漢德百科全書 | 汉德百科全书

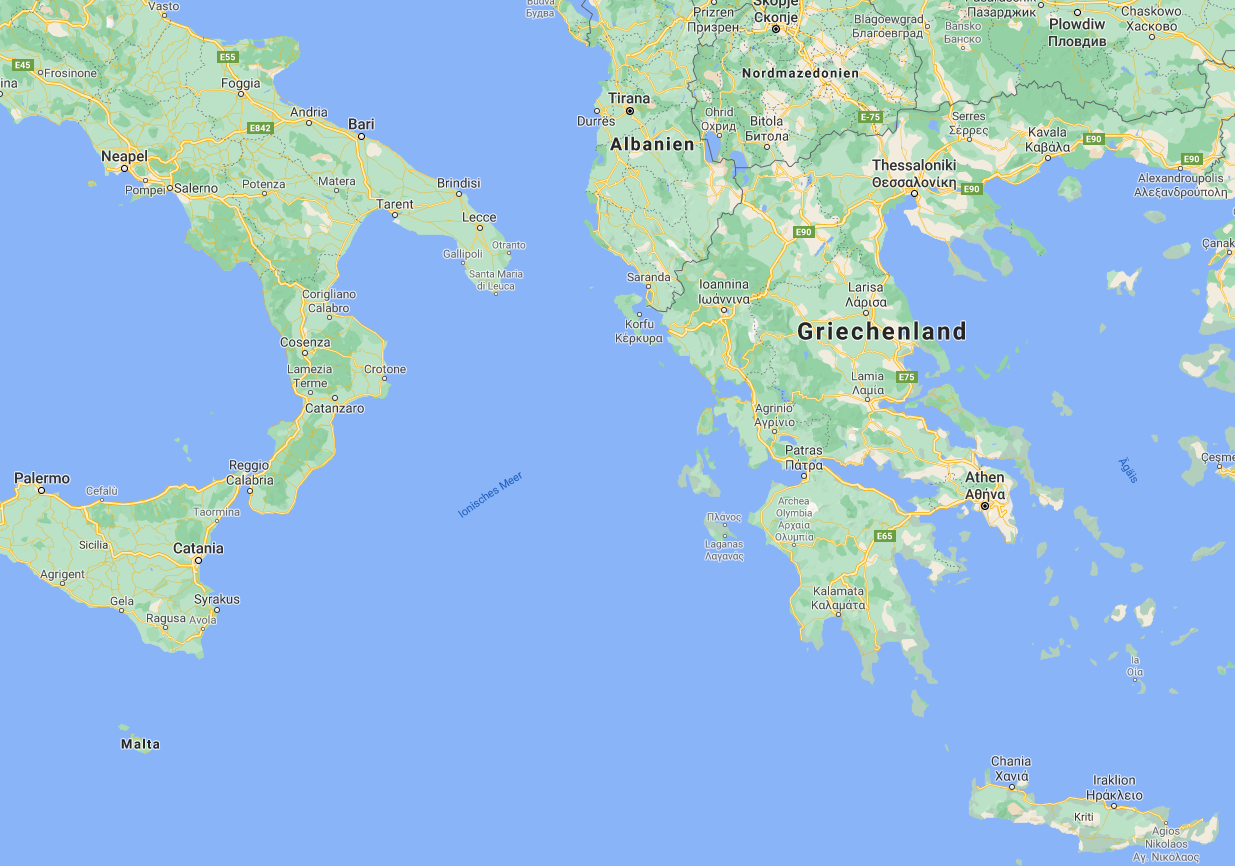

*Mittelmeer

*Mittelmeer

Das Osmanische Reich (osmanisch دولت علیه İA Devlet-i ʿAlīye, deutsch ‚der erhabene Staat‘ und ab 1876 amtlich دولت عثمانيه / Devlet-i ʿOs̲mānīye / ‚der osmanische Staat‘, türkisch Osmanlı İmparatorluğu) war das Reich der Dynastie der Osmanen von ca. 1299 bis 1922. In Westeuropa wurde das Land ab dem 12. Jahrhundert auch als „Turchia“ („Türkei“ oder Türkisches Reich) bezeichnet.[6] Die im deutschsprachigen Raum veraltete,[7] in der englisch-[8] und französischsprachigen Literatur[9] noch anzutreffende Bezeichnung Ottomanisches Reich leitet sich von Varianten der arabischen Namensform Uthman des Dynastiebegründers Osman I. her.

Es entstand Anfang des 14. Jahrhunderts als regionaler Herrschaftsbereich (Beylik) im nordwestlichen Kleinasien im Grenzgebiet des byzantinischen Reichs unter einem Anführer mutmaßlich nomadischer Herkunft. Dieser löste sich aus der Abhängigkeit vom Sultanat der Rum-Seldschuken, welches nach 1243 unter die Vorherrschaft des mongolischen Ilchanats geraten war und seine Macht eingebüßt hatte. Hauptstadt war ab 1326 Bursa, ab 1368 Adrianopel, schließlich seit 1453 Konstantinopel (osmanisch Kostantiniyye; seit 1876 offiziell Istanbul genannt).

Zur Zeit seiner größten Ausdehnung im 17. Jahrhundert erstreckte es sich von seinen Kernlanden Kleinasien und Rumelien nordwärts bis in das Gebiet um das Schwarze und das Asowsche Meer, westwärts bis weit nach Südosteuropa hinein. Jahrhundertelang beanspruchte das Osmanische Reich politisch, militärisch und wirtschaftlich eine europäische Großmachtrolle neben dem Heiligen Römischen Reich, Frankreich und England. Im Mittelmeer kämpfte das Reich mit den italienischen Republiken Venedig und Genua, dem Kirchenstaat und dem Malteserorden um die wirtschaftliche und politische Vormachtstellung. Ab dem 18. bis ins späte 19. Jahrhundert hinein rang es mit dem russischen Zarenreich um die Herrschaft über die Schwarzmeerregion. Im Indischen Ozean forderte das Reich Portugal im Kampf um den Vorrang im Fernhandel mit Indien und Indonesien heraus. Durch die ununterbrochen intensiven politischen, wirtschaftlichen und kulturellen Beziehungen ist die Geschichte des Osmanischen Reichs mit derjenigen Westeuropas eng verbunden.

Im Nahen Osten beherrschten die Osmanen mit Syrien, dem Gebiet des heutigen Irak und dem Hedschas (mit den heiligen Städten Mekka und Medina) die historischen Kernlande des Islam, in Nordafrika unterstand das Gebiet von Nubien über Oberägypten westwärts bis zum mittleren Atlasgebirge der osmanischen Herrschaft. In der islamischen Welt stellte das Osmanische Reich nach dem Umayyaden- und Abbasidenreich die dritte und letzte sunnitische Großmacht dar. Nachdem in Persien die Dynastie der Safawiden die Schia als Staatsreligion durchgesetzt hatte, setzten beide Reiche den alten innerislamischen Konflikt zwischen beiden islamischen Bekenntnissen in drei großen Kriegen fort.

Im Laufe des 18. und vor allem im 19. Jahrhundert erlitt das Reich in Auseinandersetzungen mit den europäischen Mächten sowie durch nationale Unabhängigkeitsbestrebungen in seinen rumelischen Kernlanden erhebliche Gebietsverluste. Sein Territorium verkleinerte sich auf das europäische Thrakien sowie auf Kleinasien. Die Niederlage der Habsburger- und Hohenzollernmonarchie, mit denen sich das Osmanische Reich im Ersten Weltkrieg verbündet hatte, führte – zeitgleich mit dem Ende des Russischen Kaiserreichs – innerhalb weniger Jahre zum fast gleichzeitigen Ende vier großer Monarchien, die die Geschichte Europas über Jahrhunderte hinweg geprägt hatten. Im Türkischen Befreiungskrieg setzte sich eine Nationalregierung unter Mustafa Kemal Pascha durch; 1923 wurde als Nachfolgestaat die Republik Türkei gegründet.

奥斯曼帝国(奥斯曼土耳其语:دولت عالیه عثمانیه,土耳其语:Osmanlı İmparatorluğu),中文又常称为奥斯曼土耳其帝国,为奥斯曼人建立的帝国,创立者为奥斯曼一世。奥斯曼人初居中亚,后迁至小亚细亚,日渐兴盛。极盛时势力达亚欧非三大洲,领有南欧、巴尔干半岛、西亚及北非之大部分领土,西达直布罗陀海峡,东抵里海及波斯湾,北及今之奥地利和斯洛文尼亚,南及今之苏丹与也门。自消灭东罗马帝国后,定都于君士坦丁堡,且以东罗马帝国的继承人自居。故奥斯曼帝国的君主苏丹以自封的形式,视自己为天下之主,继承了东罗马帝国的基督教文化及伊斯兰文化,因而东西文明在其得以统合[5]。

奥斯曼帝国位处东西文明交汇处,并掌握东西文明的陆上交通线达六个世纪之久,直至大英帝国在18世纪通过直布罗舵打通地中海航线为止。在其存在期间,不止一次实行伊斯兰化与现代化改革,使得东西文明的界限日趋模糊[6]。奥斯曼帝国对西方文明影响举足轻重,其建筑师希南名留至今。16世纪,苏莱曼大帝在位之时,日趋鼎盛,其领土在17世纪更达最高峰,控制今日中东欧不少国家。在巴巴罗萨的带领下,其海军更掌控地中海。

奥斯曼帝国是15世纪至19世纪唯一能挑战崛起的欧洲基督教国家的伊斯兰教势力,但奥斯曼帝国终不能抵挡近代化欧洲列强的冲击,于19世纪初趋于没落,沦为英国、法国等列强的棋子,但其卓越的战略地理位置使英国、法国得以利用奥斯曼帝国阻止俄罗斯帝国对外向欧洲扩张,并在克里米亚战争中成功阻止,最终于第一次世界大战里败于协约国之手,奥斯曼帝国因而分裂。之后凯末尔领导土耳其国民运动,放弃了大奥斯曼土耳其帝国的疆域,建立了主权独立但面积较小、仅控制色雷斯及小亚细亚的土耳其共和国,奥斯曼帝国至此灭亡。

オスマン帝国(オスマンていこく、オスマントルコ語: دولتِ عليۀ عثمانيه, ラテン文字転写: Devlet-i ʿAliyye-i ʿOs̠māniyye)は、テュルク系(後のトルコ人)のオスマン家出身の君主(皇帝)を戴く多民族帝国。英語圏ではオットマン帝国 (Ottoman Empire) と表記される。15世紀には東ローマ帝国を滅ぼしてその首都であったコンスタンティノポリスを征服、この都市を自らの首都とした(オスマン帝国の首都となったこの都市は、やがてイスタンブールと通称されるようになる)。17世紀の最大版図は、東西はアゼルバイジャンからモロッコに至り、南北はイエメンからウクライナ、ハンガリー、チェコスロバキアに至る広大な領域に及んだ。

アナトリア(小アジア)の片隅に生まれた小君侯国から発展したイスラム王朝であるオスマン朝は、やがて東ローマ帝国などの東ヨーロッパキリスト教諸国、マムルーク朝などの西アジア・北アフリカのイスラム教諸国を征服して地中海世界の過半を覆い尽くす世界帝国たるオスマン帝国へと発展した。

その出現は西欧キリスト教世界にとって「オスマンの衝撃」であり、15世紀から16世紀にかけてその影響は大きかった。宗教改革にも間接的ながら影響を及ぼし、神聖ローマ帝国のカール5世が持っていた西欧の統一とカトリック的世界帝国構築の夢を挫折させる主因となった。そして、「トルコの脅威」に脅かされた神聖ローマ帝国は「トルコ税」を新設、中世封建体制から絶対王政へ移行することになり、その促進剤としての役割を務めた[6]。ピョートル1世がオスマン帝国を圧迫するようになると、神聖ローマがロマノフ朝を支援して前線を南下させた。

19世紀中ごろに英仏が地中海規模で版図分割を実現した。オスマン債務管理局が設置された世紀末から、ドイツ帝国が最後まで残っていた領土アナトリアを開発した。このような経緯から、オスマン帝国は中央同盟国として第一次世界大戦に参戦し敗れた。敗戦後の講和条約のセーブル条約は列強によるオスマン帝国の解体といえる内容だったために同条約に反対する勢力が、アンカラに共和国政府を樹立し、1922年にはオスマン家のスルタン制度の廃止を宣言、メフメト6世は亡命した。1923年には「アンカラ政府」が「トルコ共和国」の建国を宣言し、1924年にはオスマン家のカリフ制度の廃止も宣言。結果、アナトリアの国民国家トルコ共和国に取って代わられた(トルコ革命)。

The Ottoman Empire (/ˈɒtəmən/; Ottoman Turkish: دولت عليه عثمانیه, Devlet-i ʿAlīye-i ʿOsmānīye, literally "The Exalted Ottoman State"; Modern Turkish: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu or Osmanlı Devleti), also historically known in Western Europe as the Turkish Empire[8] or simply Turkey,[9] was a state that controlled much of Southeast Europe, Western Asia and North Africa between the 14th and early 20th centuries. It was founded at the end of the 13th century in northwestern Anatolia in the town of Söğüt (modern-day Bilecik Province) by the Oghuz Turkish tribal leader Osman I.[10] After 1354, the Ottomans crossed into Europe, and with the conquest of the Balkans, the Ottoman beylik was transformed into a transcontinental empire. The Ottomans ended the Byzantine Empire with the 1453 conquest of Constantinople by Mehmed the Conqueror.[11]

During the 16th and 17th centuries, at the height of its power under the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent,[12] the Ottoman Empire was a multinational, multilingual empire controlling most of Southeast Europe, parts of Central Europe, Western Asia, parts of Eastern Europe and the Caucasus, North Africa and the Horn of Africa.[13] At the beginning of the 17th century, the empire contained 32 provinces and numerous vassal states. Some of these were later absorbed into the Ottoman Empire, while others were granted various types of autonomy during the course of centuries.[note 6]

With Constantinople as its capital and control of lands around the Mediterranean basin, the Ottoman Empire was at the centre of interactions between the Eastern and Western worlds for six centuries. While the empire was once thought to have entered a period of decline following the death of Suleiman the Magnificent, this view is no longer supported by the majority of academic historians.[14] The empire continued to maintain a flexible and strong economy, society and military throughout the 17th and much of the 18th century.[15] However, during a long period of peace from 1740 to 1768, the Ottoman military system fell behind that of their European rivals, the Habsburg and Russian empires.[16] The Ottomans consequently suffered severe military defeats in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, which prompted them to initiate a comprehensive process of reform and modernisation known as the Tanzimat. Thus, over the course of the 19th century, the Ottoman state became vastly more powerful and organised, despite suffering further territorial losses, especially in the Balkans, where a number of new states emerged.[17] The empire allied with Germany in the early 20th century, hoping to escape from the diplomatic isolation which had contributed to its recent territorial losses, and thus joined World War I on the side of the Central Powers.[18] While the Empire was able to largely hold its own during the conflict, it was struggling with internal dissent, especially with the Arab Revolt in its Arabian holdings. During this time, atrocities were committed by the Ottoman government against the Armenians, Assyrians and Pontic Greeks.[19]

The Empire's defeat and the occupation of part of its territory by the Allied Powers in the aftermath of World War I resulted in its partitioning and the loss of its Middle Eastern territories, which were divided between the United Kingdom and France. The successful Turkish War of Independence against the occupying Allies led to the emergence of the Republic of Turkey in the Anatolian heartland and the abolition of the Ottoman monarchy.[20]

L’Empire ottoman (turc ottoman : دولت عليه عثمانیه, Devlet-i ʿAlīye-i ʿOsmānīye, littéralement l'État ottoman exalté ; turc : Osmanlı İmparatorluğu ou Osmanlı Devleti ; connu historiquement en Europe de l'Ouest comme l'Empire turc3, Turquie ottomane4,5, ou simplement Turquie6), est un empire fondé à la fin du XIIIe siècle au nord-ouest de l'Anatolie, dans la commune de Söğüt (actuelle province de Bilecik), par le chef tribal oghouze, Osman Ier7. Après 1354, les Ottomans sont entrés en Europe, et, avec la conquête des Balkans, le Beylik ottoman s'est transformé en un empire trans-continental. Les Ottomans ont mis fin à l'Empire byzantin avec la conquête de Constantinople par Mehmed II, en 14538.

Aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles, à son apogée, sous le règne de Soliman le Magnifique, l'Empire ottoman était un empire multinational et multilingue contrôlant une grande partie de l'Europe du Sud-Est, des parties de l'Europe centrale, de l'Asie occidentale, du Caucase, de l'Afrique du Nord sauf le Royaume du Maroc et la Corne de l'Afrique9. Au début du XVIIe siècle, l'Empire comprenait trente-deux provinces et de nombreux États vassaux. Certains d'entre eux ont ensuite été absorbés par l'Empire ottoman, tandis que d'autres ont bénéficié de divers types d'autonomie au cours des sièclesa.

Avec Constantinople comme capitale, et le contrôle des terres autour du bassin méditerranéen, l'Empire ottoman fut au centre des interactions entre les mondes oriental et occidental pendant six siècles. Alors que l'on croyait autrefois que l'Empire était entré dans une période de déclin à la suite de la mort de Soliman le Magnifique, cette opinion n'est plus soutenue par la majorité des historiens universitaires. L'Empire a continué de maintenir une économie, une société et une armée puissantes et flexibles tout au long du XVIIe et d'une grande partie du XVIIIe siècle11,12,13. Les Ottomans subirent de graves défaites militaires à la fin du XVIIIe et au début du XIXe siècle, ce qui les amena à entamer un vaste processus de réforme et de modernisation connu sous le nom de Tanzimat. Ainsi, au cours du XIXe siècle, l'État ottoman est devenu beaucoup plus puissant et organisé malgré de nouvelles pertes territoriales, en particulier dans les Balkans où de nouveaux États ont émergé14. L'Empire s'est allié à l'Allemagne au début du XXe siècle, espérant échapper à l'isolement diplomatique qui avait contribué à ses récentes pertes territoriales, et s'engagea ainsi dans la Première Guerre mondiale du côté des puissances centrales15. Tandis que l'Empire était capable de tenir sa place pendant le conflit, il était en lutte avec la dissidence interne, en particulier dans ses possessions arabes, avec la révolte arabe de 1916-1918. Pendant ce temps, des exactions sont commises par le gouvernement ottoman, dont certaines de nature génocidaire contre les Arméniens16, les Assyriens, et les Grecs17.

La défaite de l'Empire et l'occupation d'une partie de son territoire par les puissances alliées au lendemain de la Première guerre mondiale entraînèrent sa partition, et la perte de ses territoires du Moyen-Orient divisés entre le Royaume-Uni et la France. Le succès de la guerre d'indépendance turque contre les occupants Alliés a conduit à l'émergence de la république de Turquie, dans le cœur de l'Anatolie, et à l'abolition de la monarchie ottomane18.

L'Impero ottomano o Sublime Stato ottomano, noto anche come Sublime porta (in lingua turca ottomana دَوْلَتِ عَلِيّهٔ عُثمَانِیّه, Devlet-i ʿAliyye-i ʿOsmâniyye; in turco moderno: Osmanlı Devleti o Osmanlı İmparatorluğu; in arabo: الدَّوْلَةُ العُثمَانِيَّة, al-Dawla al-ʿUthmāniyya), è stato un impero turco che è durato 623 anni, dal 1299 al 1922.

Fu detto "ottomano" poiché costituito originariamente dai successori di Osman Gazi, guerriero turco capostipite della dinastia ottomana, che assunse il titolo di sultano con il nome di Osman I. Il sultanato, e poi impero con Maometto II, nacque in continuità con il Sultanato selgiuchide di Rum e durò sino all'istituzione dell'odierna Repubblica di Turchia.

L'Impero ottomano fu uno dei più estesi e duraturi della storia: infatti durante il XVI e il XVII secolo, al suo apogeo sotto il regno di Solimano il Magnifico, era uno dei più potenti Stati del mondo, un impero multietnico, multiculturale e multilinguistico che si estendeva dai confini meridionali del Sacro Romano Impero alle periferie di Vienna e della Polonia a nord, fino allo Yemen e all'Eritrea a sud; dall'Algeria a ovest fino all'Azerbaigian a est, controllando gran parte dei Balcani, del Vicino Oriente e del Nordafrica.

Avendo Costantinopoli come capitale e un vasto controllo sulle coste del Mediterraneo, l'Impero fu al centro dei rapporti tra Oriente e Occidente per circa cinque secoli. Durante la prima guerra mondiale si alleò con gli Imperi centrali e con essi fu pesantemente sconfitto, tanto da essere smembrato per volontà dei vincitori.

El Imperio otomano, también conocido como Imperio turco otomano (en otomano: دولت عالیه عثمانیه Devlet-i Aliyye-i Osmâniyye; en turco moderno: Osmanlı Devleti o Osmanlı İmparatorluğu), fue un Estado multiétnico y multiconfesional gobernado por la dinastía osmanlí. Era conocido como el Imperio turco o Turquía por sus contemporáneos, aunque los gobernantes osmanlíes jamás utilizaron ese nombre para referirse a su Estado.

El Imperio otomano comenzó siendo uno más de los pequeños estados turcos que surgieron en Asia Menor durante la decadencia del Imperio selyúcida. Los turcos otomanos fueron controlando paulatinamente a los demás estados turcos, sobrevivieron a las invasiones mongolas y bajo el reinado de Mehmed II (1451-1481) acabaron con lo que quedaba del Imperio bizantino. La primera fase de la expansión otomana tuvo lugar bajo el gobierno de Osmán I (1288-1326) y siguió en los reinados de Orkhan, Murad I y Beyazid I, a expensas de los territorios del Imperio bizantino, Bulgaria y Serbia. Bursa cayó bajo su dominio en 1326 y Adrianópolis en 1361. Las victorias otomanas en los Balcanes alertaron a Europa occidental sobre el peligro que este Imperio representaba y fueron el motivo central de la organización de la Cruzada de Segismundo de Hungría. El sitio que pusieron los otomanos a Constantinopla fue roto gracias a Tamerlán, caudillo de los mongoles, quien tomó prisionero a Beyazid en 1402, pero el control mongol sobre los otomanos duró muy poco. Finalmente, el Imperio otomano logró conquistar Constantinopla en 1453.

En su máximo esplendor, entre los siglos XVI y XVII se expandía por tres continentes, ya que controlaba una vasta parte del Sureste europeo, el Medio Oriente y el norte de África: limitaba al oeste con el Sultanato de Marruecos, al este con Persia y el mar Caspio, al norte con el Zarato ruso, Dominios de los Habsburgo (Hungría y Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico) y la Mancomunidad de Polonia-Lituania, y al sur con Sudán, Eritrea, Somalia y el Emirato de Diriyah (Arabia). El Imperio otomano poseía 29 provincias, además de Moldavia, Transilvania, Valaquia y Crimea, que eran Estados vasallos.

El Imperio estuvo en el centro de las interacciones entre el Este y el Oeste durante seis siglos. Con Constantinopla como capital y el territorio que se conquistó bajo Solimán el Magnífico —correspondiente a las tierras gobernadas por Justiniano el Grande mil años antes—, el Imperio otomano era, en muchos aspectos, el sucesor islámico de los antiguos imperios clásicos. Numerosos rasgos y tradiciones culturales de estos (en campos como la arquitectura, la cocina, el ocio y el gobierno) fueron adoptados por los otomanos, quienes los elaboraron en nuevas formas. Estos rasgos culturales más tarde se mezclaron con las características de los grupos étnicos y religiosos que vivían dentro de los territorios otomanos y crearon una nueva y particular identidad cultural otomana.

Durante el siglo XIX, diversos territorios del Imperio otomano se independizaron, principalmente en Europa. Las sucesivas derrotas en guerras y el auge de los nacionalismos dentro del territorio llevaron al decaimiento del poder del imperio. Su participación en la Primera Guerra Mundial seguido con la ocupación de Constantinopla y el surgimiento de movimientos revolucionarios dentro de Turquía le dieron el golpe mortal y resultó en la partición del Imperio otomano. El Imperio bajo la dirección de un sultán fue abolido el 1 de noviembre de 1922 y un año después, el califato. Los movimientos revolucionarios que lo habían derrocado se agruparon y fundaron el 23 de octubre de 1923 la República de Turquía.

Осма́нская импе́рия (осман. دولت عالیه عثمانیه — Devlet-i Âliyye-i Osmâniyye[4]), также Оттома́нская империя, Оттома́нская По́рта или просто По́рта[5] — государство, созданное в 1299 году турками-османами под предводительством удж-бея Османа Гази на северо-западе Малой Азии[6].

После падения Византии в 1453 году Османское государство превратилось в империю и стало султанатом. Падение Константинополя явилось важнейшим событием в развитии турецкой государственности, так как после 1453 года Османская империя окончательно закрепилась в Европе, что является важной характеристикой современной Турции. Правление османской династии длилось 623 года, с 27 июля[7][прим. 1] 1299 года по 1 ноября 1922 го�

Das Byzantinische Reich, verkürzt auch nur Byzanz, oder – aufgrund der historischen Herkunft – das Oströmische Reich bzw. Ostrom war ein Kaiserreich im östlichen Mittelmeerraum. Es entstand im Verlauf der Spätantike nach der so genannten Reichsteilung von 395 aus der östlichen Hälfte des Römischen Reiches. Das von der Hauptstadt Konstantinopel – auch „Byzanz“ genannt – aus regierte Reich erstreckte sich während seiner größten Ausdehnung Mitte des sechsten Jahrhunderts von Italien und der Balkanhalbinsel bis zur Arabischen Halbinsel und nach Nordafrika, war aber seit dem siebten Jahrhundert weitgehend auf Kleinasien und Südosteuropa beschränkt. Mit der Eroberung von Konstantinopel durch die Osmanen im Jahr 1453 endete das Reich.

Die Geschichte des Byzantinischen Reiches war von einem Abwehrkampf an den Grenzen gegen äußere Feinde geprägt, der die Kräfte des Reiches erheblich beanspruchte. Dabei wechselten sich bis in die Spätzeit, als das Reich keine ausreichenden Ressourcen mehr hatte, Phasen der Expansion (nach Gebietsverlusten im siebten Jahrhundert Eroberungen im zehnten und elften Jahrhundert) mit Phasen des Rückzugs ab. Im Inneren kam es (besonders bis ins neunte Jahrhundert) immer wieder zu unterschiedlich stark ausgeprägten theologischen Auseinandersetzungen sowie zu vereinzelten Bürgerkriegen, doch blieb das an römischen Strukturen orientierte staatliche Fundament bis ins frühe 13. Jahrhundert weitgehend intakt. Kulturell hat Byzanz der Moderne bedeutende Werke aus Literatur und Kunst hinterlassen. Byzanz spielte auch aufgrund des stärker bewahrten antiken Erbes eine wichtige Mittlerrolle. Hinsichtlich der Christianisierung Osteuropas, bezogen auf den Balkanraum und Russland, war der byzantinische Einfluss ebenfalls von großer Bedeutung.

—— 拜占庭的起源 ——

拜占庭之名原起于一座靠海的古希腊移民城市,公元 330年罗马皇帝君士坦丁一世在此建城,作为罗马帝国的陪都,并改名为君士坦丁堡。君士坦丁堡位于连接黑海到爱琴海之间的战略水道博斯普鲁斯海峡,扼制海 陆商业要道,地理位置十分优越。公元395年庞大的罗马帝国饱受各路蛮族侵扰,为便于管辖而将帝国一分为二,东部帝国即以君士坦丁堡为首府,因此东罗马帝 国又称为拜占庭帝国。

公元476年西罗马帝国在经历了包括匈奴和诸多日尔曼部落的反复侵袭之后终于咽下了最后一口气,拜占庭遂成为唯一的罗马人帝国——实际上他们一直以纯正罗马血统自居。

—— 战争和衰弱 ——

公元527年,拜占庭迎来了第一位强势的皇帝——查士丁尼一世。其随即任命名将贝利萨留为元帅,向夙敌波斯帝国宣战。公元528年波斯 军大将扎基西斯率3万大军,于次年在尼亚比斯以压倒性兵力逼退贝利萨留,隔年双方军队在两河流域的德拉城再次会战,贝利萨留的军队少到可怜……但波斯军队 犯了愚蠢的错误,他们背城列阵而且要命的是背的不是自己的城,于是多于对手数倍且装备精良的波斯军理所当然(或者匪夷所思)地惨败……随后波斯军一败再 败,但还是于531年卡尔基斯阻挡了贝利萨留的前进步伐,两国终于532年签下停战协议。随后雄心勃勃的查士丁尼再跟达尔旺人开战,贝利萨留出征非洲,可 怜的拜占庭远征军步骑兵总数连马都算上才2万还多个零头!更要命的是其中还包括了大半粗鲁且毫无组织纪律性可言的蛮族雇佣兵。搭船出海取道伯罗奔尼撒、途 经西西里一路磕磕碰碰,直到9月初才踏上非洲大地的贝利萨留不仅不知对手的实力到底是1万还是100万甚至连个详细点的地图都无,幸好当地愿意当向导赚小 费的人还算不少,贝利萨留终于在9月中旬在迦太基撞上达尔旺人的大军。人说强龙难压地头蛇,但贝利萨留却敢于在地头蛇门口大玩迷踪步,一番错综复杂的迂回 使达尔旺人的军队失去了有利地形并分散做几部失去了衔接,惨遭和当年的波斯军同样的命运。外强中干的达尔旺人此后再也没组织起任何一次较像样的反击,终于 534年3月投降,达尔旺王国灭亡。查士丁尼的非洲战役使拜占庭帝国控制了非洲广大的畜牧基地。 (Quelle:games.sina.com.cn/talk/0212/120913641.shtml)

拜占庭帝国是历史上一个著名的帝国。罗马帝国东西分治后,帝国东部延续被称为东罗马帝国(相对于帝国西部的西罗马帝国)。16世纪以后,开始有学者称之为“拜占庭帝国”,被视为新政权。其国民在帝国一千多年的期间仍自称为“罗马帝国”的公民(拉丁语:Imperium Romanum;希腊语:Βασιλεία Ρωμαίων)。帝国位于欧洲东南部,领土曾包括欧亚非三大洲的亚洲西部和非洲北部,是古典时代和中世纪欧洲历史上最悠久的君主制国家。

拜占庭帝国共历经12个王朝及93位皇帝,首都为新罗马(拉丁语:Nova Roma;希腊语:Νέα Ρώμη,即君士坦丁堡)。其疆域在11个世纪中不断变动。色雷斯、希腊和小亚细亚西部是帝国的核心地区;今日的土耳其、希腊、保加利亚、马其顿、阿尔巴尼亚从4世纪至13世纪是帝国领土的主要组成部分;意大利和原南斯拉夫的大部、伊比利亚半岛南部、叙利亚、巴勒斯坦、埃及、利比亚、突尼斯、今阿特拉斯山脉以北的阿尔及利亚和今天摩洛哥的丹吉尔也在7世纪之前曾是帝国的国土。

关于帝国的起始纪年,历史学界仍存有争议。主流观点认为,330年君士坦丁大帝建立新罗马、罗马帝国政治中心东移,是东罗马帝国成立的标志。德国东罗马学者斯坦因以戴克里先皇帝即位(284年;这位皇帝首次将罗马帝国分为东西两半分治)为东罗马帝国的起始纪年。其他观点分别以476年(西罗马帝国灭亡)、527年(查士丁尼一世登基)、7世纪(希腊化开始)和8世纪(希腊化完成)为东罗马帝国起始的标志。

东罗马帝国本为罗马帝国的东半部,较为崇尚希腊文化,与西罗马帝国分裂后,更逐渐发展为以希腊文化、希腊语和及后的东正教为立国基础,在620年,希拉克略皇帝首次让希腊语取代拉丁语,成为帝国的官方语言,使得东罗马帝国成为不同于古罗马和西罗马帝国的国家。在476年西罗马帝国灭亡前和神圣罗马帝国成立后,这个帝国被外人称为“东罗马帝国”,尽管其正式国号仍延续着古罗马帝国时期的国号。直到1557年德意志历史学家赫罗尼姆斯·沃尔夫为了区分其帝国的古罗马时期及神圣罗马帝国而引入了“拜占庭帝国”作为称呼,并被现代史学上所使用。

东罗马帝国的文化和宗教对于今日的东欧各国有很大的影响。此外,帝国在其十一个世纪的悠久历史中所保存下来的古典希腊和罗马史料、著作,以及理性的哲学思想,也为中世纪欧洲突破天主教会神权束缚提供了最直接的动力,引发了文艺复兴运动,并深远地影响了人类历史。

1204年4月13日,东罗马帝国首都君士坦丁堡曾被第四次十字军东征攻陷和劫掠,直到1261年收复。1453年5月29日,奥斯曼帝国攻陷了首都君士坦丁堡,末代皇帝君士坦丁十一世战死,历时一千余年的东罗马帝国就此灭亡,长达1480年的罗马帝国也正式终结。

東ローマ帝国(ひがしローマていこく、英語: Eastern Roman Empire[3])またはビザンツ帝国、ビザンティン帝国は、東西に分割統治されて以降のローマ帝国の東側の領域、国家である。ローマ帝国の東西分割統治は4世紀以降断続的に存在したが、一般的には最終的な分割統治が始まった395年以降の東の皇帝の統治領域を指す。西ローマ帝国の滅亡後の一時期は旧西ローマ領を含む地中海の広範な地域を支配したものの、8世紀以降はバルカン半島、アナトリア半島を中心とした国家となった。首都はコンスタンティノポリス(現在のトルコ共和国の都市であるイスタンブール)であった。

西暦476年に西ローマ帝国がゲルマン人の傭兵隊長オドアケルによって滅ぼされた際、形式上は最後の西ローマ皇帝ロムルス・アウグストゥスが当時の東ローマ皇帝ゼノンに帝位を返上して東西の帝国が「再統一」された(オドアケルは帝国の西半分の統治権を代理するという体裁をとった)ため、当時の国民は自らを古代のローマ帝国と一体のものと考えていた。また、ある程度の時代が下ると民族的・文化的にはギリシャ化が進んでいったことから、同時代の西欧からは「ギリシア帝国」とも呼ばれた。

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire and Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinople (modern-day Fatih, İstanbul, and formerly Byzantium). It survived the fragmentation and fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD and continued to exist for an additional thousand years until it fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.[2] During most of its existence, the empire was the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in Europe. Both the terms "Byzantine Empire" and "Eastern Roman Empire" are historiographical exonyms; its citizens continued to refer to their empire simply as the Roman Empire (Greek: Βασιλεία Ῥωμαίων, tr. Basileia Rhōmaiōn; Latin: Imperium Romanum),[3] or Romania (Ῥωμανία), and to themselves as "Romans".[4]

Several signal events from the 4th to 6th centuries mark the period of transition during which the Roman Empire's Greek East and Latin West diverged. Constantine I (r. 324–337) reorganised the empire, made Constantinople the new capital, and legalised Christianity. Under Theodosius I (r. 379–395), Christianity became the Empire's official state religion and other religious practices were proscribed. Finally, under the reign of Heraclius (r. 610–641), the Empire's military and administration were restructured and adopted Greek for official use in place of Latin.[5] Thus, although the Roman state continued and its traditions were maintained, modern historians distinguish Byzantium from ancient Rome insofar as it was centred on Constantinople, oriented towards Greek rather than Latin culture, and characterised by Orthodox Christianity.[4]

The borders of the empire evolved significantly over its existence, as it went through several cycles of decline and recovery. During the reign of Justinian I (r. 527–565), the Empire reached its greatest extent after reconquering much of the historically Roman western Mediterranean coast, including North Africa, Italy, and Rome itself, which it held for two more centuries. The Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 exhausted the empire's resources and contributed to major territorial losses during the Early Muslim conquests of the 7th century wherein it lost its richest provinces, Egypt and Syria, to the Arabs.[6] During the Macedonian dynasty (10th–11th centuries), the empire expanded again and experienced the two-century long Macedonian Renaissance, which came to an end with the loss of much of Asia Minor to the Seljuk Turks after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. This battle opened the way for the Turks to settle in Anatolia.

The empire recovered again during the Komnenian restoration, and by the 12th century Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest European city.[7] However, it was delivered a mortal blow during the Fourth Crusade, when Constantinople was sacked in 1204 and the territories that the empire formerly governed were divided into competing Byzantine Greek and Latin realms. Despite the eventual recovery of Constantinople in 1261, the Byzantine Empire remained only one of several small rival states in the area for the final two centuries of its existence. Its remaining territories were progressively annexed by the Ottomans over the 14th and 15th century. The Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 finally ended the Byzantine Empire.[8] The last of the imperial Byzantine successor states, the Empire of Trebizond, would be conquered by the Ottomans eight years later in the 1461 Siege of Trebizond.[9]

L’Empire byzantin ou Empire romain d'Orient désigne la civilisation apparue vers le IVe siècle dans la partie orientale de l'Empire romain, au moment où celui-ci se divise progressivement en deux.

L’Empire byzantin se caractérise par sa longévité. Il puise ses origines dans la fondation même de Rome, et la datation de ses débuts change selon les critères choisis par chaque historien. La fondation de Constantinople, sa capitale, par Constantin Ier en 330, autant que la division d’un Empire romain de plus en plus difficile à gouverner et qui devient définitive en 395, sont parfois citées. Quoi qu’il en soit, plus dynamique qu’un monde romain occidental brisé par les invasions barbares, l’Empire d’Orient s’affirme progressivement comme une construction politique originale. Indubitablement romain, cet Empire est aussi chrétien et de langue principalement grecque. À la frontière entre l’Orient et l’Occident, mêlant des éléments provenant directement de l’Antiquité avec des aspects innovants dans un Moyen Âge parfois décrit comme grec, il devient le siège d’une culture originale qui déborde bien au-delà de ses frontières, lesquelles sont constamment assaillies par des peuples nouveaux. Tenant d’un universalisme romain, il parvient à s’étendre sous Justinien (empereur de 527 à 565), retrouvant une partie des antiques frontières impériales, avant de connaître une profonde rétractation. C’est à partir du VIIe siècle que de profonds bouleversements frappent l’Empire byzantin. Contraint de s’adapter à un monde nouveau dans lequel son autorité universelle est contestée, il rénove ses structures et parvient, au terme d’une crise iconoclaste, à connaître une nouvelle vague d’expansion qui atteint son apogée sous Basile II (qui règne de 976 à 1025). Les guerres civiles autant que l’apparition de nouvelles menaces forcent l'Empire à se transformer à nouveau sous l'impulsion des Comnènes avant d’être disloqué par la quatrième croisade lorsque les croisés s'emparent de Constantinople en 1204. S’il renaît en 1261, c’est sous une forme affaiblie qui ne peut résister aux envahisseurs ottomans et à la concurrence économique des républiques italiennes (Gênes et Venise). La chute de Constantinople en 1453 marque sa fin.

Tout au long de son histoire millénaire, une continuité autant que des ruptures rythment l’existence de l’Empire byzantin, objet complexe à analyser dans sa diversité. Héritier d’une riche culture gréco-romaine, il la fait vivre et contribue à la transmettre à l’Occident au moment de la Renaissance. Il développe sa propre civilisation, profondément empreinte de religiosité. Pilier du monde chrétien, il est le défenseur d’un christianisme dit orthodoxe qui rayonne dans l’Europe centrale et orientale où son héritage est encore vivace aujourd’hui, tandis que la séparation des Églises d'Orient et d'Occident inaugure une rupture progressive avec le catholicisme romain.

Qualifié d’« archaïque » ou de « déclinant » dans l’historiographie ancienne, parfois empreinte de mishellénisme, l’Empire byzantin a fait preuve d’une remarquable capacité d’adaptation face aux évolutions du monde qui l’entoure et aux menaces qui l’assaillent constamment, souvent sur plusieurs fronts. Il parvient souvent habilement à user de la diplomatie autant que de la force pour contenir ses ennemis. Sa situation exceptionnelle, au carrefour entre l'Orient et l'Occident dont il contribue à brouiller les frontières, entre monde méditerranéen et bassin pontique, lui permet de développer une économie dynamique, symbolisée par sa monnaie, souvent utilisée bien au-delà de ses frontières. Cette même abondance suscite aussi les convoitises de voisins ambitieux qui se heurtent régulièrement aux puissantes murailles de Constantinople. Celle-ci, plus encore que Rome avec l’Empire romain antérieur, est le centre du monde byzantin. Même au moment de son déclin à partir de 1204, il préserve une vivacité culturelle qui favorise l’émergence de la Renaissance européenne.

Les jugements sur l’Empire byzantin ont profondément varié en fonction des époques. D’un exemple à suivre pour les régimes absolutistes du XVIIe siècle, il est vivement dénoncé en raison même de cet absolutisme et décrit comme décadent au XVIIIe siècle. Ces interprétations ont laissé place à des perspectives historiques plus scientifiques. L’héritage du monde byzantin est cardinal dans la compréhension du monde slave, auquel il a laissé un alphabet et une religion. Au-delà, il a su rayonner, transmettant un droit romain codifié, des chefs d’œuvre architecturaux incarnés par la basilique Sainte-Sophie et, plus largement, une culture originale.

Impero bizantino (395 d.C. - 1453) è il nome con cui gli studiosi moderni e contemporanei indicano l'Impero romano d'Oriente (termine che iniziò a diffondersi durante il regno dell'imperatore Valente), di cultura prevalentemente greca, separatosi dalla parte occidentale, di cultura quasi esclusivamente latina, dopo la morte di Teodosio I nel 395.

Il termine "bizantino" è stato introdotto solo a partire dal XVIII secolo dagli Illuministi, quando l'Impero Romano d'Oriente era ormai scomparso da circa tre secoli. "Romei" (dal greco: Ῥωμιός / Rōmiós) era il termine usato dagli stessi abitanti dell'Impero Romano d'Oriente per definirsi. Come l'Impero bizantino era di fatto Impero romano, così la sua capitale Costantinopoli era la Nuova Roma e così pure il titolo dei suoi sovrani era Basileús kaì Kaìsar ton romaíon (greco: Βασιλεὺς καὶ Καῖσαρ τῶν Ῥωμαίων), ovvero Sovrano e Cesare dei Romani. La stessa Penisola balcanica veniva chiamata dai Romei, Rumelia, nome di regione che sarà conservato pure dai conquistatori ottomani. Gli stessi ottomani utilizzeranno la parola Rūm (in arabo: الرُّومُ, al-Rūm), termine storicamente impiegato dai musulmani per indicare i Bizantini. I sultani ottomani, dopo la conquista di Costantinopoli, si assegneranno il titolo onorifico di qaysar-ı Rum, "Cesare dei Romani", mantenendo il nome di Qusṭanṭīniyya, fino al XX secolo, per la nuova capitale, che sostituiva l'antica anatolica Edirne (Adrianopolis).

Tuttavia per distinguerlo dall'Impero romano d'Occidente, si è preferito assegnare alla parte orientale il nome di "Impero bizantino". Non c'è accordo fra gli storici sulla data in cui si dovrebbe cessare di utilizzare il termine "romano" per sostituirlo con il termine "bizantino", anche perché entrambe le definizioni sono utilizzate da molti di loro, spesso indistintamente, per designare il mondo romano-orientale fino almeno al VII secolo. Le diverse impostazioni storiografiche condizionano anche la diversità di opinioni nella determinazione della datazione: taluni lo fanno coincidere con il 395 (separazione definitiva dei due imperi), ma si è anche proposto il 476 (fine dell'Impero Romano d'Occidente), il 330 (anno di inaugurazione della Nova Roma o Νέα Ῥώμη, fondata da Costantino I, copia fedele e nostalgica della prima Roma), il 565 (morte di Giustiniano I, ultimo imperatore di madrelingua latina e del suo sogno della Restauratio imperii). Alcuni storici prolungano il periodo propriamente "romano" fino al 610, anno dell'ascesa al trono di Eraclio I il quale modificò notevolmente la struttura dell'Impero, rendendo il greco lingua ufficiale al posto del latino.

Resta comunque il fatto che per gli imperatori bizantini e per i propri sudditi il loro impero si identificò sempre con quello di Augusto e Costantino I dal momento che "romano" e "greco" fino al XVIII secolo furono per essi sinonimi.

L'impero, dopo una lunga crisi, la sua distruzione da parte dei crociati nel 1204 e la sua restaurazione nel 1261, cessò definitivamente di esistere nel 1453 (conquista di Costantinopoli da parte dei Turchi ottomani guidati da Maometto II).

El Imperio bizantino o Bizancio fue la parte oriental del Imperio romano que pervivió durante toda la Edad Media y el comienzo del Renacimiento. Este imperio se ubicaba en el Mediterráneo oriental. Su capital se encontraba en Constantinopla (en griego: Κωνσταντινούπολις, actual Estambul), cuyo nombre más antiguo era Bizancio, importante ciudad de la Tracia griega fundada en el 650 a. C. También se conoce al Imperio bizantino como Imperio romano de Oriente, especialmente para hacer referencia a sus primeros siglos de existencia, durante la Antigüedad tardía, época en que el Imperio romano de Occidente todavía existía. Dado que el Imperio romano había establecido que la lengua en todo el territorio debía ser el griego, los historiadores en general coinciden en señalar que el Imperio bizantino fue un imperio griego en alianza política con Roma.23

A lo largo de su dilatada historia, el Imperio bizantino sufrió numerosos reveses y pérdidas de territorio, especialmente durante las guerras romano-sasánidas, guerras bizantino-normandas y las guerras árabo-bizantinas. Aunque su influencia en África del Norte y Oriente Próximo había entrado en declive como resultado de estos conflictos, continuó siendo una importante potencia militar y económica en Europa, Oriente Próximo y el Mediterráneo oriental durante la mayor parte de la Edad Media. Tras una última recuperación de su pasado poder durante la época de la dinastía Comneno, en el siglo XII, el Imperio comenzó una prolongada decadencia durante las guerras otomano-bizantinas que culminó con la toma de Constantinopla y la conquista del resto de los territorios bajo dominio bizantino por los turcos, en el siglo XV.

Durante su milenio de existencia, el Imperio fue un bastión del cristianismo, e impidió el avance del islam hacia Europa Occidental. Fue uno de los principales centros comerciales del mundo, estableciendo una moneda de oro estable que circuló por toda el área mediterránea. Influyó de modo determinante en las leyes, los sistemas políticos y las costumbres de gran parte de Europa y de Oriente Medio, y gracias a él se conservaron y transmitieron muchas de las obras literarias y científicas del mundo clásico y de otras culturas.

En tanto que es la continuación de la parte oriental del Imperio romano, su transformación en una entidad cultural diferente de Occidente puede verse como un proceso que se inició cuando el emperador Constantino I el Grande trasladó la capital a la antigua Bizancio (que entonces rebautizó como Nueva Roma, y más tarde se denominaría Constantinopla); continuó con la escisión definitiva del Imperio romano en dos partes tras la muerte de Teodosio I, en 395, y la posterior caída en 476 del Imperio romano de Occidente; y alcanzó su culminación durante el siglo VII, bajo el emperador Heraclio I, con cuyas reformas (sobre todo, la reorganización del ejército y la adopción del griego como lengua oficial), el Imperio adquirió un carácter marcadamente diferente al del viejo Imperio romano. Algunos académicos, como Theodor Mommsen, han afirmado que hasta Heraclio puede hablarse con propiedad del Imperio romano de Oriente y más adelante de Imperio bizantino, que duró hasta 1453, ya que Heraclio sustituyó el antiguo título imperial de «augusto» por el de basileus (palabra griega que significa 'rey' o 'emperador') y reemplazó el latín por el griego como lengua administrativa en 620, después de lo cual el Imperio tuvo un marcado carácter helénico.

En todo caso, el término Imperio bizantino fue creado por la erudición ilustrada de los siglos XVII y XVIII y nunca fue utilizado por los habitantes de este imperio, que prefirieron denominarlo siempre Imperio romano (griego: Βασιλεία Ῥωμαίων, Basileia Rhōmaiōn; latín: Imperium Romanum) o Romania (Ῥωμανία) durante toda su existencia.

Византи́я, Византи́йская импе́рия, Восто́чная Ри́мская импе́рия, самоназвание Держава Ромеев, Ромейская империя (395[~ 2]—1453) — государство, сформировавшееся в 395 году вследствие давления гуннов на Римскую империю, после смерти императора Феодосия I, распавшееся на западную и восточную части. Чуть больше чем через восемьдесят лет после раздела Западная Римская империя прекратила своё существование, оставив Византию исторической, культурной и цивилизационной преемницей Древнего Рима на протяжении почти десяти столетий истории Поздней Античности и Средневековья[1][2].

Бессменной столицей и цивилизационным центром Византийской империи был Константинополь[3], один из крупнейших городов средневекового мира V—XII вв. Наибольшие владения империя контролировала при императоре Юстиниане I (527—565), вернув себе на несколько десятилетий значительную часть прибрежных территорий бывших западных провинций Рима и положение самой могущественной средиземноморской державы. В дальнейшем под натиском многочисленных врагов государство постепенно утрачивало земли. После славянских, лангобардских, вестготских и арабских завоеваний империя занимала лишь территорию Греции и Малой Азии. Некоторое усиление в IX—XI веках сменилось серьёзными потерями в конце XI века, во время нашествия сельджуков, и поражения при Манцикерте, усилением при первых Комнинах, после распада страны под ударами крестоносцев, взявших Константинополь в 1204 году, очередным усилением при Иоанне Ватаце, восстановлением империи Михаилом Палеологом, и, наконец, окончательной гибелью в середине XV века под натиском османов.

Der Bosporus (griechisch Βόσπορος „Rinderfurt“, von βοῦς boũs „Rind, Ochse“ und πόρος póros „Weg, Furt“; türkisch Boğaz „Schlund“, bzw. Karadeniz Boğazı für „Schlund des Schwarzen Meeres“; veraltet „Straße von Konstantinopel“) ist eine Meerenge zwischen Europa und Kleinasien, die das Schwarze Meer (in der Antike: Pontos Euxeinos) mit dem Marmarameer (in der Antike: Propontis) verbindet; daher stellt er einen Abschnitt der südlichen Innereurasischen Grenze dar. Auf seinen beiden Seiten befindet sich die Stadt Istanbul, deren Geografie er maßgeblich prägt. Der Bosporus hat eine Länge von ca. 30 Kilometern und eine Breite von 700 bis 2500 Metern. In der Mitte variiert die Tiefe zwischen 36 und 124 Metern (bei Bebek). Innerhalb des Bosporus liegt auf der westlichen Seite das Goldene Horn, eine langgezogene Bucht und ein seit langem genutzter natürlicher Hafen.

Die Durchfahrtsrechte für die internationale Schifffahrt wurden 1936 im Vertrag von Montreux geregelt.

*Mittelmeer

*Mittelmeer

Ägypten

Ägypten

Albanien

Albanien

Algerien

Algerien

Bernsteinstraße

Bernsteinstraße

Bosnien-Herzegowina

Bosnien-Herzegowina

Frankreich

Frankreich

Gibraltar

Gibraltar

Griechenland

Griechenland

Israel

Israel

Italien

Italien

Kroatien

Kroatien

Libanon

Libanon

Libyen

Libyen

Malta

Malta

Malta

Malta

Monaco

Monaco

Montenegro

Montenegro

Palästina

Palästina

Slowenien

Slowenien

Spanien

Spanien

Syrien

Syrien

Tunesien

Tunesien

Türkei

Türkei

Zypern

Zypern

Das Mittelmeer (lateinisch Mare Mediterraneum,[1] deshalb deutsch auch Mittelländisches Meer, präzisierend Europäisches Mittelmeer, im Römischen Reich Mare Nostrum) ist ein Mittelmeer zwischen Europa, Afrika und Asien, ein Nebenmeer des Atlantischen Ozeans und, da es mit der Straße von Gibraltar nur eine sehr schmale Verbindung zum Atlantik besitzt, auch ein Binnenmeer. Im Arabischen und Türkischen wird es auch als „Weißes Meer“ (البحر الأبيض/al-baḥr al-abyaḍ bzw. türk. Akdeniz) bezeichnet.

Zusammen mit den darin liegenden Inseln und den küstennahen Regionen Südeuropas, Vorderasiens und Nordafrikas bildet das Mittelmeer den Mittelmeerraum, der ein eigenes Klima (mediterranes Klima) hat und von einer eigenen Flora und Fauna geprägt ist.

地中海(英文:Mediterranean),被北面的欧洲大陆、南面的非洲大陆以及东面的亚洲大陆包围着。东西长约4000千米,南北最宽处大约为1800千米,面积251.6万平方千米,是地球上最大的陆间海。地中海的平均深度是1500米,最深处为5267米。

地中海西部通过直布罗陀海峡与大西洋相接,东部通过土耳其海峡(达达尼尔海峡和博斯普鲁斯海峡、马尔马拉海)和黑海相连。19世纪时开通的苏伊士运河,接通了地中海与红海。地中海是世界上最古老的海之一[3],而其附属的大西洋却是年轻的海洋。地中海处在欧亚板块和非洲板块交界处,是世界最强地震带之一。地中海地区有维苏威火山、埃特纳火山。

地中海作为陆间海,风浪较小,加之沿岸海岸线曲折、岛屿众多,拥有许多天然良好的港口,成为沟通三个大陆的交通要道。这样的条件,使地中海从古代开始海上贸易就很繁盛,促进了古代古埃及文明、古希腊文明、罗马帝国等的发展。现在也是世界海上交通的重要地区之一。其沿岸的腓尼基人、克里特人、希腊人,以及后来的葡萄牙人和西班牙人都是航海业发达的民族。著名的航海家如哥伦布、达·伽马、麦哲伦等,都出自地中海沿岸的国家。

地中海沿岸夏季炎热干燥,冬季温暖湿润,被称作地中海性气候。植被,叶质坚硬,叶面有蜡质,根系深,有适应夏季干热气候的耐旱特征,属亚热带常绿硬叶林。这里光热充足,是欧洲主要的亚热带水果产区,盛产柑橘、无花果,和葡萄等,还有木本油料作物油橄榄。

地中海(ちちゅうかい、ラテン語: Mare Mediterraneum)は、北と東をユーラシア大陸、南をアフリカ大陸(両者で世界島)に囲まれた地中海盆地に位置する海である。面積は約3000平方キロメートル、平均水深は約1500メートル[2]。海洋学上の地中海の一つ。

地中海には、独立した呼称を持ついくつかの海域が含まれる(エーゲ海、アドリア海など)。地中海と接続する他の海としては、ジブラルタル海峡の西側に大西洋が、ダーダネルス海峡を経た北東にマルマラ海と黒海があり、南西はスエズ運河で紅海と結ばれている(「海域」「地理」で詳述)。

北岸の南ヨーロッパ、東岸の中近東、南岸の北アフリカは古代から往来が盛んで、「地中海世界」と総称されることもある[3]。

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa and on the east by the Levant. Although the sea is sometimes considered a part of the Atlantic Ocean, it is usually identified as a separate body of water. Geological evidence indicates that around 5.9 million years ago, the Mediterranean was cut off from the Atlantic and was partly or completely desiccated over a period of some 600,000 years, the Messinian salinity crisis, before being refilled by the Zanclean flood about 5.3 million years ago.

It covers an approximate area of 2.5 million km2 (965,000 sq mi), but its connection to the Atlantic (the Strait of Gibraltar) is only 14 km (8.7 mi) wide. The Strait of Gibraltar is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Gibraltar and Spain in Europe from Morocco in Africa. In oceanography, it is sometimes called the Eurafrican Mediterranean Sea or the European Mediterranean Sea to distinguish it from mediterranean seas elsewhere.[2][3]

The Mediterranean Sea has an average depth of 1,500 m (4,900 ft) and the deepest recorded point is 5,267 m (17,280 ft) in the Calypso Deep in the Ionian Sea. The sea is bordered on the north by Europe, the east by Asia, and in the south by Africa. It is located between latitudes 30° and 46° N and longitudes 6° W and 36° E. Its west-east length, from the Strait of Gibraltar to the Gulf of Iskenderun, on the southwestern coast of Turkey, is approximately 4,000 km (2,500 miles). The sea's average north-south length, from Croatia’s southern shore to Libya, is approximately 800 km (500 miles). The Mediterranean Sea, including the Sea of Marmara (connected by the Dardanelles to the Aegean Sea), has a surface area of approximately 2,510,000 square km (970,000 square miles).[4]

The sea was an important route for merchants and travellers of ancient times that allowed for trade and cultural exchange between emergent peoples of the region. The history of the Mediterranean region is crucial to understanding the origins and development of many modern societies.

The countries surrounding the Mediterranean in clockwise order are Spain, France, Monaco, Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco; Malta and Cyprus are island countries in the sea. In addition, the Gaza Strip and the British Overseas Territories of Gibraltar and Akrotiri and Dhekelia have coastlines on the sea.

La mer Méditerranée (prononcé [me.di.tɛ.ʁa.ne]) est une mer intercontinentale presque entièrement fermée, bordée par les côtes d'Europe du sud, d’Afrique du Nord et d’Asie, depuis le détroit de Gibraltar à l'ouest aux entrées des Dardanelles et du canal de Suez à l'est. Elle s’étend sur une superficie d’environ 2,5 millions de kilomètres carrés. Son ouverture vers l’océan Atlantique par le détroit de Gibraltar est large de 14 kilomètres.

Elle doit son nom au fait qu’elle est littéralement une « mer au milieu des terres », en latin « mare medi terra »1.

Durant l’Antiquité, la Méditerranée était une importante voie de transports maritimes permettant l’échange commercial et culturel entre les peuples de la région — les cultures mésopotamiennes, égyptienne, perse, phénicienne, carthaginoise, berbère, grecque, arabe (conquête musulmane), ottomane, byzantine et romaine. L’histoire de la Méditerranée est importante dans l’origine et le développement de la civilisation occidentale.

Il mar Mediterraneo, detto brevemente Mediterraneo, è un mare intercontinentale situato tra Europa, Nordafrica e Asia occidentale connesso all'Oceano Atlantico. La sua superficie approssimativa è di 2,51 milioni di km² e ha uno sviluppo massimo lungo i paralleli di circa 3 700 km. La lunghezza totale delle sue coste è di 46 000 km, la profondità media si aggira sui 1 500 m, mentre quella massima è di 5 270 m presso le coste del Peloponneso. La salinità media si aggira dal 36,2 al 39 ‰.[2] La popolazione presente negli stati bagnati dalle sue acque ammonta a circa 450 milioni di persone.[2].

El mar Mediterráneo es uno de los mares del Atlántico. Está rodeado por la región mediterránea, comprendida entre Europa meridional, Asia Occidental y África septentrional. Fue testigo de la evolución de varias civilizaciones como los egipcios, los fenicios, hebreos, griegos, cartagineses, romanos, etc. Con aproximadamente 2,5 millones de km² y 3.860 km de longitud, es el segundo mar interior más grande del mundo, después del Caribe.1 Sus aguas, que bañan las tres penínsulas del sur de Europa (Ibérica, Itálica, Balcánica) y una de Asia (Anatolia), comunican con el océano Atlántico a través del estrecho de Gibraltar, con el mar Negro por los estrechos del Bósforo y de los Dardanelos y con el mar Rojo por el canal de Suez.2 Es el mar con las tasas más elevadas de hidrocarburos y contaminación del mundo.3

Средизе́мное мо́ре — межматериковое море, по происхождению представляющее собой глубоководную псевдоабиссальную внутришельфовую депрессию[1][2], связанную на западе с Атлантическим океаном Гибралтарским проливом[3].

В Средиземном море выделяют, как его составные части, моря: Адриатическое, Альборан, Балеарское, Ионическое, Кипрское, Критское, Левантийское, Ливийское, Лигурийское, Тирренское и Эгейское. В бассейн Средиземного моря также входят Мраморное, Чёрное и Азовское моря.

Geographie

Geographie

Trentino-Alto Adige

Trentino-Alto Adige

Veneto

Veneto

Toscana

Toscana

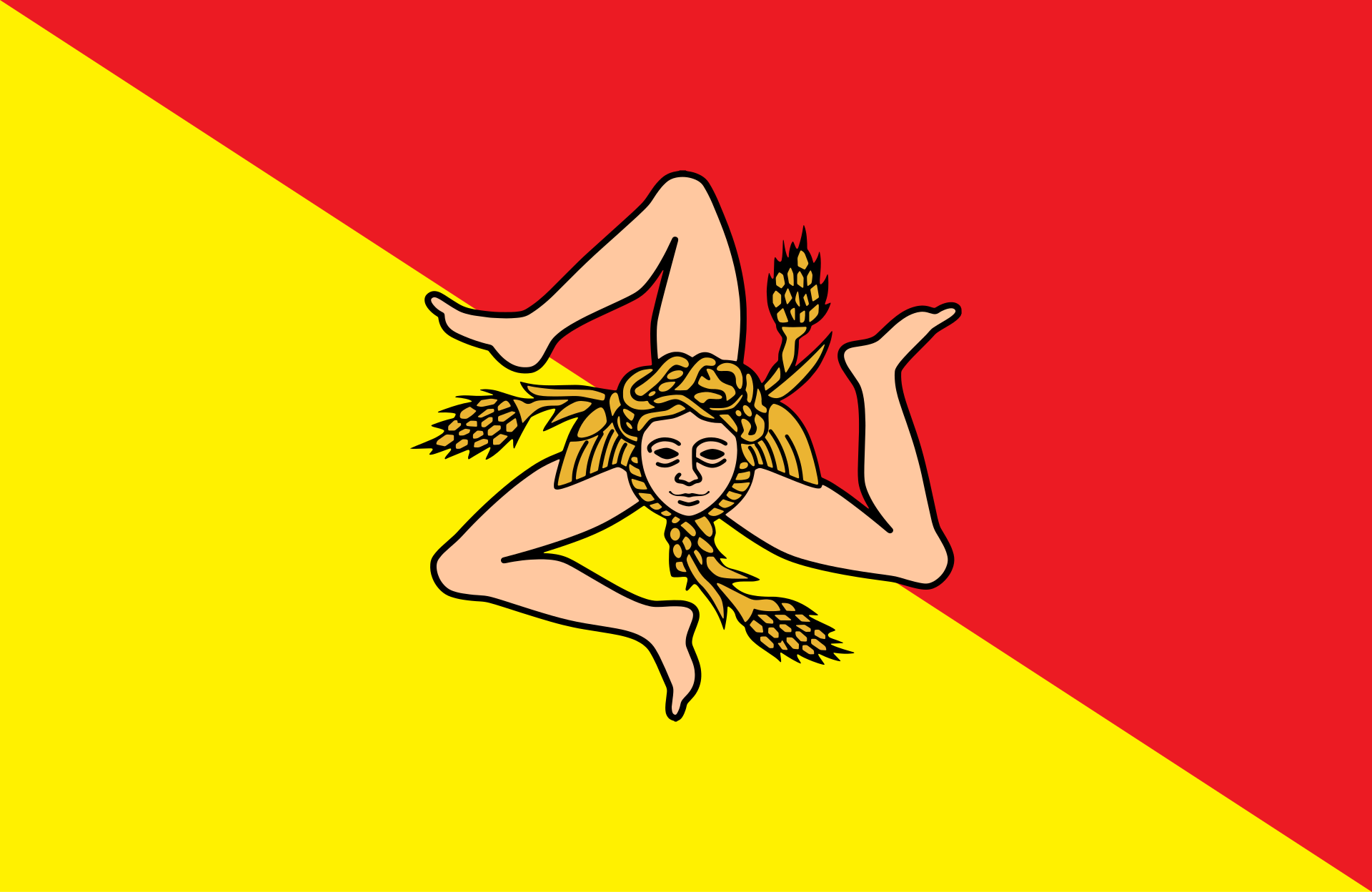

Sicilia

Sicilia

Basilicata

Basilicata

Calabria

Calabria

Puglia

Puglia

Geschichte

Geschichte

Islas Baleares

Islas Baleares

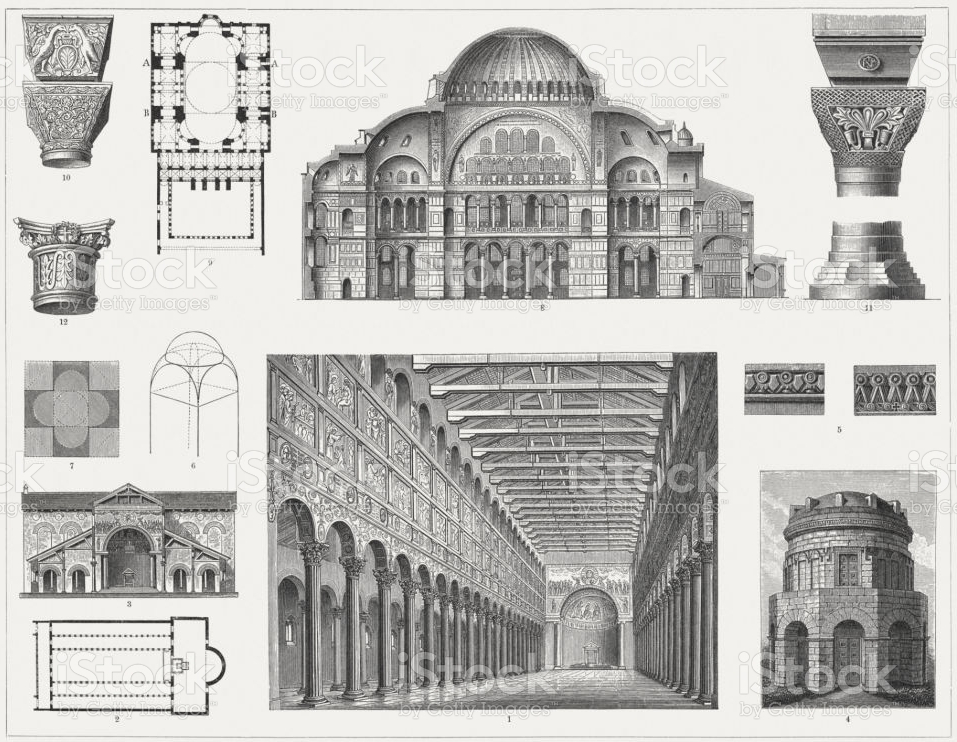

Architektur

Architektur

Zivilisation

Zivilisation