Deutsch-Chinesische Enzyklopädie, 德汉百科

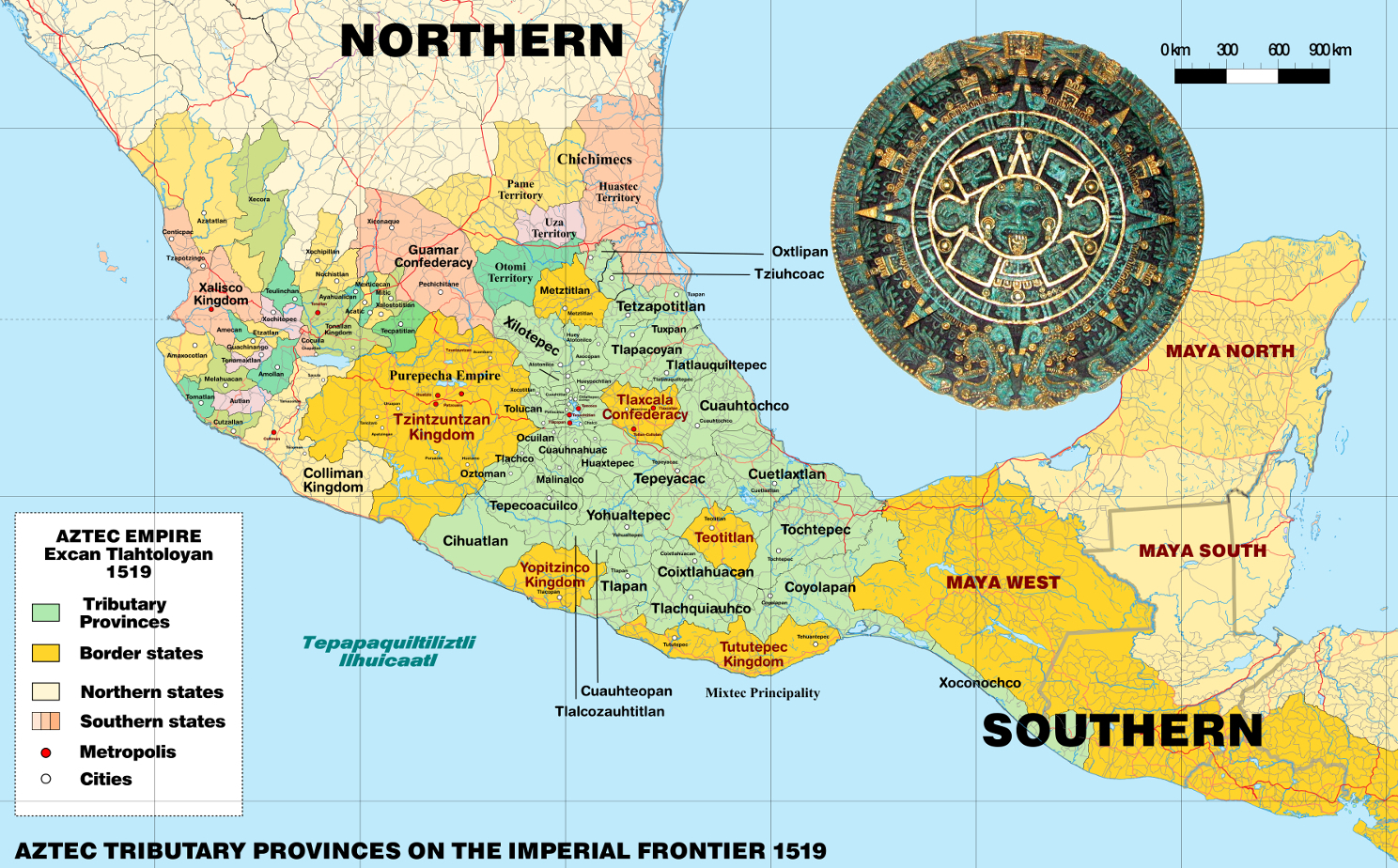

阿兹特克或阿兹台克是存在于14世纪至16世纪的墨西哥古文明,主要分布在墨西哥中部和南部,因阿兹特克人而得名。阿兹特克人包括墨西哥谷地的多个民族,以操纳瓦特尔语的族群为主。阿兹特克文明在政治上的基本单位是城邦,有些城邦组成政治联盟或政治邦联。其中,1427年建立的阿兹特克帝国最具影响力,帝国由墨西加城邦特诺奇蒂特兰、阿科尔瓦城邦特斯科科以及特帕内克城邦特拉科潘组成,政治影响力深远,领土范围极盛时东抵墨西哥湾,西至太平洋,南达恰帕斯和危地马拉。由于其强大的历史影响力,“阿兹特克”在狭义上常特指阿兹特克帝国;但广义来说,在殖民者入侵之前抑或是在西班牙殖民时代,中部美洲的所有纳瓦人政体和族群都可划作阿兹特克文明的一部分[1][2]。

阿兹特克人于约12世纪末由北方迁入墨西哥谷地,这里人口稠密,后来成为阿兹特克城邦崛起的中心。墨西加人是阿兹特克人的主要分支,他们在特斯科科湖中的岛礁建立起特诺奇蒂特兰城邦,并定居于此。1427年,特诺奇蒂特兰和特斯科科、特拉科潘结盟,联合击退了曾支配谷地的特帕内克城邦阿斯卡波察尔科。此三邦的联盟在后世被称为阿兹特克帝国,在随后的百余年内通过武力和贸易攻势展开扩张,成长为中部美洲势力范围最庞大的城邦联盟[3]。尽管被称为帝国,阿兹特克帝国事实上是一个以朝贡体系为基础的“朝贡帝国”,依托于扶植傀儡君主、政治联姻以及思想控制的方式间接控制其他城邦,强制其定期向宗主进贡,并不以军事驻防的方式实行直接统治[4]。帝国借此限制各邦同外部的贸易联系,使其属邦越发依赖帝国中央[5]。1519年,阿兹特克帝国的领土达到极盛,但一年后即迎来了欧洲人的历史性的访问。1520年,西班牙殖民者埃尔南·科尔特斯一行抵达中部美洲。科尔特斯利用中部美洲城邦间的矛盾,和阿兹特克的敌对城邦结盟,在1521年攻陷特诺奇蒂特兰,俘获并处决特拉托阿尼夸乌特莫克,并在特诺奇蒂特兰的废墟之上建起了现代墨西哥城。科尔特斯以此为中心实现对中部美洲全境的征服和殖民,将之纳入西班牙殖民帝国[6]。

近现代对阿兹特克文明的大规模研究始于19世纪,随着考古发掘和文献研究工作的进行,阿兹特克文明的文化、艺术和宗教逐渐为世人所了解。除了考古工作发现的古建筑和古物件外,既有的书面文献也起到重要作用,包括原住民手抄本、西班牙征服者的纪实文学,以及16世纪和17世纪由西班牙牧师或是有读写能力的阿兹特克人编撰的文化和历史文献等。十二卷手抄本佛罗伦萨手抄本是其中较为著名的文献,由方济各会修士贝尔纳迪诺·德萨阿贡结合一些阿兹特克人的描述写成,完整全面地记录了阿兹特克文明的文化、宗教、社会、经济和历史样貌。

德国地理学家冯·洪堡在19世纪早期率先用“阿兹特克”一词指代中部美洲纳瓦人以贸易、习俗、宗教、语言或政治联盟为纽带联系起来的文明集合体,“阿兹特克”一词就此被学界广泛接受和使用。不过,阿兹特克的具体界定也仍是一直以来学术讨论的主题之一[7]。根据中部美洲历史的断代法共识,900年至1521年的后古典时期内,中部美洲的绝大部分族群都拥有大体类似的文化烙印。因此,大部分普遍认为象征阿兹特克文明的文化元素并不是阿兹特克帝国的专属,因此对“阿兹特克文明”概念更贴切的理解是一种普遍存在的中部美洲文化体系[8],其农业以玉米栽培为主,社会形成皮尔利贵族和马塞瓦尔利平民的阶级分野,崇拜以特斯卡特利波卡、特拉洛克和克察尔科亚特尔为主的神系,历法系统由365天一周期的太阳历内嵌260天一周期的神圣历组成。与之相对应地,守护神祇维齐洛波奇特利、双子金字塔和阿兹特克陶制品则是阿兹特克人独有的文化符号[8]。现代墨西哥国家建立后,阿兹特克文化作为其国土上曾存在的重要文化而成为其现代国家认同的根基之一。特诺奇蒂特兰建城传说中雄鹰衔长蛇立于仙人掌之上的经典场面出现在墨西哥国旗和国徽上,为其重要的国家象征之一。

Die Azteken (von Nahuatl aztecatl, deutsch etwa „jemand, der aus Aztlán kommt“) waren eine mesoamerikanische Kultur, die zwischen dem 14. und dem frühen 16. Jahrhundert existierte. Im Allgemeinen bezeichnet man mit dem Begriff „Azteken“ die ethnisch heterogene, mehrheitlich Nahuatl sprechende Bevölkerung des Tals von Mexiko; im engeren Sinne sind damit aber nur die Bewohner von Tenochtitlán und der beiden anderen Mitglieder des sogenannten „Aztekischen Dreibundes“, der Städte Texcoco und Tlacopán, gemeint.

Ab dem späten 14. Jahrhundert weiteten die Azteken im Laufe der Jahre ihren politischen und militärischen Einfluss auf die umliegenden Städte und Völker aus, die nicht direkt dem Reich angegliedert, sondern zur Zahlung von Tributen gezwungen wurden. Auf dem Höhepunkt ihrer Macht kontrollierten sie weite Teile Zentralmexikos mit dem Tal von Mexiko als Zentrum. Zwischen 1519 und 1521 wurden die Azteken schließlich von den Spaniern unter Hernán Cortés unterworfen.

Die Azteken bezeichneten sich selbst meist als Mexica [meːˈʃiʔkaʔ], nach dem Namen des Ortes oder der Region Mexico – der Ursprung des heutigen Ländernamens Mexiko – bzw., nach ihren Siedlungsplätzen Tlatelolco und Tenochtitlán, auch Tlatelolca [tɬateˈloːlkaʔ] und Tenochca [teˈnoːtʃkaʔ]. In alten Quellen wird der Begriff „Azteken“ nur im Zusammenhang mit dem mythischen Herkunftsort Aztlán verwendet. Der erste, der ihn in moderner Zeit benutzte, war der Jesuit Francisco Javier Clavijero im 18. Jahrhundert; bekannt wurde er jedoch erst durch Alexander von Humboldt.

アステカ(Azteca、古典ナワトル語: Aztēcah)とは1428年頃から1521年までの約95年間北米のメキシコ中央部に栄えたメソアメリカ文明の国家。メシカ(古典ナワトル語: mēxihcah メーシッカッ)、アコルワ、テパネカの3集団の同盟によって支配され、時とともにメシカがその中心となった。言語は古典ナワトル語(ナワトル語)。

The Aztecs (/ˈæztɛks/) were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec peoples included different ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica from the 14th to the 16th centuries. Aztec culture was organized into city-states (altepetl), some of which joined to form alliances, political confederations, or empires. The Aztec empire was a confederation of three city-states established in 1427, Tenochtitlan, city-state of the Mexica or Tenochca; Texcoco; and Tlacopan, previously part of the Tepanec empire, whose dominant power was Azcapotzalco. Although the term Aztecs is often narrowly restricted to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan, it is also broadly used to refer to Nahua polities or peoples of central Mexico in the prehispanic era,[1] as well as the Spanish colonial era (1521–1821).[2] The definitions of Aztec and Aztecs have long been the topic of scholarly discussion, ever since German scientist Alexander von Humboldt established its common usage in the early nineteenth century.[3]

Most ethnic groups of central Mexico in the post-classic period shared basic cultural traits of Mesoamerica, and so many of the traits that characterize Aztec culture cannot be said to be exclusive to the Aztecs. For the same reason, the notion of "Aztec civilization" is best understood as a particular horizon of a general Mesoamerican civilization.[4] The culture of central Mexico includes maize cultivation, the social division between nobility (pipiltin) and commoners (macehualtin), a pantheon (featuring Tezcatlipoca, Tlaloc and Quetzalcoatl), and the calendric system of a xiuhpohualli of 365 days intercalated with a tonalpohualli of 260 days. Particular to the Mexica of Tenochtitlan was the patron God Huitzilopochtli, twin pyramids, and the ceramic ware known as Aztec I to IV.[5]

From the 13th century, the Valley of Mexico was the heart of dense population and the rise of city-states. The Mexica were late-comers to the Valley of Mexico, and founded the city-state of Tenochtitlan on unpromising islets in Lake Texcoco, later becoming the dominant power of the Aztec Triple Alliance or Aztec Empire. It was a tributary empire that expanded its political hegemony far beyond the Valley of Mexico, conquering other city states throughout Mesoamerica in the late post-classic period. It originated in 1427 as an alliance between the city-states Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan; these allied to defeat the Tepanec state of Azcapotzalco, which had previously dominated the Basin of Mexico. Soon Texcoco and Tlacopan were relegated to junior partnership in the alliance, with Tenochtitlan the dominant power. The empire extended its reach by a combination of trade and military conquest. It was never a true territorial empire controlling a territory by large military garrisons in conquered provinces, but rather dominated its client city-states primarily by installing friendly rulers in conquered territories, by constructing marriage alliances between the ruling dynasties, and by extending an imperial ideology to its client city-states.[6] Client city-states paid tribute to the Aztec emperor, the Huey Tlatoani, in an economic strategy limiting communication and trade between outlying polities, making them dependent on the imperial center for the acquisition of luxury goods.[7] The political clout of the empire reached far south into Mesoamerica conquering polities as far south as Chiapas and Guatemala and spanning Mesoamerica from the Pacific to the Atlantic oceans.

The empire reached its maximal extent in 1519, just prior to the arrival of a small group of Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés. Cortés allied with city-states opposed to the Mexica, particularly the Nahuatl-speaking Tlaxcalteca as well as other central Mexican polities, including Texcoco, its former ally in the Triple Alliance. After the fall of Tenochtitlan on August 13, 1521 and the capture of the emperor Cuauhtemoc, the Spanish founded Mexico City on the ruins of Tenochtitlan. From there they proceeded with the process of conquest and incorporation of Mesoamerican peoples into the Spanish Empire. With the destruction of the superstructure of the Aztec Empire in 1521, the Spanish utilized the city-states on which the Aztec Empire had been built, to rule the indigenous populations via their local nobles. Those nobles pledged loyalty to the Spanish crown and converted, at least nominally, to Christianity, and in return were recognized as nobles by the Spanish crown. Nobles acted as intermediaries to convey tribute and mobilize labor for their new overlords, facilitating the establishment of Spanish colonial rule.[8]

Aztec culture and history is primarily known through archaeological evidence found in excavations such as that of the renowned Templo Mayor in Mexico City; from indigenous writings; from eyewitness accounts by Spanish conquistadors such as Cortés and Bernal Díaz del Castillo; and especially from 16th- and 17th-century descriptions of Aztec culture and history written by Spanish clergymen and literate Aztecs in the Spanish or Nahuatl language, such as the famous illustrated, bilingual (Spanish and Nahuatl), twelve-volume Florentine Codex created by the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún, in collaboration with indigenous Aztec informants. Important for knowledge of post-conquest Nahuas was the training of indigenous scribes to write alphabetic texts in Nahuatl, mainly for local purposes under Spanish colonial rule. At its height, Aztec culture had rich and complex mythological and religious traditions, as well as achieving remarkable architectural and artistic accomplishments.

Les Aztèques, ou Mexicas (du nom de leur capitale, Mexico-Tenochtitlan), étaient un peuple amérindien du groupe nahua, c'est-à-dire de langue nahuatl.

Ils s'étaient définitivement sédentarisés dans le plateau central du Mexique, dans la vallée de Mexico, sur une île du lac Texcoco, vers le début du XIVe siècle. Au début du XVIe siècle, ils avaient atteint un niveau de civilisation parmi les plus avancés d'Amérique et dominaient, avec les autres membres de leur Triple alliance, le plus vaste empire de la Mésoamérique postclassique. Leur seul vrai rival était le royaume tarasque.

L'arrivée, en 1519, des conquistadors menés par Hernán Cortés scella la fin de leur règne. Le 13 août 1521, les Espagnols, aidés par un grand nombre d’alliés autochtones, finirent par remporter le siège de Tenochtitlan et par capturer le dernier dirigeant aztèque, Cuauhtémoc. La civilisation aztèque s'est alors rapidement acculturée à l'époque coloniale ; il en résulte un profond syncrétisme dans le Mexique actuel entre les héritages aztèques (et, plus largement, mésoaméricains) et espagnols.

Les études de cette civilisation précolombienne se fondent sur les codex mésoaméricains, livres écrits par les autochtones sur papier d'amate, les témoignages des conquistadors, comme Hernán Cortés et Bernal Díaz del Castillo, les travaux des chroniqueurs du XVIe et XVIIe siècles, comme le codex de Florence compilé par le moine franciscain Bernardino de Sahagún avec l'aide de collaborateurs aztèques, ainsi que, depuis la fin du XVIIIe siècle, les recherches archéologiques, grâce aux fouilles comme celles du Templo Mayor de la ville de Mexico.

I Mexica (pron. mescìca; Nahuatl: Mēxihcah [meːˈʃiʔkaʔ], singolare Mēxihcatl) o Mexicas — meglio noti come Aztechi nella storiografia occidentale - furono una delle grandi civiltà precolombiane, la più florida e viva al momento del contatto con gli Spagnoli. Provenienti dalla California settentrionale, si svilupparono nella regione mesoamericana dell'attuale Messico dal secolo XIV al XVI.

Il nome con cui essi stessi si indicavano è "Mexica" o "Tenochca", e non Aztechi, non a caso Mexica è tuttora il termine usato per definire i loro discendenti; il termine Azteco è invece stato coniato solo molti secoli dopo dal geografo tedesco Alexander von Humboldt per distinguere queste popolazioni precolombiane dall'insieme dei Messicani moderni. Spesso con il termine "azteco" ci si riferisce esclusivamente al popolo residente a Tenochtitlán (dove oggi si trova Città del Messico), situata su un'isola del lago Texcoco, che faceva riferimento a se stessa come Mēxihcah Tenochcah [meːˈʃiʔkaʔ teˈnot͡ʃkaʔ] o Cōlhuah Mēxihcah [ˈkoːlwaʔ meːˈʃiʔkaʔ].

Talvolta il termine comprende anche gli abitanti delle due principali città-stato alleate di Tenochtitlan, gli Acolhua di Texcoco e i Tepanechi di Tlacopan, che insieme con i Mexica formavano la Triplice alleanza azteca spesso conosciuta come "impero azteco". In altri contesti, "azteco" può riferirsi a tutti i vari stati della città e dei loro popoli che hanno condiviso gran parte della loro storia etnica e tratti culturali con i Mexica, con gli Acolhua e con i Tepanechi e che spesso utilizzavano la lingua nahuatl come lingua franca. In questo senso si può parlare di una civiltà azteca comprensiva di tutti i modelli culturali comuni per la maggior parte dei popoli che abitarono il Messico centrale nel periodo tardo post-Classico.

A partire dal XIII secolo, la Valle del Messico è stata il cuore della civiltà azteca; qui la capitale della Triplice alleanza azteca, la città di Tenochtitlan, fu costruita su isole nel lago Texcoco. La Triplice Alleanza formò un impero tributario che espanse la propria egemonia politica ben oltre la Valle del Messico, conquistando altre città di tutto il Mesoamerica. Al suo apice, la cultura azteca vantava ricche e complesse tradizioni mitologiche e religiose, oltre ad aver raggiunto la capacità di realizzare notevoli manufatti architettonici e artistici. Nel 1521 Hernán Cortés, conquistò Tenochtitlan e sconfisse la Triplice alleanza azteca che al momento si trovava sotto la guida di Montezuma II (vedi Conquista dell'impero azteco). Successivamente, gli spagnoli fondarono il nuovo insediamento di Città del Messico sul sito della capitale azteca in rovina; da qui poi procedettero con il processo di colonizzazione dell'America Centrale.

La cultura e la storia azteca sono conosciute principalmente attraverso le testimonianze archeologiche rinvenute negli scavi, come quello del famoso Templo Mayor a Città del Messico; da codici scritti su corteccia; da testimonianze oculari dei conquistadores spagnoli come Hernán Cortés e Bernal Díaz del Castillo; e soprattutto dalle descrizioni del XVI e XVII secolo della cultura e della storia scritti da ecclesiastici spagnoli e da letterati Aztechi, come il famoso Codice Fiorentino compilato dal frate francescano Bernardino de Sahagún con l'aiuto di informatori originari aztechi.

Los mexicas (del náhuatl mēxihcah ![]() [meː'ʃiʔkaʔ] (?·i), «mexicas»1) —llamados en la historiografía tradicional aztecas2— fueron un pueblo mesoamericano de filiación nahua que fundó México-Tenochtitlan y hacia el siglo XV en el periodo posclásico tardío se convirtió en el centro de uno de los Estados más extensos que se conoció en Mesoamérica, asentado en un islote al poniente del lago de Texcoco, sobre los márgenes centro y el sur de los lagos, como en Huexotla, Coatlinchan, Culhuacan, Iztapalapa, Chalco, Xico, Xochimilco, Tacuba, Azcapotzalco, Tenayuca y Xaltocan, hacia finales del Posclásico Temprano (900-1200),3 hoy prácticamente desecado. Sobre el islote se asienta la actual Ciudad de México, y que corresponde a la misma ubicación geográfica. Aliados con otros pueblos de la cuenca lacustre del valle de México —Tlacopan y Texcoco—, los mexicas sometieron a varias poblaciones indígenas que se asentaron en el centro y sur del territorio actual de México agrupados territorialmente en altépetl.

[meː'ʃiʔkaʔ] (?·i), «mexicas»1) —llamados en la historiografía tradicional aztecas2— fueron un pueblo mesoamericano de filiación nahua que fundó México-Tenochtitlan y hacia el siglo XV en el periodo posclásico tardío se convirtió en el centro de uno de los Estados más extensos que se conoció en Mesoamérica, asentado en un islote al poniente del lago de Texcoco, sobre los márgenes centro y el sur de los lagos, como en Huexotla, Coatlinchan, Culhuacan, Iztapalapa, Chalco, Xico, Xochimilco, Tacuba, Azcapotzalco, Tenayuca y Xaltocan, hacia finales del Posclásico Temprano (900-1200),3 hoy prácticamente desecado. Sobre el islote se asienta la actual Ciudad de México, y que corresponde a la misma ubicación geográfica. Aliados con otros pueblos de la cuenca lacustre del valle de México —Tlacopan y Texcoco—, los mexicas sometieron a varias poblaciones indígenas que se asentaron en el centro y sur del territorio actual de México agrupados territorialmente en altépetl.

Los mexicas se caracterizaban por la explotación de cultivos altamente simbióticos (dependencia a la manipulación humana,4556 como maíz, chile, calabaza, frijol, etc.), el uso extensivo de plumas para la confección de vestimentas, el uso de calendarios astronómicos (uno ritual de 260 días y un civil de 365), una sofisticada metalurgia prehispánica ornamental y militar basada principalmente en el bronce, oro y plata;7 una escritura en forma de pictogramas el cual era usado para la documentación de hechos y el cálculo de obras arquitectónicas el cual estaba basado en un sistema métrico propio,8 que para mediciones de terrenos es comparable con otros sistemas de medida de la Edad Moderna,9 el uso extensivo de productos derivados de las cactáceas y agaves, y el uso de cerámico ígneo (obsidiana) para fines quirúrgicos y bélicos.

Ацте́ки, или асте́ки[1] (самоназв. mēxihcah [meː'ʃiʔkaʔ]), — индейский народ в центральной Мексике. Численность современных науа, как ещё называют ацтеков, — свыше 1,5 млн человек. Цивилизация ацтеков (XIV—XVI века) обладала богатой мифологией и культурным наследием. Столицей империи ацтеков был город Теночтитлан, расположенный на озере Тескоко, там, где сейчас располагается город Мехико.

巴鲁赫·斯宾诺莎(拉迪诺语:Baruch de Spinoza,拉丁语:Benedictus de Spinoza,1632年11月24日—1677年2月21日)是荷兰的哲学家。斯宾诺莎是17世纪理性主义先驱,启蒙时代[5][6]以及现代圣经批判学[7]的开创者,他的作品引导了现代对自我及宇宙的认识[8],因此被认为是“近世最重要的哲学家之一”。[9][10][11] 斯宾诺莎继承了勒内·笛卡尔的思想,是荷兰黄金时代的哲学领军者。斯宾诺莎的名字“巴鲁赫”意为“受祝福的”,在不同语言中写法各不相同。在希伯来语中,他的名字写为 ברוך שפינוזה,在现代犹太团体中,他的名字被写为“Bento”(“受祝福的”葡萄牙语)。[12] 在斯宾诺莎的拉丁语作品中,他使用本尼迪克特·德·斯宾诺莎这个名字。

斯宾诺莎生于阿姆斯特丹的西班牙-葡萄牙-犹太社区。因对希伯来圣经的真实性和神性本质提出了极具争议的观点,葡萄牙犹太会堂向他发出谴责令,23岁的斯宾诺莎(包括他的家人)被逐出教会。斯宾诺莎去世后不久,他的作品随即被天主教会列为禁书。同时代人常称斯宾诺莎为“无神论者”,尽管斯宾诺莎从未在自己作品中怀疑上帝的存在。[13][14][15] 斯宾诺莎生活简朴,以打磨镜片为生,他曾参与制作惠更斯兄弟设计的望远镜。斯宾诺莎回绝他人提供的资助和奖赏,并拒绝了荣誉性的教职工作。或许是因为常年打磨镜片吸入过量粉尘,斯宾诺莎于1677年死于肺病,年仅44岁。他被葬于海牙新教堂墓地。[16]

斯宾诺莎的哲学研究几乎涵盖所有领域,包括形而上学、认识论、政治哲学、伦理学、心灵哲学、科学哲学。因此,人们普遍认为斯宾诺莎是17世纪最重要的哲学家之一。他的哲学思想主要体现在两部著作《神学政治论》和《伦理学》中。其余作品要么是早期思想,要么是未完成作品,其中理论在前述两部著作中都有涉及(例如《政治论》),或者不作为斯宾诺莎的哲学重点(例如《笛卡尔哲学原理》和《希伯来语语法书》)。与此同时,斯宾诺莎也留下了许多通讯信件,其中内容可为其哲学思想作出明晰解释,或展示出他哲学观点的演化历程。[17][9]

斯宾诺莎的著作《伦理学》于死后发表,这部作品让他成为了西方哲学中最重要的思想家之一。斯宾诺莎在此书中对笛卡尔的身心二元论提出质疑,据罗杰·斯克鲁顿所言,“斯宾诺莎在这最后一本拉丁文杰作中指出了中世纪哲学细致概念背后的巨大缺陷,它们最终将反对自身,并完全覆灭”。[18] 黑格尔曾表示“斯宾诺莎哲学是近代哲学的重点,要么是斯宾诺莎主义,要么就不是哲学。”[19] 鉴于斯宾诺莎的巨大成就及高尚品格,吉尔·德勒兹称他为“哲学王子”。

Baruch de Spinoza (hebräisch ברוך שפינוזה, portugiesisch Bento de Espinosa, latinisiert Benedictus de Spinoza; geboren am 24. November 1632 in Amsterdam; gestorben am 21. Februar 1677 in Den Haag) war ein niederländischer Philosoph. Er war Sohn sephardischer Immigranten aus Portugal und hatte Portugiesisch als Erstsprache.[1] Er wird dem Rationalismus zugeordnet und gilt als einer der Begründer der modernen Bibel- und Religionskritik.

Architecture

Architecture

Renaissance architecture

Renaissance architecture

Architecture

Architecture

Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture

History

History

M 1500 - 2000 AD

M 1500 - 2000 AD

Marche

Marche

Religion

Religion

Architecture

Architecture

Neo-Byzantine architecture

Neo-Byzantine architecture

Renaissance architecture

Renaissance architecture

Russian Renaissance

Russian Renaissance

History

History

M 1500 - 2000 AD

M 1500 - 2000 AD

Religion

Religion

Russia

Russia

World Heritage

World Heritage

聖ワシリイ大聖堂(露:Собор Василия Блаженного)はロシアの首都、モスクワの赤の広場に立つロシア正教会の大聖堂。正式名称は「堀の生神女庇護大聖堂」(Собор Покрова, что на Рву、詳細は#名称・記憶を参照)。

「聖ワシリー大聖堂」「聖ヴァシーリー大聖堂」「聖ワシーリー寺院」とも日本では表記される。

1551年から1560年にかけて、イヴァン4世(雷帝)が、カザン・ハーンを捕虜とし勝利したことを記念して建立した。ロシアの聖堂でもっとも美しい建物のひとつと言われる。1990年にユネスコの世界遺産に登録された。

ゲームソフト等で有名なテトリスでは、ロシア文化をイメージとした背景や音楽等がよく用いられており、聖ワシリイ大聖堂もしばしば背景画像やパッケージとして使われている。

「クレムリンの聖ワシリイ大聖堂」といった説明がされることもあるが、大聖堂はクレムリンの城壁の内側には位置していないため誤りである。聖ワシリイ大聖堂が位置する赤の広場はクレムリンの城壁の外側にある。

The Cathedral of Vasily the Blessed (Russian: собо́р Васи́лия Блаже́нного, Sobor Vasiliya Blazhennogo), commonly known as Saint Basil's Cathedral, is an Orthodox church in Red Square of Moscow, and is one of the most popular cultural symbols of Russia. The building, now a museum, is officially known as the Cathedral of the Intercession of the Most Holy Theotokos on the Moat, or Pokrovsky Cathedral.[5] It was built from 1555 to 1561 on orders from Ivan the Terrible and commemorates the capture of Kazan and Astrakhan. It was the city's tallest building until the completion of the Ivan the Great Bell Tower in 1600.[6]

The original building, known as Trinity Church and later Trinity Cathedral, contained eight chapels arranged around a ninth, central chapel dedicated to the Intercession; a tenth chapel was erected in 1588 over the grave of the venerated local saint Vasily (Basil). In the 16th and 17th centuries, the church, perceived (as with all churches in Byzantine Christianity) as the earthly symbol of the Heavenly City,[7] was popularly known as the "Jerusalem" and served as an allegory of the Jerusalem Temple in the annual Palm Sunday parade attended by the Patriarch of Moscow and the Tsar.[8]

The cathedral has nine domes (each one corresponding to a different church) and is shaped like the flame of a bonfire rising into the sky,[9] a design that has no parallel in Russian architecture. Dmitry Shvidkovsky, in his book Russian Architecture and the West, states that "it is like no other Russian building. Nothing similar can be found in the entire millennium of Byzantine tradition from the fifth to the fifteenth century ... a strangeness that astonishes by its unexpectedness, complexity and dazzling interleaving of the manifold details of its design."[10] The cathedral foreshadowed the climax of Russian national architecture in the 17th century.[11]

La cattedrale dell'Intercessione della Madre di Gesù sul Fossato, popolarmente nota come cattedrale di San Basilio, è una cattedrale della Chiesa ortodossa russa eretta sulla Piazza Rossa di Mosca tra il 1555 e il 1561 (XVI). Costruita per volontà di Ivan IV di Russia per commemorare la presa di Kazan' e Astrachan', essa rappresenta il centro geometrico della città e il fulcro della sua crescita già dal XIV secolo.[1] È stato il più alto edificio della città di Mosca fino al completamento della Grande Torre Campanaria di Ivan il Grande, avvenuto nel 1600.[2]

L'edificio originale, noto come la chiesa della Trinità e successivamente come cattedrale della Trinità, constava di otto chiese laterali distribuite intorno alla nona, centrale, chiesa dell'Intercessione; la decima chiesa venne eretta nel 1588 sopra la tomba del venerato stolto Basilio il Benedetto. Durante il XVI e il XVII secolo la cattedrale, percepita come il simbolo in terra della Città celeste,[3] era popolarmente conosciuta come Gerusalemme e rappresentava un'allegoria del Tempio di Gerusalemme durante l'annuale parata della Domenica delle Palme capeggiata dal Patriarca di Mosca e dallo zar.[4]

Il disegno dell'edificio, la cui forma ricorda «le fiamme di un falò che sale verso il cielo»,[5] non ha analoghi nell'architettura russa: «Non è come nessun altro edificio russo. Niente di simile può essere trovato nell'intero millennio di tradizione bizantina intercorso tra il V e il XV secolo… una stranezza che lascia attoniti per l'imprevedibilità, la complessità e l'abbagliante fioritura dei dettagli riprodotti nel suo disegno.»[6] La cattedrale anticipò la climax dell'architettura nazionale russa del XVII secolo,[7] ma non è mai stata riprodotta direttamente.

La cattedrale ha operato come divisione del Museo Storico di Stato già dal 1928. Venne completamente secolarizzata nel 1929 e, al 2009, risulta ancora proprietà della Federazione russa. La cattedrale è inclusa dal 1990 come Patrimonio dell'umanità nella lista UNESCO, insieme con il Cremlino di Mosca.[8]

La Catedral de la Intercesión de la Santísima Virgen en el Montículo (en ruso Собор Покрова Пресвятой Богородицы, что на Рву, Sobor Pokrová Presvyatoy Bogoróditsy, chto na Rvu), más conocida como Catedral de San Basilio, es un templo ortodoxo localizado en la Plaza Roja de la ciudad de Moscú, Rusia. Es mundialmente famosa por sus cúpulas en forma de bulbo. A pesar de lo que se suele pensar popularmente, la Catedral de San Basilio no es ni la sede del Patriarca Ortodoxo de Moscú, ni la catedral principal de la capital rusa, pues en ambos casos es la Catedral de Cristo Salvador. Como parte de la Plaza Roja, la catedral de San Basilio fue incluida desde 1990, junto con el conjunto del Kremlin, en la lista de Patrimonio de la Humanidad de Unesco.2

La construcción de la catedral fue ordenada por el zar Iván el Terrible para conmemorar la conquista del Kanato de Kazán, y se realizó entre 1555 y 1561. En 1588, el zar Teodoro I de Rusia mandó que se agregara una nueva capilla en el lado este de la construcción, sobre la tumba de San Basilio el Bendito, santo por el cual se empezó a llamar popularmente la catedral.

San Basilio se encuentra en el extremo sureste de la Plaza Roja, justo frente a la Torre Spásskaya (la Torre del Salvador) del Kremlin y la iglesia de San Juan Bautista en Dyákovo.

En un jardín frente a la iglesia se levanta el Monumento a Minin y Pozharsky, una estatua de bronce en honor a Dmitri Pozharski y Kuzmá Minin, quienes reunieron voluntarios para el ejército que luchó contra los invasores polacos durante el conocido como Período Tumultuoso.

El concepto inicial era construir un grupo de capillas, dedicadas a cada uno de los santos en cuyo día el zar ganó una batalla, pero la construcción de una torre central unifica estos espacios en una sola catedral.

La leyenda dice que el zar Iván dejó ciego al arquitecto Póstnik Yákovlev para evitar que proyectara una construcción que pudiera superar a esta, aunque parece claro que no se trata más que de una fabulación, ya que Yákovlev participó, pasados unos años, en la construcción del Kremlin de Kazán.

La catedral de San Basilio no debe confundirse con el Kremlin de Moscú, que está situado a su lado en la Plaza Roja, y por tanto no forma parte de él. Aun así, muchos medios confunden ambas construcciones.

Собо́р Покрова́ Пресвято́й Богоро́дицы, что на Рву (Покро́вский собо́р, собо́р Покрова́ на Рву, разговорное — собо́р (храм) Васи́лия Блаже́нного) — православный храм на Красной площади в Москве, памятник русской архитектуры. Строительство собора велось с 1555 по 1561 год[1][2].

Собор объединяет одиннадцать церквей (приделов), часть из которых освящена в честь святых, дни памяти которых пришлись на решающие бои за Казань[3]. Центральная церковь сооружена в честь Покрова Богородицы, вокруг которой группируются отдельные церкви в честь: Святой Троицы, Входа Господня в Иерусалим, Николы Великорецкого, Трёх Патриархов: Александра, Иоанна и Павла Нового, Григория Армянского, Киприана и Иустины, Александра Свирского и Варлаама Хутынского, размещённые на одном основании-подклете, а также придел в честь Василия Блаженного[4][5], по имени которого храм получил второе, более известное название, и церковь Иоанна Блаженного, вновь открытая после длительного запустения в ноябре 2018 года[6].

В названии собора упомянут ров, проходивший вдоль Кремлёвской стены и служивший оборонительным укреплением (Алевизов ров), его глубина была около 13 метров, а ширина — около 36 метров[7][8].

Собор входит в российский список объектов Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО и является филиалом Государственного исторического музея[9].

Civilization

Civilization

Aerospace

Aerospace

Astronomy

Astronomy

Science and technology

Science and technology

Financial

Financial

Historical coins, banknotes

Historical coins, banknotes

Aragón

Aragón

Emilia-Romagna

Emilia-Romagna

Review

Review