漢德百科全書 | 汉德百科全书

Architektur

Architektur

Chinesische Architektur

Chinesische Architektur

Beijing Shi-BJ

Beijing Shi-BJ

Geschichte

Geschichte

K 500 - 1000 nach Christus

K 500 - 1000 nach Christus

Urlaub und Reisen

Urlaub und Reisen

Rund 40 km südwestlich der Stadt liegen nur wenige Kilometer voneinander entfernt zwei eindrucksvolle buddhistische Tempelklöster. Sie sind am besten per Taxi zu erreichen - fast ein Tagesausflug, wenn man sich Zeit lässt.

Jietai Si: Das große Kloster liegt an einem Berghang mit Fernsicht. Namengebend ist die imposante dreistufige Ordinationsterrasse (jietai) in einer Halle rechts der Hauptachse. Mit ihrem Figurenschmuck stellt sie den Weltenberg Sumeru dar. Ehrwürdig sind bis zu 800 Jahre alte Grabpagoden und bis zu 1000 Jahre alte, skurrile Bäume. Tgl. 8-18 Uhr | Eintritt 30 Yuan

Tanzhe Si: Das inmitten bewaldeter Berge idyllisch gelegene Tempelkloster wurde um das Jahr 300 gegründet. Die meisten heutigen Bauten stammen aus dem 15.-18. Jh. Mächtige alte Bäume, darunter ein tausendjähriger Ginkgo, spenden Schatten. Tgl. 8.30-18 Uhr | Eintritt 30 Yuan

(Quelle:http://www.marcopolo.de/asien/china/peking/AusfluegeTouren_4.html)

Kongōbu-ji (金剛峯寺) ist der kirchliche Haupttempel des Kōyasan-Shingon-Buddhismus auf dem Berg Kōya (高野山, Kōya-san) in der Präfektur Wakayama, Japan. Sein Name bedeutet Tempel des Diamantberggipfels. Er ist Teil des UNESCO-Weltkulturerbes „Heilige Stätten und Pilgerrouten im Kii-Gebirge“.

Der Tempel wurde 1593 von Toyotomi Hideyoshi nach dem Tod seiner Mutter als Seigan-ji-Tempel erbaut, 1861 wiederaufgebaut und erhielt 1869 seinen heutigen Namen. Er beherbergt zahlreiche Schiebetüren, die von Kanō Tanyū (1602-1674) und Mitgliedern der Kyotoer Kanō-Schule gemalt wurden.

Der moderne Banryūtei (蟠龍庭-Felsengarten) des Tempels ist der größte Japans (2340 Quadratmeter) und besteht aus 140 Granitsteinen, die so angeordnet sind, dass sie ein Drachenpaar darstellen, das aus den Wolken aufsteigt, um den Tempel zu schützen.

Der 414. Abt des Kongōbu-ji ist Hochwürden Kogi Kasai, der auch als Erzbischof der Kōyasan-Shingon-Schule fungiert.

Im Tempel können Besucher den Predigten der Mönche zuhören und an Ajikan-Meditationssitzungen teilnehmen. Der Begriff ajikan bezieht sich auf eine grundlegende Atem- und Meditationsmethode des Shingon-Buddhismus: „Meditieren auf den Buchstaben A“, der im Siddhaṃ-Alphabet geschrieben wird.

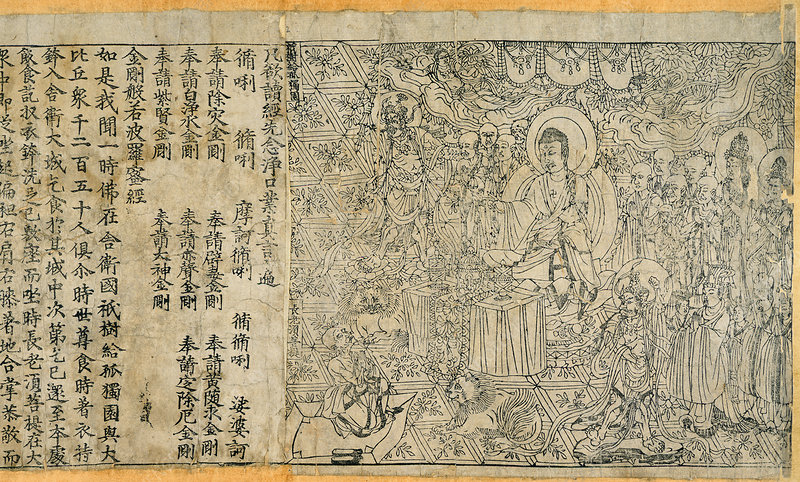

A page from the Diamond Sutra, printed in the 9th year of Xiantong Era of the Tang Dynasty, i.e. 868 CE. Currently located in the British Library, London.

According to the British Library, it is “the earliest complete survival of a dated printed book”.

Chinese: Jingang Borepoluomiduo Jing 金剛般若波羅蜜多經; shortened to Jingang Jing 金剛經

Japanese: 金剛般若波羅蜜多経, Kongō hannya haramita kyō, shortened to Kongō-kyō 金剛経

Korean: 금강반야바라밀경, geumgang banyabaramil gyeong, shortened to geumgang gyeong 금강경

Mongolian: Yeke kölgen sudur[6]

Vietnamese Kim cương bát-nhã-ba-la-mật-đa kinh, shortened to Kim cương kinh

Tibetan འཕགས་པ་ཤེས་རབ་ཀྱི་ཕ་རོལ་ཏུ་ཕྱིན་པ་རྡོ་རྗེ་གཅོད་པ་ཞེས་བྱ་བ་ཐེག་པ་ཆེན་པོའི་མདོ།, Wylie: ’phags pa shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa rdo rje gcod pa zhes bya ba theg pa chen po’i mdo

*Changjiang|Yangtze Fluß

*Changjiang|Yangtze Fluß

Beijing Shi-BJ

Beijing Shi-BJ

China

China

Geschichte

Geschichte

K 500 - 1000 nach Christus

K 500 - 1000 nach Christus

Hebei Sheng-HE

Hebei Sheng-HE

Jiangsu Sheng-JS

Jiangsu Sheng-JS

Kaiserkanal

Kaiserkanal

Shandong Sheng-SD

Shandong Sheng-SD

Tianjin Shi-TJ

Tianjin Shi-TJ

Urlaub und Reisen

Urlaub und Reisen

Weltkulturerbe

Weltkulturerbe

Wissenschaft und Technik

Wissenschaft und Technik

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

Zhejiang Sheng-ZJ

Hangzhou

Hangzhou

Der Kaiserkanal im Osten von China verläuft von der Stadt Hangzhou bis in die Hauptstadt des Landes, Peking. Die Stadt Hangzhou liegt in der Nähe von Shanghai und der Mündung des Changjiang-Flusses (im Westen oft auch Yangtsekiang-Fluss genannt), über Jahrtausende einer der fruchtbarsten Regionen Chinas. Die chinesischen Kaiser ließen den Großen Kanal anlegen, um Tributzahlungen und Naturalien-Steuern aus dem Süden des Landes in die Hauptstadt zu transportieren.

Auf chinesische heißt der Kaiserkanal 京杭大运河 Jing-Hang Da Zunhe, was übersetzt "Großer Beijing-Hangzhou Kanal" heißt. Im Westen wird der künstliche Fluss dagegen meist als Großer Kanal oder auch Kaiserkanal bezeichnet. Mit über 1800 Kilometern Gesamtlänge ist der Kaiserkanal die größte von Menschen geschaffene Wasserstraße der Welt. Der im Verlauf von vielen Jahrhunderten immer wieder ausgebaute Große Kanal ist teilweise bis zu 40 Metern breit und bis zu 9 Metern tief.(Quelle: http://www.forumchina.de/kaiserkanal)

Der Kaiserkanal (chinesisch 京杭大运河, Pinyin Jīng Háng Dà Yùnhé, d. h. Peking-Hangzhou Großer Kanal) ist die längste von Menschen geschaffene Wasserstraße der Welt. Mit einer Länge von mehr als 1800 Kilometern und einer Breite von bis zu 40 Metern verband er den Norden Chinas (Peking) mit dem fruchtbaren Mündungsgebiet des Jangtsekiang (Hangzhou). Er überwand einen Höhenunterschied von 42 Metern, war 3 bis 9 Meter tief und gilt als das Meisterwerk der Wasserbaukunst im alten China. Seit 2014 gehört er daher zum Welterbe der Menschheit.

大运河南起余杭(今杭州),北到涿郡(今北京),途经今浙江、江苏、山东、河北四省及天津、北京两市,贯通海河、黄河、淮河、长江、钱塘江五大水系,全长约1797公里。运河对中国南北地区之间的经济、文化发展与交流,特别是对沿线地区工农业经济的发展起了巨大作用。

京杭大運河(けいこうだいうんが)は、中国の北京から杭州までを結ぶ、総延長2500キロメートルに及ぶ大運河である。途中で、黄河と揚子江を横断している。戦国時代より部分的には開削されてきたが、隋の文帝と煬帝がこれを整備した。完成は610年。運河建設は人民に負担を強いて隋末の反乱の原因となったが、運河によって経済の中心地江南と政治の中心地華北、さらに元のクビライ・ハーンによって軍事上の要地である涿郡だった大都(後の北京)が結合して、中国統一の基盤が整備された。この運河は、その後の歴代王朝でもおおいに活用され、現在も中国の大動脈として利用されている。2014年の第38回世界遺産委員会でシルクロードなどとともに世界遺産リストに登録された。

The Grand Canal, known to the Chinese as the Beijing–Hangzhou Grand Canal (Jīng-Háng Dà Yùnhé), a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is the longest as well as the oldest canal or artificial river in the world and a famous tourist destination.[1] Starting at Beijing, it passes through Tianjin and the provinces of Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu and Zhejiang to the city of Hangzhou, linking the Yellow River and Yangtze River. The oldest parts of the canal date back to the 5th century BC, but the various sections were first connected during the Sui dynasty (581–618 AD). Dynasties in 1271-1633 significantly rebuilt the canal and altered its route to supply their capital Beijing.

The total length of the Grand Canal is 1,776 km (1,104 mi). Its greatest height is reached in the mountains of Shandong, at a summit of 42 m (138 ft).[2] Ships in Chinese canals did not have trouble reaching higher elevations after the pound lock was invented in the 10th century, during the Song dynasty (960–1279), by the government official and engineer Qiao Weiyue.[3] The canal has been admired by many throughout history including Japanese monk Ennin (794–864), Persian historian Rashid al-Din (1247–1318), Korean official Choe Bu (1454–1504), and Italian missionary Matteo Ricci (1552–1610).[4][5]

Historically, periodic flooding of the Yellow River threatened the safety and functioning of the canal. During wartime the high dikes of the Yellow River were sometimes deliberately broken in order to flood advancing enemy troops. This caused disaster and prolonged economic hardships. Despite temporary periods of desolation and disuse, the Grand Canal furthered an indigenous and growing economic market in China's urban centers since the Sui period. It has allowed faster trading and has improved China's economy. The southern portion remains in heavy use to the present day.

Le Grand Canal (chinois simplifié : 大运河 ; chinois traditionnel : 大運河 ; pinyin : ) de Chine, également connu sous le nom de Grand Canal Pékin-Hangzhou (chinois simplifié : 京杭大运河 ; chinois traditionnel : 京杭大運河 ; pinyin : ) est le plus grand canal ancien ou rivière artificielle du monde (1 794 km). Les parties les plus anciennes remontent au Ve siècle av. J.-C.. Il est inscrit au patrimoine mondial de l'UNESCO depuis 20141.

Il Gran Canale della Cina, conosciuto anche come Gran Canale Jing-Hang e Canale Imperiale, è il canale o fiume artificiale più lungo del mondo e collega Pechino, passando per Tianjin e le provincie di Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu e arrivando a Hangzhou nello Zhejiang e collega il fiume giallo e il fiume azzurro in Cina[1].

El Gran Canal de China (chino tradicional: 大運河, chino simplificado: 大运河, pinyin: Dà Yùnhé), conocido también como Gran Canal Pekín-Hangzhou (chino tradicional: 京杭大運河, chino simplificado: 京杭大运河, pinyin: Jīng Háng Dà Yùnhé) es el canal o río artificial más largo del mundo.1

En junio de 2014, la Unesco eligió el Gran Canal de China como Patrimonio de la Humanidad.2

En el año 604, el emperador Yang Guang de la dinastía Sui dejó la capital, Chang'an (en Xian) para trasladarse a Luoyang. En 605, el emperador ordenó la construcción de dos proyectos: transferir la capital del país a Luoyang (en Henan) y excavar el Gran Canal entre Pekín y Hangzhou.

En su origen se trataba de una serie de vías hidráulicas en la provincia Cheklang, al norte de China, que convergían con la ciudad de Pekín y Tianjin, atravesando las provincias de Hebeng, Shandong, Jiangsu y Zhejiang.

La construcción comenzó durante la dinastía Sui (581-618) y llegó a cubrir poco más de 1.700 kilómetros. Su nombre original era Da Yunhe, y en su tiempo constituyó el canal de agua más largo del mundo hecho por el hombre. Su misión era satisfacer las necesidades de las ciudades importantes con el agua de los ríos Yangste y Hual; permaneció en activo hasta el siglo XIX y después sufrió una serie de modificaciones, que en muchos casos culminaron en desastrosas inundaciones, y varias secciones se deterioraron hasta quedar separadas del cuerpo principal del canal.

Actualmente está dividido en siete subcanales, algunos de ellos muy contaminados, para el servicio exclusivo de aguas negras en desuso o con niveles insuficientes para la navegación. Pero los más grandes, como el canal Li y el Jiangnan son utilizados actualmente para el transporte de carbón y otros materiales; se estima que anualmente se mueven 100 millones de toneladas de carga.

Вели́кий кана́л[1] (кит. трад. 大運河, упр. 大运河, пиньинь: Dà Yùnhé — Даюньхэ[2]) — судоходный канал в Китае, одно из древнейших ныне действующих гидротехнических сооружений мира.

Строился в течение двух тысяч лет — с VI в. до н. э. до XIII в. н. э.[3] В настоящее время является одной из важнейших внутренних водных артерий КНР, соединяет крупные порты страны Шанхай и Тяньцзинь.

Протяжённость канала — 1782 км[4], а с ответвлениями в Пекин, Ханчжоу и Наньтун — 2470 км. Ширина в наиболее узкой части в провинциях Шаньдун и Хэбэй — 40 м, в самой широкой части в Шанхае — 350 м. Глубина фарватера — от 2 до 3 м. Канал оборудован 21 шлюзом. Максимальная грузопропускная способность составляет 10 млн тонн в год.

Канал соединяет реки Хуанхэ и Янцзы, включая в себя русла таких рек, как Байхэ, Вэйхэ, Сышуй и других, а также несколько озёр.

Великий канал состоит из нескольких сооружённых в разное время участков. Самый южный участок проложен в VII веке, самый северный — в XIII веке, а часть центрального участка от Хуайинь до Цзянду проходит по древнему каналу Ханьгоу.

Астронавт Уильям Поуг, будучи на борту Скайлэба, первоначально подумал, что увидел Великую Китайскую стену, но оказалось, что он видел Великий канал Китая[5].

Architektur

Architektur

Chinesische Architektur

Chinesische Architektur

Beijing Shi-BJ

Beijing Shi-BJ

Chinesische Mauer

Chinesische Mauer

Geschichte

Geschichte

I 500 - 0 vor Christus

I 500 - 0 vor Christus

Geschichte

Geschichte

K 500 - 1000 nach Christus

K 500 - 1000 nach Christus

Der in seiner heutigen Form aus der Ming-Zeit (Mingchao, 明朝, 1368-1644) stammende Juyongguan-Pass stellt einen der wichtigsten Übergänge der Großen Mauer dar. Die Lage in dem von steilen Bergen umgebenen Tal war in militärstrategischer Hinsicht von großen Vorteil. Außerdem war Juyongguan lange Zeit für seine natürliche Schönheit bekannt und zählte zu den Acht Ansichten Yanjings. Heutzutage sind die umliegende Berge allerdings ziemlich kahl und weisen nur einen geringen Pflanzenbewuchs auf. Gleichwohl ist der Blick in das Tal und auf die Berge nach wie vor sehr eindrucksvoll. Besucher sollten sich dafür allerdings auf einen sehr anstrengenden und steilen Aufstieg gefasst machen.

Juyongguan oder Juyong-Pass (chinesisch 居庸關 / 居庸关, Pinyin Jūyōng Guān) liegt im 18 km langen Guangou-Tal, das im Pekinger Stadtbezirk Changping liegt, mehr als 50 km von der Stadt entfernt. Er ist einer der drei größten Übergänge der Chinesischen Mauer. Die beiden anderen sind Jiayuguan und Shanhaiguan.

居庸关是明长城其中一座出名的关城,与附近的八达岭长城同为首都北京西北方的重要屏障。与倒马关和紫荆关合称“内三关”。居庸关也是太行八陉中军都陉的重要关隘,始建于秦代。居庸关位于北京西北部,距北京约60公里。居庸关设于太行山馀脉之军都山峡谷之间的关沟,两侧均有高山耸立,纵深约20公里,地势险要。

Architektur

Architektur

*Architekten

*Architekten

Architektur

Architektur

Byzantinische Architektur

Byzantinische Architektur

Architektur

Architektur

Römische Architektur

Römische Architektur

Geschichte

Geschichte

K 500 - 1000 nach Christus

K 500 - 1000 nach Christus

Geschichte

Geschichte

J 0 - 500 nach Christus

J 0 - 500 nach Christus

Geschichte

Geschichte

L 1000 - 1500 nach Christus

L 1000 - 1500 nach Christus

Geschichte

Geschichte

K 500 - 1000 nach Christus

K 500 - 1000 nach Christus

Die Stadt Konstantinopel wurde von dorischen Siedlern aus dem griechischen Mutterland um 660 v. Chr. unter dem Namen Byzantion gegründet. Am 11. Mai 330 n. Chr. machte sie der römische Kaiser Konstantin der Große zu seiner Hauptresidenz, baute sie großzügig aus und benannte sie offiziell in Nova Roma (Νέα Ῥώμη Nea Rhōmē, „Neues Rom“) um. In der Spätantike beanspruchte die Stadt auch den Rang als „Zweites Rom“. Nach dem Tod Kaiser Konstantins 337 wurde die Stadt offiziell in Constantinopolis umbenannt. Sie war die Hauptstadt des Oströmischen Reichs und blieb dies – abgesehen von der Eroberung im Vierten Kreuzzug – ununterbrochen bis zur Eroberung durch die Osmanen 1453. Unter den Namen Kostantiniyye / قسطنطينيه und استانبول / Istānbūl war es dann bis 1923 die Hauptstadt des Osmanischen Reichs.[1]

Spätestens ab 1930 setzte sich der Name Istanbul, der bereits im Seldschukischen und Osmanischen Reich gebräuchlich war,[2] auch international durch. Als Prototyp einer imperialen Stadt ist es seit dem 4. Jahrhundert eine Weltstadt.

君士坦丁堡(古希腊语:Κωνσταντινούπολις/Κωνσταντινούπολη;拉丁语:Constantinopolis;奥斯曼土耳其语:قسطنطینیه;现代土耳其语:İstanbul)又译康斯坦丁堡,是土耳其最大城市伊斯坦布尔的旧名,现在则指伊斯坦布尔金角湾与马尔马拉海之间的地区。它曾经是罗马帝国、拜占庭帝国、拉丁帝国和奥斯曼帝国的首都。

公元330年,罗马皇帝君士坦丁一世在拜占庭建立新都,命名为新罗马(拉丁语:Nova Roma;希腊语:Νέα Ρώμη),但该城普遍被以建立者之名称作君士坦丁堡。在公元12世纪时[1],君士坦丁堡是全欧洲规模最大且最为繁华的城市[2]。

后来拜占庭帝国逐渐衰落,领土范围也缩减到君士坦丁堡及其周边地区。公元1453年,君士坦丁堡被奥斯曼帝国攻陷,此后成为奥斯曼帝国的新首都,再次繁荣起来。西方学者们习惯上将基督教治下(330年至1453年)的该城称作君士坦丁堡,而将此后伊斯兰教治下的城市称作伊斯坦布尔。如今,君士坦丁堡之名仍然被东正教沿用,教众们将君士坦丁堡教会的领袖,亦是整个东正教会名义上地位最高的领袖称作君士坦丁堡普世牧首。

君士坦丁堡亦以其宏伟的建筑而闻名。著名的建筑包括圣索菲亚大教堂、君士坦丁堡大皇宫、君士坦丁堡竞技场和黄金城门,大道与广场在其间星罗棋布。在1204年和1453年两次被劫掠之前,君士坦丁堡还保存着为数众多的艺术和文学作品[3]。在被奥斯曼帝国攻克之时,该城已经逐渐破败,但在此后得到了迅速的复兴与发展,并于17世纪中叶再次成为当时世界第一大城市[1]。

コンスタンティノープル(英: Constantinople、ラテン語: Constantinopolis、古代ギリシア語: Κωνσταντινούπολις)は、東ローマ帝国の首都であった都市で、現在のトルコの都市イスタンブールの前身である。

強固な城壁の守りで知られ、330年の建設以来、1453年の陥落まで難攻不落を誇り、東西交易路の要衝として繁栄した。正教会の中心地ともなり、現在もコンスタンティノープル総主教庁が置かれている。

コンスタンティノープルは、330年にローマ皇帝コンスタンティヌス1世が、古代ギリシアの植民都市ビュザンティオン (古希: Βυζάντιον) の地に建設した都市である。この地は古来よりアジアとヨーロッパを結ぶ東西交易ルートの要衝であり、また天然の良港である金角湾を擁していた。都市名は「コンスタンティヌスの町」を意味する。

330年より東ローマ帝国の行政首都として建設された[1]。西ローマ帝国において西方正帝が消失した後には同地で「新ローマ」「第2のローマ」とする意識が育ち、遅くとも6世紀中頃までには定着した。東ローマ帝国の隆盛と共に、30万~40万の人口を誇るキリスト教圏最大の都市として繁栄し、「都市の女王」「世界の富の3分の2が集まる所」とも呼ばれた。また古代の建造物が残る大都市としてその偉容を誇った。正教会の首長であるコンスタンティノープル総主教庁が置かれ、正教会の中心ともなり、ビザンティン文化の中心でもあった。都市の守護聖人は聖母マリアである。

コンスタンティノープルは強固な城壁の守りでも知られ、東ローマ帝国の長い歴史を通じて外敵からの攻撃をたびたび跳ね返した。しかし1204年に第4回十字軍の攻撃を受けると衰退が加速した。1453年にオスマン帝国によりコンスタンティノープルが陥落し、東ローマ帝国が滅亡すると、この街はオスマン帝国の首都となった。日本ではこれ以後をトルコ語によるイスタンブールの名で呼ぶことが多い。ただし、公式にイスタンブールと改称されるのはトルコ革命後の1930年である。

Constantinople (Greek: Κωνσταντινούπολις, translit. Kōnstantinoúpolis; Latin: Cōnstantīnopolis) was the capital city of the Roman Empire (330–395), of the Byzantine Empire (395–1204 and 1261–1453), and also of the brief Crusader state known as the Latin Empire (1204–1261), until finally falling to the Ottoman Empire (1453–1923). It was reinaugurated in 324 from ancient Byzantium as the new capital of the Roman Empire by Emperor Constantine the Great, after whom it was named, and dedicated on 11 May 330.[5] The city was located in what is now the European side and the core of modern Istanbul.

From the mid-5th century to the early 13th century, Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest city in Europe.[6] The city was also famed for its architectural masterpieces, such as the Greek Orthodox cathedral of Hagia Sophia, which served as the seat of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, the sacred Imperial Palace where the Emperors lived, the Galata Tower, the Hippodrome, the Golden Gate of the Land Walls, and the opulent aristocratic palaces lining the arcaded avenues and squares. The University of Constantinople was founded in the fifth century and contained numerous artistic and literary treasures before it was sacked in 1204 and 1453,[7] including its vast Imperial Library which contained the remnants of the Library of Alexandria and had over 100,000 volumes of ancient texts.[8] It was instrumental in the advancement of Christianity during Roman and Byzantine times as the home of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople and as the guardian of Christendom's holiest relics such as the Crown of Thorns and the True Cross.

Constantinople was famed for its massive and complex defences. The first wall of the city was erected by Constantine I, and surrounded the city on both land and sea fronts. Later, in the 5th century, the Praetorian Prefect Anthemius under the child emperor Theodosius II undertook the construction of the Theodosian Walls, which consisted of a double wall lying about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) to the west of the first wall and a moat with palisades in front.[9] This formidable complex of defences was one of the most sophisticated of Antiquity. The city was built intentionally to rival Rome, and it was claimed that several elevations within its walls matched the 'seven hills' of Rome. Because it was located between the Golden Horn and the Sea of Marmara the land area that needed defensive walls was reduced, and this helped it to present an impregnable fortress enclosing magnificent palaces, domes, and towers, the result of the prosperity it achieved from being the gateway between two continents (Europe and Asia) and two seas (the Mediterranean and the Black Sea). Although besieged on numerous occasions by various armies, the defences of Constantinople proved impregnable for nearly nine hundred years.

In 1204, however, the armies of the Fourth Crusade took and devastated the city, and its inhabitants lived several decades under Latin misrule. In 1261 the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos liberated the city, and after the restoration under the Palaiologos dynasty, enjoyed a partial recovery. With the advent of the Ottoman Empire in 1299, the Byzantine Empire began to lose territories and the city began to lose population. By the early 15th century, the Byzantine Empire was reduced to just Constantinople and its environs, along with Morea in Greece, making it an enclave inside the Ottoman Empire; after a 53-day siege the city eventually fell to the Ottomans, led by Sultan Mehmed II, on 29 May 1453,[10] whereafter it replaced Edirne (Adrianople) as the new capital of the Ottoman Empire.[11]

Constantinople (en latin Constantinopolis, en grec ancien Κωνσταντινούπολις (Kônstantinoúpolis), en grec moderne Κωνσταντινούπολη (Konstantinoúpoli), en turc ottoman قسطنطینیه (Kostantiniyye), en arménien Կոստանդնուպոլիս (Kostandnoupolis) est l'appellation ancienne et historique de l'actuelle ville d'Istanbul en Turquie (du 11 mai 330 au 28 mars 1930). Son nom originel, « Byzance » (en grec ancien Βυζάντιον (Byzántion), venant soit du mot grec buzō signifiant « resserré » en référence au Bosphore, soit du mot thrace βυζή buzē : « rivage »), n'était plus en usage à l'époque de l'Empire, mais a été repris depuis le XVIe siècle par les historiens modernes.

Les habitants de Byzance sont les « Byzantins » et ceux de Constantinople les « Constantinopolitains »N 1. Depuis le XVIe siècle, les historiens modernes ont élargi la signification de « Byzantins » à tous les citoyens de l'Empire romain d'Orient, lui-même qualifié de « byzantin ». « Constantinople » est la francisation de Konstantinoupolis, qui, en grec, signifie « ville de Constantin ». Ce nom lui a été donné par l'empereur romain Constantin Ier lui-même, qui choisit d'en faire la capitale de l'empire à partir du 11 mai 330 et qui la proclama la « Deuxième Rome »1,N 2.

Costantinopoli (in latino: Constantinopolis; in greco: Κωνσταντινούπολις, Konstantinoupolis), o Nuova Roma (in latino Nova Roma, in greco Νέα Ῥώμη, Nea Rōmē), o la Città d'Oro, sono alcuni dei nomi e degli epiteti dell'odierna città di Istanbul, sulle rive del Bosforo, maggior centro urbano della Turchia. Il nome Costantinopoli fu in particolare tenuto dalla città nel periodo intercorrente tra la rifondazione ad opera dell'imperatore romano Costantino I e la conquista da parte del sultano ottomano Maometto II.

Durante tale periodo la città fu una delle capitali dell'Impero romano (anni 330-395) e capitale dell'Impero romano d'Oriente (anni 395-1204 e 1261-1453) e dell'Impero latino (anni 1204-1261). Il nome rimase comunque in uso anche durante l'Impero ottomano, quando era nota ufficialmente come Kostantîniyye (قسطنطينيه) in lingua turca ottomana e come Costantinopoli presso gli occidentali, sino al 1930, quando il nome Istanbul in lingua turca venne ufficializzato e reso esclusivo dalle autorità turche.

È inoltre la città che subì più assedi nella storia umana, capitolando solamente due volte: la prima durante il saccheggio dei crociati nel 1204 e la seconda quando fu definitivamente conquistata dagli ottomani nel 1453.

Constantinopla (en griego antiguo: Κωνσταντινούπολις, Kōnstantinoúpolis, abreviado como en griego medieval ἡ Πόλις, ί Pόlis, 'La Ciudad'; en latín Cōnstantinōpolis, en turco otomano formal Konstantiniyye) es el nombre histórico de la actual ciudad de Estambul (en idioma turco İstanbul), situada a ambos lados del Estrecho del Bósforo en Turquía, y que fue capital de distintos imperios a lo largo de la historia: del Imperio romano (330-395), del Imperio romano de Oriente o Imperio bizantino (395-1204 y 1261-1453), del Imperio latino (1204-1261) y del Imperio otomano (1453-1922), que empezó con la Caída de Constantinopla y terminó con la Ocupación de Constantinopla.

Estratégicamente situada entre el Cuerno de Oro y el mar de Mármara en el punto de encuentro de Europa y Asia, la Constantinopla bizantina fue baluarte de la Cristiandad y heredera del mundo griego y romano.[cita requerida] A lo largo de la Edad Media fue la mayor y más rica ciudad de Europa[cita requerida], y conocida como «la Reina de las Ciudades» (Basileuousa Polis). Por otra parte, fue llamada la Encrucijada del Mundo, pues era el nexo de comercio entre Asia, Europa y África (marítimo).

Dependiendo de sus gobernantes y el momento histórico, ha tenido diferentes nombres; entre los más comunes están Bizancio (en griego Byzantion), Stamboul o Nueva Roma (en griego Νέα Ῥώμη, en latín Nova Roma), este último un nombre más eclesiástico que oficial. Fue conocida por la Guardia Varega con el nombre de Miklagarðr (Gran Ciudad). Fue rebautizada oficialmente Estambul (su nombre actual) en 1930 mediante la Ley Turca de Servicio Postal, una de las reformas nacionales impulsadas por Atatürk.

Jun yao (chinesisch 钧窑, Pinyin Jun yao, W.-G. Chün yao, englisch Jun Kiln ‚Jun-Brennofen‘) ist die Fachbezeichnung für in der Stadt Yuzhou der chinesischen Provinz Henan befindliche song-zeitliche Porzellanbrennöfen. Der Jun-Brennofen zählt zu den Fünf berühmte Brennöfen der Song-Dynastie, er wird auch Jun yao 均窑 oder Junzhou yao 钧州窑 genannt.[1] Die Stätte wurde 1951 entdeckt. Das Jun-Porzellan hat einen dunklen Grundton mit einer blauschwarz gesprenkelten Glasur, die meist mit einem feinen Netz von Rissen überzogen ist.

钧窑也称均窑,均州窑是宋代初年,在今河南省禹州市神垕镇钧台建立的瓷窑。钧窑古瓷窑址现在是全国重点文物保护单位,原址处建有“禹州钧官窑址博物馆”[1]。

钧窑是中国宋代五大名窑之一,创烧于唐,兴盛于宋,复烧于金元,延至明清仍继续仿制,历经千年而不衰,形成了一个庞大的钧窑系,与汝、官、哥、定诸窑齐名。迄今为止,在禹州境内已发现北宋钧窑遗址多达四十处,尤以神垕镇大刘山下最为集中。

禹州现存最早的《钧州志》中说:“瓷窑在州西大刘山下”。在禹州市神垕镇下白峪村和苌庄乡等地,先后出土黑、褐釉高温窑变花瓷,被陶瓷学家称为“唐钧”,它是宋代钧瓷的先声。宋“靖康之变”(1126年)后,宋室南迁,官钧窑停烧,钧瓷一时受挫。到金、元时代,钧瓷有了新的发展,各地争相仿制,风靡一时,钧窑播火全国。元末明初,因战乱和灾荒,钧窑生产渐衰。明、清时期,制瓷中心南移,北方诸名窑衰退,钧窑也基本停烧。清朝晚期,钧瓷复苏。到光绪三十年(1904年),神垕镇烧制钧瓷者已有十余家。民国年间,因战乱、灾荒频繁,钧瓷生产举步维艰。至民国三十一年(1942年)后,因大旱和政局混乱,艺人外流,钧瓷生产趋于停产状态。1949年以后,特别是中国改革开放以来得到了快速发展,被做为国礼,达到了一个新的高度。

钧窑土脉细,釉彩有兔丝纹:红的像胭脂、朱沙,青翠的像葱,紫色如紫玫瑰等多种颜色,俗称海棠红、梅子青、茄皮紫、天兰等色彩。钧窑瓷器常发生窑变,除本色釉外还会变出其他颜色,而钧瓷的名贵正在于其独特的窑变釉色,其釉色是烧制过程中自然形成,非人工描绘,每一件钧瓷的釉色都是唯一的,故有“钧瓷无双”的说法,钧瓷的釉质深厚透活,晶莹玉润,有明快的流动感。

明代文震亨在《长物志》一书中对钧窑的评论:“均州窑色如胭脂者为上,青若葱翠、紫若黑色者次之,杂色者不贵。”[2] 景德镇窑在清代也烧制仿钧窑瓷器。[3]

Jun ware (Chinese: 鈞窯; pinyin: Jūn yáo; Wade–Giles: Chün-yao) is a type of Chinese pottery, one of the Five Great Kilns of Song dynasty ceramics. Despite its fame, much about Jun ware remains unclear, and the subject of arguments among experts. Several different types of pottery are covered by the term, produced over several centuries and in several places, during the Northern Song dynasty (960–1126), Jin dynasty (1115–1234) and Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), and (as has become clearer in recent years) lasting into the early Ming dynasty.[1]

Some of the wares were popular, especially the drinking vessels, but others seem to have been made for the imperial court and are known as "official Jun wares"; they are not mentioned in contemporary documents and their dating remains somewhat controversial. These are mostly bowls for growing bulbs or flower-pots with matching stands, such as can be seen in many paintings of scenes in imperial palaces.[2] The consensus that seems to be emerging, driven largely by the interpretation of excavations at kiln sites, divides Jun wares into two groups: a large group of relatively popular wares made in simple shapes from the Northern Song to (at lower quality) the Yuan, and a much rarer group of official Jun wares made at a single site (Juntai) for the imperial palaces in the Yuan and early Ming periods.[3] Both types rely largely for their effect on their use of the blue and purple glaze colours; the latter group are sturdy shapes for relatively low-status uses such as flowerpots and perhaps spitoons.[4]

The most striking and distinctive Jun wares use blue to purple glaze colours, sometimes suffused with white, made with straw ash in the glaze.[5] They often show "splashes" of purple on blue, sometimes appearing as though random, though they are usually planned. A different group are "streaked" purple on blue,[6] the Chinese describing the streaks as "worm-tracks". This is a high-prestige stoneware which was greatly admired and often imitated in later periods. But colours range from a light greenish-brown through green to blue and purple. The shapes are mostly simple, except for the official wares, and other decoration is normally limited to the glaze effects.[7] Most often, the "unofficial" wares are wheel-thrown, but the official ones moulded.

The wares are stoneware in terms of Western classification, and "high-fired" or porcelain in Chinese terms (where the class of stoneware is not generally recognised). Like the still more prestigious Ru ware, they are often not quite fired as high as the normal stoneware temperature range, and the body remains permeable to water.[8] They form a "close relative" of the wider group of Northern celadons or greenwares.[9]

Religion

Religion

Unternehmen

Unternehmen

Geographie

Geographie

Kunst

Kunst

Traditionen

Traditionen