писистрата, в 515 г. до н. э. Афинская демократия интересовалась храмом мало, Фемистокл использовал его части для оборонительной стены, связавшей Афины с Пиреем (её раскопанный участок виден рядом с храмом).

В 175—164 гг. до н. э. строительство храма Зевса (уже в коринфском ордере) продолжил царь эллинистической Сирии Антиох IV Эпифан. В 84 году до н. э. римский диктатор Сулла снял с колонн несколько резных капителей и употребил их для строительства храма его римского аналога, Юпитера Капитолийского. Несмотря на это Тит Ливий почти столетие спустя называет афинский храм Зевса «единственным на свете, достойным этого божества».

Завершён храм был только через 650 лет после начала строительства, при римском императоре Адриане, поклоннике греческой культуры. Освящение нового храма, который Адриан посвятил Зевсу Олимпийскому, было приурочено ко второму визиту императора в Афины и стало центральным пунктом программы Всегреческих празднеств 132 г.

Храм был сильно повреждён во время нашествия герулов в 267 г. и едва ли восстанавливался после этого. После того как Феодосий запретил почитание языческих богов, элементы храма были использованы при строительстве церквей и домов.

В настоящее время от храма уцелел один угол, состоящий из 14 колонн, увенчанных коринфскими капителями, 2 отдельностоящие колонны и одна поваленная.

Ostia Antica ist das Ausgrabungsgelände der antiken Stadt Ostia, der ursprünglichen Hafenstadt des antiken Rom und möglicherweise dessen erster Kolonie.

Der Name Ostia leitet sich von lateinisch ostium „Eingang; Mündung“ ab, womit die Tibermündung gemeint ist. Der Name Ostia Antica (Altes Ostia) wird zur Unterscheidung vom in den 1920er Jahren neugegründeten Stadtteil Ostia verwendet. Der nordöstlich anschließende moderne Stadtteil wird nach den Ausgrabungen ebenfalls Ostia Antica genannt.

奥斯提亚安提卡(意大利语:Ostia Antica)即古奥斯提亚。是位于意大利中部拉齐奥大区罗马市奥斯提亚的一座古罗马时期的港湾都市遗迹。由于砂石堆积,现在奥斯提亚安提卡距离海岸线已有3公里。在神话记载中,这里在公元前7世纪时就已经有城市[1]。但按照实际考古记录,这座城市的历史可以追溯至公元前4世纪初期。在公元前3世纪至2世纪时,这里曾是罗马海军的主要据点。2世纪时,城市发展达到鼎盛时期。

History

History

History

History

E 2500 - 2000 BC

E 2500 - 2000 BC

History

History

F 2000 - 1500 BC

F 2000 - 1500 BC

History

History

G 1500 - 1000 BC

G 1500 - 1000 BC

History

History

H 1000 - 500 BC

H 1000 - 500 BC

History

History

I 500 - 0 BC

I 500 - 0 BC

History

History

J 0 - 500 AD

J 0 - 500 AD

Syria

Syria

World Heritage

World Heritage

Civilization

Civilization

Palmyra (arabisch تدمر Tadmur; aramäisch ܬܕܡܘܪܬܐ Tedmurtā; hebräisch תדמור Tadmor), gegenwärtig auch Tadmor genannt, ist eine antike Oasenstadt im heutigen Gouvernement Homs in Syrien. Sie liegt auf dem Gebiet der modernen Stadt Tadmor, die vor dem Bürgerkrieg etwa 51.000 Einwohner hatte.

Die ersten archäologischen Funde stammten aus der Jungsteinzeit. Die erste schriftliche Erwähnung der Stadt selbst erfolgte in altorientalischer Zeit: Sie wurde in den Annalen mehrerer assyrischer Könige und im Alten Testament erwähnt. Palmyra war später Teil des Seleukidenreiches und erlebte seine Blütezeit nach der Annexion durch das Römische Reich im 1. Jahrhundert n. Chr.

Palmyra verfügte über eine gewisse Autonomie innerhalb des Römischen Reiches und wurde Teil der Provinz Syria. Die Metropole besaß einen eigenen Senat, der für öffentliche Arbeiten und die lokale Miliz zuständig war, und ein unabhängiges Steuersystem. Im 3. Jahrhundert wurde sie zur colonia erhoben. In der Zeit der Reichskrise des 3. Jahrhunderts gewann die Stadt stark an politischer Bedeutung und wurde 270 kurzzeitig unabhängig. Das Reich der Stadt stellte einen bedeutenden Machtfaktor im Vorderen Orient dar. Palmyra wurde jedoch 272 von römischen Truppen wieder erobert und die Stadt 273 nach einer gescheiterten zweiten Rebellion weitgehend zerstört.

Palmyra lag an einer wichtigen Karawanenstraße in Syrien, auf halber Strecke von Damaskus über die römische Oase Al-Dumair und weiter über das Kastell Resafa bis zum Euphrat. Inmitten der syrischen Wüste spenden zwei Quellen Wasser, mit dem die noch immer erhaltenen Palmengärten im Süden und Osten der Stadt bewässert werden. Der Reichtum der Stadt ermöglichte die Errichtung von monumentalen Bauprojekten. Im dritten Jahrhundert war die Stadt eine wohlhabende Metropole und zu einem regionalen Zentrum des Nahen Ostens aufgestiegen. Die Palmyrer gehörten zu den renommierten Händlern, etablierten Stationen entlang der Seidenstraße und betrieben im gesamten Reich Handel. Die Sozialstruktur der Stadt war tribal und ihre Bewohner sprachen mit dem Palmyrenischen Dialekt des Aramäischen eine eigene Sprache. Griechisch wurde für kommerzielle und diplomatische Zwecke verwendet. Die Kultur von Palmyra, die durch die Römer, Griechen und Perser beeinflusst wurde, ist in der Region einzigartig. Die Einwohner verehrten lokale Gottheiten und mesopotamische und arabische Götter.

Palmyra (/ˌpɑːlˈmaɪrə/; Palmyrene: ![]() Tadmor; Arabic: تَدْمُر Tadmur) is an ancient Semitic city in present-day Homs Governorate, Syria. Archaeological finds date back to the Neolithic period, and documents first mention the city in the early second millennium BC. Palmyra changed hands on a number of occasions between different empires before becoming a subject of the Roman Empire in the first century AD.

Tadmor; Arabic: تَدْمُر Tadmur) is an ancient Semitic city in present-day Homs Governorate, Syria. Archaeological finds date back to the Neolithic period, and documents first mention the city in the early second millennium BC. Palmyra changed hands on a number of occasions between different empires before becoming a subject of the Roman Empire in the first century AD.

The city grew wealthy from trade caravans; the Palmyrenes became renowned as merchants who established colonies along the Silk Road and operated throughout the Roman Empire. Palmyra's wealth enabled the construction of monumental projects, such as the Great Colonnade, the Temple of Bel, and the distinctive tower tombs. Ethnically, the Palmyrenes combined elements of Amorites, Arameans, and Arabs. The city's social structure was tribal, and its inhabitants spoke Palmyrene (a dialect of Aramaic), while using Greek for commercial and diplomatic purposes. Greco-Roman culture influenced the culture of Palmyra, which produced distinctive art and architecture that combined eastern and western traditions. The city's inhabitants worshiped local Semitic deities, Mesopotamian and Arab gods.

By the third century AD Palmyra had become a prosperous regional center. It reached the apex of its power in the 260s, when the Palmyrene King Odaenathus defeated Persian Emperor Shapur I. The king was succeeded by regent Queen Zenobia, who rebelled against Rome and established the Palmyrene Empire. In 273, Roman emperor Aurelian destroyed the city, which was later restored by Diocletian at a reduced size. The Palmyrenes converted to Christianity during the fourth century and to Islam in the centuries following the conquest by the 7th-century Rashidun Caliphate, after which the Palmyrene and Greek languages were replaced by Arabic.

Before AD 273, Palmyra enjoyed autonomy and was attached to the Roman province of Syria, having its political organization influenced by the Greek city-state model during the first two centuries AD. The city became a Roman colonia during the third century, leading to the incorporation of Roman governing institutions, before becoming a monarchy in 260. Following its destruction in 273, Palmyra became a minor center under the Byzantines and later empires. Its destruction by the Timurids in 1400 reduced it to a small village. Under French Mandatory rule in 1932, the inhabitants were moved into the new village of Tadmur, and the ancient site became available for excavations.

Palmyre (Παλμύρα / Palmúra en grec ancien, تدمر / tadmor en arabe) est une oasis du désert de Syrie, à 210 km au nord-est de Damas, où se situe un site historique très riche en ruines archéologiques, et la ville moderne de Tadmor.

Le site est classé patrimoine mondial de l'UNESCO depuis 1980, puis classé « en péril » pendant la guerre civile syrienne.

Palmira (in palmireno ![]() ; in arabo: تدمر), chiamata anche la Sposa del Deserto, fu in tempi antichi una delle più importanti città della Siria.

; in arabo: تدمر), chiamata anche la Sposa del Deserto, fu in tempi antichi una delle più importanti città della Siria.

Palmira (en árabe تدمر Tadmor1 o Tadmir) fue una antigua ciudad situada en el desierto de Siria, en la actual provincia de Homs a 3 km de la moderna ciudad de Tedmor2 o Tadmir, (versión árabe de la misma palabra aramea "palmira", que significa "ciudad de los árboles de dátil"). En la actualidad sólo persisten sus amplias ruinas que son foco de una abundante actividad turística internacional. La antigua Palmira fue la capital del Imperio de Palmira bajo el efímero reinado de la reina Zenobia, entre los años 268 - 272.

Palmira fue elegida como Patrimonio de la Humanidad en 1980. El 20 de junio de 2013, la Unesco incluyó a todos los sitios sirios en la lista del Patrimonio de la Humanidad en peligro para alertar sobre los riesgos a los que están expuestos debido a la Guerra Civil Siria.3

泛希腊运动会是古希腊举行的四场运动会的合称。四场运动会中最古老的是奥林匹克运动会,最早举办于公元前776年。泛希腊运动会的举行十分规律,是希腊人计算时间的方法之一。运动员来自希腊各地,甚至包括从小亚细亚到西班牙的古希腊殖民地,非希腊人和女性不允许参赛。主要赛事有战车赛、摔跤、拳击、五项全能等。比赛胜利者的唯一奖品是一个花冠,没有其他任何金钱或实物奖励。[1] 但赢得比赛者会为其城邦赢得荣誉。

Die Panhellenischen Spiele (griechisch πανελλήνιοι ἀγῶνες maskulin Plural) waren gesamtgriechische Wettkämpfe zu Ehren der griechischen Götter, die an religiösen Kultstätten abgehalten wurden. Ursprünglich handelte es sich um Wettkämpfe unter Kriegern in voller Kriegsmontur. Später wurde mit Ausnahme des Waffenlaufs die Rüstung abgelegt und die Kämpfer traten nackt an. Im Rahmen der religiös-sportlichen Veranstaltung wurden auch kulturelle Wettkämpfe im Dichten und Musizieren ausgetragen.

Zu den panhellenischen Spielen werden die überregionalen Wettkämpfe an vier Kultstätten gezählt: Olympia, Delphi, Korinth und Nemea. Die Sieger aus diesen Wettkämpfen erhielten jeweils ortsspezifische Kränze, Zweige oder Stängel. Der Austragungsmodus dieser Spiele fand meist im Vierjahres-, seltener auch im Zweijahresrhythmus statt. Dieser Rhythmus wurde Periodos (Umlauf, Wiederkehr) genannt. Ein Wettkämpfer, der während einer Olympiade (Vierjahreszyklus) in einer Sportart in allen vier Hauptkampfstätten siegte, erhielt den Titel Periodonike.

"Panhellenic Games" is the collective term for four separate sports festivals held in ancient Greece. The four Games were:

The Olympiad was one of the ways the Greeks measured time. The Olympic Games were used as a starting point, year one of the cycle; the Nemean and Isthmian Games were both held (in different months) in year two, followed by the Pythian Games in year three, and then the Nemean and Isthmian Games again in year four. The cycle then repeated itself with the Olympic Games. They were structured this way so that individual athletes could participate in all of the games.

(But note that the dial on the Antikythera mechanism – [1] – seems to show that the Nemean and Isthmian Games did not occur in the same years.)

Participants could come from all over the Greek world, including the various Greek colonies from Asia Minor to Spain. However, participants probably had to be fairly wealthy in order to pay for training, transportation, lodging, and other expenses. Neither women nor non-Greeks were allowed to participate, except for very occasional later exceptions, such as the Roman emperor Nero.

The main events at each of the games were chariot racing, wrestling, boxing, pankration, stadion and various other foot races, and the pentathlon (made up of wrestling, stadion, long jump, javelin throw, and discus throw). Except for the chariot race, all the events were performed nude.

The Olympic Games were the oldest of the four, said to have begun in 776 BC. It is more likely though that they were founded sometime in the late 7th century BC. They lasted until the Roman Emperor Theodosius, a Christian, abolished them as heathen in AD 393. The Pythian, Nemean and Isthmian games most likely began sometime in the first or second quarter of the 6th century BC. The Isthmian games were held at the temple to Poseidon on the Isthmus of Corinth.

The games are also known as the stephanitic games, because winners received only a garland for victory. (Stephanitic derives from stephanos the Attic Greek word for crown.) No financial or material prizes were awarded, unlike at other ancient Greek athletic or artistic contests, such as the Panathenaic Games, at which winners were awarded many amphorae of first-class Athenian olive-oil. The Olympic games awarded a garland of olives; the Pythian games, a garland of laurel, i.e. bay leaves; the Nemean games, a crown of wild celery, and the Isthmian, a garland of pine leaves in the archaic period, one of dried celery in the Classical and Hellenistic periods, and again one of pine from then on.[1] Though victors received no material awards at the games, they were often showered with gifts and honors on returning to their polis.

Les Jeux panhelléniques sont des fêtes à caractère religieux célébrées en Grèce antique en l'honneur des dieux, auxquels on participait de toutes les régions de Grèce. Ce sont à l'origine des concours athlétiques réservés à l'aristocratie, dont les familles disposaient d'assez de temps et d'argent pour s'entraîner de façon prolongée, et qui attachaient une importance primordiale aux prouesses athlétiques1 ; par la suite, ces compétitions cessèrent d'être l'apanage exclusif de la noblesse, et des jeunes gens issus de la bourgeoisie y remportèrent aussi des victoires ; à partir du Ve siècle av. J.-C., d'autres disciplines culturelles se sont ajoutées aux épreuves athlétiques, puis les athlètes devinrent des professionnels.

I Giochi Panellenici ("di tutti i greci") erano competizioni sportive a carattere sacro che impegnavano tutte le città dell'Ellade (Grecia); una di esse, i Giochi Olimpici, ha dato ispirazione ai giochi olimpici moderni.

Giochi Panellenici è un termine collettivo con cui si indicano quattro diverse manifestazioni sportive che si tenevano nell'antica Grecia. I quattro eventi erano:

- I Giochi olimpici - i giochi più importanti e prestigiosi, si tenevano ogni quattro anni ad Olimpia nell'Elide ed erano dedicati a Zeus.

- I Giochi pitici - si tenevano ogni quattro anni nei pressi di Delfi ed erano dedicati ad Apollo.

- I Giochi nemei - si tenevano ogni due anni a Nemea ed erano anch'essi dedicati a Zeus.

- I Giochi istmici - si tenevano ogni due anni nei pressi di Corinto ed erano dedicati a Poseidone.

I giochi venivano organizzati seguendo un ciclo di quattro anni, noto come Olimpiade, che era uno dei modi in cui gli antichi Greci misuravano il tempo. I Giochi Olimpici venivano presi come punto di partenza, ovvero rappresentavano il primo anno del ciclo; nel secondo anno si tenevano sia i Giochi Nemei che i Giochi Istmici (in mesi diversi), seguiti dai Giochi Pitici nel terzo anno e da una nuova edizione dei Nemei e Istmici nel quarto. A quel punto il ciclo ricominciava con la disputa dei Giochi Olimpici. Erano organizzati in questo modo affinché gli atleti potessero partecipare a tutti i giochi.

Nel 262 a.C. vennero aggiunti i giochi tolemaici a seguito della guerra cremonidea in funzione anti-macedone; questi giochi si tenevano ogni quattro anni ad Alessandria ed erano dedicati a Tolomeo Sotere e Berenice I.[1]

Juegos Panhelénicos es el término que recibe el conjunto de cuatro contiendas diferentes que eran celebradas en la antigua Grecia. Estos cuatro juegos eran los Juegos Olímpicos, los Juegos Píticos, los Juegos Nemeos y los Juegos Ístmicos.

Los Juegos Olímpicos eran los más importantes y prestigiosos, celebrados cada cuatro años cerca de Elis, en honor a Zeus. Los Juegos Píticos también eran celebrados cada cuatro años cerca de Delfos, en honor a Apolo. Los Juegos Nemeos, cada dos años, se celebraban en honor a Zeus en Nemea, aunque en determinadas épocas pasaron a ser realizados en Argos. Los Juegos Ístmicos, en honor a Poseidón, se celebraban en Corinto cada cuatro años.

Los Juegos eran celebrados cada ciclo de cuatro años conocido como Olimpiada, que era una de las medidas de tiempo de la antigua Grecia. En este ciclo, los primeros en celebrarse eran los Juegos Olímpicos que se efectuaban en el primer año; durante el segundo año se celebraban los Juegos Nemeos y los Juegos Ístmicos (en meses diferentes); durante el tercer año acontecían los Juegos Píticos; y en el cuarto año eran nuevamente celebrados los Juegos Nemeos y los Juegos Ístmicos. Después el ciclo se volvía a repetir comenzando nuevamente con los Juegos Olímpicos. Así, los Juegos estaban organizados de forma que un atleta pudiese participar en todos ellos.

Los participantes podían proceder de todo el mundo griego, incluyendo las colonias griegas que se extendían desde Anatolia hasta el Mediterráneo occidental. Sin embargo, los participantes probablemente tenían que ser bastante ricos para poder pagar el entrenamiento, el transporte, el alojamiento y otros costos. Además, no se permitía la participación a las mujeres ni a los no griegos excepto en excepciones muy ocasionales, como con Nerón.

Los principales acontecimientos de cada uno de los juegos fueron las carreras de carros, la lucha olímpica, el boxeo, el pancracio, el stadion junto a otras carreras a pie, y el pentatlón (compuesto por la lucha, el stadion, el salto de longitud, el lanzamiento de jabalina y el lanzamiento de disco). A excepción de las carreras de carros, en el resto de acontecimientos los participantes iban desnudos.

La historia escrita de los Juegos Olímpicos se remonta al 776 a. C., pero realmente se fundó varios siglos antes.[cita requerida] Los otros tres juegos se fundaron en el siglo VI a. C.

Панэллинские игры — общенациональные празднества (греч. πανήγυριν[1], ср. панегирик) в Древней Греции[2], устраивавшиеся в честь богов. Они возникли как спортивные состязания, к которым впоследствии добавились и другие дисциплины.

Первоначально панэллинские игры состояли из следующих этапов, так называемых «периодов»:

- Олимпийские игры — наиболее значимые соревнования, проводившиеся один раз в четыре года в Олимпии в честь бога Зевса. Победители-олимпионики награждались венками из веток оливкового дерева[3].

- Пифийские игры — проводились один раз в четыре года в Дельфах в честь бога Аполлона. Победители награждались лавровыми венками, так как лавр считался священным деревом Аполлона[4].

- Истмийские игры — проводились один раз в два года вблизи Коринфа и посвящались богу Посейдону. Победителям вручали пальмовую ветвь и венок, который в древнейшее и в императорское время плелся из сосновых ветвей, а в классическую эпоху — из сельдерея[5].

- Немейские игры — проводились один раз в два года близ Немеи в честь бога Зевса. Наградой для победителей служили венки из веток оливы или из сельдерея[6].

Атлеты, победившие во всех четырёх панэллинских играх, получали почётный титул периодоника[2].

В эпоху эллинизма панэллинскими играми стали также называть состязания не общегреческого, а местного значения[2].

帕拉卡斯文化(英语: Paracas culture),以帕拉卡斯半岛为中心的文化,即今秘鲁南部伊卡大区附近,[1]其年代约为公元前900—约公元400年。它的初期与查文文化关系密切,早期陶器制造拙劣,有时完成后加以彩绘。[2]至中期(约公元1年—约公元400年)其制陶技术有所提高,出土有精美的刺绣织物和工艺品,织物的多彩图案揭示该文化与纳斯卡文化存在联系

Die südamerikanische Paracas-Kultur existierte von 900 bis 200 v. Chr. Funde dieser Kultur wurden auf der Halbinsel Paracas an der Südküste Perus erstmals 1925 von dem peruanischen Archäologen Julio Tello entdeckt. Das wüstenartige Klima der Halbinsel bot günstigste Bedingungen für den Erhalt organischer Materialien. Dadurch sind kunstvoll gewebte Stoffe und die in ihnen eingewickelten Mumien in den Schachtgräbern der Fundorte Cavernas und Necropolis gefunden worden.

Die Mumien weisen Trepanationen und auffallende Schädeldeformationen auf.[1] Solche künstlichen Deformationen waren in verschiedenen Kulturen Südamerika verbreitet, um Stammeszugehörigkeiten sichtbar zu machen. Die Paracas-Kultur brachte es darin zu einiger Perfektion. Nachweisbar sind drei Grundformen: beidseitig abgeplattet, konisch und zylindrisch.[2]

Die Keramik der Paracas-Kultur war polychrom und trug Züge einer individuell gefertigten Produktion. In ihr zeigten sich Einflüsse aus Chavín de Huántar. Paracas selbst beeinflusste stark die Nazca-Kultur. Zu den Bedeutendsten Konstruktionen der Paracas-Kultur gehören die Nazca-Linien.

Financial

Financial

Historical coins, banknotes

Historical coins, banknotes

Literature

Literature

Architecture

Architecture

Lazio

Lazio

Review

Review

Sport

Sport