漢德百科全書 | 汉德百科全书

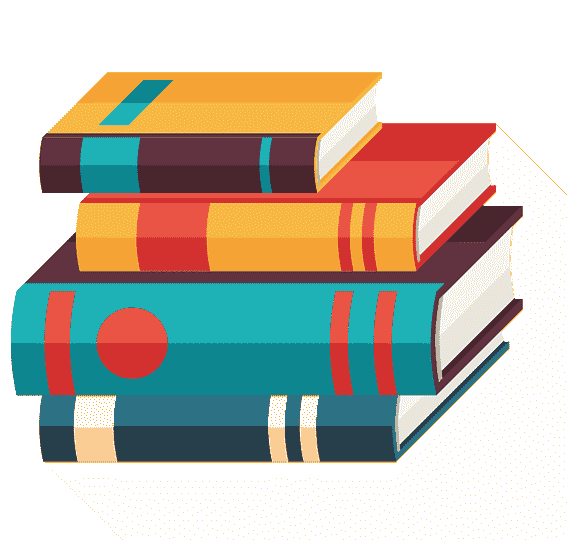

Die Druckerpresse wurde um 1440 von dem Deutschen Johannes Gutenberg im Römischen Reich erfunden. Gutenbergs Presse war eine handgekurbelte Presse, die Tinte über die erhabenen Flächen beweglicher Metalltypen rollte und gegen ein Blatt Papier drückte. Vor der Einführung des Buchdrucks mussten alle Texte von Hand geschrieben oder durch typografischen Handdruck erstellt werden, wobei etwa 40 bis 50 Seiten pro Tag produziert werden konnten. Die früheste Druckerpresse konnte 3.600 Seiten pro Tag produzieren, wodurch sich die Menge an gedrucktem Text, die der Welt zur Verfügung stand, dramatisch erhöhte. Bis zum Jahr 1500 hatten die Druckerpressen mehr als 20 Millionen Bände an Text produziert. Der Buchdruck öffnete die Tür für die Massenproduktion von Büchern und führte zu einem weit verbreiteten Austausch von Wissen auf der ganzen Welt. Zum ersten Mal hatte der Durchschnittsbürger Zugang zu Büchern und dem Wissen, das sie mit sich brachten. Die Druckerpresse gilt als eine der wichtigsten Erfindungen in der Geschichte der Menschheit. Das erste große Buch, das mit der Presse gedruckt wurde, war die Gutenberg-Bibel, die 1454 fertiggestellt wurde.

印加帝国(克丘亚语:Tawantinsuyu)是11世纪至16世纪时位于南美洲的古老帝国,亦是前哥伦布时期美洲最大的帝国,[1]印加帝国的政治、军事和文化中心位于今日秘鲁的库斯科。印加帝国的重心区域分布在南美洲的安第斯山脉上,其主体民族印加人也是美洲三大文明印加文明的缔造者。

印加人的祖先生活在秘鲁的高原地区,后来他们迁徙到库斯科,建立了库斯科王国,这个国家在1438年发展为印加帝国。印加帝国在1438年到1533年间,运用了从武力征服,到和平同化等各种方法,使得印加帝国的版图几乎涵盖了整个南美洲西部(地跨秘鲁、厄瓜多尔、哥伦比亚、玻利维亚、智利、阿根廷),是一个幅员辽阔的南美洲印第安人帝国。

除了印加帝国的官方语言克丘亚语,印加人还使用数百种美洲原住民语言和各种的克丘亚语方言。印加人称印加帝国为Tawantinsuyu,意为“四方之地”,或是“四地之盟”。印加帝国内部存在着多种原始信仰,但是印加的统治阶级推崇印加宗教,信仰太阳神因蒂、创世神维拉科查、地球女神帕查玛玛等神明。[2]印加帝国的君主称萨帕·印卡,意为“独一无二的君主”,同时萨帕·印卡亦被印加人当作“太阳的儿子”。

印加帝国的国力在君主瓦伊纳·卡帕克统治期间达到顶峰。1526年,西班牙征服者弗朗西斯科·皮萨罗带领一支有168人的军队从巴拿马南下,发现了印加帝国。1529年,在瓦伊纳·卡帕克感染天花而意外去世后,两位继承人选瓦斯卡尔与阿塔瓦尔帕为了争夺王位,而爆发血腥内战,大大地削弱了印加帝国的实力。1533年,西班牙人施计杀掉了赢得内战的阿塔瓦尔帕,皮萨罗的军队与数十万名原住民盟军成功将印加征服,印加帝国灭亡,沦为西班牙帝国的殖民地。印加人的最后抵抗势力比尔卡班巴王国亦在1572年灭亡。

Als Inka (Plural Inka oder Inkas) wird heute eine indigene urbane Kultur in Südamerika bezeichnet. Oft werden als Inka auch nur die jeweiligen herrschenden Personen dieser Kultur bezeichnet. Sie herrschten zwischen dem 13. und 16. Jahrhundert über ein weit umspannendes Reich von über 200 ethnischen Gruppen,[1] das einen hohen Organisationsgrad aufwies. Zur Zeit der größten Ausdehnung um 1530 umfasste es ein Gebiet von rund 950.000 Quadratkilometern, sein Einfluss erstreckte sich vom heutigen Ecuador bis nach Chile und Argentinien; ein Gebiet, dessen Nord-Süd-Ausdehnung größer war als die Strecke vom Nordkap bis nach Sizilien. Entwicklungsgeschichtlich sind die Inka mit den bronzezeitlichen Kulturen Eurasiens vergleichbar. Das rituelle, administrative und kulturelle Zentrum war die Hauptstadt Qusqu (Cusco) im Hochgebirge des heutigen Peru.

Ursprünglich war mit dem Begriff „Inka“ die Bezeichnung eines Stammes gemeint, der nach eigener Auffassung dem Sonnengott Inti entstammte und die Umgebung Cuscos besiedelte. Seine herrschende Sippe fungierte später als Adel des gleichnamigen theokratischen Reiches. Aus ihr rekrutierten sich auch der Klerus[2] und die Offiziere der Inka-Armee. Sapa Inka („einziger Inka“) war der Titel des Inka-Herrschers des Tawantinsuyu („Land der vier Teile, Reich der vier Weltgegenden“ – so die Selbstbezeichnung des Reiches).

インカ帝国(インカていこく、スペイン語:Imperio Inca、ケチュア語:タワンティン・スウユ(Tawantinsuyo, Tahuantinsuyo))は、南アメリカのペルー、ボリビア(チチカカ湖周辺)、エクアドルを中心にケチュア族が築いた国。文字を持たない社会そして文明であった。

首都はクスコ。世界遺産である15世紀のインカ帝国の遺跡「マチュ・ピチュ」から、さらに千メートル程高い3,400mの標高にクスコがある。1983年12月9日、クスコの市街地は世界遺産となった。

前身となるクスコ王国は13世紀に成立し、1438年のパチャクテク即位による国家としての再編を経て、1533年にスペイン人のコンキスタドールに滅ぼされるまで約200年間続いた。最盛期には、80の民族と1,600万人の人口をかかえ、現在のチリ北部から中部、アルゼンチン北西部、コロンビア南部にまで広がっていたことが遺跡および遺留品から判明している。

インカ帝国は、アンデス文明の系統における最後の先住民国家である。メキシコ・グアテマラのアステカ文明、マヤ文明と対比する南米の原アメリカの文明として、インカ文明と呼ばれることもある。その場合は、巨大な石の建築と精密な石の加工などの技術、土器や織物などの遺物、生業、インカ道路網を含めたすぐれた統治システムなどの面を評価しての呼称である。なお、インカ帝国の版図に含まれる地域にはインカ帝国の成立以前にも文明は存在し、プレ・インカと呼ばれている。

インカ帝国は、被征服民族についてはインカ帝国を築いたケチュア族の方針により比較的自由に自治を認めていたため、一種の連邦国家のような体をなしていた。

The Inca Empire (Quechua: Tawantinsuyu, lit. "The Four Regions"[4]), also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire, was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America.[5] Its political and administrative structure is considered by most scholars to have been the most developed in the Americas before Columbus' arrival.[6] The administrative, political and military center of the empire was located in Cusco, Peru. The Inca civilization arose from the Peruvian highlands sometime in the early 13th century. Its last stronghold was conquered by the Spanish in 1572.

From 1438 to 1533, the Incas incorporated a large portion of western South America, centered on the Andean Mountains, using conquest and peaceful assimilation, among other methods. At its largest, the empire joined Peru, southwest Ecuador, western and south central Bolivia, northwest Argentina, northern Chile and a small part of southwest Colombia into a state comparable to the historical empires of Eurasia. Its official language was Quechua.[7] Many local forms of worship persisted in the empire, most of them concerning local sacred Huacas, but the Inca leadership encouraged the sun worship of Inti – their sun god – and imposed its sovereignty above other cults such as that of Pachamama.[8] The Incas considered their king, the Sapa Inca, to be the "son of the sun."[9]

The Inca Empire was unique in that it lacked many features associated with civilization in the Old World. In the words of one scholar,[10]

The Incas lacked the use of wheeled vehicles. They lacked animals to ride and draft animals that could pull wagons and plows... [They] lacked the knowledge of iron and steel... Above all, they lacked a system of writing... Despite these supposed handicaps, the Incas were still able to construct one of the greatest imperial states in human history.

— Gordon McEwan, The Incas: New Perspectives

Notable features of the Inca Empire include its monumental architecture, especially stonework, extensive road network reaching all corners of the empire, finely-woven textiles, use of knotted strings (quipu) for record keeping and communication, agricultural innovations in a difficult environment, and the organization and management fostered or imposed on its people and their labor.

The Incan economy has been described in contradictory ways by scholars:[11]

... feudal, slave, socialist (here one may choose between socialist paradise or socialist tyranny)

— Darrell E. La Lone, The Inca as a Nonmarket Economy: Supply on Command versus Supply and Demand

The Inca empire functioned largely without money and without markets. Instead, exchange of goods and services was based on reciprocity between individuals and among individuals, groups, and Inca rulers. "Taxes" consisted of a labour obligation of a person to the Empire. The Inca rulers (who theoretically owned all the means of production) reciprocated by granting access to land and goods and providing food and drink in celebratory feasts for their subjects.[12]

L’Empire inca (Tahuantinsuyu, Tahuantinsuyo ou Tawantin Suyu en quechua, signifiant « quatre en un » ou « le tout des quatre parts »1) fut, du XVe au XVIe siècle, le plus vaste empire de l'Amérique précolombienne. Son territoire s'est en effet étendu, à son extension maximale, sur près de 4 500 km de long, depuis le Sud-Ouest de l'actuelle Colombie (au Río Patía), au nord, jusqu'au milieu de l'actuel Chili (au Río Maule), au sud, et comprenant la quasi totalité des territoires actuels du Pérou et de l'Équateur, ainsi qu'une partie importante de la Bolivie et significative de l'Argentine du Nord-Ouest2.

L'Impero inca (Tawantinsuyu in lingua aymara e quechua moderne, o Tahuantinsuyo in antica lingua quechua) è stato il più vasto impero precolombiano del continente americano. La sua esistenza va dal XIII secolo fino al XVI secolo e la sua capitale fu Cuzco, nell'attuale Perù.

Il Perù è stato la culla della civiltà inca, uno dei maggiori popoli nativi americani. La civiltà Inca unificò, conquistando o annettendo pacificamente, la maggior parte dei territori occidentali dell'America del Sud. A ogni popolo conquistato venivano imposti l'idioma e la religione dell'impero. A loro volta, gli inca si arricchivano della cultura dei popoli annessi.

El Imperio incaico o inca (en quechua: Tawantinsuyu, lit. "Las cuatro regiones o divisiones") fue el mayor imperio en la América precolombina.2

Al territorio del mismo se denominó Tawantinsuyu y al período de su dominio se le conoce, además, como incanato y/o incario. Floreció en la región andina del subcontinente entre los siglos xv y xvi, como consecuencia del apogeo de la civilización incaica.[cita requerida] Abarcó cerca de dos millones de kilómetros cuadrados entre el océano Pacífico y la selva amazónica, desde las cercanías de Pasto (Colombia) en el norte hasta el río Maule (Chile) por el sur.

Los orígenes del imperio se remontan a la victoria de las etnias cuzqueñas (Región Sur del actual Perú), lideradas por Pachacútec, frente a la confederación de estados chancas en 1438. Luego de la victoria, el curacazgo incaico fue reorganizado por Pachacútec, con quien el Imperio incaico inició una etapa de continua expansión, que prosiguió con su hermano Cápac Yupanqui, luego por parte del décimo inca Túpac Yupanqui, y finalmente del undécimo inca Huayna Cápac, quien consolidó los territorios. En esta etapa la civilización incaica logró la máxima expansión de su cultura, tecnología y ciencia, desarrollando los conocimientos propios y los de la región andina, así como asimilando los de otros estados conquistados.

La Civilización incaica surgió de las tierras altas del Perú en algún momento a principios del siglo xiii. Su último bastión fue conquistado por los españoles en 1572.

Luego de este periodo de apogeo el imperio entró en declive por diversos problemas, siendo el principal la confrontación por el trono entre los hijos de Huayna Cápac: los hermanos Huáscar y Atahualpa, que derivó incluso en una guerra civil. Entre los incas la viruela acabó con el monarca Huayna Capac, provocó la guerra civil previa a la aparición hispana y causó un desastre demográfico en el Tahuantinsuyu. Finalmente Atahualpa vencería en 1532. Sin embargo su ascenso al poder coincidió con el arribo de las tropas españolas al mando de Francisco Pizarro, que capturaron al inca y luego lo ejecutaron. Con la muerte de Atahualpa en 1533 culminó el Imperio incaico. Sin embargo, varios incas rebeldes, conocidos como los «Incas de Vilcabamba», se rebelaron contra los españoles hasta 1572, cuando fue capturado y decapitado el último de ellos: Túpac Amaru I.

Los incas consideraban a su rey, el Sapa Inca, como el "hijo del sol". Muchas formas locales de adoración persistieron en el imperio, la mayoría de ellas relacionadas con las sagradas Huacas locales, pero los líderes incas alentaron el culto al sol de Inti - su dios del sol - e impusieron su soberanía por encima de otros cultos como el de Pachamama.

La economía inca ha sido descrita de manera contradictoria por los eruditos: como "feudal, esclavo, socialista (aquí uno puede elegir entre el paraíso socialista o la tiranía socialista)". El imperio Inca funcionó en gran parte sin dinero y sin mercados. En cambio, el intercambio de bienes y servicios se basó en la reciprocidad entre individuos y entre individuos, grupos y gobernantes incas. 'Impuestos' consistía en una obligación laboral de una persona para el Imperio. Los gobernantes incas (que teóricamente poseían todos los medios de producción) correspondieron al otorgar acceso a la tierra y los bienes y proporcionar alimentos y bebidas en las celebraciones de sus súbditos.

El Imperio incaico abarcó los actuales territorios correspondientes al extremo suroccidental de Colombia en la frontera, pasando por Ecuador, principalmente por Perú, el oeste de Bolivia, la mitad norte de Chile y el norte, noroeste y oeste de Argentina.

El imperio estuvo subdividido en cuatro suyos: el Chinchaysuyu (Chinchay Suyu) al norte, el Collasuyu (Qulla Suyu) al sur, el Antisuyu (Anti Suyu) al este y Contisuyu (Kunti Suyu) al oeste.

La capital del imperio fue la ciudad de Cuzco, en el actual Perú.

Импе́рия и́нков (кечуа Tawantin Suyu, Tawantinsuyu, Тауантинсу́йу) — крупнейшее по площади и численности населения индейское раннеклассовое государство в Южной Америке в XI—XVI веках. Занимало территорию от нынешнего Пасто в Колумбии до реки Мауле в Чили. Империя включала в себя полностью территории нынешних Перу, Боливии и Эквадора (за исключением части равнинных восточных районов, поросших непроходимой сельвой), частично Чили, Аргентины и Колумбии. Первым европейцем, проникшим в империю инков, был португалец Алежу Гарсия в 1525 году. В 1533 году испанские конкистадоры установили контроль над большей частью империи, а в 1572 году государство инков прекратило своё существование. Есть гипотеза, что последним независимым пристанищем инков является ненайденный город (страна) Пайтити (до середины или конца XVIII века)[1].

Археологические исследования показывают, что большое количество достижений было унаследовано инками от предшествующих цивилизаций, а также от подчинённых ими соседних народов. К моменту появления на исторической арене инков в Южной Америке существовал ряд цивилизаций: Моче (культура мочика, известная цветной керамикой и ирригационными системами), Уари (это государство явилось прообразом империи инков, хотя население говорило, по-видимому, на ином языке — аймара), Чиму (центр — город Чан-Чан, характерная керамика и архитектура), Наска (известные тем, что создали так называемые линии Наска, а также своими системами подземных водопроводов, керамикой), Пукина (цивилизация города Тиауанако с населением около 40 тысяч человек, находившаяся к востоку от озера Титикака), Чачапояс («Воины Туч», известные своей грозной крепостью Куэлап, которую ещё называют «Мачу-Пикчу севера»).

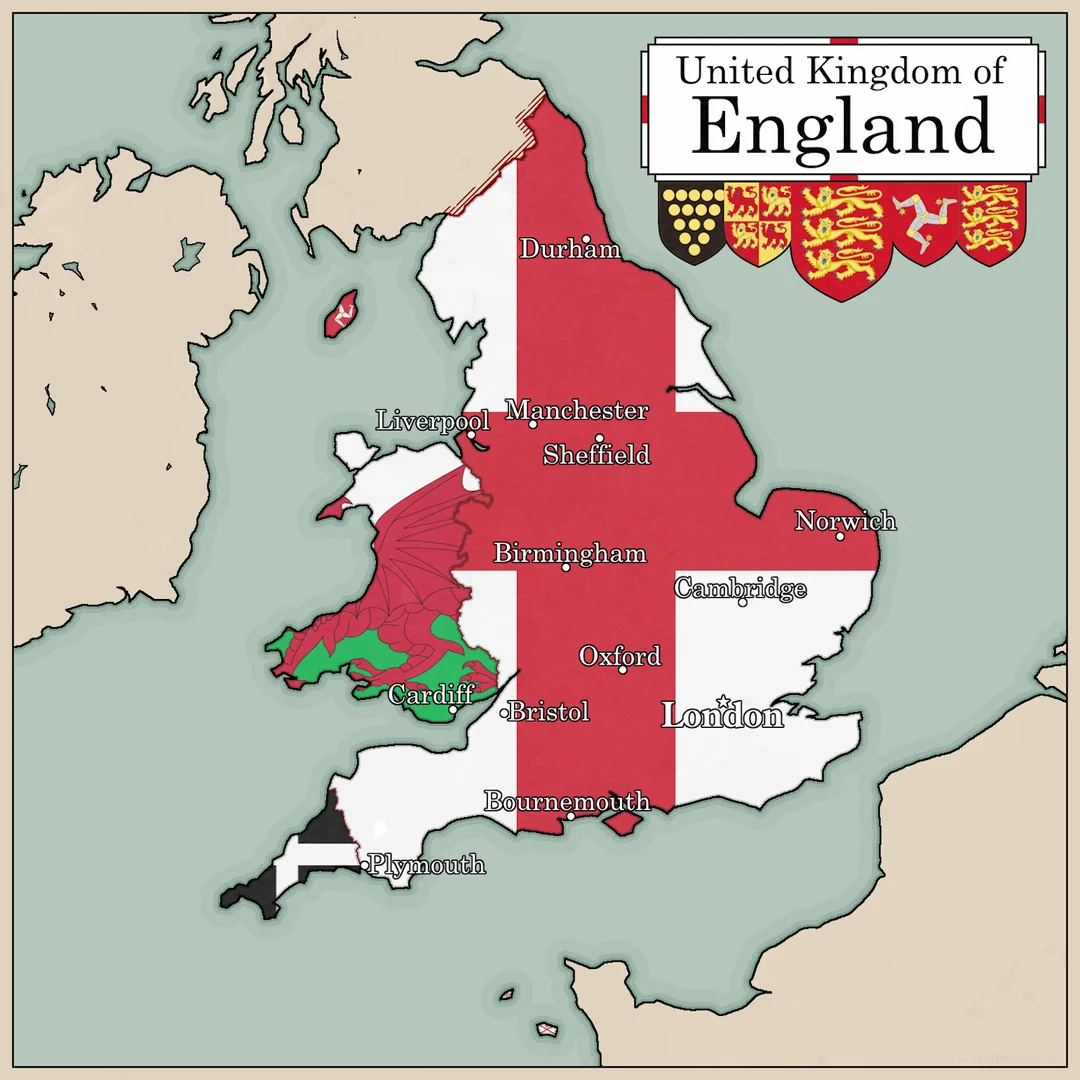

英格兰王国(英语:Kingdom of England;927年—1707年5月1日)是西欧历史上的一个国家,地处大不列颠岛南部,包含现今的英格兰与威尔士。王室的首要居所原本是汉普郡的温切斯特,但伦敦和格洛斯特被授予同样的地位——特别是伦敦,从1066年开始已经成为英格兰王国以及1707年联合法令生效以来的英国事实上的首都。

Das Königreich England bestand vom Zusammenbruch der Heptarchie im Frühmittelalter bis zum Jahr 1707. Sein Nachfolger wurde das durch den Zusammenschluss der Königreiche von England und Schottland entstandene Königreich Großbritannien.

征服者威廉或征服者纪尧姆(英文:William the Conqueror,法文:Guillaume le Conquérant,拉丁文:Willielmus Rex Anglorum,1020年代约1028年-1087年9月9日),亦称英格兰的威廉一世(英文:William I of England,法文:Guillaume Ier d’Angleterre)或诺曼底的纪尧姆二世(英文:William II of Normandy,法文:Guillaume II de Normandie),诺曼底公爵,1066年起成為英格兰的第一位诺曼人国王,直至1087年9月9日逝世。因其非婚姻出生,他的敌人称之为“杂种纪尧姆”(William the Bastard,法语:Guillaume le Bâtard)。

1066年,纪尧姆要求成为英格兰国王。他率领一支由诺曼人、布列塔尼人、佛兰芒人和法国人(来自巴黎和法兰西岛)组成的军队入侵英格兰,在黑斯廷斯战役中战胜了哈罗德二世的英国军队,随后镇压了英国人的反抗,这就是著名的诺曼征服,他也得名“征服者威廉”。

他将诺曼-法兰西文化带到英格兰,对后来的英格兰中世纪时期产生了影响。影响包括统治者的改变,对英语的改变,社会和教会的上层等级的变化,并且采用了一些大陆上教会改革的观点。影响的详细情况和程度多年来被学者争论。

Wilhelm der Eroberer (englisch William the Conqueror, französisch Guillaume le Conquérant; vor der Eroberung Englands Wilhelm der Bastard genannt; * 1027/28 in Falaise, Normandie, Frankreich; † 9. September 1087 im Kloster Saint-Gervais bei Rouen, Frankreich) war ab 1035 als Wilhelm II. Herzog der Normandie und regierte ab 1066 als Wilhelm I. das Königreich England.

Der romanisierte Normanne war der letzte Herrscher, der Großbritannien von außen erobern konnte. Das von ihm erlassene Grundbuch Domesday Book dient teilweise selbst heute noch als Rechtsquelle, vor allem ist es eine überragende Quelle für die Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte.

英格兰文艺复兴是一场文化运动和艺术运动,发生在15世纪末、16世纪和17世纪初的英格兰[1]。英格兰文艺复兴运动与始于14世纪末的意大利的欧洲大陆的文艺复兴有关。在文艺复兴开展一个多世纪后,随着北方文艺复兴运动的发展,英格兰文艺复兴才开始。16世纪下半叶的伊丽莎白时代通常被视作英格兰文艺复兴的鼎盛阶段[2]。

英格兰文艺复兴与意大利文艺复兴存在多方面不同。英格兰文艺复兴运动期间,文学和音乐作品比较引人注目。

Die englische Renaissance war eine kulturelle und künstlerische Bewegung in England im späten 15., 16. und frühen 17. Jahrhundert. Sie steht in Verbindung mit der paneuropäischen Renaissance, deren Beginn üblicherweise im Italien des späten 14. Jahrhunderts gesehen wird. Wie in den meisten anderen Teilen Nordeuropas waren diese Entwicklungen in England erst mehr als ein Jahrhundert später im Rahmen der nördlichen Renaissance zu beobachten. Der Stil und die Ideen der Renaissance drangen nur langsam nach England vor, und die elisabethanische Ära in der zweiten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts wird in der Regel als Höhepunkt der englischen Renaissance angesehen. Viele Wissenschaftler sehen ihren Beginn im frühen 16. Jahrhundert während der Regierungszeit von Heinrich VIII. Andere argumentieren, dass die Renaissance in England bereits im späten 15. Jahrhundert präsent war.

Die englische Renaissance unterscheidet sich in mehreren Punkten von der italienischen Renaissance. Die dominierenden Kunstformen der englischen Renaissance waren Literatur und Musik. Die bildende Kunst spielte in der englischen Renaissance eine weitaus geringere Rolle als in der italienischen Renaissance. Die englische Periode begann viel später als die italienische, die bereits in den 1550er Jahren oder früher in den Manierismus und Barock überging.

教宗英诺森三世(拉丁语:Innocentius PP. III;约1161年—1216年7月16日)本名塞尼伯爵罗塔里奥(Lotario dei Conti di Segni)。他于1198年1月8日当选教宗,同年2月22日即位至1216年7月16日为止。[1]他在位的时候,中世纪的圣座权威与影响到达登峰造极的状态。他声称教宗对于欧洲所有国王来说,拥有至高无上的地位。他即可毫不犹豫地开除君王的教籍。特别号召十字军东及召开四次拉特兰会议 ,成功让当时教会权势走至巅峰。同时英诺森三世完成增加教宗权力的最后工作,在其工作及改革以后,圣座的结构坚固不摇,直到十三世纪的尽头。

英诺森是第一个使用“基督的代表”(Vicar of Christ)这个名称,认为教宗这个职物有“半神”,处于人与神之间;在神之下,在人之上的说法。依诺增也自称麦基洗德,是祭司身份的君王。

Innozenz III. (geboren als Lotario dei Conti di Segni, eingedeutscht Lothar aus dem Hause der Grafen von Segni; * 22. Februar 1161 auf Kastell Gavignano; † 16. Juli 1216 bei Perugia) war von 1198 bis 1216 Papst der römisch-katholischen Kirche. Er gilt als einer der bedeutendsten Päpste des Mittelalters.

盎格鲁-撒克逊英格兰(英語:Anglo-Saxon England)是指从5世纪不列颠罗马统治的结束和盎格鲁-撒克逊诸王国的建立,到1066年诺曼征服的一段英格兰历史时期。盎格鲁-撒克逊人是对在5世纪、6世纪期间迁居不列颠群岛的日耳曼部落的总称,包括盎格鲁人、撒克逊人、弗里斯兰人和朱特人。

9世纪前的盎格鲁-撒克逊英格兰,由七个王国主导:诺森布里亚、麦西亚、东盎格利亚、埃塞克斯、肯特、萨塞克斯和威塞克斯。这些蛮族王国在7世纪完成了基督教化,而原有宗教的强势地位随着655年麦西亚国王彭达的去世而终结。

面对维京人入侵的威胁,阿尔弗雷德领导下的威塞克斯在9世纪的英格兰取得优势地位。10世纪时,各割据王国已经统一于英格兰王国,与在英格兰北部和东米德兰兹地区建立的维京人王国(即丹麦法区)相抗衡。1013年—1042年,英格兰王国被纳入丹麦王朝统治下,后威塞克斯王朝复辟。1066年最后一位无争议的盎格鲁-撒克逊国王哈罗德二世败于黑斯廷斯战役,同时标志着盎格鲁-撒克逊英格兰历史的结束。

Anglo-Saxon England was early medieval England, existing from the 5th to the 11th centuries from the end of Roman Britain until the Norman conquest in 1066. It consisted of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms until 927 when it was united as the Kingdom of England by King Æthelstan (r. 927–939). It became part of the short-lived North Sea Empire of Cnut the Great, a personal union between England, Denmark and Norway in the 11th century.

The Anglo-Saxons were the members of Germanic-speaking groups who migrated to the southern half of the island of Great Britain from nearby northwestern Europe. Anglo-Saxon history thus begins during the period of sub-Roman Britain following the end of Roman control, and traces the establishment of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the 5th and 6th centuries (conventionally identified as seven main kingdoms: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Wessex), their Christianisation during the 7th century, the threat of Viking invasions and Danish settlers, the gradual unification of England under the Wessex hegemony during the 9th and 10th centuries, and ending with the Norman conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066.

Anglo-Saxon identity survived beyond the Norman conquest,[1] came to be known as Englishry under Norman rule, and through social and cultural integration with Celts, Danes and Normans became the modern English people.

L’histoire de l'Angleterre anglo-saxonne s'étend de l'arrivée des peuples anglo-saxons dans l'ancienne province romaine de Bretagne jusqu'à la conquête normande de l'Angleterre. Elle correspond à l'histoire de l'Angleterre au haut Moyen Âge, de la fin du IVe siècle au milieu du XIe siècle.

Après les Ve et VIe siècles, généralement qualifiés d'« âge sombre », de grands royaumes anglo-saxons commencent à émerger à partir du VIe siècle et supplantent progressivement les régions occupées par les Bretons. Le plus septentrional de ces royaumes, la Northumbrie des rois Edwin (616-633), Oswald (634-642) et Oswiu (642-670), domine l'Angleterre au VIIe siècle, mais son expansion connaît un coup d'arrêt avec la défaite de Nechtansmere contre les Pictes en 685. Au VIIIe siècle, c'est la Mercie, royaume centré sur les Midlands, qui occupe une position hégémonique sous les règnes d'Æthelbald (716-757), Offa (757-796) et Cenwulf (796-821).

L'arrivée des Vikings à la fin du VIIIe siècle bouleverse la Grande-Bretagne. Les côtes de l'île sont pillées par les flottes danoises et norvégiennes avant qu'un véritable processus de colonisation ne débute dans le nord et l'est de l'Angleterre, une région appelée par la suite Danelaw. La résistance victorieuse du roi du Wessex Alfred le Grand (871-899) prépare l'unification de l'Angleterre sous l'autorité de la maison de Wessex, un processus poursuivi par son fils Édouard l'Ancien (899-924) et achevé par son petit-fils Æthelstan (924-939), souvent considéré comme le premier souverain du royaume d'Angleterre.

Les raids vikings reprennent en force à la fin du Xe siècle et aboutissent à la conquête de l'Angleterre par le Danois Knut le Grand en 1016. Son empire, qui comprend également le Danemark et la Norvège, s'effondre à sa mort, en 1035, et la maison de Wessex est rétablie sur le trône en la personne d'Édouard le Confesseur. La mort de celui-ci sans descendance, le 4 janvier 1066, sert de prétexte à la conquête normande de l'Angleterre par Guillaume le Conquérant.

La historia de la Inglaterra anglosajona cubre el periodo de la Alta Edad Media inglesa, desde el fin de la Britania romana y el establecimiento de los reinos anglosajones en el siglo V hasta la conquista normanda en 1066. Los siglos V y VI son conocidos arqueológicamente como la Britania posromana, o en historia popular como la «Edad Oscura»; desde el siglo VI, se desarrollan reinos más extensos que se denominan conjuntamente «heptarquía». La llegada de los vikingos a finales del siglo VIII trajo consigo cambios a Britania. Las relaciones con el continente eran importantes cuando desapareció la Inglaterra anglosajona, momento que se asocia tradicionalmente con la conquista normanda.

Англосаксонский период в истории Великобритании (V-XI вв.) начинается с колонизации Британских островов отдельными группами германских племен — в основном англов, саксов и ютов — и создания ими так называемых англосаксонских королевств. Его верхней границей считается Нормандское завоевание 1066 года.

《营造法式》是中国第一本详细论述建筑工程做法的官方著作。对于古建筑研究,唐宋建筑的发展,考察宋及以后的建筑形制、工程装修做法、当时的施工组织管理,具有极大的作用。此书于北宋元符三年(1100年)编成,崇宁二年(1103年)颁发施行。由将作监少监李诫所作。书中规范了各种建筑做法,详细规定了各种建筑施工设计、用料、结构、比例等方面的要求。 全书357篇,3555条。是当时建筑设计与施工经验的集合与总结,并对后世产生深远影响。原书《元祐法式》于元祐六年(1091年)编成,但因为没有规定模数制,也就是“材”的用法,而不能对构建比例、用料做出严格的规定,建筑设计、施工仍具有很大的随意性。李诫奉命重新编著,终成此书。

全书共计34卷分为5个部分:释名、各作制度、功限、料例和图样,前面还有“看样”和目录各1卷。 看样主要是说明各种以前的固定数据和做法规定及做法来由,如屋顶曲线的做法。 第一、二卷是《总释》和《总例》,对文中所出现的各种建筑物及构件的名称、条例、术语做一个规范的诠释。指出所用词汇在各个不同时期的确切叫法,以及在本书中所用名称,统一语汇。 第三卷:壕寨制度、石作制度。 第四、五卷:大木作制度:材、斗栱、昂、铺作、平坐、梁、阑额、柱、阳马、栋、柎、椽、檐、举折 第六至第十一卷小木作制度:板门,格子门,乌头门,软门, 第十二卷雕作制度、旋作制度、锯作制度、竹作制度 第十三卷:瓦作制度、泥作制度 第十四卷:彩画作制度 第十五卷:砖作、窑作制度等13个工种的制度,并说明如何按照建筑物的等级来选用材料,确定各种构件之间的比例、位置、相互关系。大木作和小木作共占8卷,其中大木作首先规定了材的用法。大木作的比例和尺寸,均以材作为基本模数。 16-25卷规定各工种在各种制度下的构件劳动定额和计算方法。 26-28卷规定各工种的用料的定额,和所应达到的质量。 29-34卷规定各工种、做法的平面图、断面图、构件详图及各种雕饰与彩画图案。

The Yingzao Fashi (Chinese: 營造法式; pinyin: yíngzàofǎshì; lit. 'Treatise on Architectural Methods or State Building Standards') is a technical treatise on architecture and craftsmanship written by the Chinese author Li Jie (李誡; 1065–1110),[1] the Directorate of Buildings and Construction during the mid Song Dynasty of China. A promising architect, he revised many older treatises on architecture from 1097 to 1100. By 1100, he had completed his own architectural work, which he presented to Emperor Zhezong of Song.[2][3] The emperor's successor, Emperor Huizong of Song, had the book published in 1103 in order to provide a unified set of architectural standards for builders, architects, and literate craftsmen as well as for the engineering agencies of the central government.[2][3][4] With his book becoming a noted success, Li Jie was promoted by Huizong as the Director of Palace Buildings.[5] Thereafter, Li became well known for his oversight in the construction of administrative offices, palace apartments, gates and gate-towers, the ancestral temple of the Song Dynasty, along with numerous Buddhist temples.[3] In 1145, a second edition of Li's book was published by Wang Huan.[4] Between 1222-1233, a third printing was published. This edition, published in Pingjiang (now Suzhou), was later handcopied into the Yongle Encyclopedia and Siku Quanshu. In addition, a number of handcopied editions were made for private libraries. One of these handcopies of the Pingjiang edition was rediscovered in 1919 and printed as facsimile in 1920.

History

History

Science and technology

Science and technology

Civilization

Civilization

Architecture

Architecture

Valle d´Aosta

Valle d´Aosta

Religion

Religion

Vacation and Travel

Vacation and Travel

Literature

Literature