Deutsch-Chinesische Enzyklopädie, 德汉百科

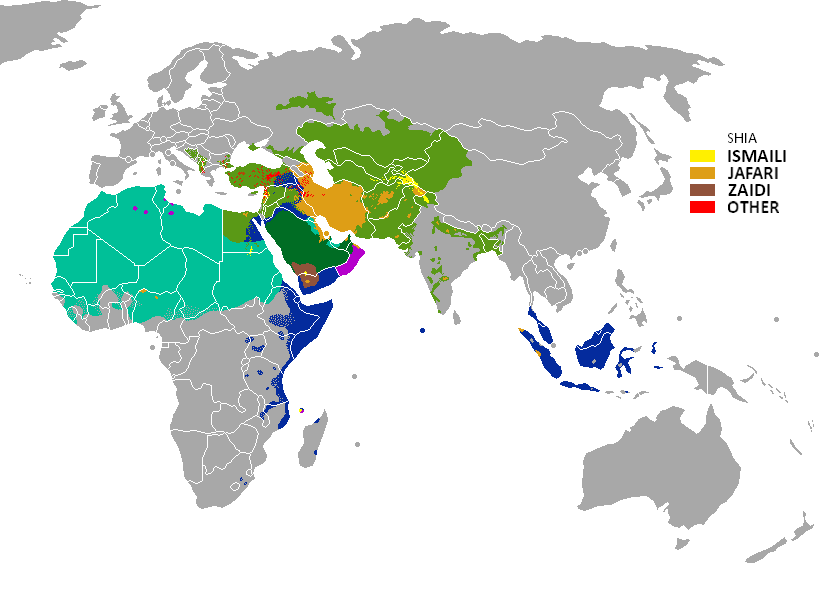

什叶派(阿拉伯语:شيعة,Shīʿah,英语:Shia,/ˈʃiːə/),来自阿拉伯语:شيعة علي(Shīʻatu ʻAlī,Shia-ne-Ali)的缩写,原意为阿里的追随者,与逊尼派并列为伊斯兰教的两大主要教派之一。什叶派与逊尼派各门派中的主要不同不在于教义问题,主要在于谁是穆罕默德“真正接班人”。在历史上曾出现过“穆阿维耶什叶”、“奥斯曼什叶”和“阿里什叶”等,目前则专指认为穆罕默德的继任者是阿里·本·阿比·塔利卜(穆罕默德堂弟及女婿)的人,逊尼派则认为穆罕默德的继任者是他的岳父阿布·伯克尔。

Die Schia (arabisch الشيعة asch-schīʿa, DMG aš-šīʿa ‚Anhängerschaft, Partei, Gruppe‘), im Deutschen auch Schiitentum oder Schiismus genannt, ist nach dem Sunnitentum die zweitgrößte religiöse Strömung innerhalb des Islams. Heute wird der Begriff häufig in verallgemeinernder Weise für die Zwölferschia verwendet, die die zahlenmäßig größte Gruppe innerhalb der Schia darstellt, allerdings umfasst die Schia noch zahlreiche andere Gruppierungen.

シーア派(アラビア語:الشيعة、ラテン文字転写:ash-Shīʻa(h))は、イスラム教の二大宗派の一つで、2番目の勢力を持つ。最大勢力であるもう一方はスンナ派(スンニ派)である。

7世紀のカリフであったアリー[1]とその子孫のみが、預言者の代理たる資格を持ち、「イスラム共同体(ウンマ))」の「指導者(イマーム)」の職務を後継する権利を持つと主張する。

Shia Islam or Shi'ism is one of the two main branches of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib as his successor and the Imam (leader) after him,[1] most notably at the event of Ghadir Khumm, but was prevented from the caliphate as a result of the incident of Saqifah. This view primarily contrasts with that of Sunni Islam, whose adherents believe that Muhammad did not appoint a successor and consider Abu Bakr, who was appointed caliph by a group of Muslims at Saqifah, to be the first rightful caliph after Muhammad.[2] A person observing Shia Islam is called a Shi'ite.

Shia Islam is based on Muhammad's hadith (Ghadir Khumm).[3][4] Shia consider Ali to have been divinely appointed as the successor to Muhammad, and as the first Imam. The Shia also extend this Imammah to Muhammad's family, the Ahl al-Bayt ("the people/family of the House"),[5] and some individuals among his descendants, known as Imams, who they believe possess special spiritual and political authority over the community, infallibility and other divinely ordained traits.[6] Although there are many Shia subsects, modern Shia Islam has been divided into two main groupings: Twelvers and Ismailis, with Twelver Shia being the largest and most influential group among Shia.[7][8][9]

Il regroupe environ 10 à 15 % des musulmans. La première communauté chiite vit en Iran, où elle constitue 90 % de la population du pays, et environ 40 % de la population chiite mondiale2,3,4. Le reste des musulmans chiites se répartit principalement en Irak, en Azerbaïdjan, au Pakistan, en Inde, à Bahreïn et au Liban.

L’Islam sciita (in arabo: شيعة, shiʿa «partito, fazione», sottinteso «di ʿAli e dei suoi discendenti») è il principale ramo minoritario dell'Islam (intorno al 15% ai primi del XXI secolo).

Se da un lato essa presenta la maggioranza della popolazione in Iran, Iraq, Azerbaigian e Bahrein, dall'altro in Libano e in Yemen essa costituisce una forte e significativa minoranza, con quasi un terzo della popolazione di fede sciita.

In Egitto invece, in Siria, in Turchia, in Afghanistan, in India, in Qatar, in Kuwait, in Pakistan, nell'Asia Centrale ex-sovietica, nell'Africa islamica a sud del Sahara, lo sciismo vanta percentuali assai minori (tra il 5% e il 10%), come è il caso della stessa Arabia Saudita, col suo scarso 4-5% all'incirca. Anche all'interno dello sciismo (come nel sunnismo e nel kharigismo) ci sono i sufi e coloro che rifiutano l'approccio sufico considerato troppo libero.

El chiismo o islam chií (o chía, en árabe, شيعة (šīʿa)) constituye una de las principales ramas del islam junto al sunismo. Es el nombre tradicional por el que se conoce a la escuela de jurisprudencia islámica Ya'farita. El chiismo es profesado por alrededor del 15 % de los 1600 millones de musulmanes existentes en el mundo.2

Шии́ты (араб. شيعة; [шӣ‘а] — приверженцы, последователи) — направление ислама, объединяющее различные общины, признавшие Али ибн Абу Талиба и его потомков единственно законными наследниками и духовными преемниками пророка Мухаммеда[1]. В узком смысле понятие, как правило, означает шиитов-двунадесятников, преобладающее направление в шиизме, которое преимущественно распространено в Иране, Азербайджане, Бахрейне, Ираке и Ливане, а также в Йемене, Афганистане, Турции, Сирии, Кувейте, Пакистане, ОАЭ.

Shintō (jap. 神道, wird im Deutschen meist übersetzt mit „Weg der Götter“) – auch als Shintoismus bezeichnet – ist die ethnische Religion der Japaner (siehe auch Religion in Japan). Shintō und Buddhismus, die beiden in Japan bedeutendsten Religionen, sind aufgrund ihrer langen gemeinsamen Geschichte nicht immer leicht zu unterscheiden. Als wichtigstes Merkmal, das die beiden religiösen Systeme trennt, wird oft die Diesseitsbezogenheit des Shintō angeführt. Darüber hinaus kennt das klassische Shintō keine heiligen Schriften im Sinne eines religiösen Kanons, sondern wird weitgehend mündlich überliefert. Die beiden Schriften Kojiki und Nihonshoki, die von einigen shintoistisch geprägten Neureligionen Japans als heilig angesehen werden, sind eher historisch-mythologische Zeugnisse.[1]

神道(しんとう、しんどう[4])は、日本の宗教。惟神道(かんながらのみち)ともいう。教典や具体的な教えはなく、開祖もおらず、神話、八百万の神、自然や自然現象などにもとづくアニミズム的・祖霊崇拝的な民族宗教である[5]。

自然と神とは一体として認識され、神と人間を結ぶ具体的作法が祭祀であり、その祭祀を行う場所が神社であり、聖域とされた[6]。明治維新より第二次世界大戦終結まで政府によって事実上の国家宗教となった。この時期の神道を指して国家神道と呼ぶ。[7]。

Shinto,[a] also known as kami-no-michi,[b] is a religion originating in Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners Shintoists, although adherents rarely use that term themselves. There is no central authority in control of the movement and much diversity exists among practitioners.

Shinto is polytheistic and revolves around the kami ("gods" or "spirits"), supernatural entities believed to inhabit all things. The link between the kami and the natural world has led to Shinto being considered animistic and pantheistic. The kami are worshiped at kamidana household shrines, family shrines, and public shrines. The latter are staffed by priests who oversee offerings to the kami and the provision of religious paraphernalia such as amulets to the religion's adherents. Other common rituals include the kagura ritual dances, age specific celebrations, and seasonal festivals. These festivals and rituals are collectively called matsuri. A major conceptual focus in Shinto is ensuring purity by cleansing practices of various types including ritual washing or bathing. Shinto does not emphasize specific moral codes other than ritual purity, reverence for kami, and regular communion following seasonal practices. Shinto has no single creator or specific doctrinal text, but exists in a diverse range of localised and regionalised forms.

Belief in kami can be traced to the Yayoi period (300 BCE – 300 CE), although similar concepts existed during the late Jōmon period. At the end of the Kofun period (300 to 538 CE), Buddhism entered Japan and influenced kami veneration. Through Buddhist influence, kami came to be depicted anthropomorphically and were situated within Buddhist cosmology. Religious syncretisation made kami worship and Buddhism functionally inseparable, a process called shinbutsu-shūgō. The earliest written tradition regarding kami worship was recorded in the eighth-century Kojiki and Nihon Shoki. In ensuing centuries, shinbutsu-shūgō was adopted by Japan's Imperial household. During the Meiji era (1868 – 1912 CE), Japan's leadership expelled Buddhist influence from Shinto and formed State Shinto, which they utilized as a method for fomenting nationalism and imperial worship. Shrines came under growing government influence, and the Emperor of Japan was elevated to a particularly high position as a kami. With the formation of the Japanese Empire in the early 20th century, Shinto was exported to other areas of East Asia. Following Japan's defeat in World War II, Shinto was formally separated from the state.

Shinto is primarily found in Japan, where there are around 80,000 public shrines. Shinto is also practiced elsewhere, in smaller numbers. Only a minority of Japanese people identify as religious, although most of the population take part in Shinto matsuri and Buddhist activities, especially festivals, and seasonal events. This reflects a common view in Japanese culture that the beliefs and practices of different religions need not be exclusive. Aspects of Shinto have also been incorporated into various Japanese new religious movements.

Le shinto (神道, shintō, litt. « la voie des dieux » ou « la voie du divin ») ou shintoïsme (/ʃin.to.ism/) est un ensemble de croyances datant de l'histoire ancienne du Japon, parfois reconnues comme religion. Elle mélange des éléments polythéistes et animistes. Il s'agit de la plus ancienne religion connue du Japon ; elle est particulièrement liée à sa mythologie. Le terme « shintō », lecture sino-japonaise, ou kami no michi, est apparu pour différencier cette vieille religion du bouddhisme « importé » [Comment ?] de Chine au Japon au VIe siècle. Ses pratiquants seraient aujourd'hui plus de 90 millions au Japon.

Lo shintō, scintoismo o shintoismo[1] è una religione di natura politeista e animista nativa del Giappone.

Prevede l'adorazione dei "kami", cioè divinità, spiriti naturali o semplicemente presenze spirituali[1]. Alcuni kami sono locali e possono essere considerati come gli spiriti guardiani di un luogo particolare, ma altri possono rappresentare uno specifico oggetto o un evento naturale, come per esempio Amaterasu, la dea del Sole. Il Dio delle religioni monoteiste occidentali in giapponese viene tradotto come kami-sama (神様?). Talvolta anche le persone illustri, gli eroi e gli antenati divengono oggetto di venerazione post mortem e vengono deificati e annoverati tra i kami.

La parola Shinto ha origine nel VI secolo, quando divenne necessario distinguere la religione nativa del Giappone da quella buddista di recente importazione, prima di quell'epoca non pare esserci stato un nome specifico per riferirsi ad esso.[1][2] Shinto è formato dall'unione dei due kanji: 神 shin che significa "divinità", "spirito" (il carattere può essere anche letto come kami in giapponese ed è a sua volta formato dall'unione di altri due caratteri, 示 "altare" e 申 "parlare, riferire"; letteralmente ciò che parla, si manifesta dall'altare. 申 ne determina anche la lettura) e 道 tō in cinese Tao ("via", "sentiero" e per estensione; in senso filosofico rende il significato di pratica o disciplina come in Judo o Karatedo o ancora Aikidō). Quindi, Shinto significa letteralmente "via del divino".[1][3] In alternativa a Shinto, l'espressione puramente giapponese — con il medesimo significato — per indicare lo Shintoismo è Kami no michi.[4] Il termine "shintō" viene adoperato anche per indicare il corpo del nume, ovvero la reliquia presso cui il kami partecipa materialmente (per esempio una spada sacra).

Nella seconda metà del XIX secolo, nel contesto del Rinnovamento Meiji fu elaborato lo Shinto di Stato (国家神道 Kokka Shintō?), che mirava a dare un supporto ideologico e uno strumento di controllo sociale alla classe dirigente giapponese, e poneva al centro la figura dell'imperatore e della dea Amaterasu, progenitrice della stirpe imperiale. Lo Shinto di Stato fu smantellato alla fine della seconda guerra mondiale, con l'occupazione del Giappone. Alcune pratiche ed insegnamenti shintoisti che durante la guerra erano considerati di grande preminenza ora non sono più insegnati o praticati mentre altri rimangono grandemente diffusi come pratiche quotidiane senza però assumere particolari connotazioni religiose, come l'Omikuji (una forma di divinazione).

El sintoísmo1 (神道 Shintō?), a veces llamado shintoísmo,2 es el nombre de la religión nativa en Japón. Se basa en la veneración de los kami o espíritus de la naturaleza. Algunos kami son locales y son conocidos como espíritus o genios de un lugar en particular, pero otros representan objetos naturales mayores y procesos, por ejemplo, Amaterasu, la diosa del Sol.

Actualmente el sintoísmo constituye la segunda religión con mayor número de fieles de Japón, solo superada ligeramente por el budismo japonés. El número de practicantes varía desde los 108 millones (80 % de la población en 2003) que tienen prácticas y/o influencias sintoístas hasta los 4 millones (3,3 %) que lo practican regularmente y se identifican con la forma oficial de la religión.

Синтоизм, синто (яп. 神道 синто:, «путь богов») — традиционная религия в Японии. Основана на анимистических верованиях древних японцев, объектами поклонения являются многочисленные божества и духи умерших. Испытала в своём развитии значительное влияние буддизма.

History

History

I 500 - 0 BC

I 500 - 0 BC

History

History

H 1000 - 500 BC

H 1000 - 500 BC

History

History

J 0 - 500 AD

J 0 - 500 AD

History

History

K 500 - 1000 AD

K 500 - 1000 AD

Xizang Zizhiqu-XZ

Xizang Zizhiqu-XZ

贺茂御祖神社(日语:賀茂御祖神社)为一座位于京都市左京区的神社,被通称下鸭神社。为二十二社之一、式内社(名神大社)、山城国一宫、旧社格为官币大社(现神社本厅的别表神社)。主祭神为玉依媛命与贺茂建角身命。例祭日设在5月15日(贺茂祭、葵祭)。现任宫司为新木直人。

贺茂御祖神社是联合国科教文组织(UNESCO) 所登记的世界文化遗产之一,是遗产项目古都京都的文化财的其中一部分。

Der Shimogamo-Schrein (japanisch: 下鴨神社, Hepburn: Shimogamo-jinja) ist ein bedeutendes Shinto-Heiligtum im Bezirk Shimogamo des Kyotoer Stadtbezirks Sakyō. Sein offizieller Name ist Kamo-mioya-Schrein (賀茂御祖神社, Kamo-mioya-jinja) Er ist einer der ältesten Shinto-Schreine Japans und gehört zu den siebzehn historischen Denkmälern des alten Kyoto, die von der UNESCO zum Weltkulturerbe erklärt wurden.

Literature

Literature

Science and technology

Science and technology

Geography

Geography

Religion

Religion

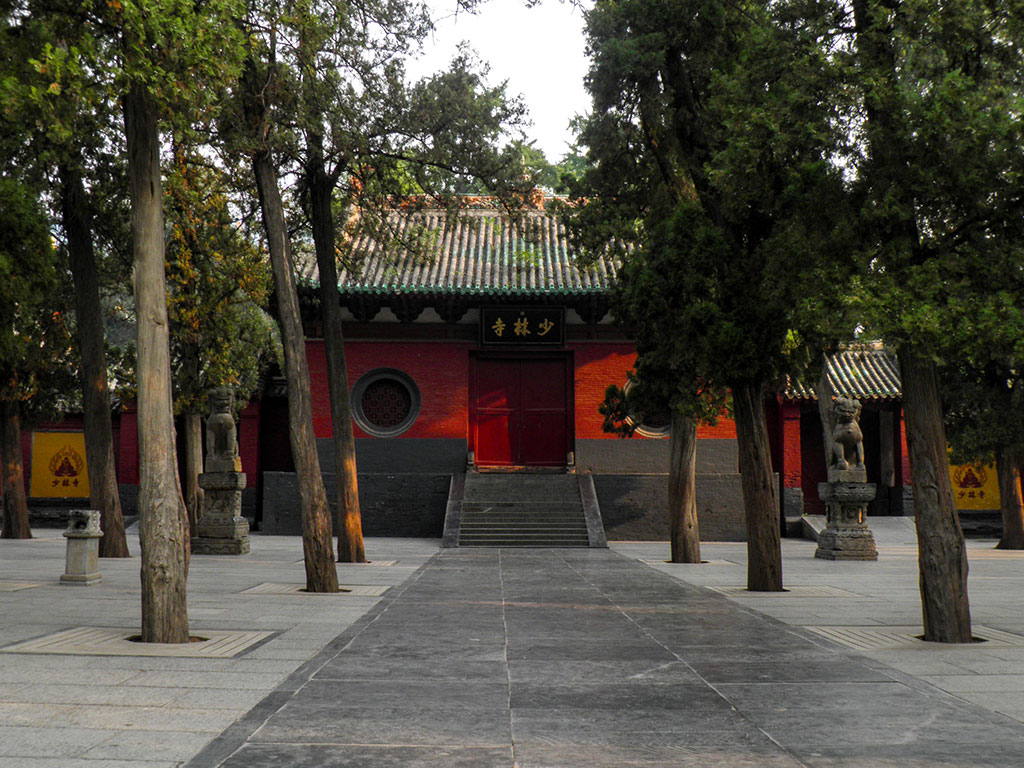

Architecture

Architecture

Art

Art

World Heritage

World Heritage

Military, defense and equipment

Military, defense and equipment

Life and Style

Life and Style

Sport

Sport